The “groundwork for insurrection” in Nicaragua was laid down months and years before the coup attempt began, as our first article (3, 4) explained. But the coup could only succeed if it mobilized sufficient people into demanding that President Daniel Ortega should resign. How was this to be done, with polls showing his government had some 80% support in a country that had enjoyed several years of prosperity and social development?

One tool was old-fashioned class war. The middle and upper classes could be convinced to follow the example of the elite and of business leaders if they thought this would bring Nicaragua closer to the U.S., favor multinational investment and end the revolution, but only if there was no threat to their current prosperity. Recruiting young people from this sector, especially students in private universities, was a route to securing their support. It required constant reinforcement of the message that the protests were “peaceful,” with the violence concentrated in poorer areas while the middle classes could join in mainly peaceful anti-government marches (and they succeeded to the extent that no middle or upper-class people were killed).

However, Nicaragua’s middle class is small. The majority, poorer part of the population had been beneficiaries of a decade of government social investment. Many were firm Sandinista supporters. Turning them against the government was vital but far more difficult. Several methods were used. One was to focus the insurgency on cities like Masaya, Leon and Estelí that were linked historically to the revolution, and where young, poorer Nicaraguans could be recruited as cannon-fodder. If Monimbó, the traditionally radical barrio in Masaya, was in revolt, the rest of the country might follow.

A second tactic was to give the impression that government supporters themselves were in revolt, by branding violent opposition groups as “Sandinista mobs” and even having youths don Sandinista t-shirts before they ransacked shops.

A third was to put former Sandinista leaders like Dora Maria Téllez at the forefront, to present the opposition as a progressive alternative to the government. The money, food and weapons that they distributed in poorer areas showed that the uprising had powerful backing.

But the crucial weapon was media manipulation, at two levels. First, it was necessary to get people onto the streets, or at least to change their attitudes towards Daniel Ortega, by creating an overwhelming impression that the violence was government-provoked. This began on the first day, April 18, with fake posts on social media that students had been shot by police at Managua universities (see photos). It brought young people out ready for violence on April 19, when the first three deaths actually occurred: a police officer, a youngster involved in defending the Tipitapa town hall when it was attacked, and an innocent bystander.

Facebook and Twitter posts about fake deaths in Managua universities on April 18. The young man pictured, supposedly “shot” by police, was not a student, and died at home of natural causes. There were no coup-related deaths until the following day.

Facebook and Twitter posts about fake deaths in Managua universities on April 18. The young man pictured, supposedly “shot” by police, was not a student, and died at home of natural causes. There were no coup-related deaths until the following day.

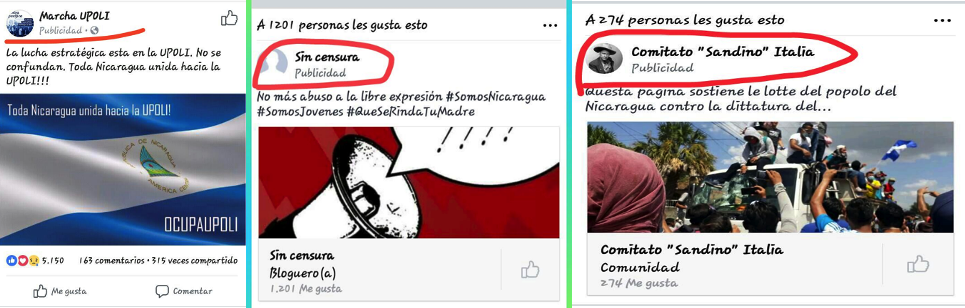

A tsunami of social media posts followed. Several reported more deaths that never happened: for example, those of Mario Alberto Medina who died months beforehand, or Marlon Josue Martinez and Marlon Jose Dávila who were both abroad at the time. In this video people give testimony of false reporting of the deaths or disappearances of sons and daughters, used to inflame public opinion. Other posts gave the impression that different solidarity organizations supported the coup attempt, including international groups, but close examination shows that these were paid publicity messages (second set of photos).

Paid-for Facebook posts (indicated by the marking “Publicidad”) giving the impression that various solidarity groups supported the coup in days following April 18 2018. Once reposted, the marking disappears.

Later, social media posts showing students “under attack” became more sophisticated and were reposted widely, including by journalists working for international media. The most notorious, viewed over five million times, showed student Dania Valeska and a young man “under fire” from police at the UNAN university, appealing to their mothers to “pardon” them for taking part in the protests, supposedly because they might die (third photo). Later, a video emerged showing students being filmed while “under fire,” clearly showing a photographer and others standing and sitting nearby, apparently indifferent to the “gunfire.” Of course, by the time it was shown to be fake, the original video had gone viral.

Paid-for Facebook posts (indicated by the marking “Publicidad”) giving the impression that various solidarity groups supported the coup in days following April 18 2018. Once reposted, the marking disappears.

The second media assault came from Nicaragua’s “independent” TV channels, websites and newspapers, most of them recipients of U.S. funding. One, La Prensa, once described by Noam Chomsky as “a propaganda journal devoted to undermining the government and supporting the attack against Nicaragua by a foreign power,” has received U.S. money since the 1980s, as William Robinson pointed out in his book, A Faustian Bargain. All these “independent” media repeated the fake stories, giving them the gloss of authenticity needed to convince local people and the international media that, indeed, a government-led massacre of students was occurring. Articles in The Guardian, El País and The New York Times then picked up the same theme, focussing on students and their “totally peaceful struggle.” Initially, the media assault was very effective: even Sandinista supporters admit that their faith was badly shaken. “We trusted our cellphones,” said one interviewed for Kovalik’s book; another recalled asking fellow Sandinistas “What about the students?”

Video posted widely on Facebook and Twitter, showing student Dania Valeska “under fire” from police, at a university roadblock.

However, as the new book Nicaragua: A History of U.S. intervention and resistance points out, “suddenly the protests were no longer peaceful, with the protesters firing mortar rounds and lobbing Molotov cocktails.” On the third day, April 20, the violence peaked. A mob of around 500, many brought in by bus, attacked the town hall in Estelí in a battle that left 18 police and 16 municipal workers injured as well as two deaths and many injuries among protesters. In Leon, an arson attack on a university killed a Sandinista supporter, Cristhian Emilio Cadena. In a sad irony, he actually was the first student victim of the protests. Media disinformation had sent society into a tailspin of protest and violence which, within just six days, claimed over 60 lives on both sides, with hundreds more injured.

Daniel Ortega acted to calm things down. He withdrew the planned pension reforms, the ostensible reason for the protests, and ordered a ceasefire by the police. He then invited the Catholic church to host a “national dialogue”, which they agreed to but then repeatedly delayed. During two weeks of relative peace, three opposition marches took place without incident. Nicaraguan researcher Enrique Hendrix told us that he believed the combination of reduced violence and the delayed start of negotiations were deliberate tactics that gave the opposition time to consolidate its forces, turn key universities into centers of criminal operations, and begin setting up roadblocks.

When the dialogue finally opened on May 16, Daniel Ortega’s opponents made it clear that their only aim was to force his resignation (the pension reforms were barely mentioned). Student leader Lesther Aleman told Ortega to his face: “This is not a table of dialogue. It is a table to negotiate your exit, as you know well. Give up!” Ortega’s reply was a further act of conciliation: ordering the police to stay in their police stations. The opposition’s response was to launch a new, bigger phase of violence, focused on the universities in Managua, but intensifying across the country as roadblocks controlled by armed rebels were erected on main roads and in many cities, taking advantage of the absence of police. Could they succeed in creating sufficient mayhem to force Daniel Ortega out of office and, even better, to leave the country?

Next month’s article will show how, as the violence increased, support for the coup began to wane.