Last month, the U.S. National Security Advisor, Jake Sullivan, outlined the international economic policy of the U.S. administration. This was a pivotal speech, because Sullivan explained what is called the New Washington Consensus on U.S. foreign policy.

The original Washington Consensus was a set of ten economic policy prescriptions considered to constitute the “standard” reform package promoted for crisis-wracked developing countries by Washington, D.C.-based institutions such as the IMF, World Bank and the U.S. Treasury. The term was first used in 1989 by English economist John Williamson. The prescriptions encompassed free-market promoting policies such as trade and finance ‘liberalisation’ and privatisation of state assets. They also entailed fiscal and monetary policies intended to minimise fiscal deficits and public spending. It was the neoclassical policy model applied to the world and imposed on poor countries by U.S. imperialism and its allied institutions. The key was ‘free trade’ without tariffs and other barriers, free flow of capital and minimal regulation—a model that specifically benefited the hegemonic position of the U.S.

But things have changed since the 1990s—in particular, the rise of China as a rival economic power globally; and the failure of the neoliberal, neoclassical international economic model to deliver economic growth and reduce inequality among nations and within nations. Particularly since the end of the Great Recession in 2009 and the Long Depression of the 2010s, the U.S. and other leading advanced capitalist economies have been stuttering. ‘Globalisation’, based on fast rising trade and capital flows, has stagnated and even reversed. Global warming has increased the risk of environmental and economic catastrophe. The threat to the hegemony of the U.S. dollar has grown. A new ‘consensus’ was needed.

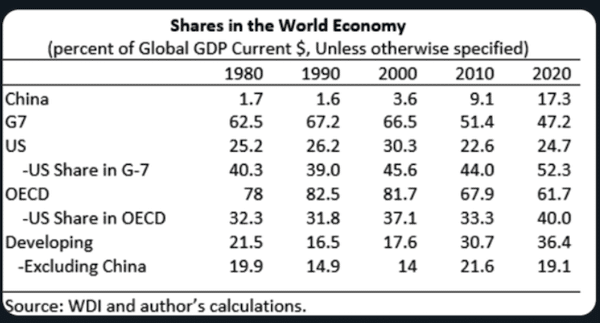

The rise of China with a government and economy not bowing to the wishes of the U.S. is a red flag for U.S. strategists. The World Bank figures below speak for themselves. The U.S. share of global GDP rose from 25% to 30% between 1980 and 2000, but in the first two decades of the 21st century it fell back to below 25%. In those two decades, China’s share rose from under 4% to over 17%—ie quadrupling. The share for other G7 countries—Japan, Italy, UK, Germany, France, Canada—fell sharply, while developing countries (excluding China) have stagnated as a share of global GDP, their share changing with commodity prices and debt crises.

The New Washington Consensus aims to sustain the hegemony of U.S. capital and its junior allies with a new approach. Sullivan: “In the face of compounding crises—economic stagnation, political polarization, and the climate emergency—a new reconstruction agenda is required.” The U.S. must sustain its hegemony, said Sullivan, but “hegemony, however, is not the ability to prevail—that’s dominance—but the willingness of others to follow (under constraint), and the capacity to set agendas.” In other words, the U.S. will set the new agenda and its junior partners will follow—an alliance of the willing. Those who don’t follow can face the consequences.

But what is this new consensus? Free trade and capital flows and no government intervention is to be replaced with an ‘industrial strategy’ where governments intervene to subsidise and tax capitalist companies so that national objectives are met. There will be more trade and capital controls, more public investment and more taxation of the rich. Underneath these themes is that, in 2020s and beyond, it will be every nation for itself—no global pacts, but regional and bilateral agreements; no free movement, but nationally controlled capital and labour. And around that, new military alliances to impose this new consensus.

This change is not new in the history of capitalism. Whenever a country becomes dominant economically on an international scale, it wants free trade and free markets for its goods and services; but when it starts to lose its relative position, it wants to change to more protectionist and nationalist solutions.

In the mid-19th century, the UK was the dominant economic power and stood for free trade and international export of its capital, while the emerging economic powers of Europe and America (after the civil war) relied on protectionist measures and ‘industrial strategy’ to build their industrial base. By the late 19th century, the UK had lost its dominance and its policy switched to protectionism. Then by 1945, after the U.S. ‘won’ WW2, the Bretton Woods- Washington consensus came into play, and it was back to ‘globalisation’ (for the US). Now it’s the US’ turn to move from free markets to government-guided protectionist strategies—but with a difference. The U.S. expects its allies to follow its path too and its enemies to be crushed as a result.

Within the New Washington Consensus is an attempt by mainstream economics to introduce what is being called ‘modern supply-side economics’ (MSSE). ‘Supply-side economics’ was a neoclassical approach put up as opposition to Keynesian economics, which argued that all that was needed for growth was the macroeconomic fiscal and monetary measures to ensure sufficient ‘aggregate demand’ in an economy and all would be well. The supply-siders disliked the implication that governments should intervene in the economy, arguing that macro-management would not work but merely ‘distort’ market forces. In this they were right, as the 1970s onwards experience showed.

The supply-side alternative was to concentrate on boosting productivity and trade, ie supply, not demand. However, the supply-siders were totally opposed to government intervention in supply as well. The market, corporations and banks could do the job of sustaining economic growth and real incomes, if left alone. That too has proved false.

So now, within the New Washington Consensus, we have ‘modern supply-side economics’. This was outlined by the current U.S. Treasury Secretary and former Federal Reserve chair, Janet Yellen in a speech to the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research. Yellen is the ultimate New Keynesian, arguing for both aggregate demand policies and supply-side measures.

Yellen explained: “the term “modern supply side economics” describes the Biden Administration’s economic growth strategy, and I’ll contrast it with Keynesian and traditional supply-side approaches.” She continued:

What we are really comparing our new approach against is traditional “supply side economics,” which also seeks to expand the economy’s potential output, but through aggressive deregulation paired with tax cuts designed to promote private capital investment.

So what’s different?

Modern supply side economics, in contrast, prioritizes labor supply, human capital, public infrastructure, R&D, and investments in a sustainable environment. These focus areas are all aimed at increasing economic growth and addressing longer-term structural problems, particularly inequality.

Yellen dismisses the old approach: “Our new approach is far more promising than the old supply side economics, which I see as having been a failed strategy for increasing growth. Significant tax cuts on capital have not achieved their promised gains. And deregulation has a similarly poor track record in general and with respect to environmental policies—especially so with respect to curbing CO2 emissions.” Indeed.

And Yellen notes what we have discussed on this blog many times.

Over the last decade, U.S. labor productivity growth averaged a mere 1.1 percent—roughly half that during the previous fifty years. This has contributed to slow growth in wages and compensation, with especially slow historical gains for workers at the bottom of the wage distribution.

Yellen directs her audience of mainstream economists to the nature of modern supply side economics. “A country’s long-term growth potential depends on the size of its labor force, the productivity of its workers, the renewability of its resources, and the stability of its political systems. Modern supply side economics seeks to spur economic growth by both boosting labor supply and raising productivity, while reducing inequality and environmental damage. Essentially, we aren’t just focused on achieving a high top-line growth number that is unsustainable—we are instead aiming for growth that is inclusive and green.” So MSSE-side economics aims to solve the fault-lines in capitalism in the 21st century.

How is this to be done? Basically, by government subsidies to industry, not by owning and controlling key supply-side sectors. As she put it: “the Biden Administration’s economic strategy embraces, rather than rejects, collaboration with the private sector through a combination of improved market-based incentives and direct spending based on empirically proven strategies. For example, a package of incentives and rebates for clean energy, electric vehicles, and decarbonization will incentivize companies to make these critical investments.” And by taxing corporations both nationally and through international agreements to stop tax-haven avoidance and other corporate tax avoidance tricks.

In my view, ‘incentives’ and ‘tax regulations’ will not deliver supply-side success any more than the neoclassical SSE version, because the existing structure of capitalist production and investment will remain broadly untouched. Modern supply-side economics looks to private investment to solve economic problems with government to ‘steer’ such investment in the right direction. But the existing structure depends on the profitability of capital. Indeed, taxing corporations and government regulation is more likely to lower profitability more than any incentives and government subsidies will raise it.

Modern supply economics and the New Washington Consensus combine both domestic and international economic policy for the major capitalist economies in an alliance of the willing. But this new economic model offers nothing to those countries facing rising debt levels and servicing costs that are driving many into default and depression.

The World Bank has reported just this week that, economic growth in the Global South outside of China will fall from 4.1% in 2022 to 2.9% in 2023. Battered by high inflation, rising interest rates and record debt levels many countries were growing poorer. Fourteen low-income countries are already at high risk of, debt distress, up from just six in 2015.

By the end of 2024, per-capita income growth in about a third of EMDEs will be lower than it was on the eve of the pandemic. In low-income countries—especially the poorest—the damage is even larger: in about one-third of these countries, per capita incomes in 2024 will remain below 2019 levels by an average of 6%.

And there is no change in the lending conditions of the IMF, the OECD or the World Bank: indebted countries are expected to impose austere fiscal measures on government spending and to privatise remaining state entities. Debt cancellation is not on the agenda of the New Washington Consensus. Moreover, as Adam Tooze put it recently that “Yellen sought to demarcate boundaries for healthy competition and co-operation, but left no doubt that national security trumps every other consideration in Washington today.” Modern supply-side economics and the New Washington Consensus are models, not for better economies and environment for the world, but for a new global strategy to sustain U.S. capitalism at home and U.S. imperialism abroad.