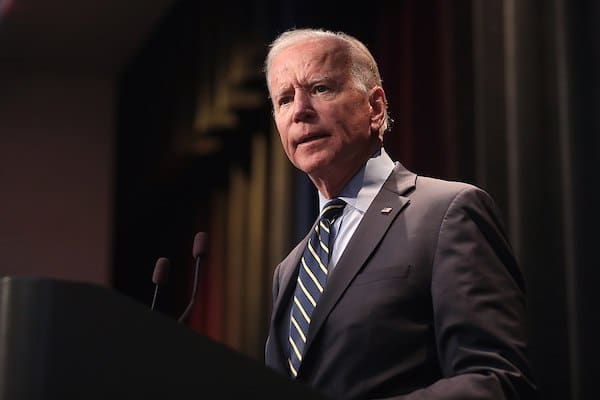

There has been a lively debate on the American left about the Biden Administration’s industrial strategy. Discussion has focused on the prospects opened up by the massive stimulus—totalling some $4 trillion, if we factor in the American Rescue Plan, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and the CHIPS and Science Act alongside the Inflation Reduction Act—from training up ‘progressive technocrats’ to retrofit buildings to the feasibility of capitalist state-led ‘decarbonization’ under conditions of global overcapacity and falling economic growth.

So far, assessments have been mixed, differentiating ‘the good, the bad, the ugly’, albeit with the stress on the first. If the boost to employment and ‘green’ good works promised by the IRA cannot be dismissed, nor can its shortcomings: lack of funding for housing and public transport, neutered regulatory standards in the electricity sector, leasing agreements that give oil and gas producers access to public land. ‘The IRA’, a representative appraisal in Jacobin reckoned, ‘is at once a massive fossil fuel industry giveaway, a historic but inadequate investment in clean energy, and our best hope for staving off planetary catastrophe’.

In other words, the left critique has gone beyond ‘good, but not big enough’—but perhaps not very far beyond. Almost entirely absent in these discussions is the geostrategic rationale that powers this national-investment drive, reshoring production on the U.S. mainland, bagging lithium mines and sponsoring construction of microchip factories, in a militarized bid to outflank China.

Viewed from the halls of power, the anti-China orientation of U.S. industrial policy is not an unfortunate by-product of the green ‘transition’, but its motivating purpose. For its conceptors, the logic governing the new era of infrastructure spending is fundamentally geopolitical; its precedent is to be sought not in the New Deal but in the military Keynesianism of the Cold War, seen by the ‘Wise Men’ who waged it as a condition for victory in America’s struggle against the Soviet Union.

Today, as after 1945, policymakers find themselves at an ‘inflexion point’. ‘History’, wrote future National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan during the 2020 presidential campaign, ‘is again knocking’:

The growing competition with China and shifts in the international political and economic order should provoke a similar instinct within the contemporary foreign-policy establishment. Today’s national security experts need to move beyond the prevailing neoliberal economic philosophy of the past forty years… The U.S. national security community is rightly beginning to insist on the investments in infrastructure, technology, innovation, and education that will determine the United States’ long-term competitiveness vis-à-vis China.

Detailed at length in a report for the Carnegie Foundation, under the signature of Sullivan and a camarilla of other Biden advisers, ‘foreign policy for the middle class’ collapsed factitious distinctions between national security and economic planning. Hopes that globalized doux commerce might permanently induce other powers to accept U.S. hegemony had been deceived. Another approach was in order. ‘There’s no longer a bright line between foreign and domestic policy’, Biden declared in his inaugural foreign policy speech. ‘Every action we take in our conduct abroad, we must take with American working families in mind.’ Trump’s victory, forged in the deindustrialized heartlands of the opioid crisis and ‘American carnage’, had shaken the Democrat establishment. What’s good for Goldman Sachs was no longer, it seemed, necessarily good for America.

Scant mystery attached to the global motivation for this break with orthodoxy. China, as Secretary of State Antony Blinken hammered home in May 2022, ‘is the only country with both the intent to reshape the international order and, increasingly, the economic, diplomatic, military and technological power to do it’. Still worse, ‘Beijing’s vision would move us away from the universal values that have sustained so much of the world’s progress over the past seventy-five years’. Happily, however, the guarantor of said values was primed to react. ‘The Biden Administration is making far-reaching investments in our core sources of national strength—starting with a modern industrial strategy to sustain and expand our economic and technological influence, make our economy and supply chains more resilient, sharpen our competitive edge.’ Competition, Blinken added, need not entail conflict. But the White House, having identified China as its ‘pacing challenge’, would not shrink from the possibility of war, beginning with ‘shifting our military investments away from platforms that were designed for the conflicts of the 20th century toward asymmetric systems that are longer-range, harder to find, easier to move’.

Three months later, passage of the Inflation Reduction and CHIPS Acts made tangible the ‘deep integration of domestic policy and foreign policy’. Restrictions on the export of crucial AI and semiconductor components to China, floated in September and certified the following month, confirmed the drive to monopolize ‘chokepoint’ or ‘stranglehold’ technologies, a veritable declaration of economic war. ‘These actions’, a CSIS analysis concluded, ‘demonstrate an unprecedented degree of U.S. government intervention to not only preserve chokepoint control but also begin a new U.S. policy of actively strangling large segments of the Chinese technology industry—strangling with an intent to kill.’ Ominously, Sullivan invoked the Manhattan Project. For too long, he maintained, the U.S. had sought only a ‘relative’ advantage in sensitive high-tech fields; it would henceforth ‘maintain as large a lead as possible’. Technology restrictions against Moscow imposed following the invasion of Ukraine were said to demonstrate that ‘export controls can be more than just a preventative tool’. Supply-chain interdiction, in defence jargon, is a key example of the fungibility of economic and strategic assets.

In Washington the music is military. Weeks before Congress voted on the IRA, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi arrived in Taipei aboard an Air Force jet, escorted by a dozen F-15s and the USS Ronald Reagan carrier strike group (‘utterly reckless, dangerous and irresponsible’ in the words of Thomas Friedman; ‘a major political provocation’ per the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs). But the augmented U.S. military threat had begun with the very start of the Biden Administration—which, far from dialling back Trump’s bluster, had built on it, only stopping to re-solder disgruntled NATO and SEATO allies to the project.

Since the revivification of the ‘Quad’ alliance at the beginning of 2021, soon bolstered by the AUKUS pact, America has enlarged its already vast archipelago of bases, invested with rapidly deployable mobile forces, deep-strike capabilities and unmanned systems. The aim, according to Ely Ratner, overseer of Asian affairs at the Department of Defense, is to establish ‘a more resilient, mobile and lethal presence in the Indo-Pacific region’. Stepped up U.S.-Japanese joint naval exercises in autumn 2022 signalled a momentous shift in Tokyo, outlined in a new National Security Strategy oriented towards the ‘unprecedented’ menace posed by China; orders for hundreds of Tomahawk cruise missiles followed suit, along with the deployment of a newly constituted Marine Littoral Regiment to Okinawa.

At the start of 2023, panic over unidentified balloon sightings coincided with the leak of a memo by the head of U.S. Air Mobility Command, whose ‘gut’ told him America would be at war with China by 2025. In February, the Pentagon announced plans to quadruple forces deployed to Taiwan, together with a surge in arms sales, and officials now publicly entertain the idea of blowing up the island’s semiconductor manufacturing facilities in the event of a Chinese invasion. Breaking openly with the longstanding diplomatic formula of ‘One China’ (claimed by both Beijing and the KMT’s Taipei, and formally acknowledged by Washington in the 1972 Shanghai Communiqué), Biden has repeatedly affirmed his intention to use force in such an eventuality. The Administration’s ditching of ‘strategic ambiguity’ was confirmed by Director of National Intelligence Avril Haines in Senate testimony this March. Periodic talk of a ‘thaw’ only underscores the tendency to escalation.

If the American left had any lingering uncertainty as to the international implications of Bidenomics it should have been dispelled by Sullivan at the end of April, in a speech on ‘Renewing American Economic Leadership’ delivered at the Brookings Institution. To those surprised the theme should be entrusted to the National Security Advisor, Sullivan again insisted on the priority of power-political concerns over Panglossian market fundamentalism. China’s rise was proof against nostalgia for globalist laissez-faire. Chinese ‘military ambitions’, ‘nonmarket economic practices’ and lack of Western ‘values’—not to speak of Beijing’s grip on lithium, cobalt and other ‘critical minerals’—demanded a firm response. Investment in electric vehicle and microchip production was a first instalment, along with the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment, an anti-China trade cartel conceived as an answer to the Belt and Road Initiative. ‘We will unapologetically pursue our industrial strategy at home’, Sullivan intoned, ‘but we are unambiguously committed to not leaving our friends behind’.

To gauge the extent of this ‘new Washington Consensus’, it sufficed to listen to Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen’s address to the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies the previous week. Yellen, reputedly the ‘dove’ to Sullivan’s ‘hawk’, opened her remarks with reference to ‘China’s decision to pivot away from market reforms toward a more state-driven approach that has undercut its neighbours and countries across the world’. ‘This has come’, she went on, ‘as China is striking a more confrontational posture toward the United States and our allies and partners—not only in the Indo-Pacific but also in Europe and other regions.’ Faced with a tense conjuncture, U.S. economic policy would obey four objectives: first, guaranteeing the ‘national security interests’ of Washington and its allies; second, continuing ‘to use our tools to disrupt and deter human rights abuses wherever they occur around the globe’; third, ‘healthy competition’ with China, contingent on the reversal of its ‘unfair economic practices’ and compliance with the ‘rules-based global economic order’; fourth, ‘cooperation on issues like climate and debt distress’. National security, global policing, competition, cooperation: the hierarchy was clear.

Rhetorically, the White House has insisted that its aim is not economic ‘decoupling’ from China, but rather ‘de-risking’—a trouvaille of Ursula von der Leyen, the so-called EU president, who musters Europeans to march to Washington’s tune. But Biden’s policies have left room for doubt concerning the fate reserved for ‘friends’ in this latest dispensation. Decades of U.S. hedging on climate goals, accompanied by hosannahs to the sanctity of free trade, found Germany and France unprepared for the whiplash return of tariffs, capital controls and national subsidies for industry. ‘Next Generation EU’, core of the ‘Green Deal’ unveiled by von der Leyen in January 2023, offers some €720 billion in grants and loans to European governments, a sum comparable to the IRA; yet as Kate Mackenzie and Tim Sahay observe, EU countries have disbursed almost as much this past year alone in subsidies to offset the energy crisis resulting from proxy war in Ukraine. Visits to Beijing by Scholz and Macron aside, the Union shows little more appetite for defying its NATO protector in Asia than it does for independent action in Europe. Josep Borrell, von der Leyen’s sidekick in Brussels, was last seen calling on member states to send warships to patrol the South China Sea.

Technology embargoes, sanctions and alliance politics all have their place in a more expansive strategic outlook, classed by Pentagon war-planners under the watchword ‘denial’. Ostensibly, these measures aim to defend American forward emplacements on China’s borders, starting with the ‘military hedgehog’ of Taiwan. That the Administration should prepare to ‘deny’ Chinese ambitions in the region enjoys broad establishment consent, from the ‘restraint’-minded Quincy Institute to the Heritage Foundation and Center for a New American Security, notwithstanding disagreement over specifics. Like containment, its proximate predecessor, ‘denial’ is a labile concept. Whereas for some, emphasis falls on its counter-position to control, or primacy—the idea that American might should be sufficiently awesome as to dispel any thought of challenging it — others, inspired by deterrence theory, draw a distinction between ‘punishment’, or threats to inflict unacceptable harm on an adversary post facto, and an activist military posture, intended to make a territory unconquerable.

Either way, Washington must reconcile the imperative to prevent any state other than itself from dominating one of the great centres of world power (Asia, Europe, the Persian Gulf) with evidence of its citizens’ likely disinclination to back a major international war abroad, after twenty years of unending armed escapades. In the thinking of Elbridge Colby, its most influential theorist, a ‘strategy of denial’ answers to both criteria, husbanding resources while laying the groundwork to mobilize public opinion. In this context, the American left’s blinkered focus on the domestic impact of Bidenomics has echoes of the ‘social imperialism’ of the European belle époque, when the Webbs and Bernsteins celebrated an increased share of the cake for their native working class, as inter-imperial rivalries and colonial depredations accelerated towards catastrophe.

Ideally, of course, Washington would prefer that the sophistication of American hardware and the strength of its ‘anti-hegemonic’ coalition in Asia dissuade Beijing from pursuing whatever designs it might have on Taiwan or the Philippines. However, as Rear Admiral Michael Studeman, director of Naval Intelligence, has warned, ‘we may be too late’. Should this be the case, the essential thing is that China be compelled to open hostilities. The relevant historical analogy is Imperial Japan in 1941, prompted by American oil embargo to launch its calamitous attack on Pearl Harbor, thereby rousing a hitherto reluctant population. ‘In circumstances where a focused denial defence would too likely fail’, Colby writes, ‘the United States’ strategic purpose should be to force China to have to do what Japan did voluntarily: to try to achieve its ambitions, China would have to behave in a way that will spur and harden the resolve of the peoples in the broader coalition to intervene and for those engaged to intensify and widen the war to a level at which they would win it.’ Plans were to be made accordingly. ‘We missed our chance to adopt a more nuanced defence strategy’, Colby has regretted, ‘and now we’re going to have to do things that appear very extreme.’

To deny is to disallow, withhold or abjure. Verleugnung, in Freudian language, has a further sense, describing inability or unwillingness to acknowledge an unpleasant or traumatic reality. It is also connected to perversion—when the desired is absent, attention may fix on a present surrogate, or fetish. The 46th President can be no stranger to such feelings. But self-deception is everywhere. When Pelosi staged her jingoistic démarche to Taiwan, Democratic apparatchiks downplayed its consequence; for Matt Duss, former foreign policy adviser to Sanders, and progressive activist Tobita Chow, the real danger was less Pelosi’s whistle-stop tour than those alarmed by it, their warnings an instance of ‘threat inflation’.

More often, denial takes the form of silence. Even thoughtful critiques—the recent Dissent symposium, ‘What’s Next for the Climate Left?’, includes a selection—barely consider the relational logic between expanded domestic spending and an increasingly aggressive Pacific policy, reiterated in speech after speech by Biden officials. That criticism also applies to the debate that NLR has been running on Dylan Riley and Robert Brenner’s ‘Seven Theses on American Politics’ (though the journal has attacked the social-imperial character of Bidenomics elsewhere). The point was registered in a contribution by economist J. W. Mason, who ventured a qualified endorsement of Biden’s spending programme that acknowledged ‘the frightening anti-China rhetoric that’s a ubiquitous part of the case for public investment’. ‘War is different from industrial policy’, Mason noted. Do America’s radicals get the distinction?

Of late, the financial press has been ahead of the eco-socialist left in starting to voice unease with the hawkishness of Biden and Sullivan. The Economist and Financial Times have distanced themselves from the Administration’s more florid flights, indicating the need to cool down gung-ho rhetoric before it makes a new reality, as Rumsfeld might have said. The FT published a strong opinion piece by Adam Tooze calling for a strategy of accommodation to China’s rise—a proposal liable to be judged ‘either treasonous or non-planetary’ by the present White House.

When Chinese authorities announced a tit-for-tat ban on the use of microchips manufactured by Boise-based Micron Technology, Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo declared that the U.S. ‘won’t tolerate’ the decision. ‘We see it as, plain and simple, economic coercion’. Coercion or prudence, ‘preserving our edge in science and technology’ or ‘modernizing the kill chain’, ‘market-distorting practices’ or support for the ‘American worker’, ‘environmental justice’ or atomic showdown over the Taiwan Strait? Critical assessments of Bidenomics ought to be sure which is which.