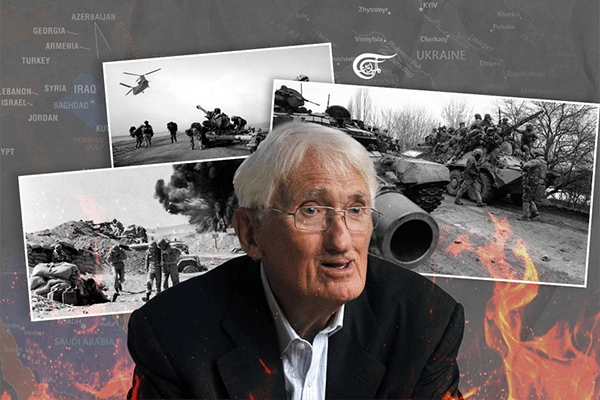

Jürgen Habermas, undoubtedly the greatest living political philosopher in Europe, has had continuous problems understanding such a crucial sociopolitical phenomenon as wars. Despite this, it is possible to observe in his thought an evolution that, despite some ambiguities, we could describe as positive. There are three milestones in this intellectual trajectory: the First Gulf War, the Iraq War, and finally the Ukrainian War.

In the first, his approach rests on the questionable premise that there are not just wars and that it would be then foolish to try to build an argument to judge the U.S. military aggression against Iraq. But once this question is ignored, the philosopher faces the difficult task of deciding if a war can be justifiable or not. And in the case of the first Gulf War, in 1991, Habermas gave the wrong answer and concluded that the war was justified. First objection: it is unacceptable to throw overboard the issue of just war, which has a long tradition in the history of Western political philosophy. Historical experience shows that the peoples who fought colonialism, Nazism, or the Vietnamese war against the first French and American aggressor or the Palestinians against the Israeli entity are just some of the examples of the just wars fought in history and this, contrary to what Habermas thinks, does not have an ounce of metaphysics. Second mistake: wondering, as the German philosopher does, whether “the victims caused by war are in a justifiable relationship to the evil that one wanted to avoid.” These evils, let us remember, were above all the preservation of the existence of the “State of Israel,” the liberation of Kuwait, the destruction of the atomic, biological, and chemical weapons that were supposedly in the possession of Saddam Hussein and, eventually, the overthrow of the Iraqi ruler. In response to his own question, Habermas disappoints his readers by saying that “I have no conclusive answer to that,” adding, however, that “worse evils than war can occur.” Which is it? He doesn’t say so, but we should then ask how many millions of Arab lives it would take for the philosopher to change his mind. Let us remember the answer that Madeleine Albright, the former U.S. Secretary of State, gave when asked if the deaths of half a million Iraqi children were “worth it”, and she responded yes. At this point, Habermas is aligned with Albright and remains ethically and analytically disarmed, turned–in spite of himself–into a contrived apologist for the new world policeman, the United States, and its Western lackeys.

In the case of the Iraq War (2003-2011), Habermas takes a different position. Perhaps his stance was a reaction to the barbaric attitude of the supposedly progressive poet and essayist Hans Magnus Enzensberger who made public his “triumphant joy” upon learning of the overthrow of Saddam Hussein’s “totalitarian regime” and lashed out at those who had warned of the disastrous consequences the attack would bring onto Baghdad. Faced with this criminal argument by Enzensberger, Habermas wrote in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung that “with this action, the U.S. has destroyed its own credibility as a guarantor of international law, the normative authority of the United States is ruined.” He continued his argument by saying that the war against Iraq was illegal on two counts: there was no situation of self-defense (the weapons of mass destruction falsely denounced by Washington did not exist at all in Iraq and there was no evidence to indicate that Hussein was responsible for the 9/11 attacks); and, secondly, because the invasion was not endorsed by the Security Council of the UN. Despite this, his mellifluous criticism of the American adventure ignored a fundamental issue: the disastrous role played by U.S. imperialism in the turbulent international scenario, far from being able to provide the normative and moral authority that Habermas wrongly attributes to it.

In the current case, the war in Ukraine, Habermas’ position is more critical, although he does not stop sinning from immoderate restraint. But in the increasingly intolerant and authoritarian political climate predominant in Germany, it was enough to publish an article in which Habermas suggested that the German government should promote the opening of negotiations with Moscow—I repeat: negotiations, not an unconditional surrender of Ukraine—for Russophobia and the spirit of the Cold War painstakingly cultivated by the corrupt NATO generals and the opulent European Union bureaucrats, and the German mainstream media and political establishment fiercely reacted by completely removing the voice of the philosopher from the “public space”; that deceitful entity that was the object of long years of Habermasian reflection. Nothing has been heard from him since mid-February, condemned to ostracism for what is apparently an unforgivable sin: his soft criticism of the warmongering that has taken over the German government and is constantly fueled by the U.S. government.

The foregoing has not been said to completely disqualify Habermas’ attitude—much more dignified than that of a good part of the European “progressive” or left-wing intelligentsia, won by a nauseating “NATOism”—but to underline that in the prevailing rarefied ideological climate that Germany and most European countries are suffering from today makes a very cautious call for prudence and negotiation (as people as dissimilar as Noam Chomsky and Henry Kissinger have also been sponsoring) a criminal offense that deserves to be punished with ostracism. The “witch hunt” and censorship practiced without anesthesia against those who oppose the war and the crazy military escalation promoted by Washington are growing day by day and claiming more and more victims. Let us remember this teaching of history: within the framework of an increasingly fascistized capitalism, all dissent becomes an unforgivable heresy.