Review of Robert Ovetz, We the Elites: Why the U.S. Constitution Serves the Few (London: Pluto Press, 2022).

People in the United States generally have confidence in the country’s political system, believing that it has the capacity to solve meaningful problems. Conservatives and liberals alike sincerely respect what they consider the nation’s sacrosanct Constitution, established following the victorious outcome of the Revolution, internal class struggles, and intense debates between Federalists and anti-Federalists. In short, the creation of it represented, in the eyes of many, a political victory. That subsequent lawmakers have added amendments to it offers proof, defenders maintain, that the Framers (delegates to the Constitutional Convention who helped draft the Constitution) created “a living document,” one that is accountable, flexible, and democratic.

Robert Ovetz’s We the Elites: Why the U.S. Constitution Serves the Few provides a necessary and forceful corrective to these popular notions, revealing that the wealthy men responsible for establishing the Constitution never wanted it to protect or promote popular democracy. This is not a new argument, but Ovetz has updated it with fascinating reflections on the myriad ways that the Framers’ creation continues to serve as a practically insurmountable barrier to our most persistent environmental, public health, and social challenges. In ten well-argued chapters, Ovetz, a prolific and gifted scholar best known for his labor studies books, echoes insights articulated by Charles Beard, the Progressive Era historian who exposed the Framers’ clear class interests in his 1913 An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States.1 Beard has few defenders in today’s academy, and his scholarship has been eclipsed by the output of subsequent generations of historians who tend to hold a far less critical view of the nation’s founding fathers.

Both institutionally based scholars and the popular presidential historians whose books adorn the shelves of big chain bookstores generally believe that the Framers were flawed but profoundly enlightened visionaries, shrewd men who were guided by more than their own narrow economic interests. Ovetz, who approaches his tasks with methodical precision, has given renewed legitimacy to the Beardian-style analysis, one that ultimately helps us better comprehend the Framers’ core intentions while acknowledging their damaging legacy. Above all, these men formed the Constitution to safeguard a capitalist economy, a system that, since its inception, has benefited the few at the expense of the many. Ovetz has produced an urgent call to action, insisting that liberals and leftists get out of their comfort zones and fully abandon their trust in the Constitution.

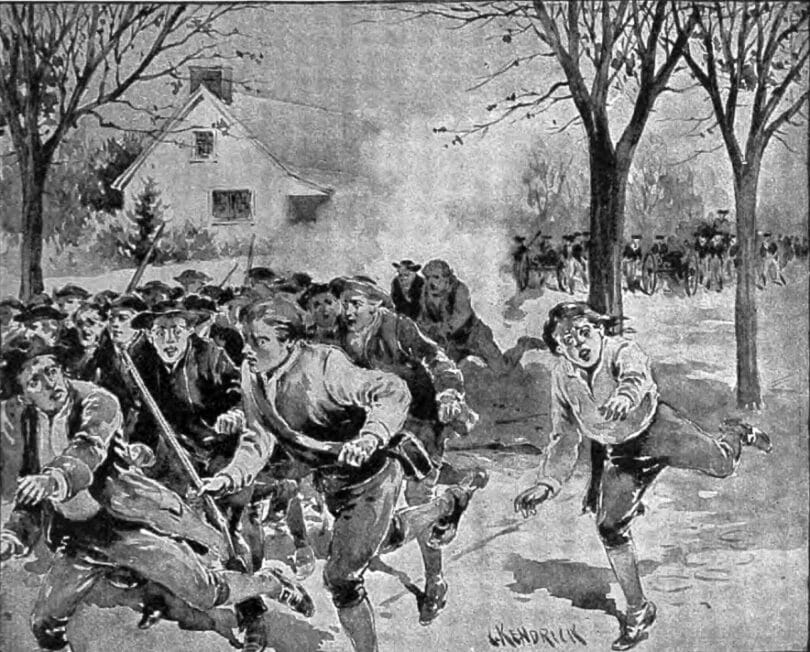

In making his case, Ovetz gives necessary context, including an exploration into the conflict-ridden atmosphere that plagued many communities after the American Revolution’s triumph. Here he investigates one of the central problems identified by Carl Becker in his 1907 study: “the question, if we may so put it, of who should rule at home.”2 The common people, the many toilers who were subject to unfair tax burdens, growing debts, and involuntary dislocations due to foreclosures, participated in a series of agrarian protests, which deeply frightened the power-hungry landowners. Ovetz gives much importance to Shays’ Rebellion, sparked in 1786 in response to excessively heavy taxes—at least four times higher that year than during British colonialism—in western Massachusetts. The elites’ feelings of overwhelming dread in the face of this conflict, Ovetz explains, “is what motivated the Framers to meet in the Convention” (42). That rebellion pit American Revolutionary veteran leaders, including those who were not present during it, against its rank and file. George Washington voiced disgust at the uprising, and another famous war hero, Samuel Adams, helped his class by authoring Massachusetts’s 1786 Riot Act, which allowed authorities to suppress the rebellion. The Framers sided squarely with the creditors.

Ovetz takes needed aim at other renowned figures from this generation. Few deserve more critical attention than James Madison, who is venerated in liberal circles. In Ovetz’s telling, the so-called Father of the Constitution comes across as excessively arrogant and almost obsessed about the ways demographic changes had the potential to harm the long-term interests of what he called the “opulent.” Ovetz refers to Madison’s famous Federalist #10 as “a classic treatise on the role of class conflict over both government and economy from an elite perspective” (32). The prolific essayist and future president followed up by producing additional pamphlets, including Federalist #51, which called for the development of policies meant to ensure “that the rights of individuals, or of the minority, will be in little danger from interested combinations of the majority” (37). Madison was explicit.

What about the document itself? Doesn’t the Constitution’s preamble, which starts with “We the People of the United States,” indicate inclusivity? Ovetz says no, and proceeds to systematically breakdown the preamble’s features, explaining that the Framers used words like “the people” to refer to themselves—wealthy, well-educated white men. Ovetz is necessarily blunt here: “The Framers did not mean the same ‘We the People’ as we do today” (43). And how did these individuals acquire their wealth in the first place? They, like others from their class, obtained it by plundering and exploiting the common people across racial lines. This involved expropriating land from Native peoples and profiting immensely from the forced labor of enslaved people and the low wages of “free” workers. The many victims of exploitation and repression had zero say over the framing of the Constitution.

Ovetz presents penetrating observations and meticulous takedowns of the different branches of the U.S. government formed by the Framers. Liberals who might start reading this book as patriotic true believers might come away from it with renewed criticisms of Congress, the executive, and the judiciary. At a minimum, they will come to recognize that representatives of all branches have, for generations, unequivocally protected property interests.

The Congressional branch, which Ovetz explores in three chapters, was “designed,” he claims, “to be inefficient when it serves the interests of the economic majority and efficient when it serves the interest of the elites” (71). Historically, it has also assisted the country’s brutalist exploiters (71). Congress, for example, had long defended the institution of slavery due to the three-fifth clause, which enhanced the power of southern states. Moreover, Congress protected the spread of slavery into the new territories acquired in the decades after the Revolution. And then there is the question of taxation. Section I.9.4 of the Constitution, Ovetz points out, was “designed with the intention of impeding or preventing the power of Congress to tax the property of elites” (95).

Ovetz offers a particularly hard-hitting analysis of the executive branch. Many of us recognize that presidents enjoy immense privileges, but Ovetz shows that these powers remain “virtually unlimited” (100). Republican and Democratic Party presidents have, for example, issued thousands of executive orders. Presidents have unilaterally deployed military forces international and domestically, declared national emergencies, and incarcerated people without due process. Moreover, they have aggressively used their veto power. Of course, Congress can override vetoes, but the record demonstrates that it has succeeded in very few cases. Taken together, the country’s presidents, ending with Donald Trump in 2020, have issued 2,584 vetoes; Congress has overturned a mere 112. Furthermore, the threshold for Congress to impeach the executive for high crimes and misdemeanors is, as Ovetz explains, “ill-defined and the supermajority vote threshold to remove is so high that impeachment has yet to be successfully used” (101). Finally, there is the matter of the electoral college, which the Framers created to undermine popular democracy. Alexander Hamilton explained its purpose in Federalist #68: to establish “effectual security against this mischief” and thus prevent “tumult and disorder” (102).

The judicial branch has played its own critical roles in preventing mischief, tumult, and disorder. Ovetz fittingly refers to it as “the last line of defense in the gauntlet of minority checks set up to protect property, and the final arbiters of elite minority rule” (128). Prior to the Constitution’s formation, the always class conscious Framers expressed disapproval of the roles of local and state judges, complaining that they were too sympathetic, and ultimately too responsive to the interests of ordinary people. Judges were popularly elected, subject to term limits, and often reluctant to punish indebted farmers. Irritated by these democratic practices, the Framers opted to establish a system in which federal judges were chosen by the president and confirmed by the Senate. They ultimately succeeded: federal courts have routinely issued decisions that protect property at the expense of ordinary people.

The court system’s practices of protecting property and capitalism were clearest in the context of the extraordinary labor struggles of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In these years, the Supreme Court repeatedly coddled union-busting employers, essentially serving, in historian Gustavus Myers words, as “the most powerful instrument of the ruling class.”3 For many decades, strikers have endured the wrath of court-ordered injunctions, preventing them from pressuring others to join picket lines and thus cutting down expressions of solidarity. In dramatic cases, including the Pullman boycott and strike of 1894, American Railway Union president Eugene Debs was arrested for violating an injunction, which he then appealed to the Supreme Court. In the In Re Debs case (1895), Justice Brewer gave the labor leader a painful lesson about the sheer force of this powerful instrument: “If the emergency arises, the army of the nation, and all its militia, are at the service of the nation, to compel obedience to its laws” (144). The Supreme Court’s actions during the so-called Progressive Era, expressed by the 1905 Lochner v. New York decision, which struck down a New York law that forbade bakers from working a ten-hour day, offers further evidence of its obvious class biases. Employers were the primary beneficiaries of these rulings.

Making changes to the Constitution remains a herculean task. Of course, we can identify several significant developments following struggles for greater racial and gender rights: the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments offered protections to African Americans and the 19th Amendment expanded suffrage rights to women. However, we have witnessed very few others over the course of more than two hundred years. The numbers speak for themselves: out of more than 11,000 attempts to add amendments, lawmakers have succeeded only 27 times. The fundamental problem stems from what Ovetz identifies as “the nearly impossible hurdle of achieving two-thirds support in both houses before proceeding to the states for three-quarters approval” (80).

After vigorously outlining the Constitution’s innumerable and practically unsolvable weaknesses, Ovetz makes sensible recommendations about moving forward. Unsurprisingly, he calls for abandoning it altogether and forming something far more accountable and democratic. Building something new, which must be generated from below while promoting and protecting “direct political and economic democracy,” Ovetz admits, will obviously be a difficult task (163). It will require convincing large numbers of fair-minded people to ditch their seemingly undying faith in the entrenched institutions empowered by the Constitution. Yet, what probably appears entirely unreasonable to many today, seemed like commonsense to Thomas Jefferson in 1789: “Every constitution then, and every law, naturally expires at the end of 19 years. If it be enforced longer, it is an act of force, and not of right” (149). Creating a fundamentally new political system that is truly accountable while upholding the rights of the actual “people” will inevitably involve a tremendous amount of organizing, discussions, and debates. But recent social movements in the era of COVID have illustrated the capacity of self-organizing and mutual aid networks. “We don’t need a constitution to tell us how to organize ourselves,” he writes at the end, “because we already do it without realizing it” (174).

We are left with serious questions. Above all, will it be possible to get this book into the hands of the many liberals who sincerely think that the threats to “our democracy” are limited to the activities of right-wing figures in and outside of official political positions? Will they read it? The urgency is obvious in our undeniably high-stakes period: global warming, increased labor strife, grave public health emergencies, persistent official and covert U.S. military interventions, institutional racism, gender oppression, attacks on queer and trans people, and the increasing widening economic gap between ordinary people and elites. These stubborn ills have plagued us under political leaders represented by both mainstream parties. By reading this book, we can hope that fair-minded liberals, those who bristle at the activities of today’s conservative judges and policymakers, shake their heads in disgust at the January 6, 2021, attempted insurrection, and shudder at the thought of a dystopian Trumpian future, will come to realize that our most pressing problems are structural rather than partisan. Then we will begin to make progress.

Notes

1. Charles A. Beard, An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States (New York: Macmillan, 1913).

2. Carl Lotus Becker, “The History of Political Parties in the Province of New York, 1760–1776” (PhD dissertation, University of Wisconsin, 1907), 22.

3. Gustavus Myers, “Prospectus of History of the Supreme Court of the U.S.,” Montana News, July 27, 1911, 2.