Two previous articles (1, 2), (4) described the build up to the attempted coup in Nicaragua and how the media were crucial in convincing the public to support it. This article, covering the period from May 30 onwards, shows how the initial support peaked, then collapsed.

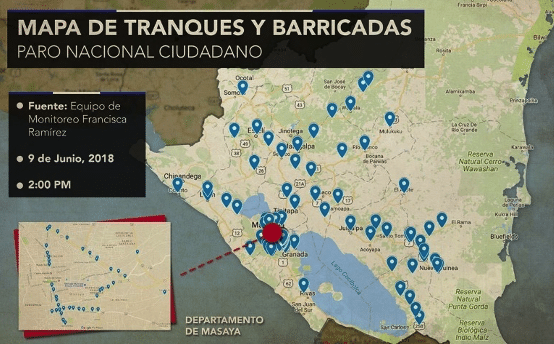

After more than a month of conflict, most Nicaraguans hoped that a “national dialogue” set up by the Catholic church would lead to peace, but in fact it led to renewed violence. During the hiatus before the dialogue began, and with the police now confined to their police stations on Daniel Ortega’s orders, roadblocks were set up on all the country’s arterial roads and throughout many key cities (see the map published by one of the coup leaders). Quickly dubbed los tranques de la muerte (“death roadblocks”), they not only strangled the country’s transport system but became the scene of intimidation, robberies, rape, kidnappings and murder.

Map of roadblocks in Nicaragua in June 2018, published by coup leader Francisca Ramirez.

The limited public support for the coup reached a climax at the so-called “Mothers’ Day march” on May 30, 2018. Two huge demonstrations took place in Managua, one in support of the government and a bigger one supporting the coup. The day began and ended with violence. Sandinistas travelling to the march from Estelí were ambushed at the roadblock to the south of the city: 27 people were shot, three dying from their wounds. In total, 28 people would die in that one day, of whom seven were Sandinistas, eight were opposition protesters and the rest of unknown affiliation or bystanders.

Armed roadblock operators south of Estelí, several with conventional weapons, others with “homemade” mortars.

Most of the deaths in the capital occurred because groups of protesters tried to cross police lines to attack the rival Sandinista march. Roadblocks were set up near the national stadium, from which protesters confronted the police. Some were filmed carrying firearms and even apparently shooting at fellow protesters, as seen in this documentary by Juventud Presidente (a pro-Sandinista media group). Other, peaceful protesters leaving the large march were caught in crossfire: allegedly this came from police sharpshooters, but may well have been a “false flag” operation to create chaos, because 20 police officers received firearms injuries. Later, some of the incidents were “forensically” examined by a “group of experts” commissioned by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR). A special website was created to show the evidence gathered, which focused solely on deaths among the opposition, as did a wider report on casualties by the same “expert” group. In response, an open letter was sent to the IACHR’s parent body by dozens of activists and solidarity organizations, pointing to the startling inaccuracies and omissions in the reports. Possibly as a result of the letter and accompanying article, a video reconstruction of the fatal incidents posted on the special website, was later taken down.

For the U.S. government, corporate media and international human rights bodies, the “Mothers’ Day march” became emblematic of the protests. The opposition still laud the march as a triumph but afterwards it could be seen as marking the peak of their support. This was because in the weeks after May 30 the violence intensified: even the biased reports from local “human rights” groups show that for the whole of June, the majority of victims were ordinary people or Sandinista supporters. A family house in Managua’s Carlos Marx neighborhood was destroyed by fire: six people were burnt alive, including a baby and a two year-old girl. Arson attacks were launched against the pro-Sandinista Radio Ya, the old colonial town hall in the tourist city of Granada and the main secondary school in the city Masaya, serving over 3,000 pupils. Many other public buildings and homes of government supporters were destroyed. The opposition tried to blame all these incidents on Sandinista mobs, with opposition media such as 100%Noticias often having reporters present immediately an attack took place, so as to grab the headlines.

But for several violent incidents, it was more difficult to twist the story. On June 13, student leader Leonel Morales, who had urged fellow students not to support the protests, was kidnapped, shot and left for dead. On June 12, the municipal depot in Masaya was destroyed, together with all the vehicles used to maintain the city streets; those guarding the plant were kidnapped, culminating in the disabling torture of Reynaldo Urbina (who is known to both of us). Both the Catholic church and one of the Nicaraguan “human rights” bodies collaborated with the kidnappers.

On June 19, while the police station in Jinotepe was under siege, protesters brought two stolen fuel tankers close to the building and tried to explode them. On June 21, a young, gay Sandinista, Sander Bonilla, was kidnapped and tortured in Leon by the opposition in the presence of a Catholic priest.

On July 12, a supposedly peaceful procession of vehicles driven by opposition supporters entered the small town of Morrito and launched a fusillade of gunfire at the police station, killing five people. Local media portrayed the incident as a “confusing exchange of fire” in which a protester had been killed. A widely used photo showing the victim was false, however: it had been taken in Honduras in 2009.

Protester “killed” in the attack in Morrito on July 12: the photo is actually from Honduras, taken several years earlier.

Perhaps the saddest incident occurred in Masaya on July 14-15. Young, unarmed, off-duty police officer Gabriel de Jesús Vado Ruíz was kidnapped, tortured and, on the second day, killed. A Catholic priest, Harvin Padilla, was recorded telling the culprits that videos should not be posted because of the bad image they would create. Another priest, Edwin Roman, together with human rights worker Alvaro Leiva of local “human rights” body ANPDH, then attempted to remove the corpse and hide the crime.

Gabriel Vado’s body burns next to a roadblock in Masaya, July 15 2018.

Of course, the accepted history of the coup attempt, as told by the U.S. government, international bodies such as the UN Human Rights Council and most of the media, is that nearly all the victims were protesters, mainly students, killed by police or by Sandinista “paramilitaries”. The truth is far more complicated; people on the ground, especially those living in the places most affected, became increasingly aware of the opposition’s intentions. As Idania Castillo, a Sandinista quoted in Dan Kovalik’s book, Nicaragua: A History of U.S. intervention and resistance, points out: “the goal of the insurrectionists… was not just to depose the government, but to destroy all vestiges and historical memory of Sandinismo itself.” In a recent conversation, a friend who lived through the worst of the violence in Masaya, and survived an attempt to kill him when armed protesters burst into his home, described how, at nighttime, Sandinistas identified at roadblocks were stripped and painted blue and white (the colors of Nicaragua’s flag) before being forced to flee naked; neighbors would meet them with towels and water to help them.

By late June and early July 2018, patience with the insurrection had evaporated and most Nicaraguans simply wanted a return to the peace and stability that existed beforehand. Even those who were not government supporters, including many who initially joined the protests, could see where they were leading. They had experienced the benefits of a Sandinista government and (if they were old enough) the previous attempt to overthrow it violently, in the 1980s. Social progress was under threat and conflict was intensifying. It was time for three months of mayhem to come to an end.

The final article will explain how the coup attempt was halted, discuss its aftermath and consider what it means for the future of Nicaragua’s revolution.