When you bite into nature,

nature bites back,

it’s just the ways that it is,

a matter of fact—Peter Wilde, “People in Trees”

“Welcome to our fabulous clear-cuts,” my friend Tyranny said to me, gesturing out the car window to the bare, scrubby hillsides denuded of their former pine trees. We were driving through the Oregon forests—or what remained of them—between Eugene and Corvallis, just south of the Alsea Falls. There are many such clear-cuts throughout Oregon, large tracts often logged at obvious 90 degree angles, standing in sharp contrast to the trees around them. From far away, seen along the highway, the clear-cuts look ridiculous, funny even. The closer you get to them, the uglier the scars become. Many of the state’s ancient old-growth forests have largely succumbed to logging and fires. The fight to stop the clear-cutting has taken many forms over the years, and some activists have taken truly desperate measures to stop them.

The U.S. Pacific Northwest has a very bitter history amongst the logging industry, environmentalists, labor, the state, and law enforcement. “Tyranny,” their forest name, a moniker that many forest defenders go by in order to avoid identification with their legal names, knows this troubled history well. Going back to the 1990s, Tyranny has been involved with many disruptive actions targeting the logging industry in efforts to protect the environment. These were the days when activists would lock their arms beneath the asphalt of logging roads in contraptions called “dragon slayers,” or build large fortifications blocking traffic. There were the tunnel diggers who burrowed beneath forest access roads such that they would collapse if heavy equipment drove over them. Large tripod structures were built for activists to camp in. And of course there were the tree sitters, camping in trees for days or weeks at a time. Some climbers would string lines between multiple trees so they could travel between them. “The idea is to make it so that if they cut the tree down they kill you,” Tyranny said. It’s dangerous work. In 2002, a woman named “Horehound” fell and died at a tree-sit defending Eagle Creek near Portland. Women were doing a lot of this dangerous work, as well as much of the support work of supplying tools, food, and water. “A lot of the guys were just getting high and hanging out on the ground,” Tyranny said.

Days before our drive through the woods, Tyranny and I had been walking the streets of Eugene, a center of the anarchist-style radical environmentalism throughout the 1990s, and a good place for dumpster diving, they told me. We saw posters plastered on walls and telephone poles decrying the recent police killing of Tortuguita in Atlanta, Georgia. Tortuguita was a young forest defender involved in actions to stop “Cop City,” a new police training facility currently under construction in the Weelaunee forest outside Atlanta. During a police sweep of the forest to remove occupiers, Tortuguita was murdered in the forest in a hail of police bullets, with an autopsy indicating they had their hands raised and was sitting cross-legged. Graduating magna cum laude from Florida State University, Tortuguita “had been active in Food Not Bombs, helping feed homeless people in Tallahassee, Florida,” writes PBS. The posters in Eugene, bearing a picture of Tortuguita smiling in the forest, called for worldwide solidarity with the Stop Cop City movement.

“The cops say he had a gun,” Tyranny remarked.

But you can’t trust what they say. They lie.

This was January 2023. At this time, the Weelaunee Forest was a home for many forest defenders and other activists trying to stop construction of the police training center. Community breakfasts were taking place in the forest every Wednesday morning. People were living in trees and camping in tents. Though under threat, the eighty-five acres of forested area where the training center would be built was still there, alive. But soon, the movement in Atlanta would face a harsh, devastating reality that environmentalists in Oregon had learned a long time ago. Something called chainsaw justice.

~

On September 7, 2023, I joined a student-organized march in Atlanta in support of Justice for Johnny Hollman. The marchers met first at the campus of Clark Atlanta University, a historically Black university known for its central role in student organizing to desegregate Atlanta in the early 1960s. Members of Hollman’s family were present, sporting white t-shirts reading “Justice for Johnny Hollman.” The family thanked the marchers for their support and asked that as many of them as possible join the family the next day for when they would hopefully see the police bodycam footage of the killing of their father, grandfather, brother, husband. Mr. Hollman, a 62-year-old deacon at Lively Stones of God Missionary Baptist Church and grandfather of twenty-six grandchildren, was killed by an Atlanta police officer after the officer tased Hollman for not signing a traffic citation. Deacon Hollman called the police himself after the traffic incident.

The marchers, a group of about fifty of us, some pulling ice chests full of bottled water, some riding in their cars alongside those who walked, made our way from the Clark Atlanta University campus, chanting classic chants and singing songs, and gathered at the CNN offices in downtown Atlanta. With the call and response chant of “Say His Name!” I had to stop myself multiple times from saying “George Floyd.” It was the first natural response after saying it for so long.

Before the march got going, as I was driving to the college, I passed the CNN building and saw a good number of police vehicles parked in front of it including a couple “prisoner transports,” a bureaucratic term for paddy wagons. Perhaps after seeing our relatively low numbers and that we were sticking to the sidewalk, most of the police left CNN before we even got there, leaving only a couple vehicles and three or four officers.

Once at CNN, a few speakers got on the megaphone, starting with a student named Malik who sported a t-shirt with a picture of the Black Panthers on it and the caption “Home Land Security, Fighting Terrorism since 1966.” In his speech, which he said he prepared ahead of time so that he didn’t just ramble and “cuss for 10 minutes,” he tied Hollman’s killing to a bipartisan system that is intent on building Cop City in response to the 2020 George Floyd uprisings. He said the rulers of Georgia are scared.

“Andre [Dickens, Democratic mayor of Atlanta and supporter of Cop City] came to the AUC, to Clark, Spellman, Morehouse, Morris Brown, and the ITC, begging, begging for the stamp of approval. For Black America’s future leaders. For the Black middle-class. And we denied him,” Malik said, referring to the mayor visiting local Black colleges to garner support for Cop City. “Hoping, he was hoping to avoid yet another student uprising like in the 1960s and ’70s that started here in Atlanta, because he fears the power that another uprising could have.” He went on:

We know who the enemy is. And we have to be clear about it. This family and this city are not suffering because of a couple bad eggs. They are suffering because of a system. And it’s not a broken system. It’s a corrupt system. There is a difference. It is working just fine, it’s worked perfectly fine for the last 500 years. Not just against us Africans, but against our indigenous brothers and sisters, the working class everywhere, all over the world! The boot heel of white supremacist capitalism has laid its hands on our people. Across all seven continents, imperialism has run amok. This is nothing more than imperialism at home. These people are not here to protect you, they are an occupying force. And they routinely kill people on purpose because it instills fear. It instills fear. What do you call it when someone commits an act of violence in order to instill fear? Terrorism! You call that terrorism, don’t you? Isn’t it ironic how they call us the very thing they are?

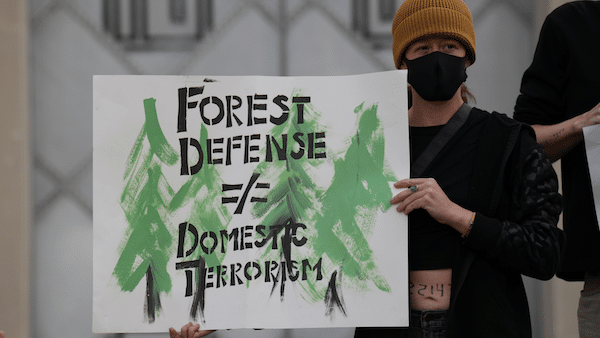

He was referring to the over forty activists who were arrested in the Weelaunee forest and charged with domestic terrorism offenses. Two days before this march for Hollman, all of those previously arrested on terror charges, as well as others, were indicted on Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO) charges, a charge designed to bring down criminal organizations such as the mob by tying all of its members to a criminal conspiracy regardless of the severity of individual offenses. Some of those indicted were previously arrested at gunpoint for running a bail fund for imprisoned activists, a longtime mutual aid tactic of civil rights movements. Others were arrested for nothing more than posting flyers identifying a cop involved in Tortuguita’s murder. On the very morning of the march for Hollman, five activists staged a work stoppage at the forest construction site by chaining themselves to a construction vehicle and livestreaming their motivations. All five were shortly arrested.

Malik closed his speech with the call and response chant made famous by Black Panther chairman Fred Hampton (Malik being about the same age as Hampton), always seeming more real from Hampton’s lips than from any other’s:

I am! / I am! / a revolutionary! / a revolutionary!

Another speaker got up and lamented the fact that we had to be there that day, that students shouldn’t have to be leaving their schools to decry yet another police killing. He became visibly verklempt as he talked and the crowd cheered him through it. A woman got up and sang “A Change’s Gonna Come.” Another man came up and tied the movement to defend the Weelaunee forest to efforts throughout the South’s history at protecting indigenous land, and how the Black community has often failed to stand up with their indigenous brothers and sisters. The powers that be have stolen the land, he said, we’ve been forced out, gentrified out, “at some point in time, ain’t nowhere else to run.”

Another women spoke of the need to step up the pressure against the existing power structure.

We can’t just be in the AUC and chillin’…if it don’t mean nothing. We have to be revolutionary.

At the end of the speeches, we all gathered in a circle and linked arms. A professor from the college affirmed the solidarity of our march that day, spoke of the importance of a youth-led movement, and reminded people to be there for the Hollman family the next day after they watched the bodycam footage.

Walking back to our cars, one of the marchers told me that a vigil would be happening that night at the Dekalb County Jail in Decatur for the five people arrested at the construction site that morning. I told them I would be there. We chatted about the destruction of the forest. “It hurts. It’s so horrible seeing it,” they said. They told me people used to gather in the forest. It was a community spot. And now the police and the government have taken that away. They pushed everyone out. The Wednesday food distributions are still happening, but outside of the construction zone now. Shortly after the mass arrests and domestic terror charges were handed down, with the forest effectively deprived of defenders, the clear-cutting began. When you drive by the site now, you can see it’s totally blasted. It’s worse than the clear-cuts in Oregon. The land has been totally uprooted and prepared for the concrete pouring. With police terror gaining the upper-hand in the forest, the movement shifted chiefly from forest defense to the monumental effort of organizing a public referendum, gathering enough signatures to put the training center up for a vote. And thus with no physical resistance ongoing at the site, the forest zone has been decimated. It’s gone. The backhoes continue apace. Police guard the perimeter fence. This is chainsaw justice.

At eighty-five acres and a $90 million price tag, the future training center is a massive blight on the forest and a drain on the community. The proposed building includes a gun range, a mock city for police training—similar to mock villages that the military uses for combat training—a burn building for the fire department, and a horse pasture. The Atlanta Police Foundation, an organization that receives generous funding from many corporations, states that Cop City will catapult “APD and Atlanta Fire Rescue to the vanguard of major urban law enforcement agencies,” and that it “will emphasize cultural awareness, community knowledge, and the variety of citizen concerns that modern policing in a diverse city requires of an effective and trusted law enforcement agency.” In a city known as being a “Black mecca,” Atlanta City Council’s decision to give over public land to the building of a state-of-the-art police training facility, in the face of overwhelming negative public comment and shortly after the 2020 uprisings against police brutality, is a sharp sting to many of those in the movement. My forest defender friend named Moss, another “old-timer” in the Oregon movement like Tyranny, called Cop City “the World Trade Organization of cops.”

When I told Moss the names of the various groups fighting Cop City—Stop Cop City, Defend the Atlanta Forest, Save Weelanuee, etc.—they said that the focus should be shifted slightly, more on the positive aspects of the forest and the beauty of humanity and less on the cops. “I learned to keep the vision about the life and not the destruction. There was a way that you could talk and kind of feel the spirit of everyone lift and get stronger. Talking about the destruction, you could feel that energy in your chest dissipate.” They suggested “Long Live Weelaunee” as a campaign name. This is beautiful, I suppose. But it is also somewhat indicative of the kind of soft, touchy-feely language employed by hippies in the environmental movement that I find to be so saccharine and worthy of eye-rolls. I’m on their side. But damn I just want to slap them in the face sometimes. Moss is certainly not a pushover though. They’ve been arrested more times than they can count for defending the ancient forests of Oregon. In the wake of 9/11, they were stalked by federal agents and given a grand jury summons as a way to gather information on what the state (and corporate America) had defined as an “ecoterrorist” movement.

The momentum of the most radical wing of the environmental movement was effectively destroyed by harsh sentences imposed on Earth Liberation Front members post 9/11. The movement to Stop Cop City is now suffering the same tactics of state repression with the demonizing of protesters as domestic terrorists and painting the entire movement as criminal. Though the fight continues, it can feel like a full-time job for some.

“We’ve been good about avoiding burnout,” one person at the Johnny Hollman march told me. People have been taking care of each other and prioritizing rest when needed, they said. Exhaustion is always a problem with frontline movements. “It’s a young person’s game,” Tyranny said to me. When it comes to defending the trees, there is a tendency to feel like you’re never doing enough. “Being on the front lines drains you,” Tyranny said. “We tied up our self-esteem with our actions. There’s this attitude of: ‘What have you done for the earth lately?’ Being on the front lines for years, people get burned out. And then they find that they’ve bound their self-worth with always being a part of the action. They need to find a way to reorient themselves.” The importance of “self-care” and mutual aid have a lot of prominence in the movement in Atlanta today. Of course, burnout in the face of police terror is a real and serious thing. But with trees being cut every day, lost forever, how the movement overcomes the problem of burnout to maintain consistent resistance is an essential question.

Later that night when I got to the Dekalb County jail in Decatur, around twenty people were standing on the sidewalk outside the building, candles and signs in hand. One person led everyone in a song, “Divisionary (Do The Right Thing)” by Ages and Ages, a relatively new song that seems to have become a staple in the movement. Two women Unitarian reverends were present and speaking to reporters. Two of the prisoners arrested that morning were fellow clergy members. One of the reverends outside the jail spent hours trying to visit the prisoners but was not allowed inside the building. Also present was Rabbi Mike of the local Bet Haverim synagogue. The rabbi said that he tried to bail out one of the prisoners but was told that they had not even seen a judge that day, no bond had been set, and they probably would not get out until at least the next day. The Bet Haverim synagogue is a liberal, reformist-style synagogue founded by gay and lesbian Jews. One person at the vigil told me they moved to Atlanta partially because Bet Haverim was one of the few “gay synagogues” in the country.

One of the prisoners, Ayeola, called and said they were being denied their medication. A few people discussed starting a campaign on social media for people to call the prison demanding that their medication be supplied. According to one person, the prisoners were being charged with trespassing and obstructing an officer, but thankfully no terrorism charges. “We’ll see,” I said. Not to be a downer, but the state can throw whatever they want at you whenever they want. It wasn’t until over two years after Jessica Rezinek and Ruby Montoya were arrested for damaging oil pipelines that they were given domestic terrorism enhancements. The prisoners have since been released without having to pay bail and were given do-not-return orders for the construction site.

As the night went on and people at the vigil grew tired, the numbers slowly started to dwindle. Some people had already been at a rally that morning at the construction zone in support of the occupiers. Talking with one of the remaining attendees, they again tied the building of Cop City and the suppression of forest defenders directly to Atlanta’s fear over another uprising like 2020. They referenced “the Atlanta Way,” the liberal notion that the city’s Black (mis)leadership class and its white upper-class business interests largely work together and are in agreement on race relations. They talked about the public-private partnerships that have defined Atlanta and indeed much of the neoliberal era. During the 2020 uprisings, Atlanta saw what some considered to be unprecedented property destruction and violence. “They’re scared that the Olympics won’t come back,” they said. 2020 refuted the liberal Atlanta Way of capital investment taking precedence over questions about the color line. Now, instead of dealing with underlying racial and economic issues, the city is resorting to repression and increased policing. “They don’t want another uprising.” That’s what Cop City represents.

In response to the perhaps undeserved reputation Atlanta has as “the city too busy to hate,” that Atlanta is somehow separate from the rest of the South, James Baldwin wrote “Atlanta, however, is the South. It is the South in this respect, that it has a very bitter interracial history. This is written in the faces of the people and one feels it in the air. It was on the outskirts of Atlanta that I first felt how the Southern landscape—the trees, the silence, the liquid heat, and the fact that one always seems to be travelling great distances—seems designed for violence, seems almost to demand it.”

I can’t say that I’ve seen this bitter history written on the faces, mostly of Black people, that I see here today, these fifty years later. But Atlanta is not exactly a kind city. One rich white guy in Inman Park with a Ring camera on his front door and who made sure I knew he was part of an HOA threatened to call the cops on me because I parked in front of his house one too many times. I also overheard one snooty rich white woman living in Inman Park telling her visiting friend over the phone to avoid the Little Five Points area, a neighborhood that is decidedly more warm, welcoming, and grungy than Inman Park, and which was the site of a 1906 massacre of some twenty-five Black people at the hands of white rioters. I spent most of a night hanging out on the communal benches at the center of Five Points with a group of crusty train hoppers. We played music and talked books and politics while they got crossed with a mixture of beer, weed, rolled cigarettes, and canisters of nitrous oxide they purchased down the street labeled “do not inhale.” They were friendly and giving to whoever came by, offering a smoke or a few bucks to those in need. Other people came by and gave us fresh veggies from their garden and leftovers from the restaurant they work at. One drunkard was lifted from the ground and placed upright on a bench by fellow homeless denizens. Fat chance finding any of this kind of camaraderie in Inman Park. The first thing they do there is call the cops on you.

And Atlanta is an extraordinarily unequal city, with its mostly Black Eastern neighborhoods where Cop City is being built standing in sharp contrast to the white wealth of suburbs like Dunwoody, a place that I slept in my car for a night and woke up to a white polo-shirted father peering in my window. And Atlanta is indeed a hot city, with this year having seen multiple triple-digit heat waves. And for someone who sleeps outside, the humidity can be simply unbearable. High temperatures certainly do make the blood boil. On the day that Tortuguita was murdered, the high was 85 degrees, though certainly cooler in the forest. Warm for January. But hardly violence worthy.

Trotted out by apologists for Cop City is the usual criticism of “outside agitators” coming and stirring up trouble against the wishes of the community. It is important here to have some nuance and make some distinctions. It is one thing for masked black bloc anarchists to come into a community and break windows and throw Molotov cocktails at cop cars without any regard for what local organizers in the movement want. After this kind of property destruction happened at the construction site in March of this year, Bernice King, daughter of Martin Luther King Jr., and the King Center began to distance themselves from the movement, one activist told me. “Black people don’t like seeing Molotov cocktails being thrown around,” they said, “People threw bombs into Martin Luther King’s house.”

Coming into someone else’s community as an activist must bring with it a sense of humility and a commitment to listening first and acting second. I can tell you that I heard a leading organizer at one of these events say that they’ve “never really been concerned with legality,” and that they “think it’s time to learn from our ‘eco-terrorist’ brothers and sisters.” Another person who was born and raised in Atlanta said they haven’t been involved with the referendum campaign because they don’t do electoral politics and instead focus on mutual aid, a notion that was explicitly cited in the RICO indictments as evidence of anarchistic criminality.

In a recent online meeting with Cornel West organized by Georgia Conservation Voters in response to the RICO indictments, Dr. West emphasized the importance of solidarity and “universality” in movements for justice, and that this keeps alive the legacies of Martin Luther King Jr. and Fannie Lou Hamer:

It means that we have to straighten our backs up and take a stand in the name of solidarity.… I’m not one to use the word “allies.” That’s not my language, at all. Bill Evans playing the piano for Miles [Davis] Quartet, he’s a vanilla brother, he’s a white brother, he ain’t no “ally” in the band, he’s in the mother ‘uckin’ band. And the question is we all got to be in the band. Like Gregory playing the drums for Sly and the Family Stone. He’s a white brother. He ain’t a white “ally” in the band, he’s in the mother ‘uckin’ band. And the question is we either choose to be in the band or we choose to be spectators. No matter what color you are. It’s a human choice of integrity, honesty, decency, courage. And that’s precisely what this movement has been, and is, and will continue to be.

Of course every movement, especially non-hierarchical ones, will have differences of opinion on tactics. Of course, as an outsider deliberating questions of property destruction, it is best to defer to community leaders. But those who a priori decry activists from outside of Georgia coming in to help stop Cop City seem to be unlearned on the concepts of solidarity and comradeship. The timber wars of the Pacific Northwest saw many environmentalists from around the world join in the struggle because a threat to the environment anywhere is a threat to the environment everywhere. Wisened tree sitters have important skills to share. The Civil Rights movement saw many people from the North come down to help organize during the 1964 Freedom Summer. Some of these “outside agitators” were murdered by the KKK. Leftwing movements have always had an internationalist tendency because they recognize that their struggles against capitalism are interconnected. The Vietnamese war for liberation was boosted immensely by Chinese and Soviet arms as well as much leftwing sympathy throughout the West. The Spanish Civil War was lost to fascism because the Republic and the scrappy international brigades could not get modern weaponry from any of their formerly allied capitalist nations, relying only on antiquated supplies from Russia. Wherever sparks are flying, there the left must be in solidarity. We fight and suffer and rise and fall together.

One activist who attended the meeting with Cornel West revealed that there were plans in the works for mass civil disobedience actions to happen sometime in November. Since the meeting, a new group called Block Cop City has confirmed that it is organizing a nationwide campaign to culminate in the occupation of the construction site on November 13, writing “The people will have to enforce their own stop work order. This is the only way to honor the overwhelming popular sentiment in favor of ending this project. With our future on the line and the whole world watching, we’ll take a stand to bend the course of history.” Block Cop City is explicit that this will be a nonviolent direct action. Organizers will be going on a nationwide speaking tour and are encouraging autonomous affinity groups to travel to Atlanta for the action. The movement is going full bore in the direction of coaxing “outside agitation.”

The day after the jailhouse vigil was another demonstration planned in response to the RICO indictments. We would be meeting downtown in the early evening at Attorney General Chris Carr’s office, just across from the Georgia State Capitol. Across the street is the Central Presbyterian Church which does food and clothing distributions for the community. In the church’s yard flew a rainbow pride flag and Trans pride flag. Sitting and laying in the church’s doorways were about ten homeless people, some of them on their tablets, some of whom later joined the rally. The sidewalk smelled like piss. When I arrived at the rally site it was just me and two old women carrying signs. One of them, Lorraine, was known to me by reputation already, with her having been arrested for demonstrating against Home Depot for funding Cop City. There she was with her beautiful, long gray braids and her full-body protest sign draped around her neck. The sign read,

I’m here because Tortuguita can’t be. Stop Cop City.

At first I thought I was at the wrong place. There were only three of us and the street in front of the Justice Building was closed to all traffic. The building itself looked like it was gutted and under construction. I walked all the way around the block to make sure there wasn’t some place else we were supposed to be. When I got back to the starting point, more people had gathered, but it was still a pretty small group. At its height, around one hundred people made it to the rally. Given the broad criminalization of protest that the RICO charges represented, given the social media furor I had seen from some well-known figures, and given the size of Atlanta, I suppose I expected bigger numbers.

Two little kids dressed up as trees were leading the crowd in chants of “Protect the forest!” and “Stop Cop City!” The first person up to speak was Kamau Franklin, a leader with the local Community Movement Builders. When he first arrived, someone yelled, “Our fearless leader!” At this, the self-effacing Franklin looked behind him and pointed at someone else. Franklin reminded everyone that these RICO indictments, as worded, would have criminalized every person in the Civil Rights movement, and that this sets a worrying precedent for any organized dissent in the country. Franklin emphasized the intersecting struggles that the fight against Cop City and Atlanta’s attitude of business-as-usual represents.

Students, organizers, environmentalists, community people, young people, political organizers, you have represented the core elements that have kept this struggle going for nearly two-and-a-half years.

Also in attendance were members from the Party for Socialism and Liberation, some of whom were handing out flyers that read in part, “The indictment of Stop Cop City activists attempts to criminalize everything from handing out flyers, sharing links to independent media sources, and posting bail for protesters. It attempts to categorize a people’s movement to protect our civil liberties and the environment as a criminal enterprise.” One of the PSL members got on the megaphone and decried the Republican and Democratic Party unity on police oppression, saying neither party is the solution, and enjoining people to join a political organization, with the PSL representing a true alternative to the duopoly. After the event was over and people were milling about, someone was telling a PSL member holding a sign about the five people arrested at the construction site the day before. Then that person turned to me and said, “Oh my god, PSL vibes. How can you be here right now and not know what happened yesterday?” This wasn’t the first time I had heard negative comments from community members about PSL. The day before at the gathering point on campus for the Justice for Johnny Hollman march, when PSL members rolled up I heard student organizers comment, “Oh, here comes PSL,” and, “Man, they come to everything. At least they have Justice for Johnny Hollman signs.”

Also at the rally was community labor organizer Mariah Parker, who welcomed me with a winning smile and wink combo. After the event we exchanged fist bumps and Parker’s little son, sitting in Parker’s waist, put out his fist to me as well. I gently hit it. “Where did you learn that?” Parker said. “You have never done that before.” We talked about the upcoming day when all of the referendum signatures would be submitted to City Hall. “They need help moving boxes if you want to be there.” According to organizers, about 116,000 signatures have been collected, well above the necessary amount to get Cop City on the ballot, a deliberate defense to overcome any voter suppression efforts by the city. The city has already played obstructionist games with the referendum campaign by being vague with organizers about the amount of signatures required, instituting questionable signature verification techniques, and arguing in court that even a successful vote to stop Cop City would be legally invalid.

Parker and I also talked about the clear-cuts in the forest. “Ugh, it makes me so mad every time I see it.” Despite the bare landscape, Parker expressed optimism.

The forest burned down in the ’90s. The forest we knew, that was all growth just over the last thirty years. So it can come back.

Trees may grow back with time. But without first a fight, nothing is guaranteed. I remember that all the treaties in all the world, those worthless pieces of paper signed by the U.S. government and tribal nations—with such poetic and inarguable language as: “so long as grass grows or water runs”—did not protect the lives or lands or future means of survival of indigenous peoples. No matter what victories you secure, even legal ones, they can all be destroyed with the force of the gun. The Cherokee thought their lands were legally secured, and then the U.S. went on an ethnic cleansing campaign. One activist who attended the meeting with Cornel West reminded everyone that the state can always bring its most destructive power to bear:

What is the long term plan for the Cop City movement in particular, and also for leftists in general, when they do bring out the cavalry? They can arrest us in mass. They can harm us in mass. They can kill us in mass. Especially when they use the military, as we saw in Ferguson.

Without forest defenders, without those keeping vigil, without a constant reminder of our necessarily humble relationship to nature, without fighters and organizers and leaders and rebels and communities of resistance, all that was fought for goes away. Even with these webs of resistance in place, victory is far off indeed. Chainsaw justice is the final, catastrophic answer to the question of what does our society choose to value. Even for those who answer humanely, what does that really amount to in the shadow of amoral power? “As an environmentalist, you gotta win in court. Gotta win in congress. You gotta win in the media. Gotta win with the people,” said environmentalist Andy Stahl,

As a timber industry, you only have to win one of those. And once a tree is cut, it’s cut. Once you cut a 500 year-old tree—that’s never coming back.

~

On the day that the referendum signatures were submitted to Atlanta City Hall, Kamau Franklin stood in front of file boxes stacked in a pyramid, some of which were just props for the press conference, representing the 116,000 signatures that were collected by organizers. Those signatures amounted to more than the total votes cast in any recent municipal election, and nearly double what Mayor Andre Dickens received in his election. Franklin spoke to the crowd of citizens and reporters gathered on the steps next to the front door. “They have terrorized our movement. They have tried to break up our movement. At every turn and twist in which we’ve exercised our rights to the so-called democratic process, they’re response has been to try to put us down. But this movement will not be put down.” He went on, expressing the expansiveness of the struggle. “This won’t be our last day out here. We know there’s going to be different tactics and strategies that will keep this movement going for months and years to come. This movement is not only about stopping cop city. But this movement is about ending the Atlanta Way. No more backroom deals. No more making decisions without the people, ’cause today we’re here to say: let the people decide!” Shortly thereafter, an SUV pulled up to city hall and people began unloading additional file boxes of signatures onto dollies and rolling them into the building.

Once inside city hall, we were informed that the city would not be verifying the signatures pending a recent 11th Circuit Court of Appeals decision which stayed a previous federal court decision that gave an additional sixty days for signatures to be collected. Leaders immediately began organizing the one hundred or so activists in the building to speak with their city council representative and demand verification of the signatures. The Cop City Choir led people in song to keep the spirits up. Atlanta City Councilmember Liliana Bakhtiari arrived later. Passing by security at the front doors, she playfully grabbed the hat of a security guard and placed it backwards on his head. Bakhtiari is adroit with the press and is in favor of getting Cop City on the ballot. She was one of the few councilmembers who voted against funding Cop City originally. Speaking to a gang of press cameras, Bakhtiari said she had no idea beforehand that the city would not begin the signature verification process. Speaking to the Guardian, she said, “I’m livid. How can we expect people to have any faith in the democratic process when they keep moving the goalposts?”

While we were waiting for more information, I chatted with Timmy, one of the people who was arrested for blockading the construction site. “How are you doing?” I asked them, “Better now that I’m not in jail.” They felt that something had to be done immediately with how far along construction has come. “I really don’t want concrete to be poured.” They said that when they first joined the movement in Atlanta, they hadn’t realized how much of the forest had already been bulldozed. “When I saw it I could just feel my chest cave in. It’s so revulsive.” We talked about the need to keep obstructing the construction while the referendum campaign continues.

I got a do-not-return order. But the other 500,000 people who live in Atlanta didn’t. So I’ll just say that.

~

Weeks after 9/11, with the state’s anti-terrorism budget and rhetoric now exploding, Craig Rosebraugh, a spokesperson for Earth Liberation Front and Animal Liberation Front, was called to a congressional hearing on domestic terrorism. In a prepared statement to congress Rosebraugh said,

If the U.S. government is truly concerned with eradicating terrorism in the world, then that effort must begin with abolishing U.S. imperialism. Members of this governing body, both in the House and Senate as well as those who hold positions in the executive branch, constitute the largest group of terrorists and terrorist representatives currently threatening life on this planet.… If the people of the United States, who the government is supposed to represent, are actually serious about creating a nation of peace, freedom, and justice, then there must be a serious effort made, by any means necessary, to abolish imperialism and U.S. governmental terrorism. The daily murder and destruction caused by this political organization is very real, and so the campaign by the people to stop it must be equally as potent.

By any means necessary. People have been saying that phrase in Atlanta these days. Malcolm X is with us still. Mariah Parker was sworn in as county commissioner for Athens, Georgia on a copy of The Autobiography of Malcolm X. The cops are heeding the warning.

It was Rosebraugh’s sentiment that was floating in my head as I walked through the trails of the southern end of the Weelaunee Forest. Life is still there in that corner of the woods. But it’s getting smaller. Beyond a nearby dirt parking lot, past the dilapidated Thomasville Cemetery, across the train tracks, and through the closed-down landfill, police vehicles are posted up along Key Road, surveilling the entrances to the Cop City construction site. Uniformed officers sit in the shade on plastic chairs, sipping from big orange water containers under pop-up tents. Walking along the wooded path, I can hear them over the hill, there, the sound of chainsaws revving. The harsh buzzing stops me in my tracks. I stand still and just listen to the machines. Staying quiet. Soft focus on the trees all around me. I get chills. There’s a dead cicada in the mud at my feet. I blink slowly. The sound, the cutting, hurts. I think about what has already been lost. I think about the seemingly unstoppable march of degradation, in all of history, the many millions cut down in the fight for a better world. I think about my friends, Moss and Tyranny, and others like them. I think about the many clear cuts I’ve driven through in Oregon, those “moonscapes,” those “plucked chickens.” Every tree that is cut is a loss for us, forever. And it is a win for them. This is chainsaw justice. It is a form of violence. It is ecocide. It is terror.

The public referendum, just by getting the required amount of signatures to be put on the ballot, will be the first successful referendum campaign in Atlanta’s history. This is itself a win, perhaps. We have yet to see how the latest legal hurdle will be overcome. Some city councilmembers, Bakhtiari among them, have pledged to bring a resolution for Cop City to be put on the ballot, circumventing the court’s quagmire. Even if it does get on the ballot, the people of Atlanta may or may not vote to stop Cop City. And regardless of the vote outcome, the trees have been cut. What will the movement do going forward? “Our memory is long,” said one organizer on the day the signatures were submitted to city Hall. If the vote fails, they will continue to organize, she said.

Another term that has made its way to the movement is “diversity of tactics.” This is where the extralegal means come in. Though Cop City has garnered international attention, I have so far not seen the kind of consistent numbers being brought to bear for militant civil disobedience that are required for making deforestation and construction truly untenable. The impending mass action being organized by Block Cop City in November is exactly the kind of broad-based militancy that is needed in this moment of devastation. “Seeing them chain themselves to the construction equipment relieved some of my grief,” one activist named Jaye told me. “I was really grieving. I couldn’t get people to come out to the site with me. Forget November, we need to be out there tomorrow.”

Aside from the hard skills of climbing trees and surviving in the forest and dealing with riot police and knocking on doors and organizing phone banking and navigating the byzantine legal system, the movement in Atlanta is learning to deal with what so many other movements have learned before them: That working on the frontlines is to be burned out, hounded out, laughed at, shot at, imprisoned, almost always disappointed, heartbroken over the irrevocable, yet still struck by brief glimpses and flashes of bright, radical, resilient, selfless action, and thus, holding on to the only things that give anyone the right to talk about hope.

Long Live Weelaunee.