The Russo-Ukrainian War has been a novel historical experience for a variety of reasons, and not only for the intricacies and technicalities of the military enterprise itself. This became the first conventional military conflict to occur in the age of social media and planetary cinematography (that is, the ubiquitous presence of cameras). This brought a veneer (though only a veneer) of immanence to war, which for millennia had unveiled itself only through the mediating forces of cable news, print newspapers, and victory steles.

For the eternal optimist, there were upsides to the idea that a high intensity war was slated to be documented in thousands of first-person view videos. Purely from the standpoint of intellectual curiosity (and martial prudence), the flood of footage from Ukraine offers insight into emerging weapons systems and methods and allows for a remarkable level of tactical-level data. Rather than waiting for years of agonizing dissection of after action reports to reconstruct engagements, we are aware in near real time of tactical movements.

Unfortunately, all the obvious downsides of airing a war live on social media were also in effect. The war instantly became sensationalized and saturated with fake, fabricated, or incorrectly captioned videos, cluttered with information that most people are simply not equipped to parse through (for obvious reasons, the average citizen does not have extensive experience differentiating between two post-Soviet armies using similar equipment and speaking similar, or even the same language), and pseudo-expertise.

More abstractly, the war in Ukraine was transformed into an American entertainment product, complete with celebrity wonder weapons (like Saint Javelin and the HIMARS), groan-inducing references to American pop culture, visits from American celebrities, and voiceovers from Luke Skywalker. All of this fit very naturally with American sensibilities, because Americans ostensibly love underdogs, and in particularly spunky underdogs who overcome extreme odds through perseverance and grit.

The problem with this favored narrative structure is that underdogs rarely win wars. Most major peer conflicts do not have the conventional Hollywood plot structure with a dramatic turning point and reversal of fortune. Most of the time, wars are won by the more powerful state, which is to say the state with the ability to mobilize and effectively apply more fighting power over a longer period of time. This has certainly been the case in American history—no matter how much Americans may long to recast themselves as a historical underdog, America has historically won its wars because it has been an exceptionally powerful state with irresistible and innate advantages over its enemies. This is nothing to be ashamed of. As General George Patton famously said: Americans love a winner.

Thus we arrived at a convolution situation where, despite Russia’s many obvious advantages (which in the end come down to a superior indigenous capacity to mobilize men, industrial output, and technology), it became “propaganda” to argue that Russia was going to achieve some sort of victory in Ukraine—that Ukraine would end the war having failed to re-attain its 1991 borders (Zelensky’s stated victory condition) and with the country in a wrecked state of demographic hollowing and material destruction.

At last, we seem to have reached a denouement phase, where this view—allegedly an artifact of Kremlin influence, but in reality the most straightforward and obvious conclusion—is becoming inescapable. Russia is a bigger fighter with a much bigger bat.

The case for Ukraine’s victory rested almost entirely on dramatic success in a summer counteroffensive, which was supposedly expected to smash its way through the Russian positions in Zaporizhia Oblast, knife to the Sea of Azov, sever Russia’s land bridge to Crimea, and place the entire underbelly of Russia’s strategic position in jeopardy. A whole host of assumptions about the war were to be tested: the supremacy of western equipment, Russia’s paucity of reserves, the superiority of Western-Ukrainian tactical methods, the inflexibility and incompetence of Russian commanders in the defense.

Debacle: The Battle of Robotyne

More generally—and more importantly—this was intended to prove that Ukraine could successfully attack and advance against strongly held Russian positions. This is obviously a prerequisite for a Ukraine strategic victory. If the Ukrainian armed forces cannot advance, then Ukraine cannot restore its 1991 boundaries and the war has transformed from a struggle for victory into a struggle for a managed or mitigated defeat. The issue ceases to be whether Ukraine will lose, and becomes a question only of how much.

Ukraine’s Summer Calamity

Remembering that the Ukrainians and their benefactors genuinely believed that they could reach the Azov coast and create an operational crisis for Russia is very important, because only in the context of these objectives can the letdown of the attack be fully comprehended. We are now (as of my typing of this sentence) at D+150 from the initial massed Ukrainian assault on the night of June 7-8, and the gains are paltry to say the least. The AFU is stuck in a concave forward position, wedged between the small Russian held villages of Verbove, Novoprokopivka, and Kopani, unable to advance any further, taking a steady trickle of losses as it attempts half-hearted small unit attacks to cross the Russian anti-tank ditches that ring the edges of the fields.

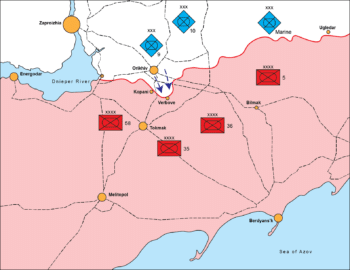

At the moment, the maximum advance achieved by the counteroffensive lies just ten miles from the town of Orikhiv (in the Ukrainian staging area). Ukraine failed not only to reach its terminal objectives, but it never even threatened its intermediate waypoints (like Tokmak). In fact, they never created even a temporary breach in Russia’s defenses. Instead, the AFU threw the bulk of the newly formed and western-equipped 9th and 10th Corps against fixed positions of the Russian 58th, 35th, and 36th Combined Arms Armies, became embedded in the outer screening line, and the attack collapsed after heavy casualties.

As the autumn began to drag on without battlefield results materializing for Ukraine, the process of finger pointing began with remarkable predictability. Three distinct lines of thought emerged, with observers in the west blaming a supposed Ukrainian inability to implement western tactics, some Ukrainian parties countering that western armor was too slow to arrive, which gave the Russian army time to fortify its positions, and others arguing that the problem was that the west failed to provide the necessary aircraft and strike systems.

I think that all of this rather misses the point—or rather, all of these factors are merely tangential to the point. The various Ukrainian and western figures pointing fingers at each other are rather like the proverbial blind men describing an elephant. All of these complaints—insufficient training, slow delivery timetables, shortages of air and strike assets—merely reflect the larger problem of attempting to assemble on an improvised basis an entirely new army with a hodgepodge of mismatched foreign systems, in a country with dwindling demographic and industrial assets.

All that aside, the internecine quarreling in the Ukrainian camp obscures the importance of tactical factors and ignores the highly active role that the Russian armed forces played in spoiling Ukraine’s great attack. While the dissection of the battle is likely to continue for many years, a litany of tactical reasons for Ukrainian defeat can already be enumerated as follows:

- The failure of the AFU to achieve strategic surprise. Notwithstanding an ostentatious OPSEC effort and attempted feint operations on the Belgorod border, around Bakhmut, Staromaiorske, and elsewhere, it was readily apparent to all involved that the point of the main Ukrainian effort would be towards the Azov littoral, and specifically the Orikhiv-Tokmak axis. Ukraine attacked precisely where they were expected to.

- The danger of staging and approach in the 21st century. The AFU had to congregate assets under exposure to Russian ISR and strike assets, which repeatedly subjected Ukrainian rear areas (like Orikhiv, where ammunition dumps and reserves were repeatedly struck) to Russian fire, and allowed the Russians to routinely take deploying Ukrainian battlegroups under fire while they were still in their marching columns.

- Inability (or unwillingness) to commit sufficient mass to force a decision. The density of the Russian ISR-Fires nexus incentivized the AFU to disperse its forces. While this can reduce losses, it also meant that Ukrainian combat power was introduced in a piecemeal trickle which simply lacked the mass to ever seriously threaten the Russian position. The operation largely devolved into company-level attacks which were clearly inadequate for the task.

- Inadequacy of Ukrainian fires and suppression. A fairly self-evident and all-encompassing capabilities gap, with the AFU facing a shortage of tubes and artillery shells (forcing HIMARS into a tactical role as an artillery substitute), and lacking sufficient air defense and electronic warfare assets to mitigate the variety of Russian airborne systems, including drones of all types, attack helicopters, and UMPK bombs. The result was a series of under-supported Ukrainian maneuver columns being raked in a firestorm.

- Inadequate combat engineering, which left the AFU vulnerable to a web of Russian minefields that were evidently far more robust than expected.

Taken together, we actually have a fairly straightforward tactical conundrum. The Ukrainians attempted a frontal assault on a fixed defense without either the element of surprise or parity in ranged fires. With the Russian defense fully on alert and Ukrainian staging areas and approach lanes subject to intense Russian fires, the AFU dispersed its forces in an effort to reduce losses, and this all but ensured that the Ukrainians would never have the necessary mass to create a breach. Add it all up, and you get the summer of 2023—a series of frustrating and fruitless attacks on the exact same sector of the defense, slowly frittering away both the year and Ukraine’s best, last hope.

The failure of Ukraine’s offensive has seismic ramifications for the future conduct of the war. Combat operations always occur in reference to Ukraine’s political objectives, which are—to put it bluntly—ambitious. It’s important to remember that the Kiev regime has maintained from the very beginning that it would not settle for anything less than the 1991 territorial maximum of Ukraine—implying not only the recovery of the territory occupied by Russia after February 2022, but also the subjugation of the separatist polities in Donetsk and Lugansk and the conquest of Russian Crimea.

Ukraine’s war aims have always been defended as reasonable in the west for reasons related to the supposed legal niceties of war, the western illusion that borders are immutable, and the apparent transcendent divinity of Soviet-era administrative boundaries (which after all were the source of the 1991 borders). Regardless of all these matters, what Ukraine’s war aims implied as a practical matter was that Ukraine needed to capture de-facto prewar Russian territory, including four major cities (Donetsk, Lugansk, Sevastopol, and Simferopol). It meant dislodging the Russian Black Sea Fleet from its port somehow. This was an extraordinarily difficult task—far more complicated and more vast than anyone wanted to admit.

The obvious problem, of course, is that given Russia’s superior industrial resources and demographic reservoir, Ukraine’s only viable pathways to victory were either a Russian political collapse, Russian unwillingness to fully commit to the conflict, or the inflicting of some astonishing asymmetric battlefield defeat on the Russian army. The first now clearly seems like a fantasy, with the Russian economy shrugging off western sanctions and the political cohesion of the state completely unperturbed (even by the Wagner coup), and the second hope was dashed the moment Putin announced mobilization in the autumn of 2022. That leaves only the battlefield.

The obvious problem, of course, is that given Russia’s superior industrial resources and demographic reservoir, Ukraine’s only viable pathways to victory were either a Russian political collapse, Russian unwillingness to fully commit to the conflict, or the inflicting of some astonishing asymmetric battlefield defeat on the Russian army. The first now clearly seems like a fantasy, with the Russian economy shrugging off western sanctions and the political cohesion of the state completely unperturbed (even by the Wagner coup), and the second hope was dashed the moment Putin announced mobilization in the autumn of 2022. That leaves only the battlefield.

Therefore, the situation becomes very simple. If Ukraine cannot successfully advance on strongly held Russian positions, it cannot win the war according to its own terms. Thus, given the collapse of Ukraine’s summer offensive (and myriad other examples, like the way an ancillary Ukrainian attack banged its head meaninglessly on Bakhmut for months) there is a very simple question to be asked.

Will Ukraine ever get a better opportunity to attempt a strategic offensive? If the answer is no, then it necessarily follows that the war will end with Ukrainian territorial loss.

It seems to be a point of near triviality that 2023 was Ukraine’s best opportunity to attack. NATO had to move heaven and earth to scrape together the attack package. Ukraine will not get a better one. Not only is there simply nothing left in the stable for many NATO members, but assembling a larger mechanized force would require the west to double down on failure. Meanwhile, Ukraine is hemorrhaging viable manpower, due to a combination of high casualties, a flood of emigration as people flee a crumbling state, and endemic corruption which cripples the efficiency of the mobilization apparatus. Add it all up and you get a growing manpower squeeze and looming shortages of munitions and equipment. This is what it looks like when an army is attrited.

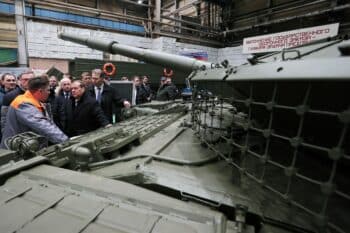

At the same time that Ukrainian combat power is declining, Russia’s is climbing. The Russian industrial sector has dramatically increased output despite western sanctions, leading to belated recognition that Russia is not going to conveniently run out of weapons, and indeed is comfortably out-producing the entire western bloc. The Russian state is in the process of radically raising defense expenditures, which will pay further dividends in combat power as time goes on. Meanwhile, on the manpower front, Russian force generation is stable (IE, does not require an expanded mobilization), and the sudden realization that the Russian army does in fact have plenty of reserves left prominent members of the Commentariat arguing with each other on Twitter. The Russian army is now poised to reap the benefits of its investments over the coming year.

The picture is not overly complicated. Ukrainian combat power is in a decline which has little chance of arrest, particularly now that events in the Middle East mean that it no longer has an uncontested claim to western stocks. There are a few things the west can still do to try and prop up Ukrainian capabilities (more on that later), but Meanwhile, Russian combat power is stable and even rising in many arms (note, for example, the steady increase in Russian UMPK drops and FPV drone strikes, and the growing availability of the T90 tank).

The picture is not overly complicated. Ukrainian combat power is in a decline which has little chance of arrest, particularly now that events in the Middle East mean that it no longer has an uncontested claim to western stocks. There are a few things the west can still do to try and prop up Ukrainian capabilities (more on that later), but Meanwhile, Russian combat power is stable and even rising in many arms (note, for example, the steady increase in Russian UMPK drops and FPV drone strikes, and the growing availability of the T90 tank).

Ukraine will not recover its 1991 borders, and is unlikely to recapture any meaningful territories going forward. Thus, language has shifted sharply from references to retaking lost territories to merely freezing the front. None other than Commander in Chief Zaluzhny has admitted that the war is stalemated (an optimistic construction), while some western officials have begun to float the idea that a negotiated settlement(which would necessarily entail acknowledging the loss of Russian-held territories) may be Ukraine’s best path out.

This does not imply that the war is nearing an end. Zelensky continues to be adamantly against negotiations, and there are certainly plenty in the west who s upport continuing Ukrainian intransigence, but I think rather they are all missing the point.

There is only one way to end a war unilaterally, and that is by winning. It may very well be that the window to negotiate is over, and that Russia is ramping up its spending and expanding its ground and aerospace forces because it intends to use them to attempt a decisive victory on the battlefield.

We will likely see an increasingly vigorous debate in the coming months as to whether or not Kiev ought to negotiate. But the premise of this debate may well be wrong in toto. Maybe neither Kiev nor Washington gets to decide.

Avdiivka: Canary in the Coal Mine

The Avdiivka Battlespace

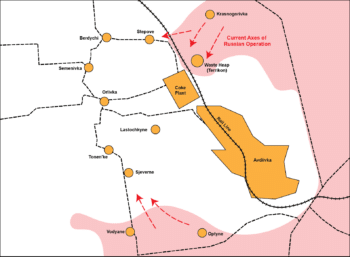

Avdiivka was already in something of a salient, owing to previous Russian operations which had captured the town of Krasnogorivka, to the north of the city. Over the month of October, Russian forces launched a large assault out of these positions and successfully captured one of the key terrain features in the area—a tall mound of discarded mining byproduct (a spoil heap) which directly overlooks the main railway into Avdiivka, and lies adjacent to the Avdiivka coke plant. As of this writing, the situation looks like so:

The Avdiivka operation almost immediately spawned a familiar cycle of dooming and histrionics, with many getting ready to compare the attack to Russia’s failed assault on Ugledar last winter. Despite successful Russian capture of the waste heap (along with positions along the railway), the Ukrainian sphere was pleased, claming that the Russians are suffering catastrophic losses in their assault on Avdiivka. However, I think that this fails to hold water for a few reasons.

First and foremost, the premise itself does not obviously appear to be true. This war is being eagerly documented in real time, which means we can actually check for a sharp increase in Russian losses in the tabulated data. For this, I prefer to check in with War Spotting UA and their Russian equipment loss tracking project. While they have an overtly pro-Ukrainian orientation (they track only Russian and not Ukrainian losses), I think they are more reliable and reasonable than Oryx, and their tracking methodology is certainly more transparent.

A quick note about their data is important. First, it’s incorrect to be overly focused on the precise dates that they ascribe to losses—this is because their logged dates correspond to the date that losses are first photographed, which may or may not be the same day the vehicle is destroyed. When they log a date for a destroyed vehicle, they are logging only the date the picture was taken. It’s thus reasonable to pencil in a few days worth of potential error on the dating of losses. This simply can’t be helped. Furthermore, they—like anyone else—have the capacity to misidentify or accidentally double count vehicles filmed from different angles.

All that is to say, it’s not useful to get too bogged down looking at specific loss clusters and photos, but looking at the trends in their loss tracking is very useful. If Russia was really losing an inordinate amount of equipment in a month-long assault, we would expect to see a spike, or at least a modest level increase in losses.

In fact, that’s not apparent in the loss data. Russia’s overall burn rate from the summer of 2022 until now comes out to approximately 8.4 maneuver assets per day. Yet the losses for the autumn of 2023 (which includes the Avdiivka assault) are actually slightly lower, at 7.3 per day. There are a few batches of losses, which correspond to the aftermath of assaults, but these are not abnormally large—a fact that can be easily checked by referencing the time series of losses. The data shows a modest increase from the summer of this year (6.8 per day) to the autumn (7.3), which corresponds to a shift from a defensive to an attacking posture, but there is simply nothing in the data here that suggests an abnormal elevation in Russian loss rates. Overall, the loss data suggests a high intensity attack, but the losses overall are lower than in other periods where Russia has been on the offensive.

We can apply the same basic analytic framework to personnel losses as well. Mediazona—an anti-Putinist Russian dissident media outlet—has been dutifully tracking Russian casualties via obituaries, funerary announcements, and social media posts. Lo and behold, they—like Warspotting UA—fail to record an inordinate spike in Russian losses through the Autumn thus far.

Now, it would be silly to deny that Russia lost armored vehicles or that attacking does not incur costs. There is a battle being fought, and vehicles are destroyed in battles. That is not the question here. The question is whether the Avdiivka assault has caused an unsustainable or abnormal spike in Russian losses, and quite simply there is nothing in the tracked loss data that would suggest this. Therefore, the argument that Russian forces are being eviscerated at Avdiivka simply does not seem supported by the available information, and so far the tracked daily losses for Autumn are simply lower than the average over the previous year.

Furthermore, fixation on Russian losses can lead one to forget that the Ukrainian forces get badly chewed up as well, and we actually have v ideos from the Ukrainian 110th Brigade (the main formation anchoring the Avdiivka defense) complaining that they have taken unsustainable losses. All to be expected with a high intensity battle underway. The Russians attacked in force in force and took proportional losses—but was it worth it?

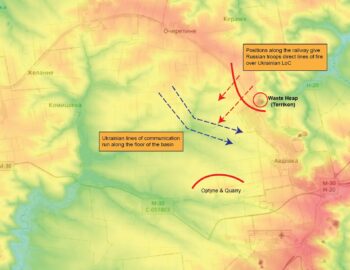

We need to think about that initial Russian assault in the context of the Avdiivka battlespace. Avdiivka is rather unique in that the entire city and the railway running towards it sit upon an elevated ridge. With the city now enveloped on three sides, remaining Ukrainian logistical lines run along the floor of a wetland basin to the west of the city—the only corridor that remains open. Russia now has a position on the dominating heights that directly overlook the basin, and are in the process of expanding their position along the ridge. In fact, contrary to the claim that the Russian assault collapsed with heavy casualties, the Russians continue to expand their zone of control to the west of the railway, have already breached the outskirts of Stepove, and are pushing into the fortified trench network in southeastern Avdiivka proper.

Avdiivka Elevation Map

Now, at this point it’s probably rational to want to compare the situation to Bakhmut, but the AFU forces in Avdiivka are actually in a much more dangerous position. Much was made of so-called “fire control” during the battle for Bakhmut, with some insinuating that Russia could isolate the city simply by firing artillery at the supply arteries. Needless to say, this didn’t quite pan out. Ukraine lost plenty of vehicles on the road in and out of Bakhmut, but the corridor remained open—if dangerous—until the very end. In Avdiivka, however, Russia will have direct ATGM line of sight (rather than spotty artillery overwatch) over the supply corridor on the floor of the basin. This is a much more dangerous situation for the AFU, both because Avdiivka has the unusual feature of a single dominating ridge on the spine of the battlespace, and because the dimensions are smaller—the entire Ukrainian supply corridor here runs along a handful of roads in a 4 kilometer gap.

Clearly, control of the waste heap and the rail line are of paramount importance, so the Russian Army committed a significant assault force to ensure the capture of their key objectives. Attacking the waste heap furthermore required exposing Russian attack columns to perpendicular Ukrainian fire, attacking across well surveilled ground. In short, this entailed many of the tactical problems that plagued the Ukrainians over the summer. Modern ISR-fire linkages make it very difficult to successfully stage and deploy forces without incurring losses.

Unlike the Ukrainians, however, the Russians committed sufficient mass to create an irreversible snowball in the attack on the commanding heights, and Ukrainian fires were inadequate to stymie the assault. Now that they have them, the Russians will recoup losses as the Ukrainians attempt to counterattack—indeed, this has already begun, with UA Warspotting recording a sharp drop in Russian equipment losses over the last three weeks. This establishes the pattern of the operation—a massed assault early to capture keystone positions that put the Russians in control of the battlespace. The Russians successfully forced a decision from the get-go by committing to their attack with a level of violence and force generation that was lacking all summer for the AFU. The juice is worth the squeeze.

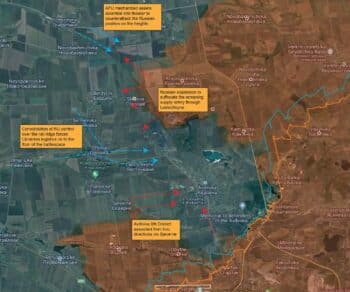

More to the point, the Ukrainians clearly know that they are in trouble. They have already begun scrambling premier assets to the area to begin counterattacking against the Russian position on the ridge, and there are already Bradleys and Leopards burning around Avdiivka and in the Ukrainian staging areas in the rear. The same basic problem now exists which proved so insurmountable in the summer: counterattacking Ukrainian forces (staging over ten kilometers in the rear, past Ocheretyne) face long and well-surveilled lines of approach which expose them to Russian standoff fires—the Ukrainian 47th Mechanized Brigade has now already lost armored vehicles both in its staging areas and in failed counterattacks on Russian positions around Stepove.

In the coming weeks, Russian forces will carry their momentum forward into attacks on the axes through Stepove and Sjeverne to the west of the city, leaving the AFU tied to a long and precarious logistical chain on the floor of the basin. One of Ukraine’s longest and most strongly held fortresses now threatens to become an operational trap. I don’t expect Avdiivka to fall in a matter of weeks (barring an unforeseen and unlikely collapse in the Ukrainian defense), but it is now a matter of time and the winter months will likely bring the steady whittling away of the Ukrainian position here.

Anticipated future developments around Avdiivka

Sustaining AFU combat power in the city will be particularly difficult, with Ukrainian “mosquito logistics” (referring to their habit of running supply lift with pickup trucks, vans, and other small civilian vehicles) struggling across the floor of a muddy basin under the watchful eye of Russian FPV drones and direct fire. The AFU will be forced to attempt to sustain a brigade-level defense by running small vehicles through a beaten zone. If the Russians successfully capture the coke plant, the game will end much sooner, but the Ukrainians know this and will make the defense of the plant a preeminent priority—but even so, it is only a matter of time, and once Avdiivka falls, the Ukrainians do not have a solid place to anchor their defense until they fall all the way back to the Vocha River. This is a process that should play itself out through the winter.

And that begs the question: if Ukraine could not hold Bakhmut, and time proves that they cannot hold Avdiivka, where can they hold? And if Ukraine cannot successfully attack, what are they fighting for?

A failed defense only counts as a delaying action if you have something to look forward to.

Strategic Exhaustion

With the Russians facing with a much larger war than anticipated, and with utterly inadequate force generation for the task, the war took on the character of industrial attrition as it moved into the second phase. This phase was characterized by Russian attempts to shorten and correct the frontline, creating dense fortifications and locking up forces in grinding positional battles. This phase, more generally, was about the Ukrainians attempting to exploit—and the Russians enduring—a period of Ukrainian strategic initiative as Russia moved to a more expansive war footing, expanding armaments production and raisings force generation through mobilization.

In essence, Ukraine faced a dire strategic dilemma from the moment President Putin announced the mobilization of reserves in September, 2022. The Russian decision to mobilize was a de-facto signal that it accepted the new strategic logic of a longer war of industrial attrition—a war in which Russia would enjoy numerous advantages, including a much larger pool of manpower, vastly superior industrial capacity, indigenous production of standoff weaponry, armored vehicles, and shells, an industrial plant beyond the reach of systematic Ukrainian attacks, and strategic autonomy. These, however, are all systemic and long-term advantages. In the shorter term, however, Ukraine enjoyed a brief window of initiative on the ground. This window, however, was squandered with the botched summer assault on Russia’s defenses in the south, and the second phase of the war ends alongside the AFU’s drive on the Azov shore.

And so we come to the third phase, characterized by three important conditions:

- Steadily rising Russian combat power as a result of investments made over the previous year.

- Exhaustion of Ukrainian initiative on the ground and increasing self-cannibalization of AFU assets.

- Strategic exhaustion in NATO.

The first point is relatively trivial to comprehend and has been freely confessed by western and Ukrainian authorities. It is now well understood that sanctions failed to make a meaningful dent in Russian armaments production, and in fact the availability of critical systems is growing rapidly as a result of strategic investments in new and expanded production lines. However, we can enumerate a few examples of this.

One of the key elements of expanding Russian capabilities has been both the qualitative and quantitative improvement in new standoff systems. Russia has successfully launched mass production of the Iranian-derived Shahed/Geran drone, and has an additional factory under construction. Production of the Lancet loitering munition has risen exponentially, and a variety of improved variants are now entering use, with superior guidance, effective range, and swarming capabilities. Russian production of FPV drones has risen significantly, with Ukrainian operators now fearing a snowballing Russian advantage. UMPK guided glider adaptations have been modified to accommodate much of the Russian arsenal of gravity bombs.

One of the key elements of expanding Russian capabilities has been both the qualitative and quantitative improvement in new standoff systems. Russia has successfully launched mass production of the Iranian-derived Shahed/Geran drone, and has an additional factory under construction. Production of the Lancet loitering munition has risen exponentially, and a variety of improved variants are now entering use, with superior guidance, effective range, and swarming capabilities. Russian production of FPV drones has risen significantly, with Ukrainian operators now fearing a snowballing Russian advantage. UMPK guided glider adaptations have been modified to accommodate much of the Russian arsenal of gravity bombs.

All of this speaks to a Russian military with an expanding capacity to fling high explosives in greater numbers and accuracy at AFU personnel, equipment, and installations. Meanwhile, on the ground, tank production continues to rise, with sanctions having little apparent impact on Russian armor availability. In contrast to previous predictions that Russia would begin scraping the bottom of the barrel, pulling ever older tanks out of storage, Russian forces in Ukraine are fielding *newer* tanks, with the T-90 appearing on the battlefield in greater numbers. And, despite repetitive western predictions that a new mobilization wave would be required in the face of supposedly horrific casualties, the Russian defense ministry has confidently said that its manpower reserves are stable, and a Ukrainian military intelligence spokesman recently said that they believe there are over 400,000 Russian troops in the theater (to which can be added the sizeable reserves that remain in Russia).

Meanwhile, Ukrainian forces are likely to become increasingly self-cannibalizing. This occurs on multiple levels, as a motif of a strategically exhausted force. On the strategic level, self-cannibalization occurs when strategic assets are burned off in the name of short term exigencies; on the tactical level, a similar degradative process occurs when formations remain in combat for too long and begin to grind away as they attempt combat tasks for which they are no longer suited.

You’re likely rolling your eyes at that paragraph, and understandably so. It’s heavily jargonized, and I apologize for it. However, we can see a concrete example of what both forms of self-cannibalization (strategic and tactical) look like, from the same unit: the 47th Mechanized Brigade.

The 47th was slated long ago to become one of the premier assets in Ukraine’s counteroffensive. Trained (as best as time allowed) to NATO standards and with privileged access to high-end western equipment like the Leopard 2A6 Tank and the Bradley IFV. This brigade was both meticulously prepared and widely advertised as the deadly tip of the spear for Ukraine. However, a summer of frustrating and failed attacks on Russia’s Zaporizhia line l eft the brigade with severe losses, degraded combat power, and infighting among the officers.

The iconic image of modern war: mountains of discarded shell casings

What followed ought to raise red flags. First, in early October it was reported that the 47th had a new commander, with the change spurred by demands from above that the brigade continue its efforts to attack. The problem was that the 47th had gradually exhausted its attacking potential, and the solution implemented by the new commander was to scrounge the brigade’s rear areas and technical crews for replacement manpower. As the MilitaryLand report reads:

As claimed by soldiers of anti-tank missile unit of Magura in now removed video appeal, the brigade’s command refuse to admit the brigade lost its offensive potential. Instead, command sends mortar crews, snipers, artillery crews, basically all it has available to the front as assault infantry.

This is a classic example of tactical self-cannibalization, wherein a loss in combat power threatens to accelerate as ancillary and technical elements of the unit are burned off in an attempt to compensate for losses. However, the 47th is also been cannibalized on the strategic level. When the Russian assault around Avdiivka began, the Ukrainian response was to pull the 47th out of the Zaporizhia front and scramble it to Avdiivka to counterattack. At this point, the Ukrainian defense there depends on the 110th Brigade, which has been in Avdiivka for nearly a year without relief, and the 47th, which was already degraded from months of continuous offensive operations in the south.

This is strategic cannibalization: taking one of the premier assets in the stable and rushing it, with no rest or refitting whatsoever, directly into combat as a defensive exigency. Thus, you have the 47th Brigade being cannibalized on an internal level (burning itself off as it attempts combat tasks that it is no longer appropriately equipped for) and on a strategic level, with the AFU grinding it down in a positional defense around Avdiivka rather than rotating it out for rest and refit to be earmarked for future offensive operations. A recent report with interviews of 47th personnel painted a dire picture: the brigade had lost over 30% of its personnel over the summer and its howitzers are rationed to a mere 15 shells per day. Russian mortars, they say, have an eight to one advantage.

The situation can be vaguely likened to a person in crisis, who wears themselves down biologically and emotionally through a lack of sleep and stress, while also burning away their assets—selling their car and other critical possessions to pay for immediate necessities like food and medicine. This is an unsustainable way to live, and cannot stave off catastrophe indefinitely.

The Russians are doing everything they can to encourage this process, methodically reactivating grinding attacking operations across the breadth of the front, including not only Avdiivka but also at Bakhmut and Kupyansk, in an intentional pinning program designed to keep Ukrainian assets in combat after being exhausted over the summer. The 47th is emblematic of this—attacking all summer only to immediately be scrambled into defense in the Donbas. As one associate of mine put it, the last thing you want to do after running a marathon is begin a sprint, and this is where the Ukrainians find themselves after losing the strategic initiative in October.

It is not just Ukraine, however, that faces strategic exhaustion. The United States and the NATO bloc find themselves in a similar situation.

The entire American strategy in Ukraine has worked its way into an impasse. The logic of the proxy war lay in assumptions about a cost differential—that the United States could stymie Russia for pennies on the dollar, supplying Ukraine out of its surplus inventories while strangling the Russian economy with sanctions.

Not only have sanctions failed to cripple Russia, but the American approach on the ground has come up bust. Ukraine’s counteroffensive failed spectacularly, and the depleted Ukrainian ground force now must contrive a full-spectrum strategic defense against rising Russian force generation.

The basic strategic quandary for the west, then, is how to get out of a strategic cul-de-sac. NATO has reached the limits of what it can give Ukraine out of surpluses. In regards to artillery shells (the totem item in this war), for example, NATO allies have openly admitted that they have more or less run out, while the United States has been forced to r edirect shell deliveries from Ukraine to Israel—a tacit admission that there are not enough on hand for both. Meanwhile, new production of shells is behind schedule in both the United States and Europe.

Facing a massive Russian investment in defense production and the following enormous ramp in Russian capabilities, it’s not clear how the United States can proceed. One possibility is the “all-in” option, which would require industrial restructuring and de-facto economic mobilization, but it’s not clear how this could be achieved given the parlous state of both the western industrial base and its finances.

Indeed, there are unmistakable signs that bringing western arms manufacturing out of its deep freeze will be enormously expensive and logistically challenging. New contracts demonstrate exorbitant cost runup. For example, a recent Rhenmetall order clocked in at $3500 per shell—an astonishing increase when one considers that as recently as 2021 the U.S. Army was able to procure at a mere $820 per shell. No wonder the head of NATO’s Military Committee complained that higher prices are defeating efforts to build up stockpiles. Meanwhile, production is constrained by a lack of skilled workers and machine tools. Going “all in” on Ukraine would require a level of breakneck economic restructuring and mobilization that western populations would likely find intolerable and confusing.

A second option is “freezing” the conflict by pushing Ukraine to negotiate. This has already been broached in public by American and European officials, and was received with mixed reviews. On the whole, this seems rather unlikely. Opportunities to negotiate an end to the conflict were rebuffed on multiple occasions. From the Russian perspective, the west deliberately chose to escalate the conflict and would now want to walk away after Russia answered with its mobilization. It’s not clear then why Putin would be inclined to let Ukraine off the hook now that Russian military investments are beginning to bear fruit, and the Russian army has the real possibility of walking away with the Donbas and more. Even more troubling, however, is Ukrainian intransigence, which seems bound to sacrifice more brave men attempting to prolong Kiev’s fingerhold grip on territories that cannot be held indefinitely.

In essence, the United States (and its European satellites) have four options, none of which are good:

- Commit to an economic mobilization to substantially ramp up material deliveries to Ukraine

- Continue the extant trickle of support to Ukraine and watch it suffer a progressive and slow defeat

- End support for Ukraine and watch it suffer a more rapid and totalizing defeat

- Attempt to freeze the conflict with negotiations

This is a classic formula for strategic paralysis, and the most likely outcome is that the United States will default to its current course of action, supporting Ukraine at a trickle level commensurate with the financial and industrial limits in place, keeping the AFU in the field but ultimately overmatched in myriad dimensions by rising Russian capabilities.

And this, ultimately, brings us back where we started. There is no wonder weapon, no cool trick, no operational contrivance coming to save Ukraine. There is no exhaust port on the Death Star. There’s only the cold calculus of massed fires over time and space. Even Ukraine’s isolated successes only serve to emphasize the enormous disparity in capabilities. For example, when the AFU uses western missiles to attack Russian ships in drydock, this is only possible because Russia has a navy. The Russians, in contrast, have a wide arsenal of anti-ship missiles that they are not using, because Ukraine does not have a navy. While the spectacle of a successful hit on a Russian vessel makes for nice PR, it only reveals the asymmetry in assets and does nothing to ameliorate Ukraine’s fundamental problem, which is the steady attrition and destruction of its ground forces in the Donbas.

As 2024 brings a steady erosion of the Ukrainian position in the Donbas—isolation and liquidation of peripheral fortresses like Adviivka, a double pronged advance on Konstyantinivka, an ever more severe salient around Ugledar as the Russians advance on Kurakhove—Ukraine will find itself in an ever more untenable place, with western partners questioning the logic of funneling limited weapons stocks into a shattered state.

In the third century, during China’s Three Kingdoms era (after the Han Dynasty broke apart into a trifurcated state in the early 200’s), there was a famous general and official named Sima Yi. While not as oft quoted as the better known Sun Tzu, Sima Yi has one pithy aphorism attributed to him which is better than anything in the Art of War. Sima Yi put the essence of warmaking the following way:

In military affairs there are five essential points. If able to attack, you must attack. If not able to attack, you must defend. If not able to defend, you must flee. The remaining two points entail only surrender or death.

Ukraine is working its way down the list. The events of the summer demonstrated that it cannot successfully attack strongly held Russian positions. Events in Avdivvka and elsewhere now test whether they can defend their position in the Donbas against rising Russian force generation. If they fail this test, it will be time to flee, surrender, or die. Such is the way of things when the time for reckoning comes.