While Australia switches off to take its long summer break, Indonesia is seized by election fever. On 14 February 2024, over 200 million Indonesians will decide who to elect as their new president, members of parliament, provincial and municipal representatives.

Of the three men who seek to be Indonesia’s next president, one stands out. Not because he is Indonesia’s Barack Obama, but for less flattering reasons. The candidate in question is Prabowo Subianto.

Prabowo differs from his competitors in the presidential race, Ganjar Pranowo and Anies Baswedan, in significant ways. These include his pre-reformasi connection to the discredited Suharto era, his military record, particularly during Indonesia’s war in East Timor, his disregard for the rule of law, and a suspect human rights record.

Prabowo commanded the unit that captured and then killed East Timor’s legendary first prime minister, Nicolau Lobato, whose body was paraded before the press—to this day his souvenired severed head has not be returned to Timor for burial.

In addition, Prabowo has run for high office at least twice before but has never been elected to any position nor had legislative experience.

By contrast, his rivals are far less shopworn, a shortcoming Prabowo is trying to compensate for by appointing a much younger Indonesian as his running mate. The much younger Ganjar and Anies come from civil society, have strong academic, legislative and governance credentials, are not compromised by human rights accusations and were not involved in violence in East Timor.

They represent the fresh, post-reformasi, modern Indonesia that can showcase the best of Indonesia and position it to be the kind of leader the world needs.

Prabowo’s democratic deficits are referenced in the Indonesian media, particularly social media. Oddly, however, Indonesian and Australian media are largely silent on his record in East Timor. This omission serves Prabowo, but not the electorate. It leaves voters in the dark on an extended period that reveals a lot about his practices and values which, arguably, may characterise his presidency were he to be elected.

Indonesians don’t need to be told how to vote. But to exercise one’s democratic duty responsibly, voters should have access to the full picture in order to judge whether a candidate is fit and proper to lead their important nation and represent it to the world.

Based on evidence presented to it, East Timor’s truth and reconciliation commission, known as CAVR, concluded that the Indonesian military, and the Kopassus Special Forces in particular, were responsible for committing crimes against humanity and war crimes during Indonesia’s occupation of East Timor, from 1975 to 1999.

As a member and then a commander of Kopassus, Prabowo undertook at least four tours of duty in East Timor. These are referenced in a detailed background paper. They show Prabowo to have been anything but a bystander or bit player.

The CAVR report points to Prabowo’s repeated and shadowy deployments to East Timor. These in turn demonstrate his disregard for human rights, the rules of war (that we are hearing so much about in the current context of Israel’s offensive in Gaza), and on occasion insolence towards his own superiors.

Prabowo is also the subject of accusations of commanding massacres of as many as 200 civilians, mainly men, in the southern Timorese village of Kraras, an area now known as ‘The Valley of Widows’.

Prabowo first arrived in East Timor in 1976 soon after the invasion. He commanded the unit that captured and then killed East Timor’s legendary first prime minister, Nicolau Lobato, in 1978. Lobato’s body was paraded before the Indonesian and Western press, and to this day his souvenired severed head has not be returned to Timor for burial.

Happy days. Prabowo Subianto (in t-shirt) posing with militias and special forces soldiers in East Timor, during the illegal Indonesian occupation that was to last 24 long brutal years. (Photo: Susila Adib, Wikimedia)

In 1983, Prabowo bypassed a superior officer and undermined a peace process underway between moderate Indonesian military, and then resistance leader, now-president Xanana Gusmao. He is also the subject of accusations that same year of commanding massacres of as many as 200 civilians, mainly men, in the southern village of Kraras, an area now known as ‘The Valley of Widows’.

In 1985 Prabowo attended the commando training course in the U.S. at Fort Benning, the notorious U.S. Army’s ‘School of the Americas’.

Many of the Western-backed military dictators and coup leaders of the Cold War learnt their repressive soldiering there. As proxies of the U.S. military they went on to engage in human rights abuses including torture and forced disappearances in their own countries. Many of them served in the most repressive and undemocratic governments of the time.

Back in Indonesia, Prabowo was associated with the development of violent gangs and militias used to enforce repressive political policies.

In East Timor in the 1990s, Prabowo reportedly used Kopassus to train and direct the militias, and to create ‘ninja’ gangs to terrorise the Timorese population. He groomed a number of East Timor’s most violent militia leaders, such as Eurico Guterres, who would wreak so much havoc during the independence vote in 1999.

In West Papua in 1996, Prabowo led a Kopassus operation to free a group of international researchers who had been taken hostage by the West Papuan resistance in a bid for independence. With a partiality for the clandestine, a team of South African mercenaries from Executive Outcomes was also hired to advise and help conduct the operation.

Following the release of most of the captives, Kopassus and the mercenaries conducted brutal reprisal raids against villages believed to have supported the guerrillas, killing as many as 200. Despite official denials, allegations they used a white Red Cross helicopter as a subterfuge in the punitive raids were confirmed in an award-winning 1999 Four Corners program.

In West Papua after East Timor’s freedom was won, Prabowo’s protégé, Guterres, turned up to set up a pro-Indonesia militia group to combat the Papuan resistance. After creating years of killings and mayhem, Guterres returned to Indonesia.

In keeping with the proxy character of Prabowo’s unconventional warfare model, it was Guterres and not his creator Prabowo, who was tried, found guilty and sentenced to prison by an Indonesian court for crimes in East Timor.

Three subsequent U.S. presidents, and the Australian government, banned Prabowo from entry for violating human rights in both Indonesia and East Timor.

In Indonesia allegations of human rights abuses dogged Prabowo. He was reported to be involved in the rampages of violent gangs and the disappearance of student protestors in Jakarta in the period of the tumultuous transition away from the Suharto presidency in 1998. He fled the country after some believed he had failed in an attempt at a coup d’etat.

Following this, three subsequent U.S. presidents banned him from entry to the U.S. for violating human rights in both Indonesia and East Timor. It is believed a parallel visa ban was put in place in Australia banning him from entry at the same time. The ban was quietly dropped in Australia in 2014, and in the U.S. in 2020 after he was appointed as Defence Minister by President Jokowi.

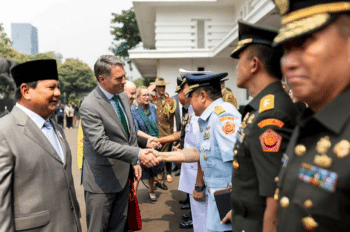

Mixing it with the generals. Indonesian Defence Minister, Prabowo Subianto, gives Australian Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Defence, Richard Marles, the meet-and-greet treatment with the generals in Jakarta, Indonesia, in June 2023. (Photo: Jay Cronin, Department of Defence)

Earlier this year, Canberra hosted Prabowo in Canberra for an Australia-Indonesia 2+2 Defence and Foreign Ministers’ meeting, and Defence Minister Richard Marles has visited Prabowo several times in Jakarta ‘to deepen defence cooperation under our Comprehensive Strategic Partnership’.

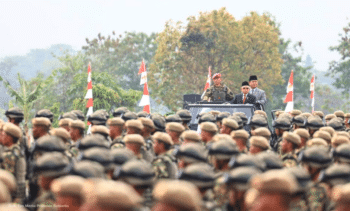

Even now in Indonesia, the fear of a return of violent militias remains. In October, Defence Minister Prabowo attended with President Jokowi the inauguration of 3,500 civilians as the first intake of a planned 25,000-strong new army reservists force, known as KOMCAD, the National Reserve Component.

The reserve recruits displayed varied skills including martial arts, disassembling guns, and firing cannons. The move to establish this civilian-military force has prompted civil society groups to lodge a Constitutional Court petition against the formation of KOMCAD, fearing a return to the history of violence by government-backed paramilitary groups.

For those prepared to look, the pattern is already clear. Prabowo is a man seen to be prepared to bend or ignore principle and to use his military and high-level connections in his interests.

Prabowo denies the accusations of human rights abuses. His self-defence includes claims that Indonesia only intervened to help settle an ‘internal conflict’ in East Timor. Were this true, one is entitled to observe that taking 24 years to sort out a so-called ‘internal conflict’ in a small country that, unlike Indonesia, did not receive any external military assistance, does not say much for the competence of the Indonesian military, the Kopassus ‘special forces’ or indeed Prabowo, one of its officers.

He also claims that he was not around at the time various violations were committed. It is true that he was not in East Timor in 1999—but those murderous militia groups were.

A blast from the dark past. Indonesian Defense Minister Prabowo Subianto (right) inspects civilian KOMCAD reservist troops at the KOPASSUS Special Forces Education and Training Center in Bandung. Prabowo stated the Republic of Indonesia mandates that every citizen has the obligation to participate in efforts to defend the country and to participate in efforts for national defence and security. (Photo: Indonesian Ministry of Defense)

These dogs of war were fully unleashed to attempt to destroy the independence referendum, giving rise to findings by four separate inquiries that gross human rights violations were again committed against East Timorese civilians in the presence of the international community.

Two of these human rights inquiries were Indonesian. Both found that the Indonesian military was responsible.

Civil society groups have lodged a Constitutional Court petition against the formation of the civilian-military force KOMCAD, fearing a return to the history of anti-democratic violence by government-backed paramilitary groups.

The joint Indonesian/Timor-Leste Commission for Truth and Friendship (CTF) concluded: ‘Pro-autonomy militia groups, TNI [Indonesian Armed Forces], the Indonesian civilian government, and Polri [Indonesian Police Force] must all bear institutional responsibility for gross human rights violations targeted against civilians’.

Prabowo was not named. But it is self-evident that the Indonesian military and other institutions mentioned by the CTF Commission did not suddenly emerge in East Timor in 1999 or only start behaving badly then—any more than the war between Palestine and Israel started on October 7 when Hamas launched an attack on targets in Israel.

As the CTF Commission observed: ‘The events of 1999 cannot be understood in isolation from the longer period of conflict that occurred in East Timor… The nature of the violence that occurred in 1999 was shaped by previous patterns of conflict’.

Prabowo was part of these ‘previous patterns of conflict’, including as one of their creators, as is detailed in my longer background paper. As such, he bears some of the shared responsibility for the fate of hundreds of civilians who endured ‘crimes against humanity’, a shocking term.

We are not talking allegations of traffic infringements or lapses in etiquette here. Unpacked, these crimes that offend the very essence of civilised humanity included starvation, forced displacement (including of children), rape, torture, killings, imprisonment and forced displacement.

The vast majority of Indonesians bear no responsibility for these excesses. As I have written elsewhere: ‘[Indonesia’s East Timor] campaign was an injustice to them as well.

‘Living under a dictatorship, they were not consulted or told the truth (and still aren’t). But as patriotic Indonesians they had to suffer the embarrassment of international condemnation for events beyond their control. Through no fault of their own, a beautiful people and country have been left diminished’.

A truth-telling process in Indonesia is needed. I say this acutely aware that a truth-telling exercise in consciousness-raising is only now commencing in Australia in relation to the impact of our colonial past on Indigenous peoples.

The deeply regrettable downside of this overdue process in Indonesia is that a person many believe has demonstrated a disregard for the rule of law, of both the domestic and international kind, and is regarded by many as a war criminal, may be elected Indonesia’s next president.

Pat Walsh is a human rights advocate and author. He is co-founder of ‘Inside Indonesia’ magazine, and was an adviser to East Timor’s Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation Commission (Comissão de Acolhimento, Verdade e Reconciliação—CAVR), and its successor bodies. The ‘Backgrounder on Prabowo Subianto’ can be found on his website—www.patwalsh.net