A guard working at a Hudson Valley prison pummeled a 19-year-old shackled by the legs to a restraint chair. An officer at a facility near the Canadian border denied food to a man in solitary confinement 13 times over a week. Outside Albany, a guard told a prisoner, “That’s how you get dumped on your fucking head,” then smashed his head into a wall.

Each time, New York state officials fired the guards. Each time, they appealed. Each time, private arbitrators gave the officers their jobs back.

Between 2010 and 2022, arbitrators reinstated three out of every four guards fired for abuse or covering it up, according to a review by The Marshall Project of 136 cases. The decisions the outside arbitrators wrote heavily favored prison guards, even in the face of strong evidence against them.

Just two arbitrators handled about half of these cases, the review found. Arbitrators often dismissed prisoners’ testimony as unreliable and criticized the state for putting on weak cases, according to a review of disciplinary records. Among the cases in which arbitrators upheld the firings of officers, a majority came after coworkers contradicted the accused guard.

In effect, arbitrators–typically private lawyers–can overrule personnel decisions made by the corrections department’s senior leadership, including the commissioner appointed by the governor.

Former New York state corrections Commissioner Brian Fischer said arbitration is “a crazy system” that doesn’t benefit the public. “The employee should be terminated, the inmate should not be abused,” he said.

And yet we let it go on and on.

Current and former arbitrators say the system has a limited role: to protect a worker from a supervisor’s unfair decision, based on the evidence. “Those laws are not written to protect management,” said James Cooper, who decided New York prison guard cases for about 30 years.

Those laws are designed to protect the employees.

As The Marshall Project and The New York Times previously reported, the state almost never succeeds in firing guards. Experts say this helps sustain a culture of cover-ups among corrections officers who falsify reports and send beating victims to solitary confinement.

New York’s corrections department tried to fire Frank Nowicki, a guard at Attica prison, pictured here. He was accused of participating in a group beating of a prisoner, but an arbitrator returned him to work. (Photo: HEATHER AINSWORTH FOR THE MARSHALL PROJECT)

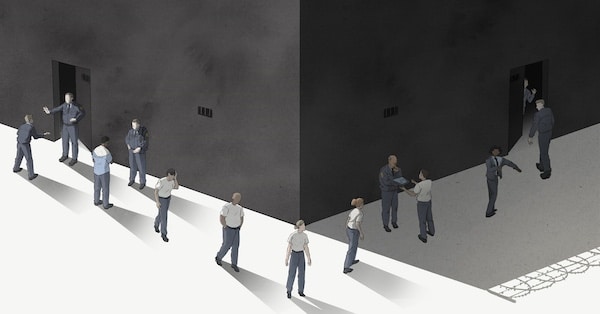

Arbitration loosely resembles a trial. The prison agency investigates misconduct and presents evidence at a hearing, which can last days, to defend its decision to fire a staffer. The state and the guards’ union call officers, prisoners and experts as witnesses before the arbitrator, whose role resembles that of a judge. Both sides help select the arbitrator.

Arbitrators typically make rulings based on the preponderance of the evidence–meaning the misconduct was more likely than not to have occurred. But in practice, The Marshall Project analysis found, they often didn’t fire guards unless there was overwhelming evidence. Nearly every abuse case in which a guard’s firing was upheld relied on the statements of coworkers, video or DNA evidence, according to the review. There was one exception, and in that case, eight prisoners testified against the officer.

“Unfortunately, the department as a whole has been very comfortable with lying on reports for years,” said John Ginnitti, who spent 15 years as an internal investigator after 19 years as a prison guard.

The rarity of firings sends the message to officers that misbehavior imposes little risk or cost.

“Hey, this strategy works for us,” Ginnitti said.

Why would we change it?

In an email response to written questions, a spokesman for the corrections department wrote that the agency “does not speak for or represent disciplinary arbitrators, as they are independent third parties.”

The prison guards union president said in a statement that while his organization takes reports of abuse seriously, it has a duty to defend members from any allegations.

“Other than successfully defending our members a majority of the time in the cases cited, we have no influence over the decision the arbitrator makes,” said Chris Summers of the New York State Correctional Officers and Police Benevolent Association.

It is a system that is independent, fair and just.

The limited but growing number of body and wall cameras in many New York prisons means that video evidence was often unavailable in the cases reviewed. In its statement to The Marshall Project, the department pointed out that it has spent hundreds of millions in recent years installing more cameras in prisons and expanding its body camera program.

Meanwhile, cracks in the blue wall are rare. Officers who report a colleague’s wrongdoing can face harassment and threats on the job.

Cody Mackey was a trainee at Five Points prison in the Finger Lakes region in 2016 when he reported misconduct he said he witnessed, records show. A prisoner had thrown clear liquid at him and two other guards. Mackey went into a staff bathroom to remove his shirt as evidence and found one of the officers urinating on his own and the second guard’s uniforms–they were trying to frame the prisoner. Video captured the guards discussing the scheme, according to state records. Prison officials fired them.

The guards appealed. Mackey’s testimony and a DNA analysis of the urine convinced the arbitrator to fire the guard who urinated and a sergeant who covered it up; the other officer was suspended for 9 months. By then, prison managers had removed Mackey from Five Points over concerns for his safety. He was transferred to another prison, where, on his first day, two correctional officers called him a rat to his face. Someone took to the public announcement system to say, “Things are going to be different here than at Five Points,” according to arbitration records. He resigned at the end of his shift.

The prison department spokesman said employees who retaliate against staff for reporting wrongdoing are investigated and held accountable.

Mackey said the FBI opened an investigation into additional threats made against him on Facebook and elsewhere.

“I didn’t get union protection,” he said.

They’re protecting the bad COs.

Shortly after two guards said they used force to subdue a prisoner who attacked them at Wende prison, near Buffalo, in 2014, investigators received a complaint that the prisoner had been assaulted.

In their reports, guards David Nixon and Richard Mazzola claimed that they punched the prisoner several times in the side and shoulder. But the man had a boot-shaped bruise on his back, and he said that officers had broken three of his teeth, according to arbitration records.

The prison agency fired the guards, who appealed. When the case went before an arbitrator, doctors for both the union and the state testified that the prisoner’s wounds were consistent with a baton strike and a boot-heel stomp.

The two guards testified that they used force to gain control of a prisoner who had attacked Mazzola. They stuck with what they wrote in their use of force reports, which did not account for the prisoner’s serious injuries.

Arbitrator Samuel Butto ruled in 2016 that the officers were guilty of lying in their reports and that they deserved severe penalties. But he still reversed their firings, citing their excellent work histories. He ordered them back on the job after a 12-month suspension without pay.

In an emailed response, Butto declined to discuss individual cases. “I have always approached each case with all its complexities objectively, and reviewed my decisions with great care to preserve or restore the rights of all concerned,” Butto wrote.

Nixon did not respond to a request for comment; Mazzola declined. Acting as his own lawyer, the prisoner sued the guards for excessive use of force; in 2020, the state paid him $9,200 to settle the case.

A good work history was one of the most common reasons arbitrators cited in reinstating fired officers. This held true even in cases where the state presented video or other strong evidence of mistreatment.

In one case, video captured an officer threatening to “dump” a prisoner before slamming his head into a wall, according to arbitration records. The state argued that video evidence proved the guard used excessive force and needed to be fired. But the arbitrator, Timothy Taylor, was not convinced the head slam was intentional–it could have been an “inartful attempt to bring the inmate under control,” he wrote. Taylor found the officer not guilty.

Reached by phone, Taylor declined to comment, and he did not respond to detailed written questions.

Of the more than 100 officers that arbitrators returned to work, just over half were found guilty of at least some of the charges and had their penalties reduced, usually to a suspension. The others were found not guilty of all charges.

In about half of the reinstatements, arbitrators said the state hadn’t provided enough evidence to prove its case. Arbitrators also cited flawed or incomplete investigations by the state, such as failing to interview key witnesses. A spokesman said that the corrections department considers flawed investigations to be a rare occurrence, and that after a case concludes, state officials meet internally “to ensure we address any concerns noted by the arbitrator in future investigations.”

At the same time, prison abuse cases can be difficult to prove, said Cooper, the former arbitrator. The abuse takes place in a closed environment where guards cover for each other and a prisoner’s credibility can be undermined by their criminal records and inconsistencies in their stories. “You’ve got lousy witnesses with the prisoners, you’ve got liars with the officers, and physical evidence is hard to come by,” Cooper said.

Cases often come down to the guards’ words versus the prisoners. Arbitrators did not find the accounts of prisoners credible in a third of the reinstatements The Marshall Project reviewed.

Police departments also frequently use arbitration, drawing scrutiny in recent years. Arbitrators have ordered police leaders to rehire officers accused of serious misconduct, including unjustified fatal shootings, sexual assault and drug trafficking.

Arbitrators returned police to work in about half of excessive force cases, according to Stephen Rushin, a law professor at Loyola University Chicago who has analyzed hundreds of arbitration decisions nationwide. That’s far less than the three-quarters of fired prison guards who have been reinstated in New York.

In recent years, some states have changed laws governing arbitration for police officers. Oregon now limits the power of arbitrators to reduce the punishment handed down by management. Minnesota has a new law that prevents unions and police departments from selecting arbitrators.

New York correctional officers gained the right to arbitration as the final step in a guard’s firing in 1972. In the decades since, the guards’ union has successfully fought to keep arbitration, despite efforts by the Legislature and governor to change the process. In 2019, officials negotiated a contract change that created three-person arbitration panels for the most serious cases, hoping to give the state more power to fire guards. Each panel would have representatives from both the union and the state as well as an independent arbitrator appointed on a rotating basis.

Four years on, the department and the union have never used the new panels. The union contract expired at the end of March but remains in effect while Gov. Kathy Hochul’s office negotiates a new agreement.

The reliance on arbitrators to resolve disciplinary disputes exists in most union contracts, said Harry C. Katz, a professor of collective bargaining at Cornell University. Management typically fails to fire employees because it puts on poor cases, he said.

Public agencies like to blame arbitrators, and that may be true in some cases, but officials seldom acknowledge their own agencies’ failings, Katz said.

“If management really doesn’t like how it’s working, negotiate a different contract,” he said.

Yeah, it’s difficult, but not impossible.

When New York union representatives appeal a guard’s firing, they and prison officials choose the arbitrator by ranking a list of candidates.

The Marshall Project requested these selection records, but the agency that administers state arbitrations insisted they are secret.

Corrections department records show that some arbitrators get picked much more often than others. Butto and Taylor were selected most, handling half of the abuse cases reviewed. The other half of the cases were split among 19 arbitrators.

Dan Nielsen, former president of the National Academy of Arbitrators, said it’s not unusual for certain arbitrators to be selected more than others. It’s a reflection of the confidence both sides have in them, he said.

If there’s someone who is mutually acceptable, that’s the person who gets the case.

Butto and Taylor took different paths to full-time arbitration work. Butto spent 10 years at the corrections department and represented the state at arbitration hearings, trying to fire guards for misconduct. Taylor, by contrast, worked for more than two decades as a lawyer representing New York’s teachers’ union.

Arbitrator Timothy Taylor upheld the termination of a lieutenant at Great Meadow Correctional Facility in New York, pictured here, in 2020, but determined that almost half of the officers who appeared before him in other cases were not guilty. (Photo: JOHN CARL D’ANNIBALE/TIMES UNION)

Each man upheld the firings of guards about 20% of the time, according to The Marshall Project’s analysis. Taylor terminated a lieutenant at Great Meadow prison in the Adirondacks who had 22 years of outstanding job evaluations but a history of using excessive force. Butto fired an officer for a beatdown and cover-up, partly because the guard didn’t testify on his own behalf or express remorse.

But from there, their decisions about abuse cases diverged.

Taylor determined that almost half of the officers who appeared before him were not guilty, reasoning that the state’s cases were too weak to prove the allegations, according to the review. In contrast, Butto found most officers were guilty of at least some of the abuse-related charges. But rather than fire them, he decided the majority should instead be suspended, typically citing an officer’s good work history as a mitigating factor.

Both are experienced arbitrators. Butto is a member of the Labor and Employment Relations Association and serves on several arbitration panels, according to his resume. Taylor was the first person of color to chair the labor and employment law section of the New York State Bar Association.

They have both decided cases for a variety of New York agencies. For the state prison department, Taylor not only presides over disciplinary disputes, but also resolves disagreements about the union’s contract.

The payment for a prison arbitration case is limited to $1,200 per day, split between the union and the state, but the pay can be substantial. Arbitrators have billed the union and the state tens of thousands of dollars for a single excessive-force case, according to invoice records.

In some cases, arbitrators have returned accused officers to work even when prisoners suffered severe injuries.

The prison agency tried to fire an Attica guard, Frank Nowicki, after accusing him of participating in a group beating of a prisoner who needed 13 staples to close two head wounds. At the arbitration hearing, a neurologist testified that the wounds were consistent with baton strikes. The union’s expert, the warden of Attica, cited his 35 years of prison experience and testified that he did not believe the wounds were caused by a baton.

Taylor found the neurologist’s testimony lacking. “Although a very impressive witness,” Taylor wrote, he “is not an expert on baton strikes or what injuries caused by batons look like.”

The arbitrator declared the prisoner not credible for making inconsistent statements in different reports and wrote that the state failed to prove its case. He found Nowicki not guilty, and returned him to work.

Three years later, the state paid $45,000 to settle a lawsuit the prisoner filed against Nowicki and other officers for the physical and emotional wounds he suffered. Nowicki, who did not respond to requests for comment, denied the allegation of abuse during the arbitration and in the lawsuit.

Ginnitti, the retired investigator who was in charge of the Nowicki investigation, said arbitrators have a financial interest that discourages them from firing guards.

An arbitrator “knows darn sure that if he fires too many people, or somebody that the union feels he shouldn’t, he’s never getting picked for arbitration again,” Ginnitti said.

This article was published in partnership with Albany Times Union, Investigative Post and New York Focus.

Alysia Santo is a staff writer. She has investigated criminal justice issues including for-profit prisoner transportation, the bail industry, victim compensation and the sexual abuse of people behind bars. Her reporting has spurred state and federal investigations, and was awarded Harvard’s Goldsmith Prize for Investigative Reporting in 2021. She is also a three-time finalist for the Livingston Award and was twice named runner-up for the John Jay College/H.F. Guggenheim Prize for Excellence in Criminal Justice Reporting.

Joseph Neff is a staff writer who has investigated wrongful convictions, prosecutorial and police misconduct, probation, cash bail and forensic ‘science’. He was a Pulitzer finalist and has won the Goldsmith, RFK, MOLLY, SPJ’s Sigma Delta Chi, Gerald Loeb, Michael Kelly and other awards. He previously worked at The News & Observer (Raleigh) and The Associated Press.