Richard Clarke introduces some of the main Marxist insights into the nature and value of art, and its links to political and economic realities.

Most Marxists would say that the value of a work of art such as a painting, or the pleasure they get from it—in its original or as a reproduction—is above all else an individual matter, not something that ‘experts’ (Marxist or otherwise) can or should pronounce upon. At the same time experts can enhance that pleasure, for example by explaining the technique and methodology of the composition of a painting. Again, this is no more the exclusive province of a Marxist than (for example) a commentary on the technical skills embodied in the design or manufacture of a washing machine.

However a Marxist approach may help to deepen the appreciation or understanding of an art work by revealing the historical context of its production and the relation of a work of art or of an artist to society. Art, just as any other human activity, is always created within a specific social and historical context, and this will impact on the art work itself. This is why Marxists argue that one can only begin fully to appreciate and understand a work of art by examining it in relation to the conditions of its creation.

Here a fruitful starting point for discussion is a materialist view—looking at the production and consumption of art, the position of artists in relation to different classes, and the conflicts embodied in a work of art and in the history of which it is a part. For example, Ernst Fischer’s seminal essay The Necessity of Art (1959) is a Marxist exposition of the central social function of art, from its origins in magic ritual through organised religion to its varied and contradictory roles within capitalism and its potential in building socialism.

The Marxist art critic John Berger in his Ways of Seeing (a 1972 four-part television series, later adapted into a book, Ways of Seeing) was hailed by many people for helping to deepen their understanding of art. Berger argued that it was impossible to view a reproduction of ‘old masters’ (generally paintings by European artists before 1800) in the way they were seen at the time of their production; that the female nude was an abstraction and distortion of reality, reflecting contemporary male ideals; that an oil painting was often a means of reflecting the status of an artist’s patron; and that contemporary advertising utilises the skills of artists and the latest artistic techniques merely to sell things for consumption in a capitalist market.

Berger’s work remains controversial and has been revisited many times, particularly since his death in January 2017. Many have argued that he over-simplifies and that he incorporates the deeper perceptions of others such as Walter Benjamin, working at the interface between Marxism and cultural theory. Some have asked (for example) why there is no reference to feminist theorists in Berger’s chapter on the ‘male gaze’. However Berger’s work needs to be seen in context as a polemical response to the ‘great artists’ approach which characterises much establishment art history and ‘art appreciation’ typified by Kenneth Clark’s (1969) Civilisation television series.

What is clear is that cultural expression (art, lower case) is characteristic of all human societies and that while art and society are intimately connected, the former is not merely a passive reflection of the latter. The relationship is a dialectical one. As Marx declared in A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy:

The object of art, like any other product, creates an artistic and beauty-enjoying public. Production thus produces not only an object for the individual, but also an individual for the object.

A distinction is often made between the performing arts (including music, theatre, and dance) and the visual arts (such as drawing, painting, photography, film and video). Performing arts are of their nature ephemeral, and as Robert Wyatt, the communist percussionist of the ‘60s psychedelic rock group Soft Machine, declared, ‘different every time’. The performance is the initial product, although it may be recorded, reproduced and subsequently sold.

‘Art’ (as in painting, on canvas) is sometimes presented as the highest point in the development of ‘civilised’ culture. Jean Gimpel, an historian, diamond dealer, and expert in art forgery, attacked the concept of ‘high art’ in his book The Cult of Art (subtitled Against Art and Artists). He argued that the concept of Art—especially oil paintings, on transportable framed canvas—is specifically a product of capitalism, personified in the Florentine artist Giotto ‘the first bourgeois painter’ of the Renaissance and his successors.

Under the patronage of the Medici and other nouveau riche Italian patrician families, the ‘artisan’ workmanship of frescos on church walls or decorated altarpiece was superseded by the movable (and marketable) canvas. In short, it was commodified. ‘People no longer wanted a ‘Madonna’ or a ‘Descent from the Cross’ but a Leonardo da Vinci, a Michelangelo or a Bellini.’ The cult of art and the artist was born.

Yet it was not until the eighteenth century that the distinction between ‘artisan’ and ‘artist’ became fixed. Even today people can be heard asking—of everything from the Lascaux cave paintings to some suburban topiary–‘but is it Art?’ High art of course also produced its supposed antithesis—the artist in his garret (women artists were to a degree excluded from the equation), suffering, sometimes starving in the cause of art unless they are lucky enough to be ‘discovered’, often only after death. With capitalism, for the first time the artist became a ‘free’ artist, a ‘free’ personality, free to the point of absurdity, of icy loneliness. Art became an occupation that was half-romantic, half-commercial.

Dire Straits’ ‘In The Gallery’ is a song about the conversion of use-value (the worth the artist or her audience see in an art work or the pleasure they get from it) into exchange value. Harry is an ex-miner and a sculptor, ‘ignored by all the trendy boys in London’ until after he dies, when, suddenly, he is ‘discovered’ (too late for Harry, of course)—the vultures descend to make profit from his work.

In The Gallery

Don Mclean’s ‘Starry Starry Night’ carries a similar message. The principal difference (beyond the tempo of the songs) is that Harry is politically engaged, very much of this world whereas tormented Vincent (Van Gogh) was ‘out of it’—unlike his post-impressionist erstwhile friend, Paul Gauguin, who asked his agent what ‘the stupid buying public’ would pay most for and then adjusted his output accordingly.

Vincent (Starry Starry Night)

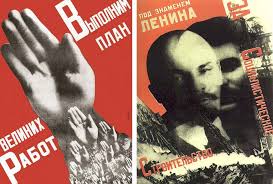

Irrespective of their recognition or fame, art and artists are frequently presented as apart from, sometimes above, society. For Marxists it is clear that the arts and artists are an integral part of society. In terms of aesthetics and policy however, Marxists would suggest caution—the history of art within socialism is a mixed one. The early flowering of post-revolutionary Soviet avant-garde art is well known. Constructivism strived to put art at the service of the people. The subsequent rise of socialist realism as ‘official’ art was an attempt to make art more accessible (and it existed alongside a flourishing variety of unofficial art forms).

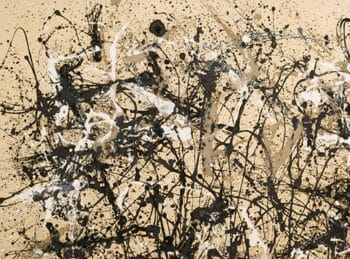

In the United States modern art was promoted as a weapon in a cultural cold war with the Soviet Union and its ‘socialist realist’ art forms. In the 1950s and 1960s, through the Congress for Cultural Freedom, the Farfield Foundation, and other covers, the CIA secretly promoted the work of American abstract expressionist artists—including Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning and Mark Rothko—in order to demonstrate the supposed intellectual freedom and cultural creativity of the U.S. against the ideological conformity of Soviet art.

Jackson Pollock, Autumn Rhythm (Number 30)

Even when art is oppositional, capitalism has an uncanny knack of appropriating it. The Royal Academy’s 2017 exhibition of Russian revolutionary art was accompanied by vicious and ignorant curating—presumably to disabuse any who might otherwise have been inspired by the works on display. Banksy’s graffiti, a determinedly uncommercial form of art ‘for the people’ (maybe a modern equivalent of the Lascaux cave paintings?) is now ‘in the gallery’—decidedly a collector’s item with a price tag to match. Another (dead) graffiti artist, Jean-Michel Basquiat’s 1981 depiction of a skull was auctioned in May this year for more than $100 million. Banksy’s own comment on this is conveyed on a wall of the Barbican where a posthumous exhibition of Basquiat’s work runs until January 2018 (admission £16). City of London officials are currently considering whether (and how) this fresh graffiti might be preserved.

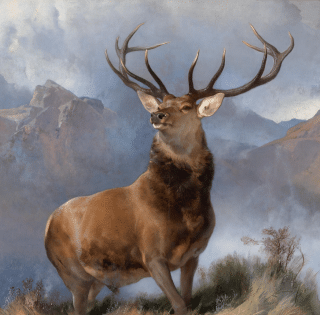

Within capitalism, as its crisis deepens, ‘high art’ (provided it is portable, saleable, in a word, alienable) is—next to land and other property—one of the best investments that there is. A recent example is Sir Edwin Landseer’s ‘Monarch of the Glen’, ‘saved’ for the nation in March 2017 at a cost of £4 million, through a fund raising exercise to pay its owner, Diageo. This multinational drinks conglomerate (profits last year £3 billion on net sales of £10.8bn, 15% up on the previous year; CEO Ivan Menezes’ salary £4.4m) graciously agreed to accept just half of the paintings ‘estimated value’ of £8 million. More than half of this money came from the National Lottery—itself sometimes described as a ‘hidden tax on the poor’.

Edwin Landseer,The Monarch of the Glen

Gaugin’s Nafea Faa Ipoipo? (‘When Will You Marry’?), painted in 1882 and, like his others, presenting a romanticised view of Tahiti, sold for $300 million in 2015–just topped by de Kooning’s Interchange the following year. A 24ct gold bracelet, designed by Ai Weiwei, the Chinese ‘dissident’ and ‘champion of democracy’, inspired by the 2008 Sichuan earthquake (the deadliest earthquake ever, 90,000 dead, between 5 and 11 million homeless) sells for a modest £45,500 from Elisabetta Cipriani, (ElisabettaCipriani). The majority of artists and their artworks of course, never reach such dizzy heights.

The role of the artist in society remains a controversial subject. In the meantime it is clear that art and artists can and do play a vital role and that artistic freedom and license are crucial. Perhaps a good model is that followed in the former Yugoslavia and other socialist countries (as today in Cuba). Artists were not paid or employed as such by the state, although the arts in general were and are given generous state support. As in capitalist countries artists had to make their living through commissions, though these would be more likely to come from community associations, trades unions, local councils and the like, rather than from wealthy patrons or investors. Many would have to supplement their incomes by teaching, or by doing other jobs. But their social position was recognised and their social security contributions were paid so that on ill-health or retirement they would not suffer.

In both the appreciation, understanding and, indeed, production of art, and whether you love or loathe his own designs, one assertion that all socialists would surely agree with is that of the communist William Morris, who declared ‘I do not want art for a few; any more than education for a few; or freedom for a few…’, (Hopes and fears for art). What is certain is that art—of all types—can enrich our lives. It can also be galvanising, a force for social progress. But it is also clear that art that is subject to capitalist market forces involves a chronic distortion of the artistic product and process in which art works are valued for their price tag rather than their intrinsic quality. A Marxist approach can deepen our understanding of art provided that we avoid dogmatism and accept that this is an area of debate—one to which we can all contribute.