In April 2015, the Pacific Standard (RIP to yet another quality outlet shuttered) published a defense of rent control—with an opening salvo declaring it dead. New York tenant organizers would go on to win small, highly technical improvements to their rent regulation system a little later that year, but in the broad strokes, the Standard’s appraisal at the time wasn’t wrong. Localized systems in New York, California, and New Jersey were riddled with pro-landlord loopholes, while 31 states had instituted outright rent control bans, most at the behest of a shadowy neo-con organization. Diego Morales, an organizer with the Lift the Ban Coalition, remembered rent control as a “taboo” topic inside the halls of the Illinois Capitol, unmentionable because of how resoundingly hated it was by economists and policy experts.

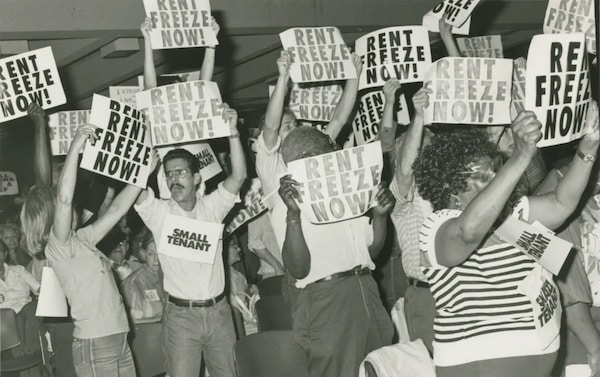

Just eight years later, rent control is back from the dead with a vengeance, with serious organizing campaigns underway in at least 15 states. There are campaigns to strengthen and expand existing rent regulation statutes in coastal cities, to lift statewide pre-emption laws in the Midwest, and to instate local control of rents in Western and even Southern states. A lot has changed since 2015: the U.S. has been through an aspirationally fascist presidency, a global pandemic, and a national rebellion for racial justice. After multiple failures in the housing system, more people are renting than ever, and those who do rent are often in a significantly more precarious position. Both tenant organizers and landlord lobbyists have adapted their strategies to our current political moment, with high-profile victories in some places (St. Paul and Oregon) matched by setbacks in others (Minneapolis, Florida).

How did rent control come back from the dead so quickly?

Rent control has been around for as long as the landlord. Since antiquity it has served as a tool for limiting land speculation, especially during economic shocks. In Rome, beginning in 40 B.C.E., in the wake of civil war, a debt crisis, and political turmoil, the government instituted a temporary rent cap and a cancellation of rent for one year. Likewise, imperial China under the Song Dynasty began to use rent controls around the year 1000 A.D. to curb speculation and stabilize the rental market. Examples of temporary rent control measures can be found in dozens of late medieval cities, especially during times of armed conflict, pandemics, or great fires.

Rent control in its modern incarnation, argues historian Jo Guldi, can be traced back to the 1881 Land Court of Ireland; Guldi describes it as an anti-British, anti-colonial measure to “reverse the racism of an economy established under empire”—an empire that had stolen Irish land and banned Catholic landownership. Unlike earlier iterations, the Irish system was a permanent response to inequities within the housing market, rather than a temporary response to an economic shock. The law owed as much to economically crippling rent strikes by tenant farmers as to the anti-colonial Irish intelligensia, who had developed the concept of a “fair rent” system. The latter aimed to replace an extractive real estate market with a “quantifiable and objective” system of land valuation that took tenant farmers’ productive use of leased land into account. To operate, the Land Court depended on two key factors: a new class of Irish civil servants trained to collect data in a systematic fashion, and the public acceptance and legitimacy of a new judicial body that could adjudicate between tenants and landlords.

Establishing an analogous fair rent system would later become a goal shared by anti-colonial tenant farmer organizers in farther reaches of the British empire, like India and New Zealand. Labor organizers in industrialized English and Scottish cities had also began to agitate for rent control at the turn of the century. But it was not until the outbreak of World War I that England saw its first comprehensive rent control act, which limited rent increases, provided urban tenants with good-cause eviction protections, and regulated warehousing of vacant units.

The economic impact of World War I, paired with ongoing radical labor organizing in the U.S., also paved the way for the first two U.S. rent control laws. In New York, radical agitation around worsening living conditions, including a rent strike organized by Jewish textile workers that swelled to 10,000 strong, pushed the New York State legislature to create a court-based rent arbitration process in 1920. A year earlier, Washington D.C. created a new judicial body to determine fair rents and resolve conflicts between tenants and landlords. D.C.’s law was immediately challenged in the Supreme Court, but it withstood the legal assault. Like the Irish Land Court, these early U.S. rent control systems depended on the combination of the perceived neutrality of judicial bodies and expert data analysis to justify their intervention in the real estate market. Yet as a result of pressure from landlords, both systems were quickly phased out within just a few years.

While rent control was only applied to a limited extent in the U.S. of the 1920s, nations across the world contended with the fall of empires, wars, colonialism, and disease by experimenting with rent-regulating laws. World War II changed the U.S. relationship to rent control; the federal government taking a highly interventionist role in the economy overall through the Office of Price Administration (OPA). In parallel, the federal government enacted a comprehensive rent control standard to prevent “rent profiteering,” which would “undermine civilian morale.”

After the war, the federal government delegated the responsibility over rent regulation to the states. The majority, with a couple of exceptions (New York among them), chose to phase it out. The second Red Scare was underway, and opponents of rent control were quick to decry rent control as a key part of a communist conspiracy to overthrow the U.S. A state representative in Tennessee testified that an effort to continue controlling rents in 1949 “had its origin in the minds of men who hate our free institutions. It is shrewdly drafted and designed to give the Government power over the property of our citizens, and thereby give it power over the lives of our people… The act is more Russian than it is American… It is un-American.”

After that die-off of U.S. rent control in the late-1940s, it wasn’t until the 1970s that local tenant organizing campaigns managed, in some areas, to resurrect it. A new wave of laws went into effect in New York City and its suburbs, as well as 13 localities in California, five in Massachusetts, and 120 in New Jersey. Unfortunately, this moment was equally short-lived. As Rebecca Burns wrote in In These Times,

real estate interests quickly organized a powerful countermovement that pushed through a slew of so-called preemption laws, which allow states to overturn or prevent municipal-level progressive policy, beginning in the 1980s.

The anti-rent control push was part and parcel of a revanchist political turn that championed deregulation, austerity, and carceral solutions over measures that not only were of no benefit to marginalized people, but also dehumanized and actively harmed them. As the social safety net frayed, rent control became a convenient scapegoat for declining housing conditions, increased homelessness, and even increases in street crime.

This belief permeated deeply into American culture, helped along by real estate dollars. For example, Burns found that the California Association of Realtors spent $14.2 million to fight rent control in the mid-1980s. Still, the Supreme Court affirmed its constitutionality in 1986, and a nationwide tenant mobilization pushed back Ronald Reagan’s attempt to cut off community development funds to states without rent control bans.

Over time, 31 states passed rent control preemption laws, often using a model law written by the highly influential American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC). Oregon effectively ended its preemption law in 2019 with the passage of SB 608, a statewide rent control ordinance. Five more states have de facto rent control bans. These are Dillan’s Rule states, which require local governments to seek explicit permission from the state legislature to perform many types of functions, including regulating rents. In these five states, no localities have sought to enact rent control policies, because they would immediately be preempted by rightist state governments.

ALEC has been an enduring villain for rent control and innumerable other campaigns. In a deep history of the rent control ban in Illinois, Maya Dukmasova described ALEC as a platform where “conservative causes ranging from abortion restriction to rolling back environmental regulations to fighting labor unions to rent control get pitched to state legislators or find sympathetic allies among moneyed special-interest leaders.” The sanctity of property law and fear-mongering about state overreach, echoing earlier red-baiting rhetoric, were central to the success of these ALEC rent control bans.

It should come as little surprise that traditionally liberal states were not immune: Massachusetts banned rent control in 1994. And although California and New York did not pass outright bans (despite the best efforts of landlord lobbies), a mounting number of loopholes were incorporated into the policies, weakening them significantly. Some states, like Illinois and Tennessee did not pass bans until the late 1990s. By that time, a strong association between rent control and vaguely defined urban maladies had calcified in the minds of policymakers. Unproven and under-researched anti-rent control policy truisms were propped up by economics textbooks and self-appointed policy experts alike.

The fallout from such major policy changes, of course, only comes into focus after considerable time has elapsed, often outliving the careers of the politicians that instituted them. By 2008, as the mortgage market collapsed, the cumulative impacts of more than two decades of Reaganite financial and housing deregulation and social safety net cuts were finally coming to a head. The collapse created a feeding frenzy for investors, who, in the wake of the crisis, scooped up real estate across the U.S.—often at a deep discount, and while enjoying the benefit of financial support from the federal government.

In New York City, they bought 100,000 low-rent units. In Atlanta, Orlando, and other sunbelt metro areas, investors scooped up foreclosed single family homes with the help of a federal program and turned them into rentals. In Utah and New Hampshire, investors used federally backed mortgages to buy out manufactured home communities. While their methods varied according to local legal frameworks and political conditions, the new corporate landlords instituted business models that squeezed profit out of their newly acquired assets: milking properties by withdrawing services and rising rents, passing costs for water and pest management on to the tenants, and/or over-leveraging and pulling out equity. More Americans were renting then ever before—and more began to struggle under the mounting toll of austerity.

Rising rents, stagnating wages, and the indignity of corporate bailouts, paired with ever-deeper cuts for social services in the wake of the mortgage crisis, laid the groundwork for a new era of left organizing in the U.S.—one less encumbered by both New Left factionalism and a fear of red-baiting. As organizers looked around for day-to-day issues impacting regular people, rents almost always rose to the top.

Controlling rents just made intuitive sense to Ritti Singh, who organized with the City-Wide Tenant Union of Rochester, a city in upstate New York that is not covered by the state’s rent stabilization law. Said Singh,

Telling tenants that rents don’t need to rise every year is really easy for door-knocking… it gets back to basics that aren’t super wonky.

As tenant leaders and organizers once again resurrected rent control as a legitimate goal, the left experienced, in the words of Sumathy Kumar, an organizer with New York’s Housing Justice for All campaign, an “electoral moment.” Rent control became a popular plank for city and state office candidates running with support from organizations like Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) and the Working Families Party. Left candidates gained legitimacy from supporting issues important to tenants, while rent control gained legitimacy as a very serious housing policy by crossing over into the electoral realm, including a big boost from Bernie Sanders’s promise of a national rent control system.

The professional class, which has been an important validator of rent control systems since the earliest Irish efforts in the 1880s, did indeed register these larger social and political shifts, if only incrementally. While deregulatory brain worms continue to muddle the minds of many an economist, Ruth Gourevitch, who has worked as a policy advisor in the federal government and now works with the Climate + Community Project, saw the political moment open up policy possibilities to see the “end user of our policy responses as renters, not landlords.” It allowed policy people to become unmired from the kinds of complex tax incentive schemes that have defined housing policy since Reagan’s era.

At the same time, the slow relegitimization of rent control did not translate into an immediate instantiation of tenant power in the political sphere. In 2015, when Richmond and Mountain View became the first localities in decades to opt into California’s rent control system, landlords counter-organized. In 2018, they ended up spending nearly $80 million to protect Costa-Hawkins, a 1995 law that severely weakened the state’s rent control system. In 2017, efforts to lift ALEC rent control bans in Illinois and Colorado failed. The same year, landlords also outspent tenants in local referenda—like the one in Portland, Maine—and won.

Still, two big state-level victories in 2019 did help shift the tide a bit. In Oregon, a coalition of labor, housing, and racial justice groups helped pass a rent control bill, which prohibited no-cause evictions and rent increases higher than 7 percent above inflation. Significantly, this was the first new statewide rent statute since World War II—a resounding victory and precedent-setting development in the rent control fight. Later that year, after decades of chipping away at mid-1990s anti-tenant loopholes, Housing Justice for All, a statewide coalition in New York, strengthened and expanded the state’s rent stabilization system.

The pandemic, in tandem with the largest mobilization for racial justice in U.S. history, further put the housing question into the limelight. Nowhere was this more apparent than in St. Paul, Minnesota, where organizers collected signatures to get a rent control referendum on the ballot during the uprisings and demonstrations over the murder of George Floyd in neighboring Minneapolis. As they knocked on doors and spoke with local tenants, tenant organizers often found opportunities to point out the links between state violence and the housing precarity experienced by Black residents of the Twin Cities.

Tram Hoang, who led the Keep St. Paul Home campaign, explained that the coalition first built out its structure and working relationships during an earlier campaign in 2017 that had sought to institute a less robust set of tenant protections. When that effort succeeded, the city council rolled it back almost immediately—because of a legal challenge from landlords. The coalition, recognizing the apparent spinelessness of their city council, worked to out-organize the landlords by appealing directly to voters in a referendum. Referenda can be a risky undertaking, since heavy spending by political opponents can easily sway public opinion. But ultimately, in 2021, the coalition’s deep relationships in St. Paul and its effective organizing made it possible to push through the most comprehensive rent control law in the U.S.

Around the same time, the local DSA chapter in Portland, Maine launched a campaign for a slate of progressive referenda questions. The chapter built a loose coalition of housing, homelessness, legal, and workers-rights groups around five questions: on rent control, fair wages, facial recognition surveillance, a local Green New Deal, and short-term rentals. Like in St. Paul, the campaign ran concurrently with racial justice organizing. Broadly, it was a response to a compounding displacement crisis in the city, according to Ana Laguna and Jack O’Brien who were active in the campaign. Despite landlords’ 2017 success in killing the earlier rent control effort, the cross-issue coalition was able to push through four of the five planks of their slate. Jack O’Brien said that the local landlord lobby received support from national realty groups and conservative D.C. think tanks. The local landlords “clearly called someone in Washington and got a script… it worked initially, but over five years it become less and less effective.”

Today, there are three types of rent control campaigns that are ongoing in, as of this writing, fifteen states: state fights, local fights, and fights to defend existing laws. On the state level, there are a few campaigns to institute statewide rent control systems in the handful of states that do not preempt rent control, like Rhode Island. More common are campaigns to repeal rent control bans in states across the political spectrum. Some, like those in Georgia, New Mexico, and North Carolina have stalled in 2023; others, like the one in Illinois, is in the works for 2024.

In all cases, organizers have worked hard to adapt their strategies to local conditions. In Michigan, there is what Ruth Gourevitch called “a new Dem trifecta… proud Dem unification for the first time in many years,” which has created the momentum for bold action. There, The Rent is too Damn High Coalition is mobilizing for three key goals: to repeal a rent control ban, to direct $5 billion in funds to social housing and Housing First initiatives, and to pass a comprehensive tenant bill of rights. In Colorado and Illinois, organizers seeking to repeal bans have focused their messaging on local control. These fights have not been easy, with organizers sent back to the drawing board multiple times, learning from missteps and the examples of other campaigns. Carmen Medrano, Executive Director of Colorado’s United for a New Economy, a coalition member of Colorado’s campaign to establish local control over rents, looked to the successful minimum wage fight in the state, as well as the fight over abortion access in Ohio. Despite the challenges, a repeal of a rent control ban somewhere in the U.S. seems likely in the next few years. Diego Morales, an organizer with the Lift the Ban Coalition in Illinois, said,

No one has been able to lift one of these ALEC bans… how we win this thing can be precedent-setting for other states.

In addition to these state-level fights, there are dozens of local ones. They look different depending on whether the state has an opt-in framework, like New York does. Other factors include the absence of pre-emption laws, like in Maryland. Local organizers work to identify the mechanisms and organizing strategies that make the most sense within their state’s legal and political context. In Connecticut, which has a rent control ban, Ruth Gourevitch described the push by the CT-DSA Housing Justice Project and the Connecticut Tenants Union (CTTU) to revive the state’s Fair Rent Commissions, which are a CT-specific bodies that can adjudicate tenant/landlord disputes over rent.

Local successes in one place also create space for campaigns in others. Tram Hoang told me that “once we won 3 percent [in St. Paul], the number of cities that said ‘It’s been done before’ skyrocketed.” And, indeed, in a recent successful campaign to pass a rent control law in Prince George’s County, Maryland, experts argued that a 3 percent cap was a rent control standard.

Then, there are fights to hold onto and expand existing rent control laws, whether they are brand new or a half-century old. In the latter case, the fights happen in the context of complex political horse-trading over layered rent control systems that have been amended dozens of times. After losing a fight to repeal California’s Costa-Hawkins law in 2018, the next year, tenant groups were nevertheless able to win a set of tenant protections that limit rent increases and no-cause evictions. And a referendum to repeal Costa-Hawkins is back on the ballot in 2024.

In places with more recent rent control laws, “winning is only half the battle,” as Jack O’Brien from Portland, Maine remarked. After a victory, organizers have to ensure that the system built by the city or county functions well—a major challenge, especially given that the managing government agencies are often severely cash-strapped. Any malfunctions will be seized upon by the landlords that continue to organize against rent control. In St. Paul, Tram Hoang found that landlords were keen to blame impacts on the housing market (likely pandemic-related) on the new rent control law. After that, they flexed their power over the city and its economy by going on what was effectively a capital strike in 2022. This spooked the City Council, which hastened to append a host of exemptions to the statute.

Like tenants, landlords work together to organize and adapt to shifting economic and political terrain. As New York-based organizer Charlie Dulik wrote in The Baffler last October, central to landlords’ counter-organizing is “the figure of the mom-and-pop landlord—a decades-old archetype honed into a full-fledged victim in the era of identity politics.” In New York, this fusion—the successful ideological weaponization of their anodyne image, paired with the more traditional approach of buying off state and local pols—has empowered the landlord lobby to block the passage of a statewide no-cause eviction ban for four years. It should also be noted that that a no-cause eviction ban is much less robust than the rent stabilization system that the state already has in place—and even that was vehemently opposed.

Denouncing rent control has also been incorporated into right-wing ideology, with its innumerable cultural grievances that ultimately serve the concerns of capital. This is true of Republican-controlled states as well. In the past two years, Montana, Ohio, and Florida have instituted new rent control bans, adopting well-worn red-baiting language for the contemporary moment and presenting their campaign as a principled defense of property rights. Florida’s ban is especially disheartening, because it negates the results of a successful pro-rent control referendum in Orange County (and the first in the South), won by a coalition of labor and social justice groups in 2022.

Landlord counter-organizing is troublesome enough—but in 2024, the upsurge in tenant organizing across the U.S. would ultimately encounter an existential threat: the Supreme Court. While a broad challenge to New York’s rent stabilization system was tossed out in October 2023 , two more challenges that undercut portions of the law—including the ability to regulate rents of unoccupied units (known as vacancy control), just-cause eviction protections, and the limited ability to add family members to a lease—were up for judicial review. An unfavorable ruling would have made the implementation of newly won statutes more difficult and raise serious questions about the viability of future campaigns. But on February 20th, the Supreme Court rejected the two cases from New York City’s organized landlord lobby that challenged the constitutionality of certain aspects of the state’s rent regulation system. Landlords cried to the sounds of a tiny violins and vowed to keep fighting.

In a 1960 treatise that polemicized against rent control, Friedrich von Hayek argued that its biggest impact was not economic but psychological, muddling the “Western mind” by encouraging tenant dependency on a state authority, while undermining “respect for property and the law.” As a representative of the Property Owners Association in Tennessee put it in 1947, rent control “encourages the spendthrift spirit among tenants and destroys individual initiative.”

The whole swath of anti-rent control arguments deployed by U.S. landlords essentially boil down to a common underlying logic: the logic of enforcing and protecting the racial-capitalist functions of U.S. property rights and rejecting tenants as a class—as capable and deserving participants in U.S. political and social systems. Over the past few years, tenant organizers have put up a fight against this logic, though it remains encoded in the fundamental structure of the U.S. political system. With ultra-conservative courts and a vast lobbying budget, landlords remain in a strong position. It seems clear that rent control policy in the United States, for the foreseeable future, at least, is destined to carry on with its perpetual cycle of death and resurrection.

Oksana Mironova writes about housing and cities.

The author would like to thank Ruth Gourevitch, Tram Hoang, Sumathy Kumar, Ana Laguna, Diego Morales, Dr. Alina Schnake-Mahl, Jack O’Brien, and Ritti Singh for their time and insights.