Examining India’s digital sector in relation to the world economy, we observe the following: (1) the international division of labour in the digital economy, whereby cheap labour power in India is used to raise the rate of profit of imperialist countries’ firms; (2) the domination of India’s market for digital goods and services by firms of the imperialist countries; (3) the capture and control of data, as a raw material, by these firms; (4) the use of foreign investment to capture economic territory in India; and (5) the use of political influence by U.S. imperialism to shut out rivals.

Part IV. Imperialism and the Digitalisation of India

The digital production process

Indian propagandists talk of India’s “emerging status as a technological powerhouse”, and the heads of the world’s largest technology corporations have started to refer to India as a global technology/software “superpower”, at least in their interactions with Indian media outlets.1 Undeniably, India has a large pool of technologically skilled workers (albeit small as a percentage of the country’s workforce) as well as globally competitive firms in specific sectors of software and related technology. But India’s technology sector is not a ‘superpower’, or even an emerging one. It does not disturb, let alone upturn, the existing hierarchy of world powers, even in the sphere of the digital economy. Rather, India plays an important but subordinate role in the international division of labour under imperialism.

That division of labour, as Christian Fuchs describes it,2 includes the contingent of workers who mine the minerals required for the digital sector; these minerals are then processed by various other contingents of workers, over many stages, into physical components of information and communication technology (ICT); another contingent of workers assembles these components into various finished physical goods. These stages generally span many countries, from, say, the Congo to China or Vietnam.

These physical goods are then used by workers in non-material production (among whom there is a hierarchy of tasks involved) to construct information technology. In turn, the products of their labour are used by other workers to create digital content of various types. Fuchs notes: “Today most of these digital relations of production are shaped by wage labor, slave labor, unpaid labor, precarious labor, and freelance labor, making the international division of digital labor a vast and complex network of interconnected, global processes of exploitation.” To take just one example, an army of ‘invisible’ workers around the world is employed in training artificial intelligence systems by identifying, say, a tree on a video, or correcting a translation. Amazon, Google, and other tech giants run on vast amounts of such ‘ghost work’, by workers paid less than minimum wages, without health benefits, and with no job security.3 Facebook is reported to engage at least 100,000 ‘content moderators’, and perhaps many more than that, “spread across a range of call centers, boutique firms, and ‘micro-labor’ sites around the world”,4 and similar is the case for other social media sites.

The surpluses extracted at each stage of this vast, multi-layered production process are concentrated in the hands of giant corporations which control each step. At least 6 of the world’s 10 richest persons (from the Forbes list of 2024) made their fortunes in the tech sector (Jeff Bezos, Mark Zuckerberg, Larry Ellison, Bill Gates, Steve Ballmer, Larry Page).5 Worldwide, the six largest public corporations by market capitalisation are Microsoft, Apple, Nvidia, Alphabet (Google), Amazon, and Meta (Facebook), with a combined market capitalisation of $7.3 trillion as of March 31, 2024.6

Indian IT workers in the international division of labour

Workers in India’s tech sector are located within this global division of labour. Giant multinational corporations employ them in order to reduce their own wage costs and increase their profits. Thus India’s software services exports rose from $3 billion in 1999-2000 to $100 billion in 2016-17 to almost $200 billion in 2023-24.7 Software exports are the major part of services exports, which are estimated at $340 billion for the calendar year 2023.

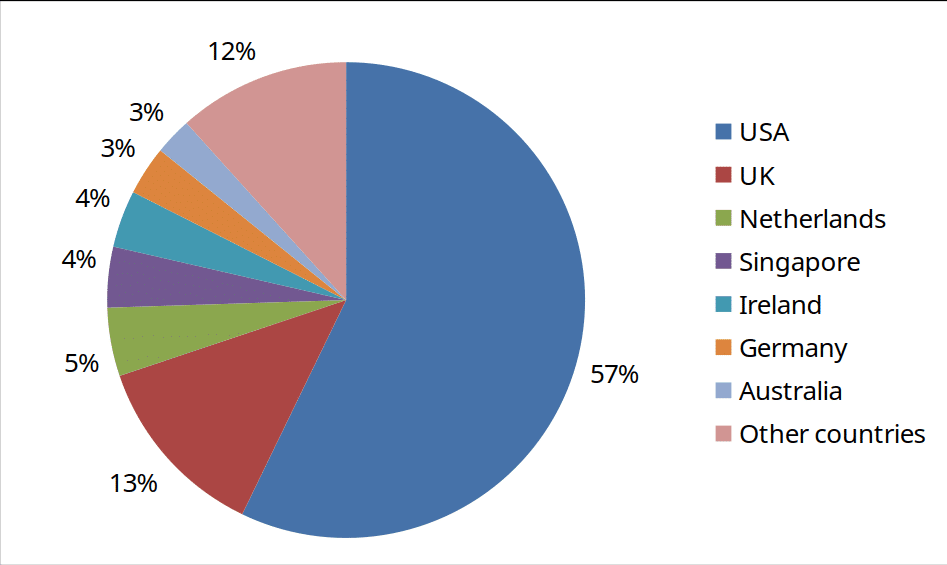

Value of Export of Software Services from India, by Country of Destination

Report on Services Export Reporting Form for 2022-23, Ministry of Commerce.

Another, and increasingly important, part of India’s services exports is that of ‘global capability centres’ (GCCs) set up in India by multinational corporations. India’s nearly 1,600 such units account for half the world’s GCCs, and employ about 1.6 million, or about 1,000 each.8 ‘GCC’ is a broad term, spanning low-skill back-office work, IT work, and research and development (R&D). Specific GCCs may do one or the other task, or combine more than one type of work.

There has been a dramatic rise in R&D work in GCCs in India, engaging over 0.5 million staff.9 According to the Financial Times, R&D capital expenditure by foreign firms in India rose more than 400 per cent in a single year, from $2.5 billion in 2021 to $12.9 billion in 2022. In that year, India supplanted the U.S., the number one for the past decade, as the top R&D foreign direct investment (FDI) destination; there are indications that this trend will continue.10 The incentive is lower labour cost: a software engineer’s salary in India is between $12,000 and $18,000 per annum, compared to the U.S. equivalent engineer’s salary of between $75,000 and $100,000.11 A Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) survey finds the number one reason for MNCs to invest in R&D in India is “availability of R&D talent pool at low cost”.12

However, the R&D carried out in the GCCs is largely unrelated to India, and does not provide impetus to Indian R&D capabilities. An observer notes that “GCCs continue to be linked directly to corporate headquarters or the headquarters of the strategic business unit. They have weak links to the MNC’s business in India.”13 A 2012 study of MNC R&D centres in India found that they had little connection with Indian institutions, and their R&D activities in India did not “reflect much importance of their Indian set-ups, or their interest in high-end R&D initiatives”. Indeed, their patents from activities in India accounted for just 0.5 per cent of their patents worldwide. The MNC R&D units maintain links with India’s university system, but not for the purpose of scientific or technological research inputs; rather, they do so in order to re-shape university education to generate more human resources of the type they require.14

As in the case of software exports, the main customer is the U.S., and U.S.-origin GCCs (global capability centres) account for 70 per cent of GCCs in India. U.S. firms feel comfortable with the environment in India: “India does not have Huawei-type companies that can challenge the pole position of global corporations in important new technologies. So, it is unlikely that we will face the kind of dispute we see on emerging telecom technologies between China and the U.S.”15 Nevertheless, foreign firms are anxious to protect their data from the Indian authorities, and hence “many GCCs have moved to a policy of storing all data on servers in the U.S. (or their parent country). In at least one GCC, computers located in the GCC have no data storage, and act more like ‘dumb terminals’ connected to the remote server.”16

What enters into the consumption of the IT worker

There is a wide range of skill levels and wages within the services exports sector. The GCCs include a large contingent of low-wage workers (earning as low as Rs 12,000 per month 17), and staff turnover is high, perhaps double of international levels.18 However, the wages of the better-paid workers in India’s digital sector are by Indian standards handsome (though a fraction of U.S. levels). The reason these wages are attractive to educated Indians is that many goods and most services are available in India at low prices, when expressed in U.S. dollar terms at the market exchange rate, i.e., $1 = Rs 83. That is, Rs 83 can buy more in India than $1 can buy in the U.S. Thus what is called the ‘Purchasing Power Parity’ (PPP) value of the rupee is higher than its market exchange rate value. Behind this seemingly benign phenomenon lies the fact that vast numbers of people in India, particularly in the informal sector, work for very low wages or returns, and therefore the things they make are cheaper. (The unpaid toil of women too hugely helps keep down the reproduction costs of the working class family.19)

So the Indian tech worker’s ability to enjoy a comfortable standard of living at a relatively low U.S. dollar wage (and therefore the foreign employer’s ability to hire him/her at that low dollar wage) depends on, in effect, a subsidy provided by India’s sweated informal sector and women’s labour.20 Without the vast reserve army of labour, as manifested in India’s low employment rate 21 and its vast informal sector, the wages of IT workers too would have to be higher, and the profits of firms outsourcing to India would be lower. In that sense, the continued growth of India’s IT industry depends precisely on its remaining an enclave, drawing on a large periphery. It is important to realise that the demand-suppressing policies by the Indian State, in the name of controlling the fiscal deficit and checking inflation, serve to maintain the reserve army of labour and keep down wage levels. In this fashion, the distorted pattern of development in India reproduces itself under imperialist domination.

Imperialist domination in the digital sphere

The dominant media have long associated certain ideological conceptions with the internet, such as freedom of individual expression and freedom of choice. One such conception is that the internet has put individuals worldwide on an equal footing; in the words of an American propagandist, “the world is flat”—an epiphany he claims to have had in India.22 The reality is that the digital world is marked by imperialist domination; and India is a prime example of this.

While several writers have talked of ‘imperialism’ or ‘colonialism/colonisation’ in the digital sphere, the meanings they have attached to these terms are very diverse, and, in some cases, divorced from a broader political-economic analysis of the world economy and politics. We take, as our frame, the relationship between the monopoly capital of the world’s wealthiest and most powerful countries and the mass of humanity in underdeveloped Asia, Africa and Latin America, a relationship which shapes the world’s material and financial flows, its physical environment, its cultural life and its political developments.

Over 100 years ago, Lenin, in his Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism (1917), described the process of concentration of capital in the later 19th century, which rendered the ‘free market’ a thing of the past. Giant monopolist associations emerged, backed by, or merged with, big finance. For their survival and growth, these monopolists were driven to seize the sources (and even potential sources) of raw materials and conquer foreign markets as well. All this was done with the help of State power. Foreign investment was an important instrument of extending monopoly hold. In this process, monopolists secured profitable deals, concessions, monopoly profits, and so on—“economic territory in general”.

“In [the] backward countries”, said Lenin, “profits are usually high, for capital is scarce, the price of land is relatively low, wages are low, raw materials are cheap.” Even more important than the benefit the monopolists obtained by getting control of raw materials and markets was the benefit they obtained by denying their rivals access to the same. So they constantly strove to gain political influence, colonising countries, creating “spheres of influence”, and so on. Lenin remarked: “There are already over 100 such international cartels, which command the entire world market and divide it ‘amicably’ among themselves—until war re divides it.” Employing a historical-materialist method of analysis, he brought out the intertwining of economic and geopolitical aspects in the entire process.

The forms of imperialism may have undergone some change in the century since Lenin’s work, but there are striking continuities in its content. When we apply this perspective to India’s digital economy, we observe:

1. the creation of an international division of labour in the digital economy, whereby cheap labour power in India is used to raise the rate of profit of imperialist countries’ firms;

2. the domination of India’s market for digital goods and services by firms of the imperialist countries;

3. the capture and control of data, as a raw material, by these firms;

4. the use of foreign investment to capture economic territory in India;

5. the use of political influence to shut out rivals, if necessary even by war.

We have already discussed point 1 above. Let us look at points 2-5 below.

Hardware dependence

The hardware industry of computers, electronics, and optical products contributes to only 0.1 per cent of India’s gross value added (GVA).23 As Dhar and Joseph note, “While the ITES [Information Technology Enabled Services] segment of the Information Technology (IT) sector has performed exceptionally well, the other component of the industry, the Indian computer electronics industry, has not been able to establish itself as a distinct entity, despite its emergence in the 1960s.”24 This despite the glimpses of India’s technological potential in the performance of two institutions set up in the 1980s: the Centre for Development of Telematics (C-DoT), which was responsible for the initial spread of telephony in India till the 1990s, and the Centre for Development of Advanced Computing (C-DAC). Sudip Chaudhuri observes,

In the pre-reforms period, domestic manufacturing of telecom equipment was essentially sustained through public procurement and import substitution policies…. Mandatory purchase requirement did not make C-DoT less efficient. In fact C-DoT showed that it is possible not only to develop technologies as per international standards. The products can be cheaper and more suited to Indian conditions.25

Meanwhile, in the face of the denial of supercomputer technology by the U.S. and Japan, the C-DAC produced the Param supercomputer in 1991; “From its very first generation,”, Dhar and Joseph observe, the “Param supercomputer was ranked among the best machines in the world”.26 While these instances were not part of a comprehensive programme of building independent manufacturing capacity, they did provide glimpses of what is possible if one wants to promote indigenous capabilities.

The period of liberalisation and globalisation, however, saw India turn to near-complete dependence on imports of telecom gear and computer electronics.27 The ‘Make in India’ programme announced by the Prime Minister in 2014 claimed it would make India into a global manufacturing hub, including the domestic manufacture of mobile phones. Superficially, there was a sizeable increase in such ‘manufacture’; but in fact, import dependence only deepened, as a 2020 study by Sunil Mani brought out:

Domestic production has been dependent on parts that were imported from abroad, and these imports have been growing [imports of parts of mobile phones rose from $2.67 billion in 2014 to $11.56 billion in 2018]. Given the fact that production is largely based on imported inputs, the ratio of gross value added (GVA) to gross value of output (GVO) has been declining sharply, especially during the period when domestic output has been increasing [GVA/GVO declined from 17 per cent in 2013-14 to 13 per cent in 2017-18]…. As such, no domestic production or innovation capability has been created or is in the offing in the foreseeable future. This dependent development has led to India’s technology trade deficit increasing on account of increased royalty and licence fee payments, besides dividends and profits being repatriated abroad.28

Indeed, an RBI study of India’s digital economy noted indications of increasing in import dependence between 2014 and 2019 in computers, electronics, and optical products.29

In 2020-21, during the Covid lockdown, the Indian government announced a ‘Production-Linked Incentive’ (PLI) scheme, the stated aim of which was, once more, to promote manufacturing in India. There appeared to be a dramatic improvement in India’s net exports (i.e., exports minus imports) of mobile phones, from -$3.3 billion in 2017-18 to a $9.8 billion in 2022-23—a turnaround of $13.1 billion. The turnaround started in 2018-19, when import tariffs on mobile phones were raised, and accelerated in 2020-21, after the PLI scheme was announced.

However, an analysis by Raghuram Rajan, Rohit Lamba and Rahul Chauhan of mobile phone manufacturing in India reveals that, in the same period, the import of inputs for mobile phones (semiconductors, printed circuit board assemblies [PCBAs], displays, cameras and batteries) rose steeply. The combined net exports of mobile phones + inputs in fact sharply worsened, from -$12.7 billion in 2016-17 to -$21.3 billion in 2022-23; thus “it is entirely possible that we have become more dependent on imports during the PLI scheme!” Even after providing for various other possibilities, the net figure of exports remains negative. Moreover, Rajan et al. point out that the PLI subsidies are expressed in terms of the final value of the phone, not on the value added in India. The manufacturing cost of an Apple iPhone 12Max is only one-third the value of the phone, value added at the stage of assembly is only 4 per cent of the manufacturing costs; that is, assembly would amount to only 1.33 per cent of the final value of the phone. Whereas PLI subsidies are initially 6 per cent of the value of the phone, falling by the end of five years to 4 per cent, of the value of the phone. Since only assembly appears to be taking place in India, the subsidies may well be larger than the value added.30 Moreover, state governments add to the PLI subsidies by providing tax incentives, power and subsidised land.

As we shall see later in this article, the western imperialist countries used their political influence to shut out rivals from the Indian telecom market, bearing out Lenin’s political-economic analysis.

Capture of the digital market

In October 2015, the Indian Prime Minister visited Silicon Valley in the U.S., home to Big Tech, where he received a rousing reception. As former Infosys chief financial officer, T.V. Mohandas Pai, rapturously explained:

Why was there this great interest in Mr. Modi in the Valley? Well, Americans, Indians, and techies saw in him a tech-savvy leader who was pro-business, decisive, articulate, charismatic and who exuded strength. They recognised that India was the last great, unconquered digital market after China and Prime Minister Modi’s Digital India project could empower 1.25 billion people in India digitally…. They all wanted a piece of the action. So, Microsoft, Facebook, Google and Apple, who want to own the whole world digitally, saw in Mr. Modi the answer to their dreams.31

India’s digital market is overwhelmingly captured, or, to adopt the term Michael Kwet uses in the context of South Africa,32 “colonised” by a handful of U.S. multinationals. Table 1 presents the shares of different U.S. firms in India’s digital market:

Table 1: Market Shares of U.S. Digital Firms in India, 2024

| Category | Market shares | Combined market share | ||

| Social media | Facebook (Meta) 70% | Instagram (Meta) 21% | Youtube (Alphabet) 6% | 97% |

| Search engine | Google (Alphabet) 98% | Bing (Microsoft) 1% | 99% | |

| Browser | Chrome (Alphabet) 88% | Safari (Apple) 2% | Edge (Microsoft) 1%, Firefox 1% | 92% |

| Mobile operating system | Android (Alphabet) 95% | iOS (Apple) 4% | 99% | |

| Desktop/laptop operating system | Windows (Microsoft) 72% | 72% | ||

| Ecommerce | Flipkart (Walmart) 47% | Amazon 42% | 89% | |

| Messaging apps | Whatsapp (Meta) | Facebook Messenger (Meta) | Snapchat, Telegram, Signal | |

| Payment apps | Phone Pe (Walmart) 48% | Google Pay (Alphabet) 37% | 85% | |

| Cloud services | Amazon Web Services 33% | Microsoft Azure 21% | Google Cloud Platform 11% | 66% |

We could not trace percentage shares for messaging apps, but we have given the names of the dominant firms. Among social media, the names of X (formerly Twitter), Pinterest and LinkedIn have been left out for lack of space.

Sources: ‘statcounter’ and media reports.33

As can be seen from Table 1, the percentages reflect complete domination by U.S. firms. In several cases, a single U.S. firm constitutes virtually the whole market, such as Meta in social media (91 per cent), Alphabet in search engines (98 per cent), Alphabet in browsers (88 per cent), Alphabet in mobile operating systems (95 per cent), and Meta in messaging apps (likely > 90 per cent). In e-commerce and payment apps, just two U.S. firms enjoy a combined market share of over 85 per cent. In desktop/laptop browsers, the growing popularity of the open-source Linux in India 34 is a positive development, but Microsoft still commands 72 per cent of the market, including most Government computers. (The Government of India has set up the National Resource Centre for Free & Open Source Software, which has produced, and is distributing, an indigenized GNU/Linux Operating system distribution “Bharat Operating System Solutions”, or BOSS. However, the Government itself runs its computers on Microsoft Windows. Only in August 2023, after a series of malware attacks, did the Defence Ministry shift to a Linux-based operating system; the three armed forces services, however, have yet to shift, and there is no near-term prospect of the rest of the ministries joining.35)

The revenues earned directly by the tech giants from India are sizeable, and promise to grow further. Digital advertising has grown dramatically in India, from 11 per cent of total advertising revenue in 2014 to 45 per cent in 2023. It is now the single largest category of advertising, surpassing television (33 per cent) and print (16 per cent).36 Of a reported total digital advertising of Rs 55,000 crore in 2023, Google India garnered Rs 28,040 crore and Facebook India Rs 18,308 crore;37 Amazon and Walmart-owned Flipkart appear to have earned most of the rest. (Internationally, Google and Facebook have established a duopoly of the digital advertising market. A 2018 deal between the two to share the U.S. advertising market has been challenged in U.S. courts.38)

Another Indian subsidiary of a U.S. tech giant, Microsoft India, saw its revenues rise 39 per cent in 2022-23, to Rs 19,229 crore. Its single largest cost was royalty to its parent company: Rs 13,139 crore in 2022-23, an increase of 52 per cent from 2021-22.

Monopolistic practices

The Parliamentary Standing Committee on Finance (chaired by Jayant Sinha), in its 53rd Report (December 2022), presented a summary of the “anti-competitive practices by Big Tech companies” in India. It argued that underlying economic drivers of digital markets lead to the rise of a relatively few leading players, referred to as Big Tech companies. In addition to the traditional advantages of size, there are powerful ‘learning’ and network effects (for example, the more people who use a search engine, the more useful it becomes to users). As a result digital markets often tip quickly (within three to five years) to winner-take-all monopolistic markets. Once monopoly has become a fact, it is difficult to do anything about it; regulation needs to be ex ante (before the event). Moreover, leading players in one digital market can quickly unlock these benefits in adjacent markets as well.

In the absence of sufficient competition, digital markets are prone to anti-competitive behaviour by leading players. These include charging exorbitant commissions to businesses (Google charges 30 per cent commission for app purchases), preventing business users from moving out of the platform, manipulating users towards the platform’s own products/services, forcing consumers to buy related services, monopolistic use of non-public data to their own benefit, extending market power through the buying up of start-ups, offering huge discounts in order kill off competition, forcing businesses to enter into exclusive tie-ups with the platform, preferential ranking of search results in favour of sponsored products, restricting the installation/operation of third-party applications, and using monopoly power in their advertising policies (for example, extorting digital news publishers).39

Circumscribed debate

As we write this, the Government’s draft Digital Competition Bill, which is partly based on the findings of the Parliamentary Standing Committee, has been circulated to the public for responses. According to the media discussion, the draft Bill aims to curb the market dominance of ‘Big Tech’. Important features of the draft include the designation of Systematically Significant Digital Entities (SSDEs); these would be subject to regulation, even before the event, to prevent anti-competitive practices such as those listed in Table 2. If SSDEs nevertheless engage in such practices, they can be fined up to 10 per cent of their global turnover. Moreover, their associate companies, even if smaller, would face the same strictures as them.

Pressure for such a legislation has come from other businesses, who are at the mercy of the Big Tech firms. Nearly 40 start-ups, including some prominent ones, wrote to the Ministry of Corporate Affairs in support of the draft Bill. On the other side, Big Tech has mobilised its forces, and the media are filled with warnings about the dangers of the draft Bill, how it will stifle innovation, how it will be difficult to implement, and so on.

However, the scope of the present debate is limited to whether or not such monopolies should be regulated, and the best method of regulation. Absent from the debate is any questioning of whether such monopolies should be allowed to remain. If monopolies are inevitable (due to ‘learning’, network effects, and high entry costs), should they remain under foreign, or even private Indian, ownership, or be replaced by public utilities? It has been accepted since the 19th century that certain industries may be ‘natural monopolies’: for example, it is socially inefficient for two rival railway firms to lay competing rail lines along the same route. In the 20th century, it came to be accepted that natural monopolies should be in the public sector, so as to prevent private capital extracting monopoly profits.

In this fashion, the public sector included not only the railways but postal services, electricity, telephones, and water supply. The Thatcher-Reagan wave of privatisation of public utilitiesof the 1980s resulted in widespread harm, such as the dramatic deterioration of the British railways, merely underlining the importance of public ownership. In the present day, the infrastructure of computer/mobile operation, browsing, search, messaging, payment, storage, and social exchange are essential utilities which cannot be placed in the hands of private corporations.

The effect is even more pernicious when the corporations are in the hands of imperialist countries, and the users are citizens of countries which have long remained under colonial and neocolonial domination. Indians may recall two features of the Railways under British rule: they were designed to serve not Indian but British interests, such as raw material extraction from the interior to the ports; and, in the hands of British private monopolists, they served as one of the principal elements of the drain of wealth from India.

In theory, India should be particularly well-placed to shut out Big Tech, since (1) it has ample technological talent, much of which at present is engaged in dead-end work for Big Tech; (2) it generates vast amounts of raw material (data of users) necessary for, say, an effective search engine or social media site; and (3) it has a large market. It would, no doubt, require a different political economy and State power for India to do so, and to do so in a fashion that expands democratic participation rather than represses it; but it is important to assert this as a necessary task. Such a venture could also be part of a broader project of countries which have faced colonial and neocolonial domination.

It is striking that the foreign ownership of basic digital utilities is not a subject of public discussion, let alone debate. Not a single prominent political party, to our knowledge, has mentioned the question of foreign ownership, and its implications.

The brief life of ‘data colonisation’

However, the foreign ownership of Indian data has been the subject of public discussion. (The following passage repeats some material from our book Crisis and Predation: India, COVID-19, and Global Finance, 2020.) In January 2019, Mukesh Ambani, the owner of Reliance and therefore of telecom firm Reliance Jio, called on the prime minister to end “data colonisation” by global corporations:

Today, we have to collectively launch a new movement against data colonisation.

In this new world, data is the new oil.

And data is the new wealth.

India’s data must be controlled and owned by Indian people—and not by corporates, especially global corporations.

For India to succeed in this data-driven revolution, we will have to migrate the control and ownership of Indian data back to India—in other words, Indian wealth back to every Indian.

Recall that, between starting operations in 2016 and 2019, Ambani’s telecom firm, Reliance Jio, with cut-throat measures and some help from the telecom regulator, grabbed 400 million customers from other firms. In the process it drove nine firms out of business and left another two on the ropes, leaving only one serious rival. This was possible because Reliance had access to finance to bankroll losses (even as it provided free voice and cheap data for an extended period). In the process of trying to compete with Reliance, the whole sector was driven into a collective $75 billion debt.

After capturing the market, Jio proceeded to sell shares to foreign investors. Between April and July 2020 U.S. tech giants Facebook, Google, Qualcomm and Intel, as well as six U.S. private equity firms and three sovereign wealth funds of Abu Dhabi and Saudi Arabia, invested a total of $20 billion in Reliance Jio, wiping out Jio’s debt. Foreign investors now held almost one-third of Jio, and Facebook and Google won representation on the board—a first for any Reliance firm. Microsoft, a major supplier of cloud services in India, had already formed a “long term alliance” with Jio in August 2019 to set up data centres.40

With the local monopoly house now as partner, concerns regarding data colonisation appear to diminish. In 2019, when Ambani issued his clarion call for decolonisation, Facebook’s 15 data centres were distributed across North America (10), Europe (4), and Asia (1 in Singapore).41 They remain so today.42 Google has 18 data centres in North America, 10 in Europe, 3 in South America, and 3 in Asia (Japan, Taiwan and Singapore).43

The business models of Alphabet (parent of Google) and Facebook depend precisely on mining the data of users, or “data colonisation”, as Ambani called it earlier. The president of Microsoft India rejoices in the prospects of his firm in India:

We will soon be the most populous nation on the planet, and if a billion of those people have devices with them that are generating data every moment, you have a natural advantage of creating data…. And if all of them are on digital platforms, combined with our regulation and tech environment to do work here, it is a natural outcome that we can become the data capital of the planet.44

As pointed out by John Bellamy Foster and Robert McChesney, “the major means of wealth generation on the Internet and through proprietary platforms such as apps is the surveillance of the population.”45

Furthermore, major U.S. Internet firms such as Google, Facebook, Microsoft, and Yahoo provide the U.S. government agencies direct access to their users’ data, thus forming what has been called a “government-corporate surveillance complex.” In turn, “the U.S. government is little short of a private army for the Internet giants as they pursue their global ambitions.”46

Digital doorway for FDI in retail trade

The strange restriction and distortion of the public debate regarding foreign investment in India can also be seen with regard to India’s retail trade. Till around 2012, there was widespread opposition to the entry of foreign direct investment in retail trade. ‘Trade’ accounted for the employment of about 44 million workers in 2011-12. Since organised retail would be relatively less labour-intensive than traditional retail trade, even a small shift of the market away from traditional retail to organised retail would result in the loss of livelihoods on a large scale. When the Congress-led government liberalised foreign direct investment (FDI) in retail trade in 2012, the Bharatiya Janata Party declared:

The decision of the Congress led UPA government to allow FDI in multi-brand retail has drawn all round criticism and condemnation. In the name of ‘reform’, the government has in fact compromised the long-term national interest…. the Congress led UPA has buckled under foreign pressure. The decision is sure to have its impact on millions of small traders who are going to lose their jobs.47

The BJP’s 2014 election manifesto opposed FDI in multi-brand retail. However, once in power, the BJP government allowed 100 per cent FDI in multi-brand retail under the automatic route. It drew a distinction between a “marketplace model”, which merely connects sellers to buyers, and an “inventory-based model”, which stocks inventories of goods and supplies them to buyers. The inventory-based model was prohibited, but the marketplace model was allowed. At the same time, the policy stated: “E-commerce marketplace may provide support services to sellers in respect of warehousing, logistics, order fulfillment, call centre, payment collection and other services.”48 In practice, the distinction between the marketplace model and the inventory model disappeared.

Moreover, the Government stipulated that the marketplace model would be allowed on condition that it would be “business-to-business (B2B)” and not “business-to-consumer (B2C)”. That is, firms would sell to other firms, but not to consumers, through digital platforms such as Amazon. There is a surreal humour in the Government’s repetition of such mantras, even as, in fact, Amazon, Flipkart, Myntra, and other FDI digital firms sell directly and openly to consumers on a massive scale. In response to Parliamentary questions, the Government acknowledges that it has received multiple complaints from traders and industry associations against FDI e-commerce firms for violation of the policy, but there is no action taken against them.49

The entire question of the invasion of India’s retail sector by global giants, and the consequent destruction of employment in India, has disappeared from, or been removed from, political discussion. In Government forums, the sole representative of India’s vast retail trade is an organisation called the Confederation of All India Traders (CAIT), headed by Praveen Khandelwal; he has recently been selected as the BJP candidate for the Chandni Chowk constituency in Delhi.

The Covid-19 pandemic accelerated the growth of e-commerce retail;50 since overall consumption was hit by the lockdown, and after the post-lockdown recovery, has continued to limp, the growth of the e-commerce sector would have been at the cost of traditional retail. Future growth of traditional retail will be eaten into: A Deloitte report projects that traditional retail’s share of India’s retail market will fall by 9.4 percentage points between 2022 and 2030, which would be transferred to online retail.51

Even as the share of traditional retail has been taken away by FDI firms, over 12 million more persons have entered the retail trade sector (between 2012 and 2022). This is a sign of economic distress; they have entered retail for lack of other employment. This translates into lower income per worker.

The loss of livelihoods in traditional retail is not on account of the superior efficiency of e-commerce. All major e-commerce firms have made losses for years on end. For example, in the financial 2022-23, Flipkart India made a loss of Rs 4,891 crore, while Amazon India made a loss of Rs 4,854 crore. Not only have they incurred losses since their inception, but the losses have increased (rising in 2022-23 by 45 per cent for Flipkart, and 33 per cent for Amazon). Why do they continue to operate, if they make losses? Evidently because they are carving out a market share, displacing other sellers; and they have the financial strength to sustain this. Once they have displaced the competition, they can set about making profits. It is thus not superior efficiency as such, but financial clout, that explains the growth of the FDI firms. The same, as we shall see, holds for the entire ‘start-up’ sector in India.

The takeover of start-ups

The rapid growth of ‘start-ups’ in India is projected as a matter of much pride for India: “start-ups will continue to be the messengers of India’s entrepreneurial dynamism”, says the Economic Survey 2022-23. However, as we shall see, the most valuable start-ups are in the financial grip of international capital.

The Indian government defines a start-up (for the purpose of receiving assistance under special Government schemes) as an entity not older than 10 years; a private limited entity, or a partnership firm, not a public limited company raising equity funds from the market; with an annual turnover not over Rs 100 crore; and “working towards innovation, development, or improvement of products or processes or services or a scalable business model with a high potential for employment generation or wealth creation.” From the launch of the Startup India initiative in 2016 to April 2023, the Ministry of Commerce has recognised more than 98,000 entities as start-ups.52

What makes ‘start-ups’ the object of so much acclaim? Actual employment generation does not appear to be important: if we accept Government figures for number of start-ups (117,000) and total employment generated (1.24 million) since 2016, average jobs are only 10.6 per start-up.53(These figures are based on self-reporting, and they may not take into account retrenchments and closures.) The critical features, then, are “innovation, development, or improvement of products or processes or a scalable business model with a high potential for… wealth creation.” Most definitions require start-ups to be in some way technology-enabled, or ‘tech start-ups’; and the real interest in these firms revolves around their prospects for ‘wealth creation’, or enriching financial investors.

In the financial world, different definitions of ‘start-ups’ are in use, with some using a cut-off of 10 years, others going back to the year 2000. India has generally been recognised as having the third largest start-up sector in the world, after the U.S. and China. ‘Unicorns’ are defined as start-ups which have achieved a market valuation of at least $1 billion. The National Investment and Promotion Facilitation Agency put the number of unicorns as of September 2022 at 107, with an aggregate valuation of $341 billion.54 NASSCOM says that at end-2023 India has more than 31,000 tech start-ups, with 91 active unicorns;55 CB Insights puts the figure of Indian unicorns at 71 in March 2024.56 (The differing figures are likely on account of different cut-off dates and definitions.) Whatever the definition one chooses, it is clear that, at least in financial terms, large valuations have come into existence through India’s start-up sector.

Finance in the driving seat

An important feature of the sector is that, in order to acquire a share of the market, start-ups must run for several years and market their services, during which period they make, not profits, but substantial losses. An RBI study points out that “tech-startups may need to scale up rapidly to capture the market, requiring frequent and substantial capital infusions. Additionally, reaching the socially optimal level of provision may require temporary promotional schemes (inter alia, offering services at a low or zero introductory price).”57

Thus, to sustain a start-up during this period requires substantial financial infusions, which go through several rounds. Initially, the founders may put in money from their own pockets, family or friends; but very soon, they must raise money from funders in successive pitches or rounds (Seed, Series A, B, C and so on). Eventually, if the start-up survives and does well, its founders hope for one of two outcomes: that it is able to raise capital from the market through selling shares (an Initial Public Offering, or IPO), or that it gets acquired by an existing, larger, firm.58

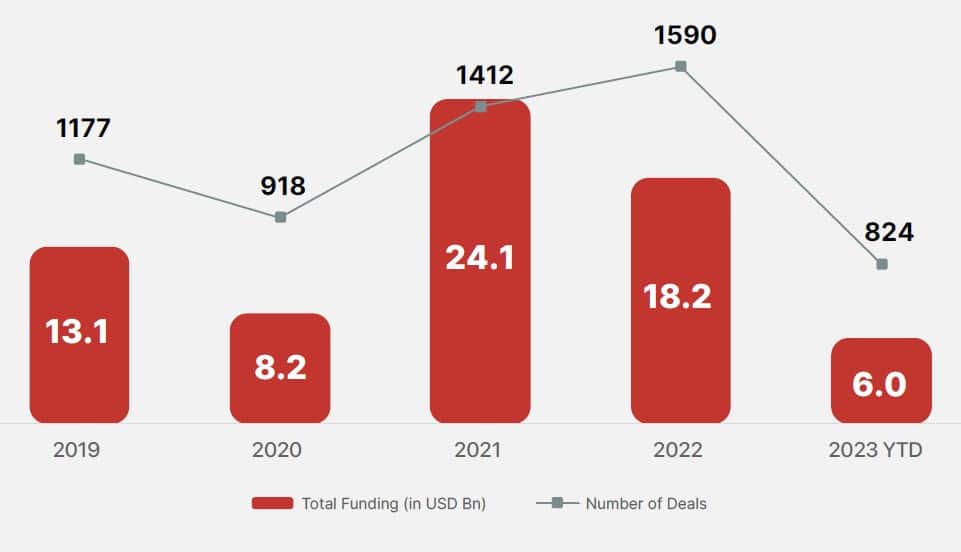

The Government likes attribute the surge in the number of Indian start-ups during 2021 to the entrepreneurial capabilities of Indians, and of course to the Government’s own policies. However, there has been a slowing-down in 2022 and 2023; many consider the growth of the sector to have “stalled”. The reality is that the surges and slumps are linked to U.S. monetary policy: when funds are available cheaply internationally as a result of the US’s reduction in interest rates and expansion of money supply to stimulate its own economy, a portion of those funds finds its way to Indian start-ups. When U.S. monetary policy tightens, the start-up sector in India (and elsewhere) dries up. The RBI acknowledges that “We find that fundraising may be influenced by global financial spillovers.”59

Funding in Indian tech start-ups, by calendar year

NASSCOM-Zinnov, 2023.

The rewards for early investors in a successful start-up can be very large, but so too are the risks. For start-ups founded in India between 2012 and 2021, the likelihood of a start-up turning into a unicorn stood between 0.008 per cent and 0.12 per cent, depending on the year in which it was founded. The likelihood of getting acquired (across years) stood at 1.3 per cent. The possibility of raising money through the IPO route is extremely tiny—only 86 start-ups went public between 2014 and 2022. Whereas, of the 14,000 start-ups founded in 2015, 38 per cent were ‘deadpooled’—i.e., shut down—by 2022.60 In these circumstances, it is overwhelmingly foreign investors who are able and willing to gamble on finding the ‘winners’. The RBI study notes that “founders often cede equity and a degree of managerial control to investors.”

The capture of economic territory

As a result, the major start-up firms, which we are told represent the future of Indian business, are largely owned by international investors, principally U.S. investors. The CB Insights list of 71 Indian unicorns provides details of the principal investors in each, totalling in all 91 investment firms. Barring a handful of investments by Indian corporate houses, the rest are foreign financial investors, very largely U.S. firms. Many of these figure among the principal investors in several unicorns. The following Table presents details of those which are major investors in more than three unicorns. Of the 9 listed, 8 are U.S. investors, of which 7 are headquartered in Mensa Park, Palo Alto, California.

Table 2: Major Investors in >3 Indian Unicorns

| Investor | No. of Indian unicorns in which invested | Based in |

| Sequoia Capital India | 23 | US |

| SoftBank Group | 12 | Japan |

| Accel India | 11 | US |

| Tiger Global | 11 | US |

| Lightspeed India Partners | 7 | US |

| Matrix Partners | 6 | US |

| Norwest Venture Partners | 5 | US |

| Nexus | 4 | US |

| Elevation Capital | 4 | US |

Source: Tabulated from https://www.cbinsights.com/research-unicorn-companies

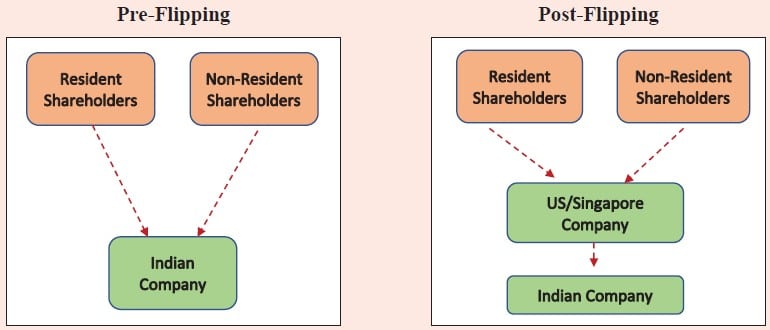

Either in response to foreign investors’ demands, or on their own, large numbers of Indian start-ups have ‘flipped’ over the years. ‘Flipping’ is “the process of transferring the entire ownership of an Indian company to an overseas entity, accompanied by a transfer of all intellectual property (IP) and all data hitherto owned by the Indian company. It effectively transforms an Indian company into a 100 per cent subsidiary of a foreign entity, with the founders and investors retaining the same ownership via the foreign entity, having swapped all shares.”61

Effect of flipping on the structure of the company

Economic Survey 2022-23.

To clarify: this goes further than mere ownership of the shares of an Indian start-up by foreign investors. Flipping involves re-incorporating the start-up abroad, thereby placing it beyond the reach of the Indian State. This is a massive, silent transfer of wealth out of India. Astoundingly, there appear to be no aggregate official data about the scale of this phenomenon, leaving various private research firms to make their own guesstimates. The fact that start-ups, by definition, are not listed on the stock market makes gathering data about them more difficult, but flipping appears to be widespread. One report of 2022, restricted to ‘unicorns’ (firms with valuations of $1 billion or more) found that, of the 90 Indian unicorns at that time, 34 had flipped: 25 to the U.S., 8 to Singapore, and 1 to the Netherlands.62 Another report of the same year claimed that, of a total 130 ‘unicorns’, 40 were now headquartered in the U.S.63 Many of the most well-known start-ups have left Indian jurisdiction in this fashion: one consultant claimed that two out of three well-known start-ups had flipped by 2021.64

The Indian government has silently watched this parade of start-ups departing with their Indian-made intellectual property, data and customers. Its response has been restricted to persuading such firms not to leave, or persuading departed firms to return. Some successful start-ups do return, in a process called ‘reverse flipping’, when it is advantageous to them, such as when they wish to raise money from the Indian share market. At that juncture the Indian State is able to extract some taxes from them. The Economic Survey 2022-23 devotes a section to this question, without revealing any aggregate data on the question.

U.S.-India strategic ties

We close with what Lenin referred to as the “phase of particularly intense struggle for the division and the redivision of the world” carried on by great powers. The Indian digital sector is a prize of some value in this struggle.

As we have seen, the Indian digital sector is closely tied to the U.S. The principal customers of Indian IT exports are U.S. firms. The principal platforms, apps, and software in use in India are of U.S. firms such as Facebook, Google, Amazon, Apple and Microsoft. The principal foreign investors in India’s start-up sector are U.S. investors. To a large extent, this is due to the U.S. global dominance in the technology and finance sectors, but it also reflects the strategic ties between the rulers of the U.S. and India. This strategic factor has been greatly strengthened in the last decade.

In an earlier writing (in 2020),65 we laid out the following interlinked developments:

- The U.S. and its allies have concluded that China is a strategic rival, and consequently they have mounted a military and economic campaign to prevent its further growth. As part of this, they are waging a technology war, blocking the entry of its products (e.g. Huawei) into different markets, trying to prevent the advance of its technology (e.g. in sophisticated chips), and encouraging firms to shift their supply chains out of China and into ‘friendly’ countries like India. The U.S. has won India as an ally in its ‘containment’ of China.

- The Indian rulers, on the other hand, nurse ambitions of being recognised as a global power. In this they see China as a regional rival and the U.S. as a superpower that can assist them in getting them recognition as a global power. The Indian rulers therefore have forged extensive military ties with the U.S., and have endorsed the US’s concept of the ‘Indo-Pacific’ as a region in which China should not be allowed to spread its influence.

- In this course, relations between China and India have deteriorated, and a series of border clashes erupted during the Covid-19 pandemic. In the wake of these clashes, India not only formed even closer military ties with the U.S., but banned 59 Chinese apps such as TikTok; effectively banned the Chinese telecom firms Huawei and ZTE (which had a major part in India’s 4G) from competing for 5G contracts in India; placed checks on Chinese investment in India; imposed tariff and non-tariff measures to reduce the import of Chinese goods; promoted Indian firms to replace Chinese goods such as solar cells and computer chips; and made strenuous efforts to woo multinational corporations to replace China with India in their supply chains. The Government’s ‘Atmanirbhar’ (‘self-reliant’) programme provides sizeable subsidies to not only Indian firms, but also foreign manufacturing firms, such as Apple and Samsung, to manufacture in India. (We have touched on this in the present article in the context of Apple receiving subsidies even larger than their value added in India.) As events unfolded since 2020, India has not had much success in decreasing its dependence on Chinese industrial imports; quite the contrary.66 Nevertheless, the intent behind these measures is clear.

- One result of this ‘cold war’, in which India has been roped in as a junior partner, is that India is more closely tied in with western, and specifically U.S., interests even in purely commercial matters. This has raised its costs: for example, one study found that banning Huawei from India’s 5G equipment market would raise costs by 8-29 per cent. In earlier generations of equipment, Huawei prices were reported to be up to 40 per cent lower.67

The implications, however, are not only economic. As indicated in our earlier writing, investments by Facebook and Google in Jio (as well as Jio Cinema’s more recent merger with Disney Hotstar) and the dominance of U.S. firms in India’s social media signify a long-term alliance with political implications.

In closing, we wish to clarify a few points, to avoid possible misunderstanding of our argument.

(1) We do not suggest that the Indian people are necessarily helpless in their dependence in the digital sphere; on the contrary, we argue that there is considerable capability and economic potential among different sections of the Indian people. What is missing is the political-economic structue in which these could have been properly developed.

(2) We also do not suggest that Indian big business is supine in its dependence. It has certain competencies—for example, it has managed its IT firms professionally, seized international opportunities and adapted to the changing needs of the market. Indian big business also enjoys substantial financial clout, and it has used its links with the local milieu and bureaucracy to occupy strategic positions in the economy. On that basis it has periodically extracted a share in the pickings of international capital in India.

However, Indian big business, from its birth under colonial rule and through its subsequent long development, has tended to favour a mercantile outlook rather than a thoroughgoing capitalist one, looking for short-to-medium term profits. The outcome can be seen, among other things, in India’s digital sector.

(3) We do not suggest that the Indian State is simply prostrate before U.S. imperialism. From time to time, frictions erupt between the two, and there is periodic haggling between them in both the economic and strategic spheres. Moreover, the relationship is not set in stone; if there were to be a change in the strengths of imperialist powers worldwide, the Indian State might shift its position in line with that—without breaking out of the overall framework of dependence. To break out of the all-round dependence evident in India’s digital sector (as in several other sectors) would require basic changes in India’s political economy; those are beyond the scope of the present article.

Footnotes:

- ↩ Nandan Nilekani and Tanuj Bhojwani, “Unlocking India’s potential with AI”, Finance and Development, IMF, December 2023; Justinas Vainilavičius, “Nvidia courts ‘global technology superpower’ India”, cybernews, November 15, 2023, https://cybernews.com/news/nvidia-courts-technology-superpower-india/; Surabhi Agarwal, “Software superpower India to join world data capitals: Microsoft Corp president Brad Smith”, ETtech, September 6, 2022.

- ↩ Christian Fuchs, “Digital Labor and Imperialism”, Monthly Review, January 2016.

- ↩ Mary Gray and Siddharth Suri, Ghost Work: How to Stop Silicon Valley from Building a New Global Underclass, 2019.

- ↩ Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power(2019), pp. 475-76.

- ↩ Forbes World’s Billionaires List, The Richest in 2024.

- ↩ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_public_corporations_by_market_capitalization, accessed May 17, 2024.

- ↩ NASSCOM, Rewiring Growth in the Changing Tech Landscape, Technology Sector in India, Strategic Review 2024.

- ↩ Vidya S., “India’s global capability centres thrive amid IT slowdown: From support to innovation, hiring surges”, Business Today, February 4, 2024.

- ↩ https://nasscom.in/about-us/what-we-do/industry-development/engineering-council, accessed April 15, 2024.

- ↩ Seth O’Farrell, “India switches to R&D”, Financial Times fDi intelligence, June 15, 2023. A Deloitte survey of 99 companies globally found that India is the destination of choice for multinationals’ R&D operations, and that 70 per cent planned to expand such work.

- ↩ Ibid.

- ↩ Anjan Das and team, MNCs R&D in India—A Glimpse, Confederation of Indian Industry, June 2017.

- ↩ Rishikesha T Krishnan, “India is an R&D hub for MNCs. Will global protectionism play spoilsport?”, Founding Fuel, November 2, 2019.

- ↩ “The IT industry, in particular, faces a severe crunch of quality manpower. They try to overcome the problem by introducing new curriculum, encouraging students to take up specialised courses, familiarising the students in specific toolkits at the teaching level, etc. They also provide incentives through scholarships, internships, and also through creating special faculty positions at the university/institution levels. From the study it emerge that the MNCs are not looking for knowledge advancement as their linkage with the educational institutions is for having access to human resources and to enhance the capability of human resources for their future requirement. So, MNCs are drawn to India to access human resources…” N Mrinalini, Pradosh Nath and G. D. Sandhya, “R&D Strategies of MNCs in India: Isolation or Integration?”, Economic & Political Weekly, March 31, 2012; also see Dhar and Joseph, op. cit..

- ↩ Rishikesha T Krishnan, op. cit.

- ↩ Ibid.

- ↩ https://www.glassdoor.co.in/Salaries/bpo-salary-SRCH_KO0,3.htm?trk=article-ssr-frontend-pulse_little-text-block

- ↩ “Staff turnover is decidedly a global challenge, but the problem is acute in India. The average global attrition rate for Q3 2021 is 20.4% for announced results…. we believe India’s attrition rate is far higher. Anecdotally, we hear that companies’ attrition rates in India are hovering anywhere between 30% and 50%, which is certainly higher than the last few years.” https://www.hfsresearch.com/research/it-bpo-industry-is-very-much-in-the-midst-of-a-talent-crisis-due-to-higher-attrition/

- ↩ Rajani X. Desai, “The Heritage We Must Enrich”, May 1993, reproduced in Women and Globalisation, 2004, RUPE.

- ↩ Jayati Ghosh, “Interrogating the holy grail of productivity growth”, real-world economics review, issue no. 96, 2021.

- ↩ Employment rate = employed persons as a ratio of persons of working age.

- ↩ “We were sitting on the couch outside Nilekani’s office, waiting for the TV crew to set up its cameras. At one point, summing up the implications of all this, Nilekani uttered a phrase that rang in my ear. He said tome, ‘Tom, the playing field is being leveled.’ He meant that countries like India are now able to compete for global knowledge work as never before—and that America had better get ready for this….“What Nandan is saying, I thought to myself, is that the playing field is being flattened .. . Flattened? Flattened? I rolled that word around in my head for a while and then, in the chemical way that these things happen, it just popped out: My God, he’s telling me the world is flat!“Here I was in Bangalore—more than five hundred years after Columbus sailed over the horizon, using the rudimentary navigational technologies of his day, and returned safely to prove definitively that the world was round—and one of India’s smartest engineers, trained at his country’s top technical institute and backed by the most modern technologies of his day, was essentially telling me that the world was flat— as flat as that screen on which he can host a meeting of his whole global supply chain. Even more interesting, he was citing this development as a good thing, as a new milestone in human progress and a great opportunity for India and the world—the fact that we had made our world flat!” Thomas L. Friedman, The World Is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-First Century (updated and expanded, 2007), p. 7.

- ↩ Dhirendra Gajbhiye, Rashika Arora, Arham Nahar, Rigzen Yangdol, and Ishu Thakur, “Measuring India’s Digital Economy”, RBI Bulletin, December 2022.

- ↩ Biswajit Dhar and Reji K. Joseph, “India’s Information Technology Industry: A Tale of Two Halves”, in K.-C. Liu, U. S. Racherla (eds.), Innovation, Economic Development, and Intellectual Property in India and China, ARCIALA Series on Intellectual Assets and Law in Asia, 2019.

- ↩ Sudip Chaudhuri, “Manufacturing Trade Deficit and Industrial Policy in India”, Economic & Political Weekly (EPW), February 23, 2013.

- ↩ Dhar and Joseph, op. cit.

- ↩ See Rahul Varman, Indian Telecom’s Spectacular Rise and the Nature of Monopoly Capital in India, Aspects of India’s Economy no. 80, https://rupe-india.org/aspects-no-80/indian-telecoms-spectacular-rise-and-the-nature-of-monopoly-capital-in-india/

- ↩ Sunil Mani, “Developing India’s Mobile Phone Manufacturing Industry”, EPW, May 9, 2020.

- ↩ Gajbhiye et al., op cit.

- ↩ Raghuram Rajan, Rohit Lamba and Rahul Chauhan, “Has India Really Become a Mobile Phone Manufacturing Giant?”, The Wire, June 1, 2023, https://thewire.in/trade/india-mobile-phone-manufacturing-giant-assembly

- ↩ T.V. Mohandas Pai, “PM Modi dazzles Silicon Valley”, Indian Express, October 2, 2015.

- ↩ Michael Kwet, “Digital colonialism: U.S. empire and the New Imperialism in the Global South”, August 15, 2018, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3232297 ; final version: Race & Class Volume 60, No. 4, April 2019.

- ↩ Social media: https://gs.statcounter.com/social-media-stats/all/india ; search engine: https://gs.statcounter.com/search-engine-market-share/all/india ; browser: https://gs.statcounter.com/browser-market-share/all/india ; mobile OS: https://gs.statcounter.com/os-market-share/mobile/india ; desktop/laptop OS: https://gs.statcounter.com/os-market-share/desktop/india/ ; e-commerce: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/india-business/amazon-puts-rs-1660-crore-in-indian-entity/articleshow/110130972.cms ; payments apps: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/tech/technology/paytm-upi-payments-drop-further-in-march-phonepe-google-pay-show-gains/articleshow/109167691.cms?from=mdr ; cloud services: Shouvik Das, “Microsoft India revenue rises 39% in FY23 on services boost”, Mint, October 20, 2023.

- ↩ Steve Ranger, “Linux just hit an all-time high share of the global desktop market—and surging popularity in India is driving uptake of the open source operating system”, ITPro., March 6, 2024, https://www.itpro.com/software/open-source/linux-just-hit-an-all-time-high-share-of-the-global-desktop-market-and-surging-user-numbers-in-india-are-driving-uptake-of-the-open-source-operating-system

- ↩ John Xavier, “Why is India’s Defence Ministry ditching Microsoft Windows for Ubuntu-based Maya OS?”, The Hindu, August 13, 2023.

- ↩ Figure for 2014 from Pitch Madison Advertising Report 2024; figures for 2023 from Varuni Khosla, “Ad spends to grow 11.8% in 2023 to reach ₹1.09 trillion”, Mint, December 14, 2023.

- ↩ Javed Farooqui, “Tech giants’ digital ad revenue surges 16% to Rs 55,000 crore in FY23”, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/tech/technology/tech-giants-ad-revenue-surges-16-to-rs-55000-crore-in-fy23/articleshow/106905402.cms?from=mdr There are some contradictions between different media reports regarding the figures of total ad revenues, but the broad picture is as stated here.

- ↩ Leah Nylen, “Zuckerberg and Google CEO approved deal to carve up ad market, states allege in court”, Politico, January 14, 2022, https://www.politico.com/news/2022/01/14/facebook-google-ad-market-lawsuit-527108

- ↩ Parliamentary Standing Committee on Finance, 53rd Report, December 22, 2022.

- ↩ Speech by Mukesh Ambani, 42nd Annual General Meeting of Reliance Industries, August 12, 2019.

- ↩ Jacqueline Hicks, “‘Digital colonialism’: Why countries like India want to take control of data from Big Tech”, https://theconversation.com/digital-colonialism-why-some-countries-want-to-take-control-of-their-peoples-data-from-big-tech-123048

- ↩ https://www.datacenters.com/providers/facebook , accessed May 20, 2024.

- ↩ https://www.google.com/about/datacenters/locations/ , accessed May 20, 2024.

- ↩ Leslie D’Monte, “India can become data capital of the world”, Mint, November 20, 2022.

- ↩ John Bellamy Foster and Robert W. McChesney, “Surveillance Capitalism: Monopoly-Finance Capital, the Military-Industrial Complex, and the Digital Age,” Monthly Review, July—August 2014.

- ↩ Ibid.

- ↩ BJP booklet on FDI in retail, October 2012,

- ↩ Press Information Bureau, Ministry of Commerce and Industry, “E Commerce Business Model”, December 11, 2019.

- ↩ “Received multiple complaints against e-commerce firms for violation of FDI: Govt”, Business Today, February 4, 2022.

- ↩ Bain & Company, How India Shops Online 2023, 2023.

- ↩ Deloitte, Future of Retail: Emerging Landscape of Omni-Channel Commerce in India, June 2023.

- ↩ “Under the Start Up India Initiative, action plan unveiled”, press release, Ministry of Commerce, August 2, 2023.

- ↩ “DPIIT recognises 1, 17,254 startups as on 31st Dec 2023”, press release, Ministry of Commerce, February 2, 2024.

- ↩ Rajas Saroy, Ashish Khobragade, Rekha Misra, Sakshi Awasthy and Sarat Dhal, “What Drives StartupFundraising in India?”, RBI Bulletin, January 2023.

- ↩ Weathering the Challenges: The Indian Tech Start-Up Landscape Report 2023, NASSCOM-Zinnov, 2023.

- ↩ “The Complete List of Unicorn Companies”, https://www.cbinsights.com/research-unicorn-companies

- ↩ Ibid.

- ↩ Saroy et al., op cit.

- ↩ Ibid.

- ↩ Ibid.

- ↩ Economic Survey 2022-23, p. 288.

- ↩ Amit Agrahari, “38% of India’s Unicorns are not ‘Indian’”, https://pn.ispirt.in/38-of-indias-unicorns-are-not-indian/

- ↩ Anuj Suvarna, “Almost 20% of India’s ‘100 unicorns’ headquartered overseas, few no longer unicorns”, https://www.vccircle.com/almost-20-of-india-s-100-unicorns-headquartered-overseas-few-no-longer-unicorns

- ↩ “[O]f the 40-odd already in the news as ‘acclaimed’ unicorns, 2 out of 3 have ‘flipped’ and are now incorporated overseas, with the Indian start-up a mere subsidiary to the foreign company. So these aren’t Indian anymore.” https://x.com/rahulsingh1966/status/1371287854345641986

- ↩ Crisis and Predation: India, COVID-19 and Global Finance, 2020; the relevant chapter also appeared in Monthly Review, September 2020 as “India, Covid-19, the United States and China”, https://monthlyreview.org/2020/09/01/india-covid-19-the-united-states-and-china/

- ↩ India’s industrial imports from China surged from $70 billion in 2018-19 to $101 billion in 2023-24. China is the largest supplier to India in all industrial goods categories, in several cases supplying over 70 or even 90 per cent of imports. The growth of electric vehicles and solar power portend even greater dependence on China. Global Trade Research Initiative, An Examination of India’s Growing Industrial Sector Imports from China, April 2024.

- ↩ Rahul Varman, op. cit., p. 60, citing an Oxford Economics study.