The economic and industrial structures of the capitalist countries have evolved dramatically; by the early 1990s, the share of the service industries in GNP had risen from 20-30% in the developed countries over a century ago, to 60-70% in those countries, 50% in the semi-developed countries and 34% in China. Trade in services has risen to 25% of the global trade volume and is expected to continue growing.

Since the service industries exert great influence over a country’s economic development and job market, we should devote increased effort to studying them from the perspective of economic theory. This is a complicated undertaking, because research into the theoretical aspects of the service economy still falls short of expectations, accompanied by wide and deep-rooted differences of opinion, in all schools of thought. This is because of the particularity of the service industries, the changes they are undergoing, and the growing universality of their scope.

Historical review of theories of the service economy

We shall now address the two main bodies of theory relating to the service economy: Marx’s, and those of Western scholars. Because of the differences in their research goals and subjects of study, they differ widely.

Marx’s theory of services

As noted, Mars made material goods production his main research area in his studies of the socioeconomic problems of capitalist societies in Capital, singling out the British textile industry for special treatment. He pointed out that the production of wealth by capitalist societies was characterized by large stocks of self-evidently tangible commodities. These could be accumulated over a long period of time, they could exist in the absence of producers and consumers, and they were transportable.

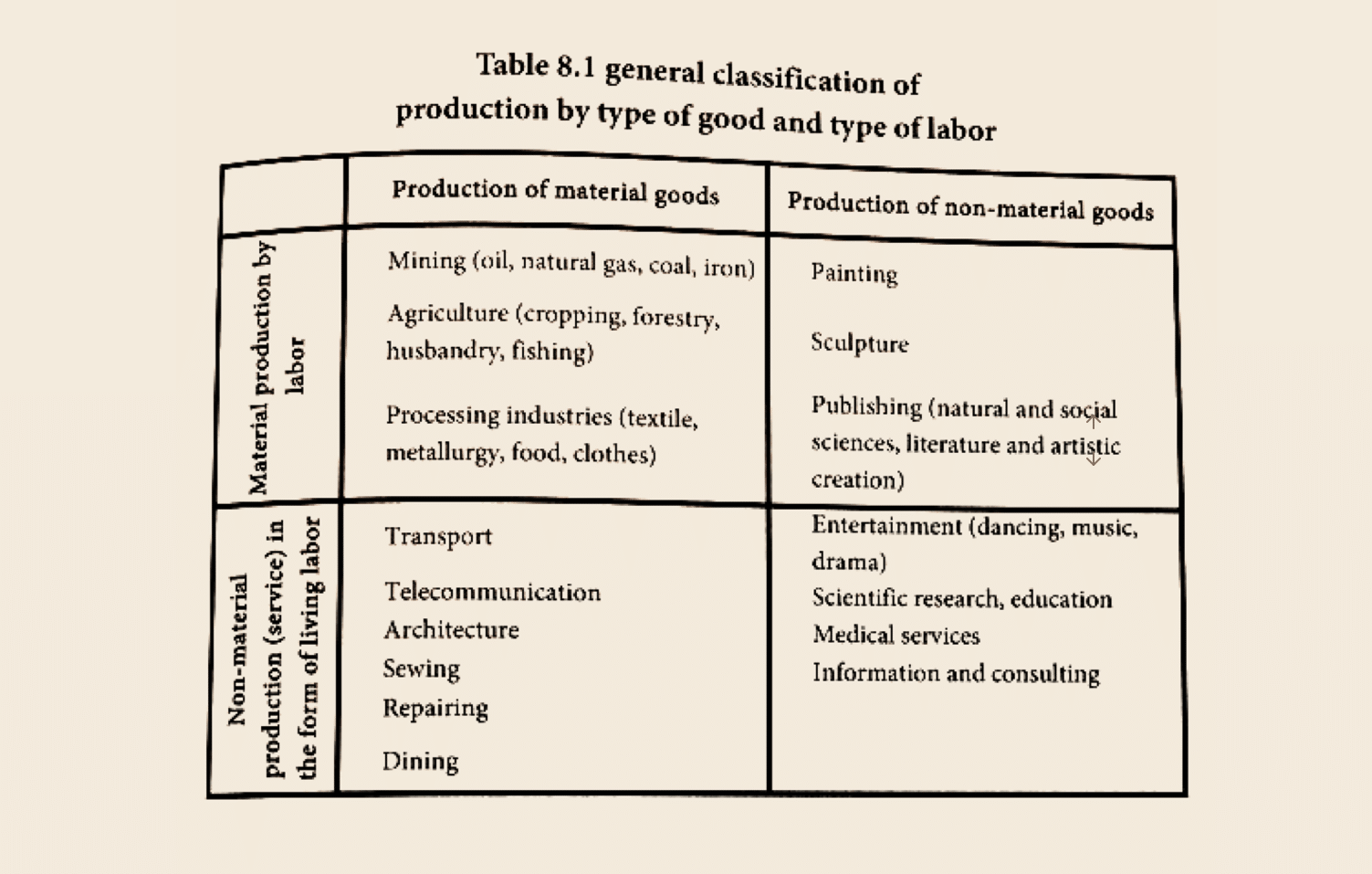

Products can be divided into material goods such as clothes, automobiles, and planes which exist independent of other factors, and non-material goods such as transport and communication, which exist in the form of living labor from which they cannot be separated. As Marx wrote, “in addition to the mining industry, agriculture and processing industries, we also have the fourth area of material goods production …. which was transport” (Marx and Engels 1972c, p. 444).

This suggests that transport can be classified in the same area as mining, agriculture, and processing whose purpose is to extract materials from nature. It does not actually produce or provide material goods, but creates products in the shape of living labor, which provide the intangible use value of changing the spatial location of material goods, so that these can be delivered to consumers as consumer goods in a real sense.

As we have noted, there are two types of non-material goods. The first consists of things like books or audiovisual products, which can exist in the absence of producers and consumers. The second take the form of living labor. These goods include live concerts and lectures. Both can be produced as commodities and become products of social labor by entering the exchange system. Marx argued that it was unscientific to define productive labor as that engaged in material production, an idea which he considered a one-sided outcome of Smiths outlook.

Table 8.1 provides a general classification of production based on the above analysis.

Full Article was an excerpted chapter from ‘The Creation of Value by Living Labour: A Normative and Emperical Study‘ by Cheng Enfu, Wang Guijin, and Zhu Kui.