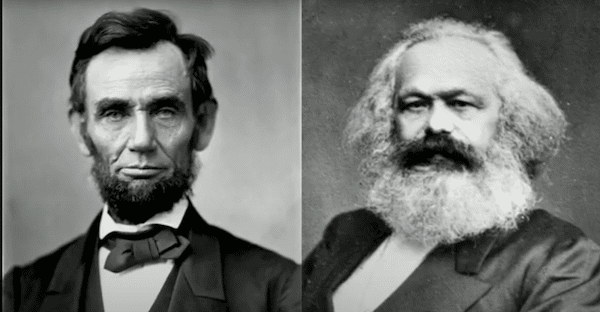

In 1864, Karl Marx and his International Working Men’s Association (the “First International”) sent an address to Abraham Lincoln, congratulating “the American people upon your re-election by a large majority.” As historian Robin Blackburn writes, “The U.S. ambassador in London conveyed a friendly but brief response from the president. However, the antecedents and implications of this little exchange are rarely considered.” It was not the first time Marx and Lincoln had encountered each other. They never met personally, but their affinities led to what Blackburn calls an “unfinished revolution”–not a communist revolution in the U.S.; but a potential revolution for democracy.

Lincoln and Marx became mutual admirers in the early 1860s due to the latter’s work as a foreign correspondent for The New York Daily Tribune. From 1852 until the start of the Civil War, Marx, sometimes with Engels, wrote “over five hundred articles for the Tribune,” Blackburn notes. Fiercely anti-slavery, Marx compared Southern planters to the European aristocracy, “an oligarchy of 300,000 slaveholders.” Early in the war, he championed the Union cause, even before Lincoln decided on emancipation as a course of action. Marx believed, writes Blackburn, that ending slavery “would not destroy capitalism, but it would create conditions far more favorable to organizing and elevating labor, whether white or black.”

“Marx was intensely interested in the plight of American slaves,” Gillian Brockell writes at The Washington Post. “In January 1860, he told Engels that the two biggest things happening in the world were ‘on the one hand the movement of the slaves in America started by the death of John Brown, and on the other the movement of serfs in Russia.’” Lincoln was an “avid reader” of the Tribune and Marx’s articles. The paper’s managing editor, Charles A. Dana, an American socialist fluent in German who met Marx in 1848, would go on to become “Lincoln’s ‘eyes and ears’ as a special commissioner in the War Department” and later the Department’s Assistant Secretary.

Lincoln was not, of course, a Communist. And yet some of the ideas he absorbed from Marx’s Tribune writings–many of which would later be adapted for the first volume of Capital—made their way into the Republican Party of the 1850s and 60s. That party, writes Brockell, was “anti-slavery, pro-worker and sometimes overtly socialist,” championing, for example, the redistribution of land in the West. (Marx even considered emigrating to Texas himself at one time.) And at times, Lincoln could sound like a Marxist, as in the closing words of his first annual message (later the State of the Union ) in 1861.

“Labor is prior to and independent of capital,” the country’s 16th president concluded in the first speech since his inauguration. “Capital is only the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed. Labor is the superior of capital, and deserves much the higher consideration.” That full, 7,000 word address appeared in newspapers around the country, including the Confederate South. The Chicago Tribune subtitled its closing arguments “Capital vs. Labor.”

Lincoln’s own position on abolition evolved throughout his presidency, as did his views on the position of the formerly enslaved within the country. For Marx, however, the questions of total abolition and full enfranchisement were settled long before the country entered the Civil War. The democratic revolution that might have begun under Lincoln ended with his assassination. In the summer after the president’s death, Marx received a letter from his friend Engels about the new president, Andrew Johnson: “His hatred of Negroes comes out more and more violently… If things go on like this, in six months all the old villains of secession will be sitting in Congress at Washington. Without colored suffrage, nothing whatever can be done there.” Hear the address Marx drafted to Lincoln for his 1865 re-election read aloud at the top of the post, and read it yourself here.