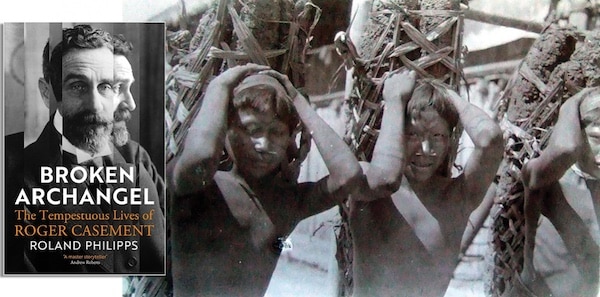

Broken Archangel–The Tempestuous Lives of Roger Casement; Roland Philipps

Bodley Head, £25

This thorough investigation of the life of Sir Roger Casement delves deep into the emotional waters of a man who lived a remarkable life and whose fame seems to grow with the passing years.

It was always going to be some story. Casement was an Irishman who rose from humble beginnings to the heights of the British diplomatic service at a time when Britain really did rule the waves. His achievements were such that he was knighted in 1912, retiring from the diplomatic service in July 1913 on a generous pension. Yet, just three short years later, the country that had honoured Casement was executing him for treason.

Author Roland Philipps does a good job in telling the story of the man who exposed Belgium’s imperial abuse in the Congo and further abuses, including slavery, by the Peruvian Amazon Company in the Amazon, and then became a fervent Irish republican.

It was the same passion for justice that drove his early exposés on behalf of the British government that led later to his efforts to secure an independent Ireland. He’d seen the damage caused by imperialism at first hand, and hence came the need to free his own people from under that yoke.

The subject of such a life is, not surprisingly, a conflicted individual. Philipps is constantly seeking to probe below the surface for answers. While very thorough in his approach, the reader is left wondering whether he really does nail his man.

Some of the arrangement of the book seems odd. He doesn’t reveal that Casement’s mother died when he was nine and his father three years later until 80 pages in. The author, instead, heads straight to the Congo and the diplomatic service in the early pages.

There is plenty of time given to Casement’s hidden homosexual activities, as recorded in his diaries. The diaries became an item of growing significance, particularly following his arrest and accusation of treason in 1916.

The selected use of the diaries to brief journalists and politicians prior to and after his trial show the British Establishment at its most duplicitous.

This deliberate act was done to help ensure Casement’s conviction, while also muddying his reputation worldwide in order to stave off dangers of martyrdom.

There have been accusations that the “black diaries” were fakes but Philipps comes down firmly on the side of authenticity.

As the years have gone by, with a now more tolerant society, the revulsion at what happened to this principled man has led to the very martyrdom that those shadowy British Establishment figures feared, being realised.

It has, however, taken a long time. Casement’s body was only disinterred from the grounds of Pentonville Prison in 1965 to return for an Irish state funeral in Dublin.

The author does a good job of getting below the surface of Casement. A man who was christened both Catholic and Protestant, dying the former, while fighting for Irish freedom.

It is also unclear whether the author likes Casement or not, which is probably sign of a good job, objectively done.

Stylistically, Casement’s early life up to 1913 is clear to follow, encompassing the Congo, the diplomatic service and the Amazonian exposé; less so the final three years.

There is a certain disjointedness in the sections on the time he spent in Germany trying to get support for independence and his failed effort to get weapons into Ireland for the Easter Rising. The reader is left wanting to know more.

Roland Philipps has certainly made a valuable contribution to a wider understanding and appreciation of Sir Roger Casement–a remarkable man–human rights activist turned Irish freedom fighter.

A long overdue appreciation of a true Irish hero.