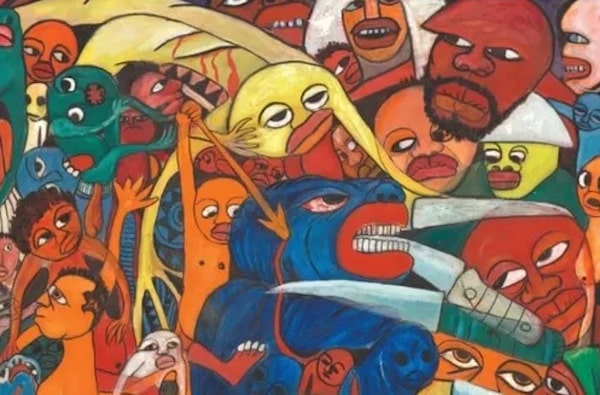

In April 2024, to coincide with the 50th anniversary of ROAPE and the 10th anniversary of www.roape.net, Ebb Books published Voices for African Liberation: Conversations with the Review of African Political Economy. The edited collection presents 38 interviews with African and Africanist socialists conducted by the Review of African Political Economy between 2015 and 2023, bringing to life older voices of liberation and lost radical histories alongside newer initiatives, projects, and activists who are engaged in the contemporary struggles to reshape Africa—to make, win, and sustain a revolutionary transformation in our devastated world. Here, we publish the book’s introductory chapter, which locates the volume’s conversations in ROAPE’s 50-year history providing radical analysis of African political economy.

In 1974, 50 years ago, the newly launched Review of African Political Economy (ROAPE) journal boldly announced its intentions in the first editorial, “Appropriate analysis and the devising of a strategy for Africa’s revolution must be encouraged and we hope that the provision of this platform for discussion will assist that process”. The question of what is to be done to change Africa’s capitalist underdevelopment was also answered, “an anti-capitalist class struggle … as a reminder that liberation is still on the agenda for most of the African continent”. The review was born in a period of great, radical hope. The continent, like the world, was being transformed not simply by the political and economic forces of capitalism, but by major social struggles. These counter-hegemonic movements were not only a challenge to this or that policy or discrimination—as great as these struggles were—but frequently to the entire social and political order.

In 1974, 50 years ago, the newly launched Review of African Political Economy (ROAPE) journal boldly announced its intentions in the first editorial, “Appropriate analysis and the devising of a strategy for Africa’s revolution must be encouraged and we hope that the provision of this platform for discussion will assist that process”. The question of what is to be done to change Africa’s capitalist underdevelopment was also answered, “an anti-capitalist class struggle … as a reminder that liberation is still on the agenda for most of the African continent”. The review was born in a period of great, radical hope. The continent, like the world, was being transformed not simply by the political and economic forces of capitalism, but by major social struggles. These counter-hegemonic movements were not only a challenge to this or that policy or discrimination—as great as these struggles were—but frequently to the entire social and political order.

The global 1968, as it is now described, played out in Africa as much as it did in Europe and North America. As South African-based writer Heike Becker told us in 2017, “students and workers in a range of African countries … contributed to the global uprising with their own interpretations, from Senegal and South Africa to the Congo, to mention just a few. Yet, those African revolts and protests have been forgotten in the global discourse of commemoration”. There were movements from below that joined up with and were part of the same energy for transformation and revolution felt across the world—even if they were generated by distinct dynamics.

By 1974, progressive change on the continent, which since independence had frequently come from above in the form of big state projects of change, had started to flounder. Even in Tanzania, once regarded as the Mecca of revolution, the project of ujamaa (cooperation, or familyhood) was beginning to spoil. To a generation who saw hope in Julius Nyerere’s and the Tanganyika African National Union’s (TANU) efforts to reverse a long, brutal history of colonial underdevelopment, cynicism had begun to emerge about the appearance of a new class of exploiters, a petty-bourgeoisie, or bureaucratic elite. Tanzania in 1974, where several founders of the review first cut their political teeth, was no longer the dynamic force it had once been.

Early state-led projects proclaiming socialism elsewhere on the continent had also started to fail or had been overturned. In Ghana, Kwame Nkrumah—the “father of African independence” and one of the main advocates of African socialism—had been overthrown in an American backed coup in 1966. In Guinea, Algeria, Egypt, and Congo-Brazzaville, left-leaning projects and the socialist politics of the first wave of independence were looking fragile, and often oppressive. Yet, independence was still being keenly fought for in large parts of the continent, and in these late independence movements, or second wave of liberation struggles, new and radical forces seemed to promise real independence, and a socialism grounded in each country’s specificities.

Samir Amin (2012), featured in the edited collection discussing ‘Revolutionary Change in Africa’. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

The first issue in 1974 was enthusiastic about these possibilities, noting in the editorial there were “valuable lessons for the mobilisation of popular forces throughout the continent, but also a specific determination on the part of the liberation movements and the peoples, notably in Guinea, Angola and Mozambique, not to settle for token independence and continued economic domination”. Or as Ruth First, one of the founders of the review, described in 1975 to her husband—Joe Slovo—after a visit to newly independent Mozambique, “I may say I’m thrilled to bits. Tanzania is one thing, but Mozambique! Wow”. Two years later, she moved to Maputo to contribute to the transformation of the country.

Frantz Fanon—the greatest theorist of national liberation—had argued in his 1961 classic, The Wretched of the Earth, that only in armed struggle was real liberation a prospect. So, it was to these new, second phase liberation struggles—which had seen hard and long armed resistance to colonial occupation—that the hopes of socialism and transformation could be firmly pegged. Amílcar Cabral, the great leader of Guinea-Bissau’s late independence, saw in the earlier wave of struggle the inherited state as the central failure: “It’s the most important problem in liberation movements. The problem is perhaps the secret of the failure of African independence”.

By the mid-1970s, the first issues were being written, copyedited, typeset, then collated, folded, and put into hand-addressed envelopes and sent around Africa, to liberation movements, political prisoners—including smuggled to African National Congress (ANC) and South African Community Party (SACP) prisoners on Robben Island, wrapped in Christmas paper!—and to universities and activists around the world.

The journal—or the “new platform” as it was described in the first editorial—was enthralled by Guinea-Bissau’s independence in 1974 along with Angola and Mozambique the following year in 1975, countries that seemed to promise real liberation and socialist transformation in the victory against Portuguese colonialism. ROAPE saw itself as a fraternal, broad, though Marxist platform, supporting these movements and helping, where possible, with the exceptionally difficult issues of socialist development. Yet this was not a scholarly activity, far from it. As the first editorial pointed out, “merely providing an alternative analysis could be … emptily ‘academic’. It is hoped therefore that our contributors will also address themselves to those issues concerned with the actions needed if Africa is to develop its potential”.

Agency was vital, with a range of questions being asked about the subjective factors of liberation. Among the questions the review posed were what role was there for the state? Could it be wielded for radical change? What about the development and role of popular classes in political change? Who powered the new movements on the continent, and was there a viable socialist project in the renewed struggles for national liberation? What role did the working class play, were they the agents in the projects for socialist reconstruction or the recipients of reforms from above?

Nnimmo Bassey (2012), featured in the edited collection discussing ‘Extraction-Driven Devastation’. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

In these early days these questions were vital. They could be seen in the debate between Ruth First and [anthropologist] Archie Mafeje in ROAPE’s pages in 1978 about the meaning of the Soweto uprising in 1976 in South Africa, or in the discussions on the intervention of Cuban forces in Angola from 1975. The Cuban intervention was celebrated by some at the review while others remained sceptical. Were Cuban troops not in Angola to make sure the oil (and profits) from American owned rigs in Cabinda continued to flow? As part of this security detail, Cuban troops were required to repress striking workers. The contradictions abounded, and arguments raged on.

ROAPE was also clear about its role in providing a forum for the debates on the frailty of socialist projects from above, intended as direct interventions which could explain and assist the movements and new governments attempting to challenge the continent’s underdevelopment. Many of its early members—John Saul, Peter Lawrence, Ruth First, Robin Cohen, Mejid Hussein, Duncan Innes, Mustafa Khogali, Katherine Levine, Jitendra Mohan, Gavin Williams—were militants in these new projects, in one way or another. Yet, in these years there was always a tension at the heart of the review’s radical endeavour. A tug of war between state-led, top-down projects for socialist change, and class struggle—in the strikes and workers’ occupations in Tanzania in 1973, the strikes of oil workers in Angola, or the uprisings across South Africa after 1976, for example—empowering change from below. This tension, from above or below, remains alive in ROAPE today.

In 2014, the Editors of ROAPE wanted to connect to a new generation of radicals on the continent and elsewhere, who were involved and interested in socialist politics and revolutionary change. The connection was a homecoming for the journal, where the Review’s heart had always been, but to some extent we had become lost in the thicket of academia and publishing. Many barriers stood in our way: paywalls that locked down our content, academic grants, career advancement and research assessments, and the deadweight of post-structuralism. Yet much was with us. The spirit of the period contained prodigious revolutionary energy, in the celebrated and tragically defeated struggles in North Africa and the Middle East, but also in the almost entirely unreported revolutionary wave further south—most remarkably in Burkina Faso, Nigeria, and Senegal.

Roape.net was launched in 2014. For a decade, roape.net has been a forum for radical commentary, analysis and debate on political economy and the vibrant protest movements and rebellions on the continent. One of the most exciting areas of the website has been our interviews. These interviews—perhaps more than any other part of the website—bring to life older voices of liberation, frequently hidden, or lost histories, and newer initiatives, projects and activists who are engaged in the contemporary struggles to reshape Africa: to make, win, and sustain a revolutionary transformation in our devastated world.

Esther Xosei (2017), featured in the edited collection discussing ‘Afrika and Reparations Activism in the UK’. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

In the pages that follow, we present an edited selection featuring 38 of these interviews conducted between 2015 and 2023, organised into three parts. The first part, Lessons from the Past, focuses on historical movements, figures, and periods—from Walter Rodney, Amílcar Cabral, and Steve Biko to Ghana, Senegal, and Tanzania in the 1960s and 1970s, and beyond—as part of the vital process of learning from past defeats and victories to inform contemporary struggle.

The second part, Weapon of Theory, should not be mistaken for abstract theorising. On the contrary, the section features conversations with organic intellectuals and committed scholar-activists of national and international renown whose prime focus and concern is on developing theory from real-world observation to inform revolutionary struggle and transformative change. As Amílcar Cabral said in his speech of the same title, delivered in 1966 to the first Tricontinental Conference of the Peoples of Asia, Africa and Latin America held in Havana, “every practice produces a theory, and [if] it is true that a revolution can fail even though it be based on perfectly conceived theories, nobody has yet made a successful revolution without a revolutionary theory”.

The third and final part, Militants at Work, covers a range of contemporary anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist struggles, as told by those directly involved. It moves from Shell Oil in Nigeria, anti-imperialism in Senegal, and reparations activism in the United Kingdom, to food sovereignty in Kenya and North Africa, campaigning against patriarchal oppression in Tanzania, and crisis and resistance in Zimbabwe. The full archive of interviews, along with all other material on the site, can be found at www.roape.net.

Voices for African Liberation: Conversations with the Review of African Political Economy is available to order through the Ebb Books website.

Leo Zeilig is a writer and researcher. He has written extensively on African politics and history, including books on working-class struggle and the development of revolutionary movements and biographies on some of Africa’s most important political thinkers and activists. Leo also writes political fiction.

Chinedu Chukwudinma is a socialist activist and writer. He writes on African politics, popular struggles, and the history of working-class resistance on the continent. Chinedu has written extensively on the Guyanese revolutionary Walter Rodney.

Ben Radley is a lecturer at the University of Bath. His research interests relate to the political economy of development in Africa, with a focus on resource-based industrialisation, green transitions, and labour dynamics. He is the author of Disrupted Development in the Congo.