“Right now, we stand here as men who refute their Jewishness and the Holocaust being hijacked by an occupation which has led to conflict for so many innocent people.” The anguish expressed in this 60-second acceptance speech at the 2024 Academy Awards by Jonathan Glazer, the director of The Zone of Interest, sparked great acclamation from critics of the violence perpetrated by the Israeli state, as well as venomous outrage on the part of Israel’s supporters.

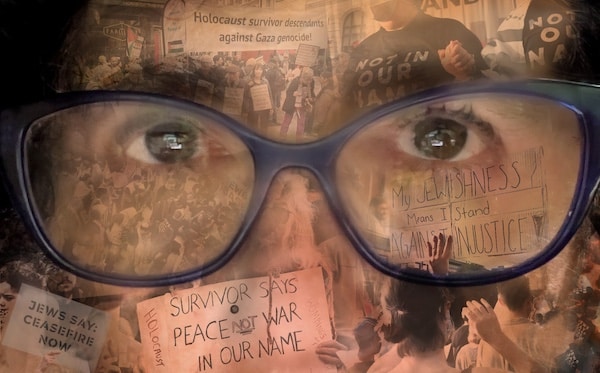

As a child of Holocaust survivors and a scholar of Holocaust memory and its transgenerational transmission—a process I have discussed as “postmemory”—I am not surprised by how prominently the specter of the Holocaust has loomed in the aftermath of the attacks by Hamas of October 7, 2023. Still, the radical discord about the longstanding effects of the Holocaust and the virulence of the debate over its meaning have given me pause. The outcry against Jewish artists like Glazer has been so extreme and despairing that I feel I must pay attention to it, even if such outrage appears, at times, to be manipulated and disingenuous.

The concern about the ideological misuse of Holocaust memory that Glazer bemoans is not a new phenomenon. Prominent Jewish survivors and intellectuals like Jean Améry, Primo Levi, Zygmunt Bauman, and, of course, Hannah Arendt condemned the use of the memory of the Holocaust for the state of Israel’s political purposes. Yet the misappropriation they warned against has only been amplified after October 7: Israeli politicians and the media have repeatedly and increasingly equated Hamas with Nazis, as well as called Palestinians “human animals,” recalling Nazi rhetoric against Jews. Absurdly, some have called Jews who support Palestinian liberation “Kapos.”

This current weaponization of the Holocaust and of antisemitism is something that I have contested, along with colleagues from the field of Holocaust studies. Of particular concern is how such weaponization authorizes retaliatory, eliminationist violence even if under the guise of security and self-defense.

But there is something that those of us in this field have not yet done. We have not considered how the approaches to the memory of the Holocaust that predominated in our own scholarship and pedagogy for several decades have left a space for its ideological and political misuse. Might the structures of remembrance our work has featured also have fueled the kind of existential fear of the Holocaust’s return that we are currently witnessing?

I am thinking, in particular, of how the focus on severe trauma has long dominated a potentially exceptionalist understanding of Holocaust victimization, as well as the powerful ways in which trauma has been transmitted across multiple generations. To inherit the legacy of the Holocaust in the second, third and subsequent generations—many have claimed—is to suffer from transgenerational trauma.

That is not how I have meant “postmemory” to be understood. But now I find myself rethinking earlier assumptions.

Individual acts of survivor witness have been collected in video testimony archives since the 1970s and have widely influenced Holocaust pedagogy at both secondary and college levels. The extreme psychic injury movingly expressed in some of these accounts has also influenced the aesthetic choices of Holocaust art, including film, literature, visual art, music, museology, and memorialization, inviting empathy and identification. Some second and third generation writers and commentators—those who are currently amplifying fears of rampant antisemitism and evoking the phantom of Holocaust destruction in hyperbolic ways—are also the ones who attended school and college just when Holocaust and trauma studies were developing.

In what ways does their current panic hark back to the trauma-driven memory that some of us in the field might have enabled?

Over the last decade, the study and practice of cultural memory and memorialization have shifted—acknowledging the deep traumatic injuries left by painful histories of enslavement, colonialism, racism, war, and genocide, but also modulating their scope. To be sure, Holocaust victimization remains an ever-present subject. In some popular cultural and also scholarly venues, moreover, what Alisa Solomon has recently called the “lachrymose” approach to Jewish history leading back to the Holocaust is enduring. Within the field of memory studies, however, the centrality of the Holocaust as a universal signifier and limit case has largely changed. Today, memory studies focuses on comparative, multidirectional, and connective methodologies that relate, without conflating, distinct historical catastrophes, while also granting each its own historical specificity and evolution.

At the same time, memory scholars and many artists have been trying to contest the inevitability of traumatic return that leaves those affected by violence, along with their descendants, forever as victims, forever vulnerable to repetition—whether psychic or material. A turn toward practices of communal healing and repair has occasioned activist interventions in the interest of preventing further violence and envisioning a more just, interconnected future. Importantly, these methodologies have made it imperative, for example, to connect the memories and postmemories of the Holocaust and the Nakba, connections that are essential to what Edward Said called the “bases for coexistence.”

But in the crisis after October 7, the paradigm of trauma has regained momentum, both through its own historical and affective persistence and through political and media-driven manipulation and exploitation. The lens of compounded trauma has magnified a vision of uniqueness that, in Omer Bartov’s terms, “extracts [the Holocaust] from history.” And it feeds the reactivation and contagion of unruly affects like fear, terror, guilt, and rage: revealing the reactionary potentials of transgenerational memory.

What, then, is the responsibility of those of us who might have contributed—however inadvertently—to the tenacity of this trauma-dominated version of Holocaust memory?

The testimony of witnesses has been central to how the Holocaust is remembered, as French historian Annette Wieviorka showed in her 1998 book L’ère du témoin (The Era of the Witness). Immediately after the war, numerous hidden and buried testimonials by victims were recovered, and many survivors were interviewed. However, the “advent of the witness” did not occur on a global scale until the Jerusalem trial of Adolf Eichmann in 1961.1

This first televised trial was meant to serve broad pedagogical purposes, exposing viewers around the globe to the ultimate evil of a Nazi perpetrator sitting in a glass box. But it was also meant to feature the embodied survivor-witnesses who, in Wieviorka’s terms, became “bearers of memory”—narrating and acting out their devastating experiences on the stand. Tellingly, Hannah Arendt—who reported on the trial for the New Yorker and later published her dispatches in Eichmann in Jerusalem—was critical of how the Jewish state instrumentalized victim suffering into a tool of nation-building.

It was not until the 1980s and 1990s, however, that the voice of the witness “from inside the event” (in the terms of the survivor psychoanalyst Dori Laub) became the primary source for attempting to understand the Nazi genocide. But it also became the way to understand the workings of trauma more generally: its injury of psyche and soul, its seeming incurability and inevitable repetition, its transmissibility across generations.2 This coincided with the DSM-III’s first entry on post-traumatic stress disorder in 1980 and sparked a growing multidisciplinary scholarship on the effects of trauma on remembrance and transmission. It is true that some key works on trauma as a multipronged field of knowledge production by Judith Lewis Herman (1992) and Cathy Caruth (1995), for example, were daringly comparative—showing similar effects in the experiences of child sexual abuse, wartime suffering for soldiers and civilians, nuclear destruction, and more.

Still, the Holocaust became fundamental to the study of trauma. And, at the same time, trauma became essential to studying the Holocaust.

And how could that not be? After all, witness testimony has the potential to “burn through the ‘cold storage of history,’” explained Geoffrey Hartman, one of the founders, in 1979, of the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies.3 Watching and teaching footage from the Eichmann trial and subsequent video testimonies collected in archives, we could not only study the events of the past but also observe how their memory lives on in the individual body, and is communicated to listeners and descendants.

It was in this spirit of embodied remembrance and traumatized speech that Claude Lanzmann’s 1985 film Shoah soon became a staple of Holocaust remembrance and pedagogy. Consisting of nine and a half hours of witness testimonies, Lanzmann’s film enabled viewers and students to hear and see on screen fractured testimonial accounts emerging from within the remembering body and voice. In a few uncanny scenes, survivor and bystander witnesses no longer merely narrate the past but literally seem to be back inside it. In these moments of muteness—in which the witnesses’ mouths literally dry up and can no longer utter words and sentences—memory gives way to what Lanzmann calls “incarnation,” illustrating the paralyzing effects of the past’s seemingly inescapable traumatic return in response to present triggers.

It is these moments, also, that the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben highlights in his influential 1999 book Remnants of Auschwitz: The Witness and the Archive, asserting, in a reading of Primo Levi, that “the one who cannot bear witness” is the “true witness,” enacting “humanity at its limits.”4

Testimony archives illustrate the need for memory and affect to supplement historical documents, so as to produce a more encompassing understanding of the past—not just what happened, but also how it continues to be transmitted. But, as the work of Holocaust scholars like Dominick LaCapra, Thomas Trezise, Sidra DeKoven Ezrahi, and my own in collaboration with Leo Spitzer, have cautioned over the years, featuring muteness as communicating more than speech comes with considerable dangers of mystifying the Holocaust.

Staying with the enormity and unspeakability of these histories risks obscuring the voices of those witnesses who, committed to passing it on for the future, do tell their story as best they can. It risks privileging utter victimization, thus obscuring moments of resilience, courage, and ingenuity that enabled survival. And it risks precluding the possibility of therapeutic listening in the interest of healing and repair.

Powerful affect, moreover, lends itself to uniqueness and exceptionalism that draw readers, viewers and students into a traumatic past, which can then highjack the present. Many post-Holocaust works invite us to identify and, indeed, to allow ourselves to be traumatized. But this invitation risks contributing to, and authorizing, the ongoing sacralization that the Holocaust has acquired in cultural memory.

This is why it is especially important, after October 7, to recognize the dangers of building Holocaust memory on victimization alone. For if we only remember the Holocaust through extreme trauma, then, in turn, we allow the Holocaust to continue to serve as the privileged site for the study of traumatic injury, isolating it from history.

POSTMEMORY

The evolution of the trauma paradigm defining Holocaust remembrance—as well as the shifting pedagogical, scholarly, and aesthetic choices that have emerged to reflect it in literature, art, memorials, museums, and syllabi—are largely the work of my generation. That is, they are the work of descendants of survivors.

Many of us scholars, teachers, and artists came to the work on trauma and memory with our feminist, antiracist, anticolonial, and antimilitary commitments. The turn to the past, for us, was part of an intellectual and political project dedicated to critiquing and enlarging the present, to contesting official histories, and to making space for suppressed or forgotten voices that might enlarge the historical archive. But for some of us this turn was also personal.

In my own case, there were times when my parents’ memories of surviving the war in collaborationist Romania felt more real than my own childhood memories. They felt more real even though, as for other familial descendants, they were transmitted incompletely and indirectly: leaving space for imaginative investment, projection, and creation. For us, these were not memories, but what I have described as postmemories: powerful and vivid, yet belated and mediated, temporally and qualitatively removed.

The weighty inheritance of such extreme trauma came with an important caveat, however—the consciousness that, no matter how immediate it feels, no matter how much we identify and empathize, our postmemory is vicarious. We are not, as many erroneously insist, second-generation survivors: we are descendants of survivors.

It can be easy to forget that, although it could have been me, importantly and decidedly, it was not me—it was their story and not ours. Our postmemories do not grant us the status of victims.

Have we insisted on this distinction forcefully enough? The unmediated reenactment of inherited trauma, whether familial or collective, that manifests itself in the fears of annihilation expressed by many Jews in the aftermath of October 7 would suggest not.

Memorial artists, writers, and museologists have developed a compelling postmemorial aesthetic, which reflects the complex, contradictory, and multiply mediated elements of this structure of transmission. They evoke the haunting that ensues in the aftermath of trauma and the pull to relive it. Yet, the gaps in knowledge and understanding, the silences and fractures that characterize this aesthetic, acknowledge the unbridgeable distance of such extreme experiences, even as they provoke an urge to learn more and to understand. Postmemorial works engage readers and viewers in acts of mourning for a lost world, in impulses to repair the loss and heal those who have suffered it, while at the same time recognizing the unbridgeable disconnection of the aftermath.

Maus (1986 / 1991) is the now classic work of the second-generation artist Art Spiegelman. And Maus is a great example of a text that modulates familial proximity to the victims with unbridgeable distance, identification with disavowal. Spiegelman cautions against easy identification with this history of victimhood and demonstrates its risks. When his character wears a concentration camp uniform, he has a mental breakdown. When he draws himself as a mouse, he is back inside, a terrified child. His own generational distance is signaled by the mouse mask that can be removed. But sometimes the smoke from the crematorium chimneys comes into his drawing studio, merging with the smoke from his cigarette.

This conflating of the present with the past that Spiegelman shows with the image of the smoke is something Edward Said warned against decades ago when he wrote, in The Question of Palestine, “there can be no way of satisfactorily conducting a life whose main concern is to prevent the past from recurring. For Zionism, the Palestinians have now become the equivalent of a past experience reincarnated in the form of a present threat. The result is that the Palestinians’ future as a people is mortgaged to that fear, which is a disaster for them and for Jews.”5

After October 7, we are seeing how, at moments of crisis and danger, the phantom of the Holocaust can resurface to reactivate trauma in Jewish communities for those who were there. But we are also seeing how it activates inherited trauma for those who, decidedly, were not there.

Contagious among persecuted groups, transgenerational trauma and the resulting dread can easily be amplified and exploited. But, as real as they might feel, we do need to ask whether these fears emerge from actual memories, or postmemories, of the Holocaust or of Nazism or whether they are vicarious “Holocaust effects” that act like memories (to use a term coined in the 1990s by the scholar Ernst van Alphen to describe post-Holocaust art). As symptoms, they resurrect a past, even a long past, catastrophe in groups that are still haunted by it.

I do not, in any way, deny the existence and growth of global antisemitism, nor the phenomenon of lasting indirect or compounded transgenerational trauma. But we must be aware of how the contagion driving these phenomena can lead to the perpetuation of a culture of defensiveness and denial, of racialized hatred, nationalism and ethnocentrism that can only result in further violence. We must be aware of how the inherited trauma we have ourselves studied and theorized can make it difficult to perceive and acknowledge larger contexts and the suffering of those deemed “other.” Most immediately, as the trauma paradigm persists for Jews, it is Palestinians whose inherited and ongoing trauma of expulsion and dispossession is made invisible and whose lives are deemed less precious and, in Judith Butler’s terms, less “grievable.”6

In recent years, however, it is precisely these larger contexts and the responsibilities they have spawned that have come to shape memory studies and its commitment to social justice. Comparative, multidirectional, and connective approaches to memories of painful pasts have certainly brought the insights and theories of trauma and witnessing drawn from Holocaust testimony to other historical catastrophes. But they have also enjoined us to revisit the trauma suffered by Holocaust survivors and to find alternative stories and representations contained in their accounts.

Importantly, the moments of resistance and resilience—as well as possibility, potentiality, and even hope that have emerged in the stories of survivors of enslavement, dictatorship, gender-based and racialized persecution—have helped Holocaust scholars and artists reimagine the exclusive focus on trauma and its inexorable aftereffects. To come back to Maus, as one instance, the story of Anja Spiegelman, the mother, need not be seen exclusively as one of victimization, suffering, and suicide as told by Vladek and Artie. We can go back to a few scenes that suggest a different story of Anja’s activism in the resistance and her participation in a network of activist women in Auschwitz.

Thus, individual and collective accounts can be reread and even reimagined. In so doing, Holocaust memory can participate in the practices and discourses of accountability, justice, care, mutual aid, and repair; practices that aim to resist trauma’s unforgiving return and to create different memories to pass down to future generations. Such a relational memory of the Holocaust that contests the inevitability of continuing trauma was beginning to take shape, only to be halted in the response to the violence of October 7.

AFTER OCTOBER 7

Why continue to teach the Holocaust? Why continue to build and visit Holocaust memorials and museums? What lessons do they offer our present and future—now, after the attacks of October 7 and in the midst of the genocidal devastation in Gaza?

For survivors and the generations born after, it has been, in large part, to practice an ethos of “never again,” not just for Jews, but for everyone. Although this universalizing vision of Holocaust memory has certainly eroded over the last decades, we now see “never again” serving as a uniquely ethnonationalist Israeli reaction formation to October 7 that fuels defensiveness and disavowal, paranoia, and renewed cycles of violence.

It is only when “never again for anyone” becomes a rallying cry for justice and possibility that we can assume responsibility to, in Judith Butler’s terms, “preserve the life of the other.”7 A relational understanding of memory based on a shared, if differential, embodied vulnerability elicits different demands across subjects and generations—not so much the identification and empathy we have learned from Holocaust trauma, for some repeated on October 7, 2023, but, in a more activist vein, forms of co-witnessing, solidarity and co-resistance that also grant distance and difference.

The acknowledgment of vulnerability rather than demands for inviolability and permanent security would entail a pedagogy that engages with memory relationally. That pedagogy would have to include the legacy of the Nakba and the costs of Jewish settlement in Palestinian lands in the aftermath of the Holocaust. At this moment, I cannot imagine a course on the Holocaust that would not include reflections on a Palestinian narrative following from the Nakba and acknowledging its continuity.

The Holocaust has inspired a postwar regime of what has come to be called “transitional justice,” not only by way of trials, but by what Pankaj Mishra, in his article on “The Shoah After Gaza,” calls the “edifice of global norms built after 1945. … [I]n the absence of anything more effective,” he writes, “the Shoah remains indispensable as a standard for gauging the political and moral health of societies.” Mishra believes that the Shoah’s “moral significance” could be rescued if the present calamity is acknowledged. Yet if we recognize how Palestinians have been left out of this evaluation of the “political and moral health” of postwar societies, and how the present war is being waged in the narrow interest of “never again” for an ethnonationalist Israeli state alone, I doubt that the Holocaust could ever serve as a “universal reference” again, if it ever did.

The numerous and increasing links between the Holocaust and the attacks of October 7 conflate the extremity of one with the extremity of the other, as Enzo Traverso among others has argued. Echoing the fear of Holocaust denial, for example, as Linda Kinstler has shown, the “Israeli campaign for memory” of October 7 amasses and disseminates visual evidence and testimony, not “as a means of ‘truth-telling,’ but … instead as material for hasbara, which literally means ‘explanation’ but practically means ‘propaganda.’” These links become institutionalized when, for example, the USC Shoah Foundation expands its archive of Holocaust survivor testimony by interviewing survivors of the October 7 attacks in their immediate aftermath.

The characterization of the Holocaust as the crime of all crimes—one that is always in danger of being displaced or denied—impedes, rather than clarifying, an understanding of other genocides, and of the genocidal character of the war in Gaza.

SOLIDARITY

I am writing this amid immeasurable trauma suffered by Gazans faced with destruction of their lives and life-worlds and enduring starvation and death, and by Palestinians in the increasingly violent West Bank. It is hard to imagine how this complex compounded trauma can be addressed and worked through and how it will it be transmitted to future generations.

What conditions, what kind of structure of care in the form of a “safe and supportive ‘container’”—to use the phrase of psychoanalyst and trauma expert Bessel van der Kolk—will be needed to confront this devastation and envision a sustainable future for Palestinians?8 What forms of accountability and justice could enable a communal coming to terms with these crimes? And, also, in view of the ways in which they have all been amplified, politically weaponized, and placed under the shadow of the Holocaust, how will the violence of October 7, the plight of Israeli hostages, and Israel’s responsibility for genocide in Gaza be worked through, remembered and transmitted? These tasks appear more overwhelming and intractable with every passing day.

One lesson we have learned from the violence of the 20th and 21st centuries, of which the Holocaust was a part, is that our futures depend on a confrontation with painful and traumatic pasts, not as victims but as world citizens in solidarity with others. Confronting the traumas we have inherited in this way is a first step toward enabling their transformation in the present and for the future.

The postmemory of the Holocaust can be useful at this moment. But that is true only if those of us who have a stake in it refute, in Jonathan Glazer’s terms, the inevitability of continued victimization, and refuse to allow our histories to be used as an alibi for war and destruction. It can only be useful if the Holocaust’s postmemory is viewed in relation to other violent and genocidal histories, and not as external to or exceeding them. Each, in its own specificity, can gesture toward a possible future after such ruin. That said, the current and longstanding history of violence in Palestine will need its own structures of liberation and justice, community building and healing.

I can only speak for the responsibility of Jews who have lived with the legacy of the Holocaust. As the postmemory generations, we might begin by acknowledging how, inadvertently perhaps, we have ourselves perpetuated an image of Jewish victimization that has contributed to the present defensiveness that takes the form of aggression. Let us use our painful inheritance in the interests of justice and solidarity with Palestinians whose lives are being destroyed.

Violent histories can be simplified in their aftermath. It is up to us to ensure that this moment will be remembered and transmitted as one not only of devastation, but also of activist solidarity and co-resistance—leaving a space for hope.

Notes:

- ↩ Annette Wievorka, The Era of the Witness, translated from the French by Jared Stark (Cornell University Press, 2006), pp. 56—95.

- ↩ Shoshana Felman and Dori Laub, Testimony: Crisis of Witnessing in Literature, Psychoanalysis and History(Routledge, 1992), pp. 75—92.

- ↩ Geoffrey Hartman, The Longest Shadow : In the Aftermath of the Holocaust (Indiana University Press, 1996), p. 142.

- ↩ Giorgio Agamben, Remnants of Auschwitz: The Witness and the Archive, translated from the Italian by Daniel Heller-Roazen (Zone Books, 1999), pp. 41—86.

- ↩ Edward W. Said, The Question of Palestine, (Times Books, 1979), p. 231.

- ↩ Judith Butler, Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable, (Verso, 2009).

- ↩ Judith Butler, The Force of Nonviolence: An Ethico-Political Bind, (Verso, 2020).

- ↩ Bessel van der Kolk, The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma (Penguin, 2014), p. 302.