When I first snorkeled off of Key West as a teenager back in 1966, Florida’s coral reef was estimated to have 90 percent live cover—a multi-hued array of fan, brain, pillar and elkhorn corals, shoaling fish, grazing sea turtles, and hammerhead sharks that stretched from Palm Beach to the Dry Tortugas seventy miles west of Key West.

Coral reefs are unique, complex, and harbor one of the most biologically diverse ecosystems on Earth. They were formed by underwater ridges built up over thousands of years on the exoskeletons of multiple generations of coral polyps, a marine animal that spawns once a year. But when that top living layer of the reef dies, it all begins to erode away.

The two largest coral reefs today are Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, stretching over 1,600 miles (it is the largest living object that can be seen from space), and the 700-mile-long Mesoamerican reef off of Central America. Then there was Florida’s at 350 miles.

“The Florida coral reef track used to be the third largest reef but when you have 2 percent live coral cover—by textbook definition you are no longer a coral reef. It’s an algal turf reef now but not a coral reef. That’s gone,” says Dr. Sarah Frias-Torres, an oceanographer and marine ecologist with the Smithsonian (but speaking on her own behalf) who has studied the Florida reef and its wildlife for over two decades.

“It’s been a death by a thousand cuts,” she explains.

The latest heat wave—in 2023, when water temperatures hit 101 degrees—cooked the corals alive. They didn’t even go through a bleaching phase. There are still hot spots [patches] of good live coral cover but there are more corals alive now in ocean and land-based nurseries [being grown by coral restoration groups] than in the actual reef tract.

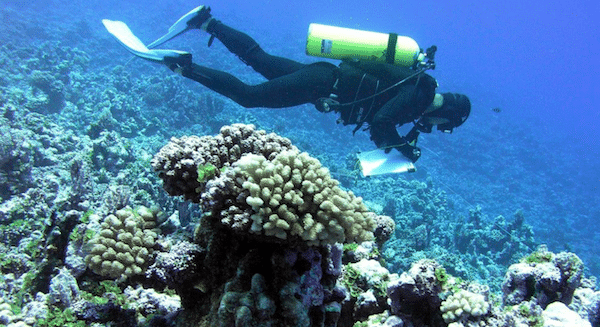

A scuba diver surveys bleached corals in the U.S. Virgin Islands.

I’ve heard a similar story from other ocean scientists and government officials about the dead coral reef, although some prefer terms like “highly degraded.”

Of course, the physical structure of the 10,000-year-old reef remains intact, and since the structure attracts fish, much marine wildlife remains to attract tourists—a $2.3 billion annual industry in the Keys—at least for a few more decades.

And because of shifting baselines— the idea that people believe what they see today is the standard for what has always been—many visitors jump off snorkel boats flying Budweiser flags and think they’re viewing an authentic coral reef. But it’s more like entering a cemetery and thinking you’re in Sherwood Forest.

The loss of Florida’s reef can be traced to the decline in water quality and clarity from coastal development, runoff of sediment, fertilizers, pesticides and sewage, urchin and coral diseases (the worst—Stoney coral tissue loss disease—was first identified during the dredging of the Port of Miami), physical impacts from boats and divers, algal blooms, overfishing, ocean acidification, and ocean warming.

Attempts to limit the loss through restoration of the Everglades, whose waters feed onto the reef, and the declaration of a Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary in 1990 have done little to turn the tide. Coastal developers and Big Agriculture (in this case, the sugarcane and citrus industries) continue to pollute the Florida Statehouse and governor’s mansion, preventing any serious action to save the reef.

There are now two ways to move forward: We can either use resiliency and restoration models based on nature, or we can do nothing and remain in a state of denial.

Scientists maintain corals growing in a coral reef nursery. The coral fragments will later be used to restore a degraded reef.

First up, denial: In May, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis signed a bill that erases the words “climate change” from state laws and regulations following the hottest year in state history. While complaining about the left’s “radical climate agenda” he’s also used “preemption laws” to limit what local governments can do to address the issue such as restricting fertilizer runoff into local waters. He has also rejected $670 million in federal climate funding for energy efficiency and to reduce auto pollution emissions. And yet, he’s still willing to take federal disaster aid, especially given that South Florida has seen massive flooding even before the start of the unusually active 2024 hurricane season.

And then there’s triage: Floridian conservationists have become a leader in a worldwide effort at coral restoration. During last year’s marine heat wave, the Coral Restoration Foundation, the world’s largest group trying to regrow corals, had to do an emergency evacuation of their new plantings from the ocean into onshore tanks and water runways in order to protect them before placing them back in the ocean. With the approach of Hurricane Ian in 2022, another conservation group, the Reef Institute, temporarily relocated endangered pillar corals from the threatened Florida Aquarium in Tampa to its own facilities on the state’s east coast.

These groups are among thousands of organizations and millions of people around the world now involved in ecosystem restoration for coral reefs, mangroves, kelp forests, rainforests, wetlands, soils, rivers, and waterways that will have to become a major endeavor if we’re to have any hope of creating a more livable future.

“We know that coral restoration is required to keep coral reefs from going extinct. There’s no two ways about that now,” Alex Neufeld, the science program manager at the Coral Restoration Foundation, told me after the devastation wrought by 2023’s marine heat wave.

We’ve reached a point where even if we turned off the fossil fuels tomorrow, even if we stopped going to coral reefs, stopped polluting them, stopped touching them, they would not come back on their own. And that’s a really sad statement to make, but it’s the truth. You have to do active restoration now if you want to preserve anything.

Or, in the words of long-dead labor organizer and martyr Joe Hill, “Don’t mourn, organize!” Also, vote in November—because the corals and the fish can’t.