CAPITALISM IS like gravity: it envelops our world so completely that it’s easy to forget about it entirely. The laws of both operate inexorably, and attempts to disregard them can result in serious injury or death. So we become accustomed as a habit of mind to treating them as unchangeable features of the world around us.

No one would stand at the top of the staircase and think they could avoid the reality of descending it. Similarly, in capitalist society, someone headed home after spending the day working in a factory or at a bank doesn’t believe they can simply take with them the value of what they produced—at least not without the risk of losing their job and facing incarceration.

The power of capitalist society to structure the social world—like gravity’s pull on everything around us, including ourselves—is so all-encompassing, in fact, that many people never become aware of it as a force with its own laws.

Other than physicists, few people could state Newton’s law of universal gravitation: that the gravitational force of two bodies of mass is directly proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them.

Likewise, many people go through their daily life without understanding how capitalist society powerfully shapes their world—without asking the question of why what they produced with their hands and brains during a day on the job should belong, by law, to someone else. Or without understanding the connection between capitalism’s economic laws and the rest of the social world, including art, the family, sexuality, the environment and so on.

But capitalism is unlike gravity in at least one crucial respect. It’s a historically specific social structure. Capitalism may be the product of thousands of years of prior human civilizations, but that means it hasn’t existed from the start of human society. It’s a product of human activity and emerged out of a process of historical development. It came after something—and that means it comes before whatever comes next.

The dialectical method is a way of thinking about reality that can be a crucial tool for revealing the passing and transitory nature of a social system that at times—perhaps most of the time—appears to be a fact as real and unmovable as the floor at the bottom of the staircase.

By contrast, dialectics takes as its starting point that the social world is in a constant state of change and flux—and that capitalism, while it powerfully structures human relationships, is itself the product of human activity that emerges out of the material world, including the natural world.

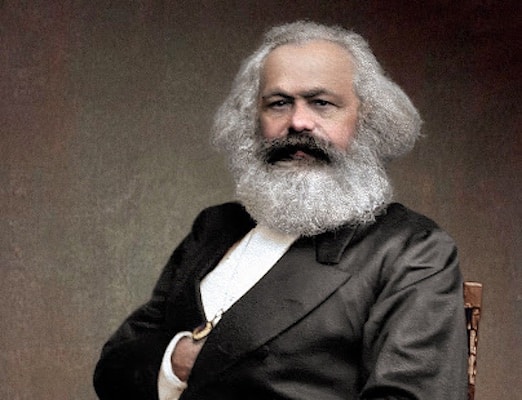

FOR THIS reason alone, it should be obvious why the people who run our society despise the very idea of dialectics. As Karl Marx put it in an afterword to a German edition of the first volume of his masterwork of dialectical analysis Capital:

In its rational form it is a scandal and an abomination to the bourgeoisie and its doctrinaire spokesmen, because it includes in its positive understanding of what exists a simultaneous recognition of its negation, its inevitable destruction; because it regards every historically developed form as being in a fluid state, in motion, and therefore grasps its transient aspect as well; and because it does not let itself be impressed by anything, being in its very essence critical and revolutionary.

Even at those moments in history when society appears stable and impervious to change, the truth is that it is changing—all the time, though often in imperceptibly small ways. These “molecular” changes eventually pile up and give way to sudden ruptures and transformations—which can take the form of upheavals, wars and revolutions. Writing in 1939, the Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky summed up the dialectical method, which was first given systematic expression by the German philosopher Georg Hegel in the early 19th century:

Hegel’s logic is the logic of evolution. Only one must not forget that the concept of “evolution” itself has been completely corrupted and emasculated by university professors and liberal writers to mean peaceful “progress.” Whoever has come to understand that evolution proceeds through the struggle of antagonistic forces; that a slow accumulation of changes at a certain moment explodes the old shell and brings about a catastrophe, revolution; whoever has learned finally to apply the general laws of evolution to thinking itself, he is a dialectician, as distinguished from vulgar evolutionists. Dialectic training of the mind, as necessary to a revolutionary fighter as finger exercises to a pianist, demands approaching all problems as processes and not as motionless categories. Whereas vulgar evolutionists, who limit themselves generally to recognizing evolution in only certain spheres, content themselves in all other questions with the banalities of “common sense.”

The late great biologist Stephen Jay Gould, who drew on the dialectical method in several of his most important contributions to the study of evolution, put it this way:

When presented as guidelines for a philosophy of change, not as dogmatic precepts true by fiat, the three classical laws of dialectics [formulated by Frederick Engels] embody a holistic vision that views change as interaction among components of complete systems, and sees the components themselves…as both products of and inputs to the system. Thus the law of “interpenetrating opposites” records the inextricable interdependence of components; the “transformation of quantity to quality” defends a systems-based view of change that translates incremental inputs into alterations of state; and the “negation of negation” describes the direction given to history because complex systems cannot revert exactly to previous states.

FOR MARXISTS, therefore, the dialectical method consists in going beyond the recognition of this or that instance of inequality and injustice in capitalism. Cataloguing and describing the multitude of different kinds of oppression and injustice in our world is important, but it’s not necessary to be a Marxist or a dialectician to do so.

A dialectical approach to oppression explains how such oppression is part and parcel of a larger social whole, rather than a static and unchanging fact independent of other social factors. A dialectical inquiry into oppression reveals how systems of oppression are connected to the antagonistic and opposed interests of competing social forces—and are both built up and resisted, in a contest between those who try to impose oppression and those who challenge it.

And the dialectical method describes how oppression and the ideas that sustain it interact in turn with the rest of the moving parts of capitalist society as a whole, including not just the economy, but also the media, the family, the criminal justice system and so on.

Yet as this example illustrates, a dialectical approach is not necessarily a Marxist one. Many mainstream social scientists working in the fields of sociology, philosophy, anthropology and so on attempt to analyze the world as a social whole. But most social science doesn’t have any notion of how the parts of the social whole stand in relation to the others—beyond a nondescript notion that “a multiplicity of historical factors” are at work simultaneously. Put another way, everything affects everything.

Karl Marx brought together dialectics and materialism to understand the world as a totality—but as a totality driven by inherent change, conflict and contradictions rooted in the material world, where human activity, including the ideas generated by humans about the world, can also react back on and in turn transform the material underpinnings of society.

TO UNDERSTAND what a profound insight Marx pioneered, it’s useful to begin with Hegel’s conception of the dialectic—in order to show what was distinctive in the way that Marx refined and then deployed dialectics.

“Contradiction is at the root of all movement and life, and it is only in so far as it contains a contradiction that anything moves and has impulse and activity,” Hegel wrote in The Science of Logic, which first appeared in print in 1812. Hegel’s point—that antagonism, conflict and contest are not a secondary aspect of reality, but central to it—represented a dramatic leap forward compared to what had come before in the realm of philosophy.

For centuries stretching back to the ancient Greeks and culminating in the scientific revolution of the Enlightenment era, the development of scientific knowledge about the world had largely consisted in breaking up everything in the world into discrete parts, defining what’s essential to each part, and making a record of these properties.

The aim was to separate the objects under investigation into ever-more specific classifications. One good example is the way of defining biological organisms on the basis of shared characteristics and assigning them to ever more specific categories—domain, kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus and finally species.

The philosophical underpinning of this pursuit of knowledge was grounded in the empirical method, which guided the scientific inquiry into the interactions conceived of as external to these discrete and now well-defined entities. The law of identity was critical to the project: A thing is always equal to or identical with itself. Or stated in algebraic terms: A equals A. One corollary of the idea that A is always identical to A is that A can never equal not-A.

But the law of identity troubled Hegel. When he surveyed modern philosophy, culture and society, he was struck by the contradictions—the tension between the subject and object, freedom and authority, knowledge and faith. Hegel’s main philosophical aim was to interpret these contradictions and tensions as part of a comprehensive, evolving and ultimately rational unity, which he called “the absolute idea” or the Absolute Spirit.

In this sense, Hegel’s method sought to reveal the contradictions and change internal to discrete “species” of philosophical inquiry—and to reveal the processes of transformation that connected them to one another.

It’s important to point out that Hegel didn’t reject outright the usefulness of non-dialectical classifications of the world. As British Marxist John Rees explains in his book about the dialectic The Algebra of Revolution:

Hegel thought that the standard empirical procedure of breaking things down into their constituent parts, classifying them, and recording their properties was a vital part of the dialectic. This is the first stage of the process…It is only through this process of trying to capture things with “static” terms that contradictions emerge which oblige us to define something by its relations with the totality, rather than simply by its inherent properties. To show their transitory nature, Hegel called these stable points in the process of change “moments.” Hegel said that the whole was “mediated” by its parts. So empirical definitions were not irrelevant. But they were an inadequate way of looking at the world and so in need of a dialectical logic which could account for change.

BUT AS innovative, even revolutionary, as Hegel’s dialectical method was, it was also limited by Hegel’s idealism. Idealism means that the ideas of society—the sum total of its concepts and knowledge—drive the process of change in the social world.

Enter Karl Marx and his materialist account of human society. Marx drew on Hegel’s understanding of dialectics in his insistence that society be conceived of as a totality—as a whole made up of interconnected parts that are in constant change and flux. And he agreed with Hegel that the source of this change wasn’t some external force, such as God, but that change is a feature intrinsic to each part of the whole.

But Marx provided a material basis for identifying the source of this internal change. Where Hegel saw ideas as the motor force of history, Marx looked at the forces of production—the way humans collectively produce their means of subsistence and reproduce themselves—as the source of internal change, contradiction and conflict.

In a speech delivered at Marx’s funeral in 1883, Frederick Engels summarized the Marxist version of the dialectic:

Just as Darwin discovered the law of development of organic nature, so Marx discovered the law of development of human history: the simple fact, hitherto concealed by an overgrowth of ideology, that mankind must first of all eat, drink, have shelter and clothing, before it can pursue politics, science, art, religion, etc.; that therefore the production of the immediate material means, and consequently the degree of economic development attained by a given people or during a given epoch, form the foundation upon which the state institutions, the legal conceptions, art, and even the ideas on religion, of the people concerned have been evolved, and in the light of which they must, therefore, be explained, instead of vice versa, as had hitherto been the case.

Hegel’s idealism led him to believe that the social conflicts and economic crises of his times could be resolved through the bourgeois state and humanity’s pursuit of the Absolute Spirit. For Hegel, the modern representative state could guarantee the individual rights necessary for general freedom and rationality, which would make it possible for humanity to eventually comprehend the Absolute Spirit.

For Marx, the contradictions were based in the material world—at root, a conflict between the main contending classes of capitalist society, the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. Therefore, they could only be resolved through social transformation, a revolution that would abolish the antagonistic and the mutually interdependent relation of capitalist and worker.

Engels described Marx’s materialist dialectic as standing Hegel’s dialectic on its head—or rather lifting it off its head and setting it on its feet. According to Marx, his materialist approach rescued Hegel’s dialectic from idealism in order to discover “the rational kernel within the mystical shell.”

OF COURSE, the insights pioneered by both Hegel and Marx can also be explained in terms of a historical materialist analysis of their own time and place in history.

Hegel lived from 1770 to 1831, and his greatest works were written in the immediate aftermath of the French Revolution, the period of social upheaval that spanned the years 1789 to 1799, when France’s feudal monarchy was swept away and replaced, albeit temporarily, with a republic. The rule of kings by divine right was tossed into the dustbin of history and replaced it with “liberté, egalité and fraternité”—the principles of individual rights.

It’s easy to see why Hegel’s philosophical insights stressed process over classification, conflict and contradiction over stasis and stagnation. At the same time, his distance from events in France and his sweeping knowledge of history, philosophy, aesthetics and logic allowed him to step back from the crush of living through the historically path-breaking events, and to place them in a longer historical sweep.

Karl Marx’s life spanned the years 1818 to 1883. He was witness to the first working class movement in world history: the Chartists of the 1840s and ’50s. While Hegel lived in Germany at some distance from the political earthquake that shook France in the late 18th century, Marx was born in Prussia, but also lived in Paris and London. He lived through the revolutions of 1848 that spread across Europe, including Prussia. But he was also a witness to the factories and other products of the Industrial Revolution, allowing him to absorb the dramatic and massive economic forces being called into existence by the growth of capitalist industry.

In Marx’s time, capitalism represented a leap forward from the stagnation of feudal society, with its train of religious authority, superstition and tradition. Compared to the feudal economy, capitalism was highly dynamic, innovative and efficient.

But Marx also showed how capitalist relations of production would eventually come to frustrate the further development of human society. So even as capitalism conjured tremendous economic growth, efficiency and technological innovation, it also resulted in an ever-greater concentration and centralization of the means of production in private hands, the immiseration of the working class, and more destructive and convulsive economic crises.

DIALECTICAL THEORIES about the social world aren’t necessarily materialist, as mentioned above. Many social scientists conceive of the world as a totality made up of interacting parts undergoing various transformations, but without giving any special explanatory role to the material world. Instead, they opt for the view that everything affects everything.

As George Novack explained in an essay about Trotsky and dialectics in his book Polemics in Marxist Philosophy, this was once Trotsky’s attitude as well:

Trotsky tells in [his autobiography] My Life how he at first resisted the unified outlook of historical materialism. He adopted in its stead the theory of “the multiplicity of historical factors,” which even today is the most widely accepted theory in social science…His reading of two essays by the Italian Hegelian-Marxist Antonio Labriola convinced him of the correctness of the views of the historical materialists. They conceived of the various aspects of social activity as an integrated whole, historically evolving in accord with the development of the productive forces and interacting with one another in a living process where the material conditions of life were ultimately decisive. The eclectics of the liberal school, on the other hand, split the diverse aspects of social life into many independent factors, endowed these with superhistorical character, and then “superstitiously interpreted their own activity as the result of the interactions of these independent forces.”

This eclectic view of how the social world changes is the product of a dialectical method, but without Marx’s materialist underpinnings.

On the other extreme, there are any number of theories about the social world that are materialist, but reject the dialectical method. Such approaches lead to what Marxists call a mechanical materialism, which is at best one-sided, suggesting that human beings and their behavior are a mostly reflexive reaction to their surroundings. For example, sociobiology and evolutionary psychology seek out biological explanations for various social problems and inequalities.

In the fields of sociology and economics, a number of theorists insist on the approach of methodological individualism, which requires that all social phenomena, including structure and change, be explained in terms of individual properties, goals, beliefs and actions. Methodological individualism is the underlying assumption of social theories that rely on game theory to explain how the rational choices of individual actors can explain all the key elements of societies and social change.

These mechanical materialist theories end up stressing in a one-sided way how human biology (sociobiology) or the human drive to maximize material gain and minimize loss or risk (methodological individualism) are the only way to generate valid insights about the social world.

By contrast, the dialectical method—with its stress on the internal contradictions and interpenetrating linkages of the material and the social world—rescues historical materialism from a vulgar economic determinism, which tends to understate the role of history and politics in human societies, instead seeing humans as reacting reflexively to their surroundings, as “naked apes” or inexorably guided by the drive for material gain.

IN RESPONDING to both critics and “defenders” of Marx’s materialist method who misunderstood it, Engels wrote in an 1890 letter to a friend:

According to the materialist conception of history, the ultimately determining element in history is the production and reproduction of real life. Other than this neither Marx nor I have ever asserted. Hence if somebody twists this into saying that the economic element is the only determining one, he transforms that proposition into a meaningless, abstract, senseless phrase. The economic situation is the basis, but the various elements of the superstructure—political forms of the class struggle and its results, to wit: constitutions established by the victorious class after a successful battle, etc., juridical forms, and even the reflexes of all these actual struggles in the brains of the participants, political, juristic, philosophical theories, religious views and their further development into systems of dogmas—also exercise their influence upon the course of the historical struggles and in many cases preponderate in determining their form.

This same point was stated the other way around by Marx earlier, in his The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte:

Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past. The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living.

The materialist component of the Marxist method grounds explanation of the social world in the economic underpinnings of society—in the fact that we “must first of all eat, drink, have shelter and clothing, before [we] can pursue politics, science, art, religion.” The dialectical component stresses that the social world itself is the product of multiple interpenetrating parts that are undergoing constant change, and that human activity itself, including our attempts to comprehend the social world, also plays a role in the process of change. This is true even when society appears at its most stable and unchanging.

This is crucial for understanding how Marxism provides both an explanation of how society works and an understanding of the ways that, under certain circumstances, conscious human activity can transform that society. As Trotsky put it in his autobiography:

Marxism considers itself the conscious expression of the unconscious historical process. But the “unconscious” process, in the historico-philosophical sense of the term, not in the psychological, coincides with its conscious expression only at its highest point, when the masses, by sheer elemental pressure, break through the social routine and give victorious expression to the deepest needs of historical development. And at such moments the highest theoretical consciousness of the epoch merges with the immediate action of those oppressed masses who are farthest away from theory. The creative union of the conscious with the unconscious is what one usually calls “inspiration.” Revolution is the inspired frenzy of history.