They built the world as we know it, all the systems you traverse.

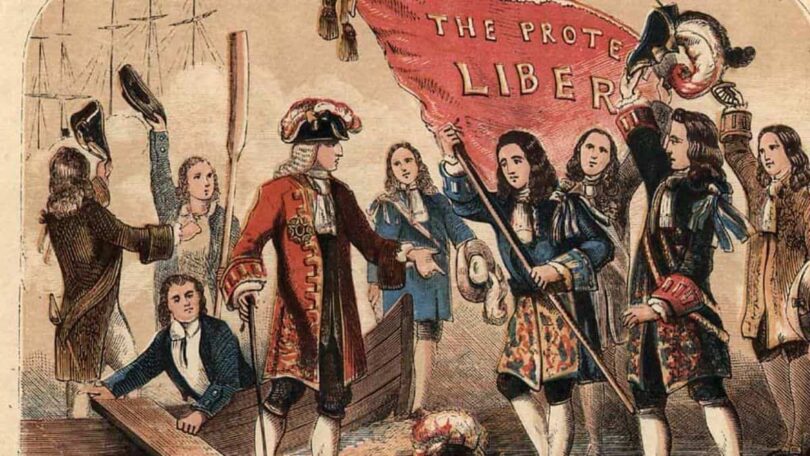

Thus sang The Fall’s Mark E. Smith on the Manchester band’s 1988 record, I Am Kurious Oranj, written for a ballet based on the 300th anniversary of William of Orange’s ascension to the English throne. While some of the credits Smith bestowed on King William III warrant closer inspection—having “paved the way for the atom bomb” and “inventing birth control,” for instance—what the revolution of 1688 did pave the way for was the radical transformation of Britain’s socioeconomic order in favor of capitalist accumulation. With William’s rise to power, the country’s emergent bourgeoisie secured the political hegemony needed to bend the apparatus of the state to their collective will, smashing up the existent feudal and familial alliances that characterized the pre-capitalist economy, enabling the mass appropriation of common land by industrial agriculture, and forcing the newly dispossessed peasantry to take up the mantle of wage labor. Often styled the “Glorious” or “Bloodless” Revolution, 1688 enshrined the conditions by which state power became an instrument for subordinating land and labor to the demands of capital.

Barriers to Capital Before 1688

The wealth of the English bourgeoisie—loosely made up of merchants, manufacturers, financiers, and landed capitalists—accumulated rapidly in the century leading up to revolution, as the country’s manufacturing and commercial enterprises experienced rapid development. Such prosperity was assisted in no small part by England’s lucrative stake in the Atlantic Slave Trade: between 1676 and 1726 the number of enslaved people transported by British traders from Africa to North America increased from 243,300 to 490,500. Such was the expansion of Britain’s involvement in global trade that by 1688 its commercial and industrial enterprises were generating over a third of the national income. But for the profits accruing to the bourgeoisie to continue unchecked, it was vital that their economic power translate into the political influence capable of uprooting the legal barriers to monopolization. These barriers consisted largely of property rights preventing the commercialization of common land and the transferring of funds from the countryside to the city. Historian Geoffrey Hodgson explains that “at the beginning of the eighteenth century about one quarter of arable land in England was held in commons, where villagers shared rights to the use of pastures, water sources or woods. This common land could not be sold or mortgaged.” Such restrictions posed an intolerable legal obstacle to the appropriation of arable land for large-scale industrial farming—an obstacle that the architects of the 1688 Revolution were intent on shattering from behind a royal mask.

The Destruction of Property Rights

The Dutch-led invasion brought with it an influx of Dutch financiers and businessmen who, with their relatively sophisticated knowledge of public and private finance, helped remodel England’s financial and administrative institutions to facilitate the bourgeoisie’s political hegemony. This came about in a series of Acts—beginning with the 1689 Declaration of Rights—which succeeded in eroding the legal protections concerning the sale of common land, entails, and “strict settlements.” Such acts also succeeded in hobbling the prestige of the nobility and landed gentry, whose vested interest in the feudal nature of property rights was sorely affected by the government selling off land for industrial farming. But as the state became increasingly dependent on the bourgeois class to fund the country’s various European wars (funding which increased from £2,000,000 per year before 1688 to £6,000,000 between 1689 and 1702), so it became increasingly receptive to their demands for deregulation and the privatization of common land.

Accumulation by Dispossession

The impact of this institutional shakeup on the majority of the population offers an object lesson in the art of what David Harvey refers to as

“accumulation by dispossession.” The rural peasantry was swept of the newly privatized land to make way for sheep farming and large landed estates. The traditional agrarian communities were broken up and the mass of displaced people, with little option but to sell their labor power in the new urban industries, were forced into the ranks of the proletariat. As Karl Marx observed, this forcible alienation of the rural populace from their land produced “a degraded and almost servile condition of the mass of the people, their transformation into mercenaries, and the transformation of their means of labour into capital.”

The Highland Clearances provide a stark example of the kind of systematic theft of communal property, and the attendant forced evictions, that were made possible under the reorganized state. The Clearances involved the forcible transformation of the property of the Highland clans—common land on which the rural communities of northern Scotland made their living—into the private property of English nobles who coveted the land for pasturage. With the aid of the English military, the families who for centuries had lived in this region were systematically expelled and exterminated to make room for sheep and cattle farms; their villages razed and homes burned. Sporadic resistance to eviction was met with brutal reprisals, terrorism, and executions. Most of the newly appropriated land was subdivided into large sheep farms, mostly occupied by English farm-laborers paying rent to an absentee lord. In the case of the one-million-acre estate she seized, the Countess of Sutherland was “generous” enough to sell 6,000 acres of barren rock back to the 15,000 men, women, and children evicted from their homes.

Creating the Laboring Poor

This type of terroristic landgrab, which continued well into the nineteenth century, succeeded in pushing swathes of people into abject poverty just as they were separated from their homes and their means of sustaining themselves. The state’s response to this newly immiserated class is one that should be familiar to us today: it dehumanized them, branded them thieves and vagabonds, punished them with systemic oppression, and threw them in jail. Such punitive measures were aimed at socializing the dispossessed into accepting the disciplinary apparatus of capital and their new situation as the laboring poor. The overt violence unleashed during the initial stages of proletarization was followed by the softer powers of the state to preserve this new economic hegemony: education, policing, and laws inhibiting collective organization. As Marx reflected on the disenfranchisement of the rural populace, “Thus were the agricultural folk first forcibly expropriated from the soil, driven from their homes, turned into vagabonds, and then whipped, branded, and tortured by grotesquely terroristic laws into accepting the discipline necessary for wage-labour.”

This is not to say that the social order displaced by the revolution’s expansion of capitalist accumulation was some halcyon age, the “Merrie England” mourned in Thomas Gray’s Elegy, and of course many went happily from the countryside to the new industrial centers in hopes of a better standard of living and improved working conditions. Yet, the institutional reforms dreamed up by the architects of William’s rise to power brought new means of exploitation and expropriation, by which the assets and rights of the common people were eroded and a massive concentration of wealth at the top end of the scale enabled.