The outcome of the 2024 British General Election was never in doubt. A Conservative Party lurching from crisis to crisis, from leader to leader, was staring at a heavy defeat. Opinion polls up to 24 hours before the election consistently gave Keir Starmer’s Labour a lead of 15-20%.

Starmer dreamt of winning a landslide victory over the Tories but equally important to him were two other dreams: the marginalisation of left-wing opponents within the Party, and the total vanquishing and humiliation of the left-wing former leader of the Party, Jeremy Corbyn. Corbyn was standing this time as an Independent candidate in his innerLondon, Islington North Constituency that he had represented for the Labour Party since 1983. Independents, however well-known, rarely succeed in breaking through Britain’s archaic “first past the post” election system dominated by big party machines.

Starmer won his landslide: 64% of the seats in Parliament but, astonishingly, on less than 34% of the vote share (far fewer than the 40% vote share Corbyn achieved in his first attempt to win a General Election in 2017). Despite the Tories’ disastrous campaign, their vote held up at 24%. The surprise in the pack was the far-right populist Reform Party, led by Nigel Farage, which collected more than 14% of the national vote share and won five seats in Parliament, taking votes from both former Tory and Labour supporters.

In absolute numbers, combined votes for the Tories and Reform outstripped Labour. In Starmer’s own seat, his personal vote went down by more than 18,000. A large chunk of those votes went instead to an excellent Independent left-wing candidate, Andrew Feinstein, a South African born anti-Zionist Jew who at one time served as an ANC MP under Nelson Mandela. Many of Starmer’s closest right-wing allies saw their personal vote fall massively in their constituencies. Jonathan Ashworth, one such ally who would certainly have held a Cabinet post, suffered a shock defeat to an independent. And Starmer’s new Health Minister, Wes Streeting, defending a majority of more than 5,200, saw that shrink to barely 500. This was due to an Independent challenge from 23-year-old Leanne Mohammed, a British-Palestinian who focused significantly on Labour’s shortcomings in its stance on the Gaza War.

Starmer’s dream of finally destroying Corbyn turned to a nightmare. The ever-energetic veteran left-winger won a comfortable majority of 7,500 over his Labour opponent, Praful Nargund, a young multi-millionaire who has made his fortune as director of a set of private health and venture capitalist companies, and is an unimpressive local Labour councillor in the neighbouring constituency of Islington South.

A week before the election was announced, the Labour hierarchy had started a nomination process in Islington North from which Corbyn was barred. Nargund was one of a few names put forward. Once the election was declared, that internal process was abruptly ended and Nargund was simply imposed on the local party, with local members having no say.

Newspapers claimed that despite Corbyn’s campaign as an independent starting positively and energetically, opinion polls suggested that Nargund was 5% ahead in that seat as the election day approached. The media described exit polls on the day as “too close to call”. They and Starmer were equally in denial about Corbyn’s continued appeal and the nature and effectiveness of what he had described as a “people-powered campaign”.

I rejoined the Labour Party in 2015, when Corbyn stood for the Labour leadership. I resigned in 2022 in protest of their attacks on democracy, their anti-left witch-hunting and the utter dishonesty of their supposed campaign against antisemitism which was anything but, having resulted in many left-wing Jews being pushed out of the Party.

I was excited, and not at all surprised, when Corbyn declared that he was standing as an Independent. And having been heavily involved in that campaign at different levels, I can identify some of the key factors that made it successful, and how that might inspire other successful campaigning from the Left.

At its heart was:

- accessibility – valuing people and enabling them to contribute their skills and energy in a way that was possible for them.

- egalitarianism – an absence of unnecessary hierarchies, and a strong collective spirit built on working together, and online channels of communication between activists that enabled a free flow of ideas, reflections and suggestions.

- principle – a campaign that was unafraid to express its radical political messages in straightforward language, as they related to both local and global issues.

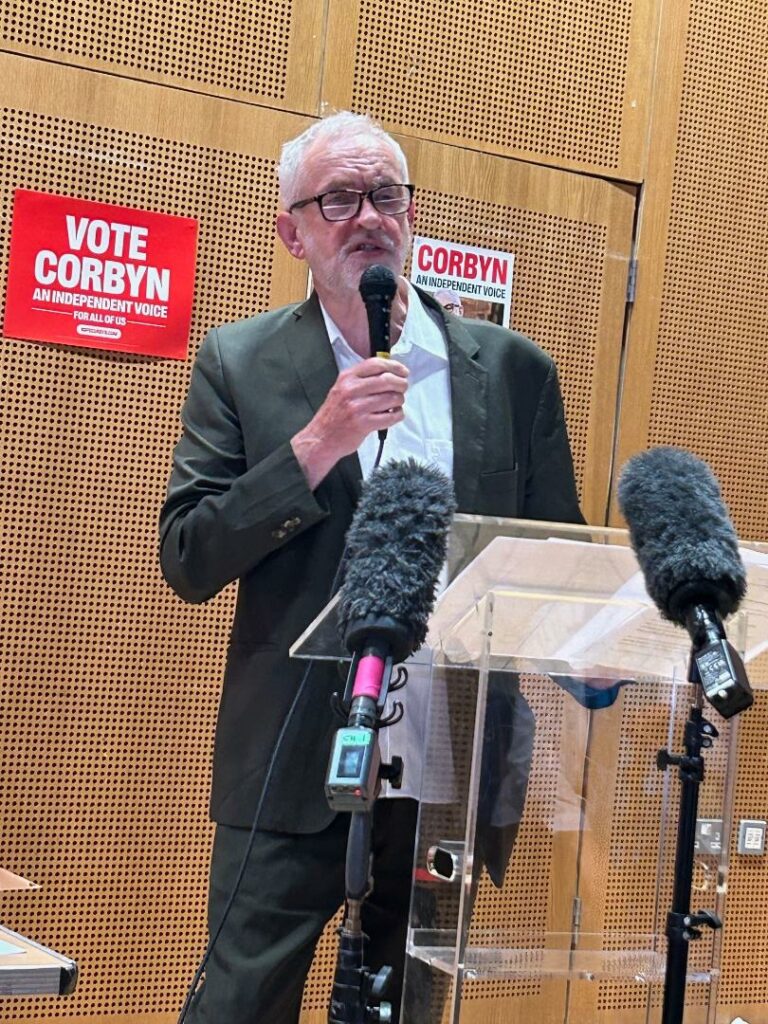

These values were modelled by Corbyn himself. As a politician who is completely unafraid to engage directly with the public, he is an increasingly rare species in Britain. He constantly seeks to talk with people, listen to them, and work alongside them. He urged us to keep to positive messages, not to descend into the gutter with opponents when they abused us.

We knew that, should he stand as an independent, people would travel a long way to support him. I took part in one of several canvassing sessions on the first weekend after the election was called. Around 25 of us formed a circle at our meeting point and people briefly introduced themselves. The two people running the canvass were in tears as they explained they had resigned from the Labour Party that very morning after many, many years, in order to work to elect Corbyn again.

Several people in the circle were local but then the areas named became more distant, until one man, a train driver, said he had travelled from Hull (290 kilometres away) that morning to join the campaign! That seemed astonishing, but later in the campaign we encountered people from all over England as well as Scotland, Wales and Ireland. In the campaign’s final days, one of the most hostile anti-Corbyn journalists claimed that Corbyn campaigners were being bussed-in with expenses paid to flood the constituency. This was ridiculed by many on social media who described taking their own decisions to travel hundreds of kilometres at their own expense, to campaign for a politician they loved and believed in.

A hub was created close to the offices of the Peace & Justice project that Corbyn founded in 2021. That hub operated almost round the clock. Each time I visited I could feel the positive buzz within–people of all ages, ethnicities and backgrounds, phone-banking, stuffing envelopes, organising canvassing teams, inputting canvass data, dealing with press enquiries and social media, all while consuming tea, donated biscuits and small treats in abundance.

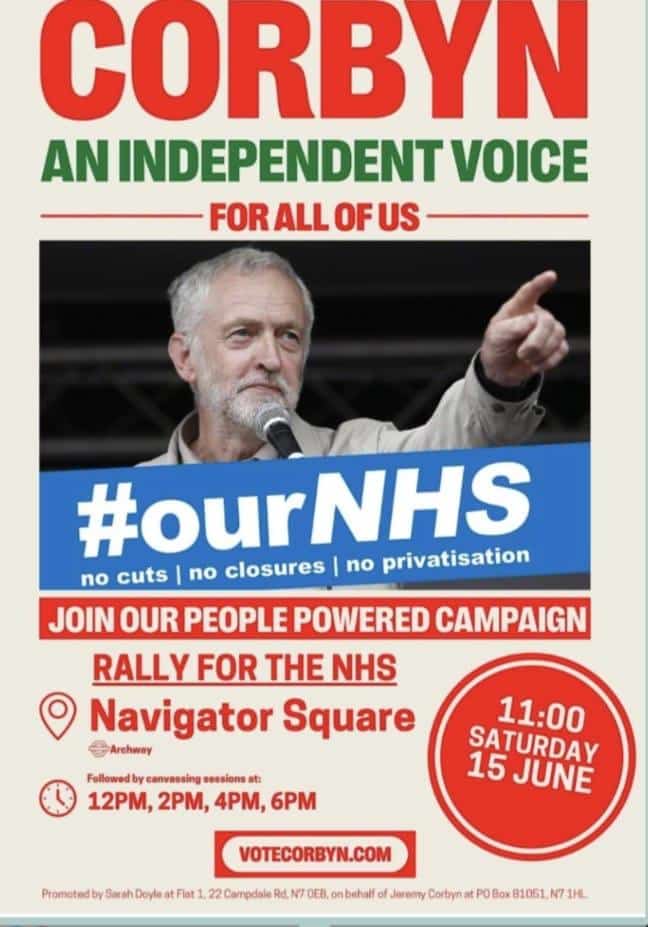

Much of the operation followed a traditional pattern–leafleting voters, returning to hold a conversation with them, inputting data captured, chasing up definite and undecided voters close to election day, and of course on the day itself. But, especially on weekends, canvassing sessions were held immediately after a short rally with guest speakers, including Corbyn himself, focusing on key issues such as housing, health, poverty and the environment. These swiftly arranged local rallies often attracted hundreds, and a good proportion stayed to join canvassing teams.

Corbyn was in the constituency every day, but combined that with his vital campaign work for Palestine in which he had been prominent for several months, as well as attending public meetings for the local candidates to face questions on issues such as the environment, housing and health. Those attending these meetings were unimpressed to see two empty chairs – both Labour and the Tories instructed their candidates not to attend these events, and Corbyn’s labour opponent made the feeblest of excuses.

Responses on the doorstep, to be honest, were mixed. Enthusiastic constituents would describe how Corbyn had helped them solve difficult problems with great determination; but we met others so alienated by politics in 2024 Britain, they were refusing to vote at all. And in a country that in fairly recent times had witnessed the establishment’s sustained character assassination of Corbyn, in which the media, who repeated false accusations trying to label Britain’s most prominent anti-racist parliamentarian an antisemite, we met some families taken in by these lies. Nevertheless, canvass teams were reporting that Corbyn had a lot of support especially on the bigger housing estates.

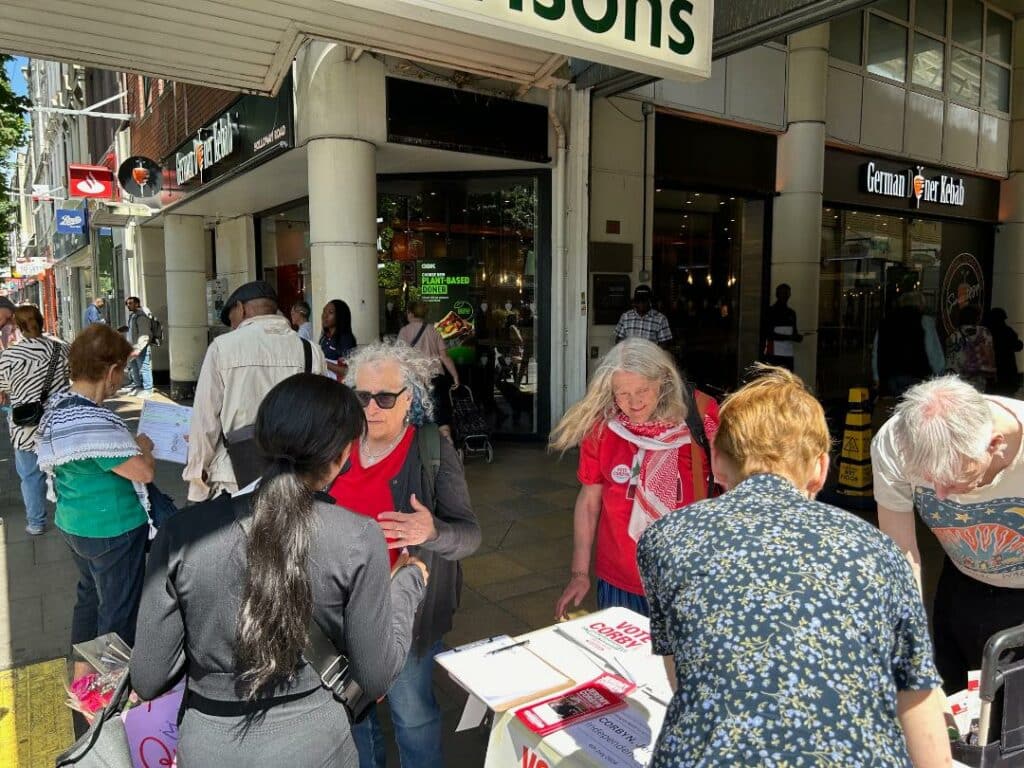

Three weeks into the campaign, a new element was added: “dynamic canvassing”. This took place outside tube stations and supermarkets, where lots of people passed by who you could try to engage in a conversation about the election. They would tell you about how they met Corbyn in a particular campaign or through being involved with a community group, and why they valued him so much. When Corbyn himself appeared on “dynamic canvassing” forays, he would soon be surrounded by people asking him questions or taking selfies with him!

Outside supermarkets we were also confronted with sometimes aggressive behaviour from those who had had their minds poisoned by anti-Corbyn media propaganda in recent years, but if you could get into a conversation it was possible to challenge their beliefs. In one instance a heavily built angry young person was shouting at me that he couldn’t vote for Corbyn because Corbyn was “an antisemite”. I responded, “well I’m Jewish and I’m supporting him; lets chat about this.” He continued to pour out accusations littered with “terrorist”, “Hamas” and so on, but I stayed calm and gradually drew him into a conversation, and pointed to other people leafleting for Corbyn nearby. I suggested we could ask them to join the conversation, “because she’s Jewish… and that one, she’s Jewish too…” I told him some truths about Corbyn’s support for Jewish people through his anti-fascist work. Then I told him about an old Jewish cemetery that, in the 1990s, the local council was allowing to be sold off to developers to build on the land. Corbyn worked with Jewish groups to save the cemetery. I added a further detail implicating the then leader of the council, Margaret Hodge, prominent in later years for accusing Corbyn of “antisemitism”. Our conversation ended with this constituent calm but somewhat confused. And of course other passers-by were listening in.

Alongside daily canvassing of households and “dynamic canvassing”, the campaign organised a team doing specialist work among the different communities, especially the large Muslim communities locally. Over the decades, Corbyn has built up very positive relations with religious/ethnic minorities, community campaigns and local trade unionists. This “community engagement team” worked through the campaign period to strengthen support from those groups. Lots of work was done with local mosques. Trade unionists who knew Corbyn from their picket lines came from far and wide to canvass for him.

In the last 10 days of the campaign a letter was made public, especially on social media, with more than 70 signatures of local Labour Party officers who had resigned from the Party in order to campaign openly for Corbyn. In the final week of the campaign, embarrassing material about the Labour candidate’s involvement with private health was getting an airing. He did not refute these himself, though his supporters described it as a “smear campaign”. It wasn’t. It simply contrasted direct evidence of his vocal support for further privatisation in the health service with Corbyn’s decades of support for the National Health Service.

Social media was flooded with photos from the canvassing campaign. Nargund’s campaign photos featured very few recognisable faces from the local Labour Party, but he did have several featuring organised support from the “Jewish labour Movement“ (JLM)–an explicitly pro-Zionist group affiliated to Labour but firmly on its right wing. It had played a key role campaigning within Labour against Corbyn when he was leader and worked overtime to get members critical of Israel/Zionism disciplined and expelled from the party. JLM openly boycotted the 2019 election, save for a few seats. Effectively they were seeking a Labour election defeat to the Tories, the party of the Hostile Environment towards migrants and refugees. Well known and deeply unpopular right wing members of the Labour Party, such as Peter Mandelson, Margaret Hodge and Tom Watson publicly canvassed for Nargund. This may not have helped him!

In the early hours of 5th July, news came from the count that Corbyn’s camp were becoming quietly more confident while Nargund’s camp were more circumspect and preparing themselves for a disappointment. The announcement of the result, followed by Corbyn’s defiant but respectful acceptance speech, was a joy to watch. When we heard over the coming hours that a number of other left-wing Independents had succeeded, that joy was doubled. This election has done much more than simply end Tory rule. It has shown that there are ways to successfully challenge the machine politics of right-wing labour, and we intend to build on that.