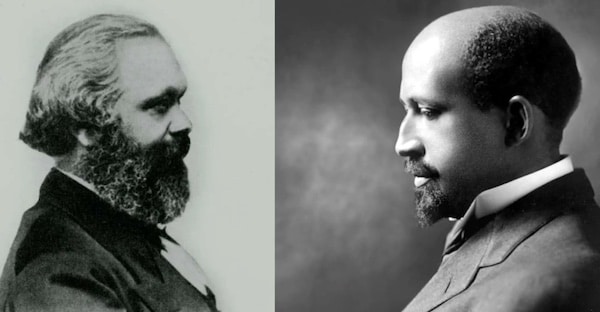

WITHOUT doubt the greatest figure in the science of modern industry is Karl Marx. He has been a center of violent controversy for three-quarters of a century, and for that reason there are some people who are so afraid of his doctrines that they dare not study the man and his work. This attitude is impossible, and particularly today when the world is so largely turning toward the Marxian philosophy, it is necessary to understand the man and his thought. This little article seeks merely to bring before American Negroes the fact that Karl Marx knew and sympathized with their problem.

Heinrich Karl Marx was a German Jew, born in 1818 and died in 1883. His adult life, therefore, reached from the panic of 1837 through the administration of President Hayes. The thing about him which must be emphasized now was his encyclopedic knowledge. No modern student of industry probably ever equalled his almost unlimited reading and study.

He knew something about American Negroes from his German comrades who migrated to the United States; but these emigrants were of little help so far as his final conclusions were concerned. Kriege, a German radical, who came to the United States, said frankly in 1846, that “We feel constrained to oppose abolition with all our might.” Weitling, a Communist, paid scant attention to the slavery question. The German Labor Convention at Philadelphia in 1850 was dumb on slavery. Even Weydemeyer, Marx’s personal friend, said nothing about slavery in his Workingmen’s League, which was founded in 1853, although the next year he opposed the Kansas-Nebraska Bill. When the League was re-organized in 1857, it still said nothing about slavery, and a powerful branch of the League which seceded in 1857 advocated widespread serfdom of blacks and Chinese. Then came the war and Marx began to give the situation attention.

“The present struggle between the South and the North,” he wrote in 1861, “is…nothing but a struggle between two social systems, the system of slavery and the system of free labor. Because the two systems can no longer live peaceably side by side on the North American continent, the struggle has broken out.”

He was well acquainted with those splendid leaders of the English workers who kept England from recognizing the South and perhaps entering the Civil War, who employed Frederick Douglass to arouse anti-slavery sentiment, and who organized those monster mass meetings in London and Manchester late in 1862 and early in 1863. It is possible that Marx had some hand in framing the addresses sent to President Lincoln in which they congratulated the Republic and found nothing to condemn except “The Slavery and degradation of men guilty only of a colored skin or African parentage.” The Manchester address congratulated the President on liberating the slaves in the District of Columbia, putting down the slave trade, and recognizing the Republics of Haiti and Liberia, and concluded that “You cannot now stop short of a complete uprooting of slavery.”

It was after this, in September, 1864, that the International Workingmen’s Association was formed in which Marx was a leading spirit, and his was the pen that wrote the address to Abraham Lincoln in November, 1864. “To Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States of America.

“Sir: We congratulate the American people upon your reelection by a large majority. If resistance to the Slave Power was the watchword of your first election, the triumphal war-cry of your re-election is Death to Slavery.

“From the commencement of the titanic American strife the workingmen of Europe felt distinctively that the Star Spangled Banner carried the destiny of their class. The contest for the territories which opened the dire epogée, was it not to decide whether the virgin soil of immense tracts should be wedded to the labor of the immigrant or be prostituted by the tramp of the slave-driver?

“When an oligarchy of 300,000 slave-holders dared to inscribe for the first time in the annals of the world ‘Slavery’ on the banner of armed revolt, when on the very spots where hardly a century ago the idea of one great Democratic Republic had first sprung up, whence the first declaration of the Rights of Man was issued, and the first impulse given to the European Revolution of the eighteenth century, when on those very spots counter-revolution, with systematic thoroughness, gloried in rescinding ‘the ideas entertained at the time of the formation of the old constitution’ and maintained ‘slavery to be a beneficial institution.’ indeed, the only solution of the great problem of the ‘relation of capital to labor,’ and cynically proclaimed property in man ‘the cornerstone of the new edifice, then the working classes of Europe understood at once, even before the fanatic partisanship of the upper classes, for the Confederate gentry had given its dismal warning, that the slaveholders’ rebellion was to sound the tocsin for a general holy war of property against labor, and that for the men of labor, with their hopes for the future, even their past conquests were at stake in that tremendous conflict on the other side of the Atlantic. Everywhere they bore therefore patiently the hardships imposed upon them by the cotton crisis, opposed enthusiastically the pro-slavery intervention-importunities of their betters–and from most parts of Europe contributed their quota of blood to the good of the cause.

“While the workingmen, the true political power of the North, allowed slavery to defile their own republic, while before the Negro, mastered and sold without his concurrence, they boasted it the highest prerogative of the white-skinned laborer to sell himself and choose his own master, they were unable to attain the true freedom of labor, or to support their European brethren in their struggle for emancipation; but this barrier to progress has been swept off by the red sea of civil war.

“The workingmen of Europe felt sure that, as the American War of Independence initiated a new era of ascendency for the middle class, so the American Anti-slavery War will do for the working classes. They consider it an earnest sign of the epoch to come that it fell to the lot of Abraham Lincoln, the single-minded son of the working class, to lead his country through the matchless struggle for the rescue of the enchained race and the reconstruction of a social world.”

To this the American Ambassador to London replied sympathetically. After Lincoln’s assassination, Marx again drafted a letter, May 13, 1865, in behalf of the International Association.

“The demon of the ‘peculiar institution,’ for whose preservation the South rose in arms, did not permit its devotees to suffer honorable defeat on the open battlefield. What had been conceived in treason, must necessarily end in infamy. As Philip II’s war in behalf of the Inquisition produced a Gérard, so Jefferson Davis’s rebellion a Booth.

“After a gigantic Civil War which, if we consider its colossal extension and its vast scene of action, seems in comparison with the Hundred Years’ War and the Thirty Years’ War and the Twenty-three Years’ War of the Old World scarcely to have lasted ninety days, the task, Sir, devolves upon you to uproot by law what the sword has felled, and to preside over the more difficult work of political reconstruction and social regeneration. The profound consciousness of your great mission will preserve you from all weakness in the execution of your stern duties. You will never forget that the American people at the inauguration of the new era of the emancipation of labor placed the burden of leadership on the shoulders of two men of labor-Abraham Lincoln the one, and the other Andrew Johnson.”

After the war had closed, in September, 1865, still another letter went to the people of the United States from the same source.

“Again we felicitate you upon the removal of the cause of these years of affliction-upon the abolition of slavery. This stain upon your otherwise so shining escutcheon is forever wiped out. Never again shall the hammer of the auctioneer announce in your market-places sales of human flesh and blood and make mankind shudder at the cruel barbarism.

“Your noblest blood was shed in washing away these stains, and desolation has spread its black shroud over your country in penance for the past.

“Today you are free, purified through your sufferings. A brighter future is dawning upon your republic, proclaiming to the old world that a government of the people and by the people is a government for the people and not for a privileged minority.

“We had the honor to express to you our sympathy in your affliction, to send you a word of encouragement in your struggles, and to congratulate you upon your success. Permit us to add a word of counsel for the future.

“Injustice against a fraction of your people having been followed by such dire consequences, put an end to it. Declare your fellow citizens from this day forth free and equal, without any reserve. If you refuse them citizens’ rights while you exact from them citizens’ duties, you will sooner or later face a new struggle which will once more drench your country in blood.

“The eyes of Europe and of the whole world are on your attempts at reconstruction, and foes are ever ready to sound the death knell of republican institutions as soon as they see their opportunity.

“We therefore admonish you, as brothers in a common cause, to sunder all the chains of freedom, and your own victory will be complete.”

In June of that year, a few months after Johnson had become President, Marx, writing to Engels, senses the beginnings of reaction:

“I naturally see what is repulsive in the form of the Yankee movement, but I find the reason for it in the nature of a bourgeois democracy…where swindle has been on the sovereign throne for so long. Nevertheless, the events are world-upheaving…”

Naturally, Marx stood with the Abolitionist democracy, led by Sumner and Stevens.

“Mr. Wade declared in public meetings that after the abolition of slavery, a radical change in the relation of capital and of property in land is next upon the order of the day.”

He was suspicious of Johnson and wrote Engels in 1865:

“Johnson’s policy disturbs me. Ridiculous affectation of severity against individual persons; up to now highly vacillating and weak in the thing itself. The reaction has already begun in America and will soon be strengthened if this spinelessness is not put an end to.”

And finally, in 1877, after the Negroes had been betrayed by the Northern industrial oligarchy, he wrote:

“The policy of the new president (Hayes) will make the Negroes, and the great exploitation of land in favor of the railways, mining companies, etc. will make the already dissatisfied farmers, into allies of the working class.”

It was a great loss to American Negroes that the great mind of Marx and his extraordinary insight into industrial conditions could not have been brought to bear at first hand upon the history of the American Negro between 1876 and the World War. Whatever he said and did concerning the uplift of the working class must, therefore, be modified so far as Negroes are concerned by the fact that he had not studied at first hand their peculiar race problem here in America. Nevertheless, he,did know the plight of the working class in England, France and Germany, and American Negroes must understand what his panacea was for those folk if they would see their way clearly in the future.

The Crisis A Record of the Darker Races was founded by W. E. B. Du Bois in 1910 as the magazine of the newly formed National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. By the end of the decade circulation had reached 100,000. The Crisis’s hosted writers such as William Stanley Braithwaite, Charles Chesnutt, Countee Cullen, Alice Dunbar-Nelson, Angelina W. Grimke, Langston Hughes, Georgia Douglas Johnson, James Weldon Johnson, Alain Locke, Arthur Schomburg, Jean Toomer, and Walter White.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/sim_crisis_1933-03_40_3/sim_crisis_1933-03_40_3.pdf