Attacks on the Venezuelan electoral system have reached the terrain of cyberwarfare, according to the complaints made by President Nicolás Maduro, the authorities of the National Electoral Council (CNE), and the Attorney General’s Office (MP).

The president of the CNE, Elvis Amoroso, issued a second electoral bulletin on August 2 at noon, where he also reported that there are still signs of massive computer attacks from different parts of the world against the CNE and the Venezuelan state-owned telecommunications companies, which has delayed the transmission of the voting minutes and the announcement of electoral results.

These cyberattacks have been accompanied by the burning of CNE offices in various states and centers for the transmission and reception of computations, causing damage to the electoral infrastructure.

Investigations are ongoing and will be broadened after President Maduro introduced an electoral contentions appeal before the Supreme Court of Justice (TSJ).

However, with the information available up to now, it is possible to tie up loose ends regarding the depth and dimension of this aspect of the hybrid war against Venezuela in the context of a new regime change operation.

Epicenter of cyberattacks

According to the graphs and data published by computer expert Kenny Ossa on July 29, Venezuela was one of the countries that suffered the highest number of cyberattacks in the world.

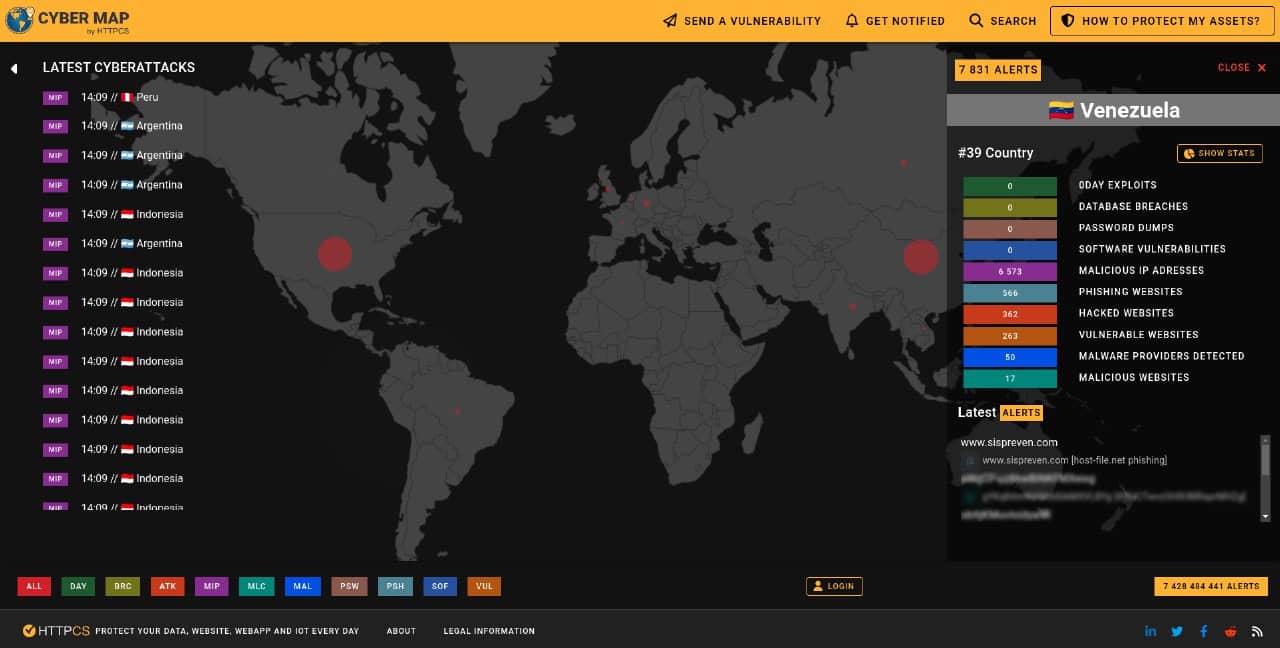

The map of Ziwit HTTPCS shows that on the election and post-election days, Venezuela was the 39th most “cyberattacked” country in the world.

On July 29 at around 7:55 p.m., the real-time Kaspersky map found Venezuela in 46th place among the countries that have suffered the highest number of cyberattacks in the world, out of 200.

Ossa called attention to “the evident increase” of botnets that “are impacting Venezuela.” He explained that a hive of bots was being maliciously operated in the Venezuelan cyber atmosphere amid the election.

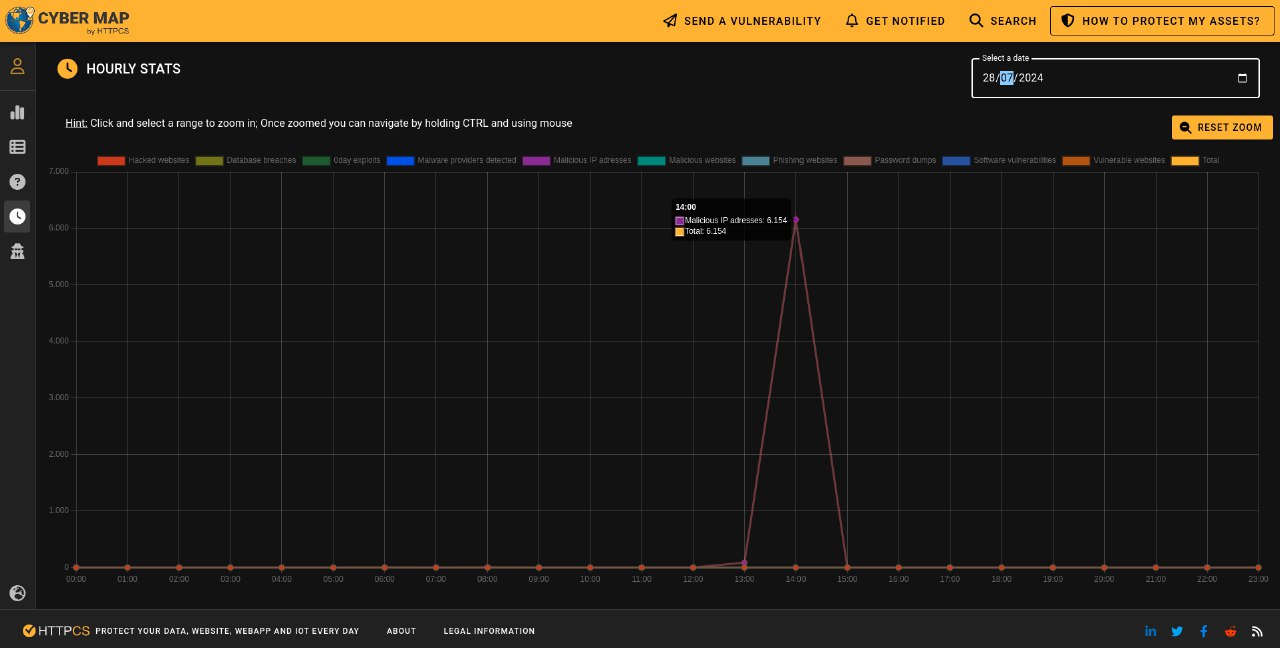

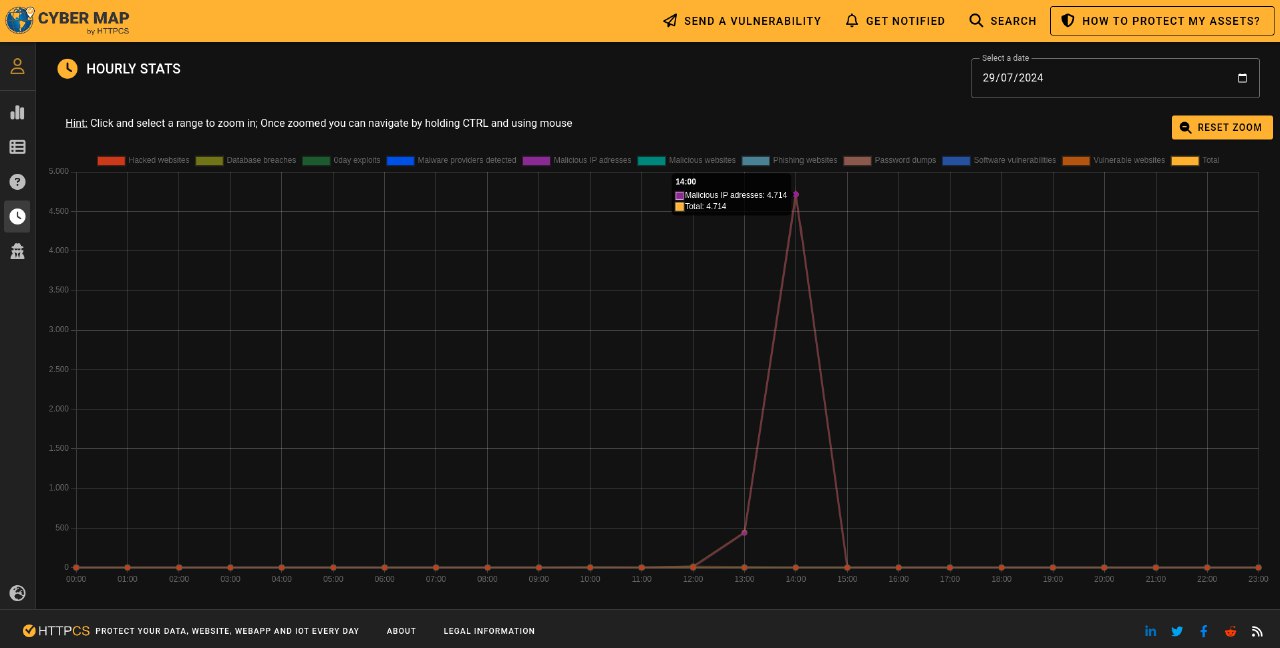

In another post, the computer expert mentioned that there was “a peak of malicious IP addresses between 12:00 and 3:00 p.m. on July 28 (6,154 IPs) and 29 (4,714 IPs).” He added that these were “IPs for command and control of botnets, spam, DDoS attacks, etc.” The data is taken from Ziwit’s HTTPCS.

On the morning of July 29, President Maduro reported that there was intense malicious activity of bots in favor of far-right opposition candidate Edmundo González Urrutia and a cyberattack against the CNE transmission system, which caused the slowdown in the counting of votes and transmission of election results.

This cyberattack created a breeding ground for DDoS attacks on websites of some Venezuelan institutions, including that of the CNE, making these websites inaccessible.

Side fact: Misión Verdad’s website was hacked on the morning of election day, so it was unavailable for a few hours. Regular readers of the website can attest to this.

The objective of these swarm attacks can vary, but they often intend to steal confidential information and cause damage to the target’s infrastructure.

The Ministry of Science and Technology explains that “a bot attack is a type of cyberattack that uses automated scripts to disrupt a site, steal data, make fraudulent purchases, or perform other malicious actions. These attacks can be deployed against various targets, such as websites, servers, APIs, and other endpoints.”

All this indicates that Venezuela was indeed saturated with cyberattacks. In addition, there was an attempted electoral blackout: a scenario that requires a high level of security and seriousness in an era where the cyber domain dominates and is of critical and daily use.

A technician’s explanation

It should be highlighted that the reported attack against the CNE system targeted the transmission of data. This does not affect the content of the data since the security mechanisms guarantee its integrity. The results transmitted cannot be altered, but the attack affected the transmission of information.

The delay caused has been remarkable since, according to IT specialist and external auditor of the CNE Victor Theoktisto, the attacks “reduced the connections in such a way that they were rarely completed successfully, slowing down the whole counting process.”

In conversation with Sputnik, Theoktisto explained that “communication between the voting machines and the Totalization Center is based on a WAN [Wide Area Network] provided by the Venezuelan national telephone operator through the telecommunications network that transmits telephone line data [Dial-up], Metro Ethernet, and GSM service or via satellite in remote areas.”

“The transmission network used is exclusive for the electoral process and does not use the Internet,” he added. “All this is extremely secure and encrypted, making it impossible to alter the transmitted data.”

Since the CNE has a system to back up the vote, possesses all the electoral minutes that, as stated in the first bulletin of July 29 at dawn, certify that Nicolás Maduro won the presidential election.

As for the transmission system, the specialist supports President Maduro’s request to the Council of State and the National Defense Council on July 30 to shield the integral security of the electoral technological domain. “Obviously, it will be necessary to use alternative equipment and protocols with greater redundancies to avoid a repetition, including more drastic measures to preserve the security of the transmissions,” Theoktisto commented.

Although Venezuela has an electoral system shielded against frauds of any kind, unlike, for example, the United States and the United Kingdom, the vulnerable flank (transmission system) was undoubtedly attacked with partial success, a technical detail that has been key to the present coup scenario led by María Corina Machado.

Origin of the cyberattacks: North Macedonia

Venezuelan authorities reported that the cyberattacks came from North Macedonia, a country located in the Balkan peninsula, a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) since 2020, and a candidate to join the European Union (EU) since 2005 after splitting from Yugoslavia in 1991.

It is one of the countries that, for a good part of the 20th century, was in the European socialist orbit and is now part of the multinational military organization led by the United States.

In recent years, the refreshed ties between North Macedonia and the United States have consolidated a bilateral relationship of such magnitude that USAID has dozens of active programs throughout the country. The U.S. embassy in the capital, Skopje, also maintains close relations with state and private institutions alike, in addition to close military ties.

Both countries share intelligence information and have a joint program in cybersecurity matters, a collaboration that began in 2018 and is overseen by the U.S. Cyber Command.

It is worth mentioning that in February, a new commander took charge of that branch of the Pentagon, General Timothy Haugh, who is also in charge of the National Security Agency (NSA), the U.S. institution overseeing the cyber domain and whose espionage scandals and malicious activities have gone beyond the limits of its own country.

Haugh announced in April that the U.S. military’s Cyber Command has worked in some 20 countries in the past year under a “proactive approach” and in a secretive manner, including North Macedonia.

North Macedonia’s cyber activity, under U.S. tutelage, is mainly focused on an anti-Russia agenda within the context of the war in Ukraine and Donbass. The agenda was prepared by the experts of the Cyber Command during the Trump era.

Another side fact that is not minor: the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) maintained (or still maintains) a clandestine detention center (black site) in Skopje, a secret prison financially assisted and run by the U.S. spy agency. This collaboration became known in a report published in 2007, evidencing the close ties between North Macedonia and the United States.

As a NATO member, North Macedonia’s military structure is integrated into NATO. Its request to join the EU has also been accompanied by military adjustments according to the delimitations of European legislation.

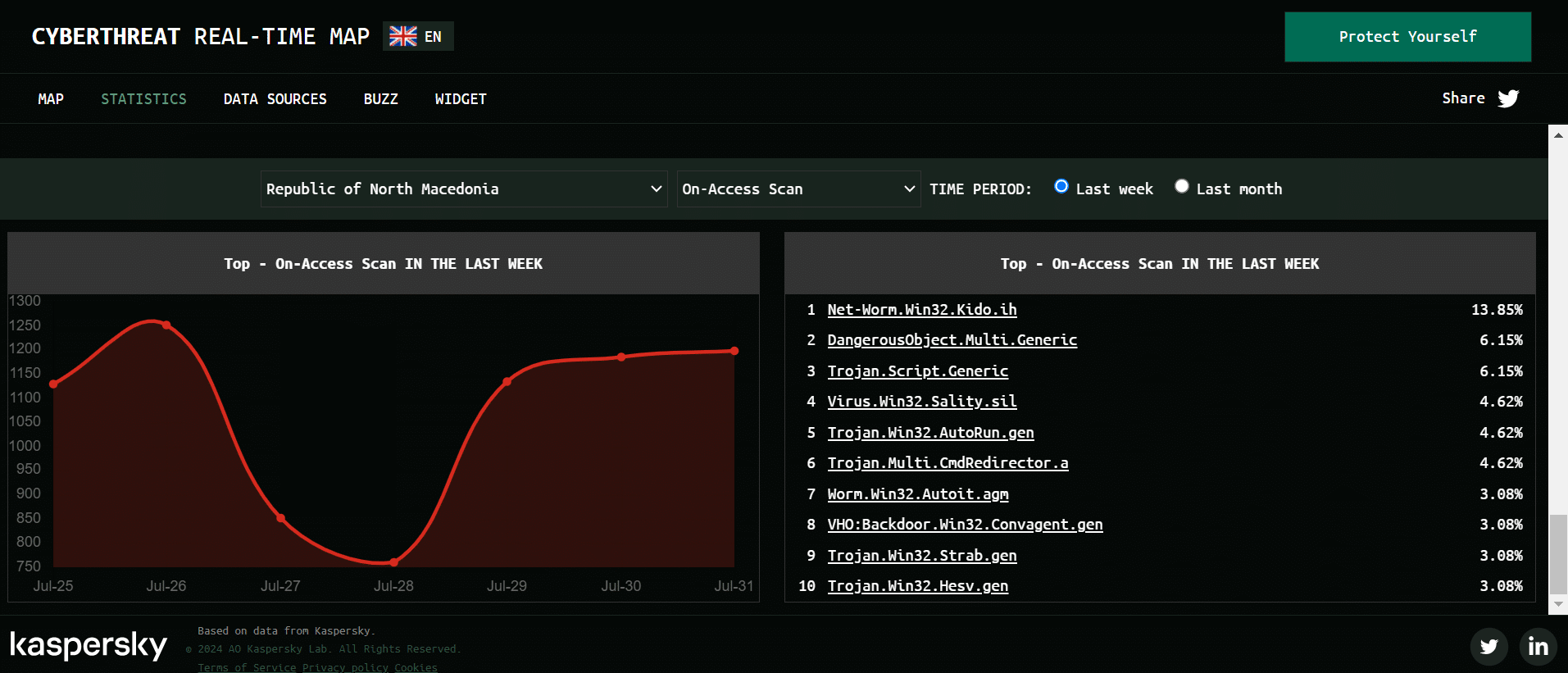

The Venezuelan authorities’ accusation was not against the government of North Macedonia. It was only alleged that the cyberattacks came from the country. According to the Kaspersky Cybermap, malicious cyber activity from North Macedonia increased significantly on July 28, peaked on July 29, and exhibited a stable trend in the following days.

These data broaden the perspective on the cyberattack against the CNE, an attempt to throw the electoral system into chaos to benefit the coup agenda of Machado & Co.