H. Bruce Franklin, who died on May 19, 2024, at the age of 90, ranks among the great public intellectuals of our time. He exerted incalculable influence as a teacher and activist and left an immense legacy as a scholar. Those of us who knew him will never forget him, and those who encounter him in years to come through his writings and recorded interviews—like the superb one with Doug Storm that Monthly Review published in September 2022—will continue to learn from him.

As a teacher, Bruce pushed his students to think in unaccustomed ways and encouraged them to fulfill the potential they did not know they had. I can testify personally to both, having taken his honors freshman English and advanced Hawthorne and Melville courses at Stanford University in the spring and fall of 1963. “Dr. Franklin, I’m confused,” I remember complaining during an office consultation freshman year. “That’s a good sign, Miss Lury,” he replied. By the following year, my confusion had apparently led to the intellectual growth Bruce was seeking to stimulate. When I produced a term paper for his Nathaniel Hawthorne and Herman Melville course that met his high standards, he did not simply give me an A, but wrote in his final comment: “I exhort you to publish this splendid paper.” He then suggested a journal, explained how to go about submitting to it, read two further drafts of the paper over the following quarter, and wrote to congratulate me when the journal accepted it. Typifying Bruce’s teaching style, which benefited thousands of students during a career that lasted more than six decades, this example also illustrates how unique Bruce was in taking his female students seriously as professionals long before the feminist movement started.

Even though Bruce had not yet embraced Marxism at this early stage of his career, and even though I left Stanford to get married, he shaped my consciousness so profoundly that he became my lifelong mentor. My thinking evolved over the years along lines he inspired, whether or not I was directly in contact with him. Once we were back in regular contact with each other, he read and critiqued almost everything I wrote until a few weeks before his death.

It was, of course, the Vietnam War that transformed Bruce’s own consciousness, as he details in his last and greatest book, Crash Course: From the Good War to the Forever War (2018), which artfully interweaves personal memoir, political analysis, and historical scholarship. Bruce’s activism against the war took many forms: he supported and spoke at campus protests, campaigned along with his wife Jane among workers and in the surrounding community to stop the production of napalm in a factory near Stanford, joined likeminded professors to make the Modern Language Association take a stand against the war, worked in Paris with Vietnamese students while helping deserters from the U.S. army in Vietnam escape to safe destinations along a latter-day underground railroad, and participated in the multiracial revolutionary organization Venceremos. Whatever form of activism Bruce undertook, he consistently tried to forge alliances across barriers of sectarianism, class, and race. One of his most successful enterprises was persuading some striking steelworkers, who had previously voted for the presidential candidacy of white supremacist Alabama Governor George Wallace, to defend the Black Panthers with arms against a threatened police raid. Decades later, Bruce would similarly mobilize otherwise conservative white working-class recreational fishers to agitate against the commercial menhaden industry that was destroying the ecology of the Atlantic coast.

Ultimately, Bruce left his most enduring legacy as a scholar, publishing a total of twenty-one books and hundreds of articles in venues from academic journals to online outlets. Among the twenty-one books are five that distill his scholarship into anthologies aimed at introducing students and the general public to writings from which they can derive their own understanding of the many-faceted struggle against war, racism, and sexism raging around them: From the Movement Toward Revolution (1971), Countdown to Midnight: Twelve Great Stories about Nuclear War (1984), Vietnam and America: A Documented History (with Marvin E. Gettelman, Jane Franklin, and Marilyn B. Young, 1985; revised edition, 1995), The Vietnam War in American Stories, Songs, and Poems (1996), and Prison Writing in 20th-Century America (1998).

In reviewing Bruce’s enormous output, I am struck not by the rupture that occurred when the movement against the Vietnam War revolutionized his life in the mid-1960s, but by the continuities between his earlier and later scholarship. Although no reader of Bruce’s first book, The Wake of the Gods: Melville’s Mythology (1963) could have predicted that he would shift his focus to the Vietnam War and the arms race, a glance at his major works in these areas—War Stars: The Superweapon and the American Imagination (originally subtitled “The Myth of the Superweapon in American Culture”), M.I.A or Mythmaking in America, and Vietnam and Other American Fantasies—shows that he remained centrally concerned with mythmaking as both a cultural and a literary phenomenon. The continuity between Bruce’s second book, Future Perfect: American Science Fiction of the Nineteenth Century, and War Stars is even more obvious: the books probe U.S. fascination with technology and analyze the psychosexual and militaristic fantasies that authors of science fiction sometimes unconsciously express and sometimes consciously explore. Even Bruce’s next-to-last book, The Most Important Fish in the Sea: Menhaden and America, which itself marks a shift from militarism to environmentalism as a central concern, reveals such continuities. Not only does it quote Moby-Dick, but many passages of it display the same lyricism and epic grandeur as Melville’s masterpiece and intertwine literature, science, and cultural history in similar ways.

As I look back through The Wake of the Gods, sixty-one years after its publication secured Bruce a national reputation as a Melville specialist and literary scholar, I still find it compelling. The chapters on Moby-Dick, Benito Cereno, and Bartleby, the Scrivener, in particular, retain remarkable traction, as attested by the number of critical anthologies and casebooks in which they have appeared, the Bartleby essay as recently as 2002.

It is not in The Wake of the Gods, but in Future Perfect, however, that one sees the Bruce Franklin we know today beginning to emerge. Future Perfect took U.S. literary scholarship in a daringly original direction by initiating the serious study of science fiction as a genre. Contending that virtually all of the U.S. top-ranking writers and most of those in the second rank produced at least “some science fiction,” the first edition of 1966 anthologized stories by Hawthorne, Edgar Allan Poe, Melville, Edward Bellamy, Ambrose Bierce, and Mark Twain, as well as by a host of unknown writers, intercalating them with critical essays on the stories and the subgenres to which they belong, such as time travel, dimensional speculation, and automata. Subsequent editions have incorporated a broader selection of stories, including some by women. Currently in its fourth revised and expanded edition, Future Perfect is still being used in classrooms—a rare feat for a book first published fifty-eight years ago. When I say that the Bruce Franklin we know today begins to emerge in Future Perfect I am referring especially to the essay introducing Melville’s “The Bell-Tower,” then largely neglected. Bruce reads “The Bell-Tower” as a “complicated political allegory” about slavery and its consequences. The “automaton stands for all kinds of slaves,” he explains, “from the African Americans in the south to the machines and their slaves in the North”; correspondingly, its creator, Bannadonna, represents the “unwitting agent of the self-destruction which ensues from manacling the hands and feet of others.”

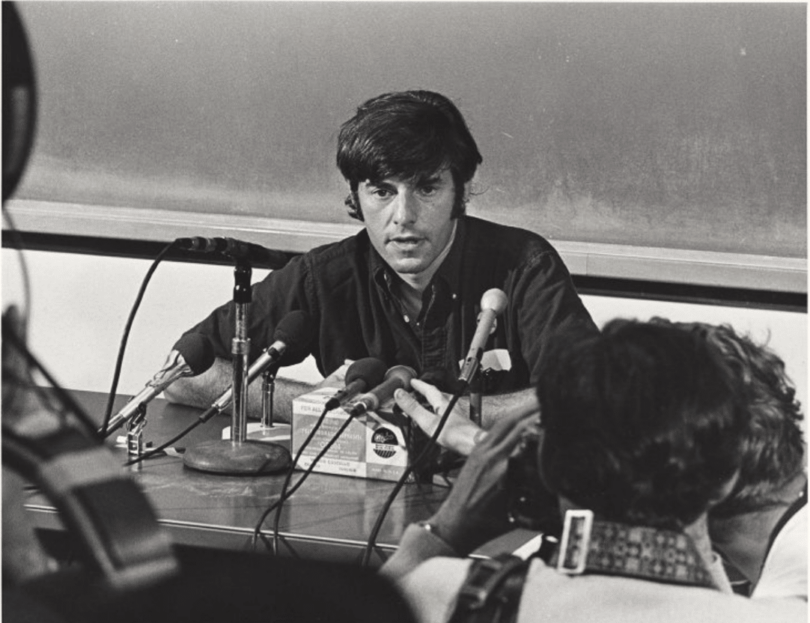

By the time Bruce published Future Perfect, he was already deeply involved in the antiwar movement. His courageous activism ultimately cost him his job in 1972, when Stanford fired him despite his tenure, in a case that made national headlines. While interrupting and threatening to end his academic career, his participation in the antiwar movement nonetheless laid the groundwork for his subsequent scholarship. The link to his four books on the Vietnam War and his penetrating critique of militarism in War Stars is self-evident. Less evident is the role that his close contacts with the Black Panthers and his collaboration with other radicals of color played in generating the interest in prisons and prison literature that shaped his revolutionary book, The Victim as Criminal and Artist: Literature from the American Prison (1978).

Consider this statement from the third page of the introduction: “Insofar as American literature is in fact a unique body of creative work, what defines its identity most unequivocally is the historical and cultural experience of the Afro-American people.… When we grasp the significance of this truth for American literature as a whole, we will be forced to change radically our critical methodologies, our criteria for literary excellence, and our canon of great literature—or perhaps even the entire notion of a canon.” Notice how Bruce here prophesies the next quarter century of scholarship. One thinks immediately of the brilliant challenges that Jane Tompkins, Barbara Herrnstein Smith, Barbara Foley, Houston Baker, Henry Louis Gates, and above all Paul Lauter soon formulated to prevailing critical methodologies and aesthetic criteria. And of course, one thinks as well of the monumental work that did more than any other to change “our canon of great literature” and “our very notion of a canon,” Lauter’s Heath Anthology of American Literature. Bruce himself never fails to point out that hundreds of other academics underwent the same transformation of consciousness he did during the ferment of the 1960s’ protest movements, and he consistently pays homage to the radical scholarship that influenced his own, particularly the essays published in the “seminal” 1972 collection edited by Paul Lauter and Louis Kampf, The Politics of Literature.

Yet to acknowledge this influence is not to deny that The Victim as Criminal and Artist is a paradigm-shattering book. Bruce does not simply prophesy the radical reconceptualization he says must occur—he also models it. Victim begins with a survey of anthologies and how they have operated to “encompass no more than belletristic writings by a select handful of white authors” (as he puts it). After that, the opening chapter provides two of the earliest literary analyses of Frederick Douglass’s Narrative and Harriet Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl—texts that were at the time completely ignored by the white literary establishment, though they now feature in everyone’s syllabi and have spawned veritable critical industries. The third chapter goes on to rewrite the history of U.S. poetry by arguing that “Afro-American music and poetry…has formed the most distinctive and influential tradition within American literature”—a “tradition which represents the unique major contribution American poetics has made to world culture” (29). In between, Bruce sandwiches a chapter on Melville titled “The Worker as Criminal and Artist.” It rereads Melville through the lens of narratives and songs by African-American slaves. In the process, it reveals a Melville few had ever seen before: “an artist whose creative imagination was forged in the furnace of his labor and oppression, an artist who saw the world of nineteenth-century American society and its commercial empire through the eyes of its victims” (34). Once again, Bruce here sets a new direction for literary studies. For the past few decades, most Melville scholars have been testing and refining this thesis, although it was deemed positively heretical when Bruce first enunciated it.

Bruce’s own subsequent essays on Melville have pursued in depth interpretations sketched briefly in Victim and have sometimes gone well beyond them. “Past, Present, and Future Are One” masterfully unravels the convoluted historical knots of “Benito Cereno” that tie together Columbus’s so-called “discovery” of the New World; the “metamorphosis of Spain into the first truly global empire”; the Spanish Inquisition as “a crucial instrument of imperialism and racism”; the American and French Revolutions; the St. Domingo slave rebellion; and the aggressive expansion of the U.S. slave empire in the 1850s. “From Empire to Empire: Billy Budd, Sailor” shows how Melville’s posthumous novella, “by going a century into the past to explore the consequences of the triumph of militarism and imperialism in England…foreshadows the century of the future, with the consequences of the triumph of militarism and imperialism in America” (213). Most startlingly, “Billy Budd and Capital Punishment: A Tale of Three Centuries” reveals a totally new dimension of this much debated work: “Like many of his contemporaries,” argues Bruce, Melville “saw that the essence of capital punishment is the state’s power over life and death, a power boundlessly expanded in war. He dramatized the deadly meaning of capital punishment for the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries in the kidnaping of Billy Budd from the Rights of Man and his execution on the aptly named Bellipotent.”

It is impossible to read these words, written in 1997, without recognizing their relevance to the George W. Bush era, with whose consequences we are still living in 2024, the year of Bruce’s death. We still confront the legacy of a president responsible for more executions than any other in our previous history, of a political clique that indeed kidnapped us from the Rights of Man by foisting the Patriot Act on a nation blinded by fear, and of an oppressive state power “boundlessly expanded in war” with no end in sight. Indeed, as Bruce reveals in his stunning capstone book, Crash Course, a “Forever War” stretching across the globe and fueled by the same lies about spreading democracy has now replaced the Cold War that mired us in Vietnam. With it, “an increasing flow of veterans of our various wars,” many “traumatized by combat,” filled his classes until his retirement at age 83 (273). Some would pass on to their children what they learned in Bruce’s courses, others would encourage their children to take his courses, and a few would emulate his model of politically engaged scholarship and teaching.

What best sums up the enduring achievement of Bruce’s long career as a scholar is his extraordinary gift for teaching us to read our history in our literature and to glean from both insights that can help us alter our future.