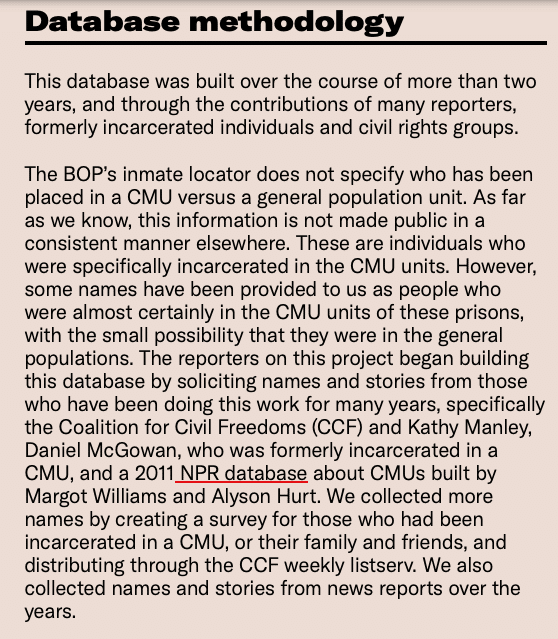

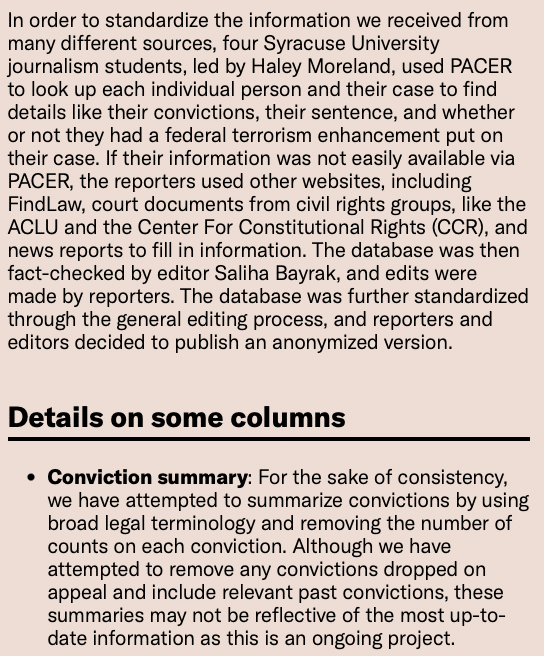

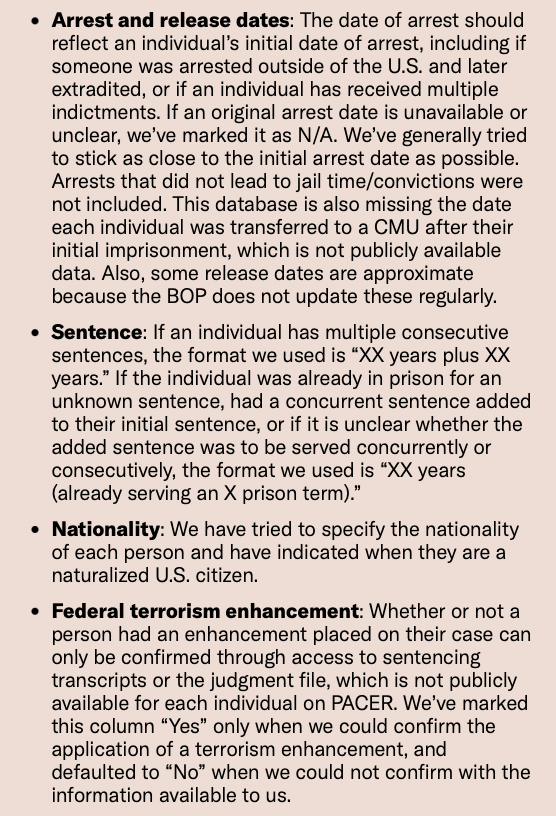

This story was produced in partnership with The Nation with assistance from students at Syracuse University and the Data Liberation Project.

Months after being incarcerated for his role in one of the biggest American whistleblowing cases in recent history, Daniel Hale suddenly went silent. Hale’s family and friends, who had been in regular contact with him after his 2021 trial, didn’t hear from him for several days. The judge in his trial had recommended that he go through a mental health treatment program in North Carolina, and be placed somewhere near his support network in Virginia, according to sentencing documents from his case. His friends and attorneys were baffled at his disappearance until another incarcerated person found a way to tell them he’d been transferred.

Then Hale’s friend, Noor, received a call from a federal prison in Marion, Illinois.

“The first thing he says to me,” she recalled,

is, ‘Don’t say anything, don’t say anything. Just listen.’

Hale told Noor, who asked to be identified by her first name only, that he had been transferred to a Communication Management Unit (CMU) in Marion. He gave her the basics: at the CMU, their calls would be live-recorded and all his communications would be closely monitored; she couldn’t put him on speaker phone because the call would be cut; he’d be able to speak to her that day for only 15 minutes, and he needed all their friends’ phone numbers so that he could try to get them approved as contacts; he wasn’t allowed to give her messages for other people.

Noor had spoken to Hale a number of times after he was sentenced to almost four years in prison for leaking classified documents about the U.S. drone program and its civilian casualties. But most of those calls had taken place while Hale was in county jail, awaiting a prison placement. Now that he was in the federal prison system, it was clear that everything would be different.

After the call, Noor started researching CMUs. She quickly learned that the units, sometimes called “Little Guantánamo” or “Guantánamo North,” were originally built to house people the federal government alleged had connections to international terrorism. The units, located as separate sections within two federal prisons in Marion, Illinois, and Terre Haute, Indiana, consist of single cells where people are isolated and subjected to intense surveillance and monitoring. People in CMUs have much less access to the outside world because of their status. They have extra limits on visits, phone calls, emails, and even postage mail. They can communicate only with approved contacts, and all communication is meant to be monitored.

Noor, who has been friends with Hale for more than a decade, said she didn’t know why someone whose crime involved no violence would be placed there.

“I don’t know the extent to which they were monitoring Daniel,” Noor said.

But maybe, they were like, let’s teach him a lesson, and make sure that he isn’t able to use his voice again.

Hale’s case stands out among the hundreds of others incarcerated in CMUs. The federal government quietly opened the two CMUs in 2006 and 2008 under a cloud of secrecy. There was no public hearing beforehand, and no apparent guidelines on the criteria authorities would use for placement in the units. When the CMUs opened, 70 percent of those incarcerated in them were Muslim men, who made up just six percent of the overall federal prison population at the time. This statistic was so startling that it became a key part of at least two separate lawsuits filed against the Bureau of Prisons (BOP) in 2009 and 2010 regarding CMU conditions and due process. Both cases were eventually dismissed because plaintiffs settled out of court or were released from the units, rendering their cases moot.

In addition to the critiques of CMUs as an Islamophobic manifestation of the U.S. “War on Terror,” advocates have raised concerns that the units are often used to punish those who have expressed a strong opposition to American foreign policy—as Hale did so publicly.

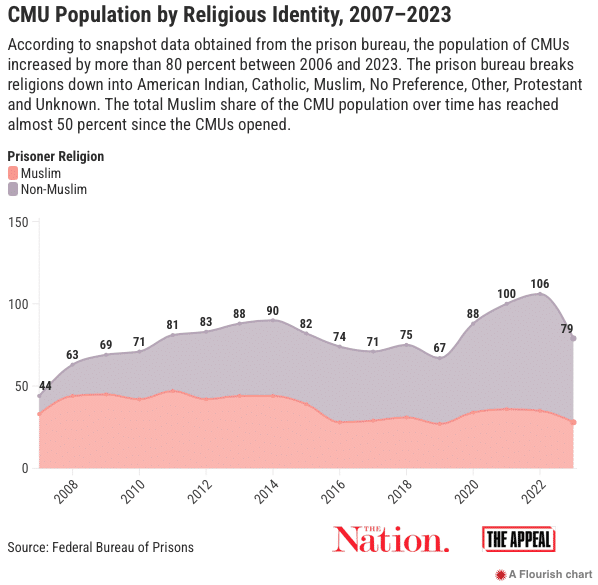

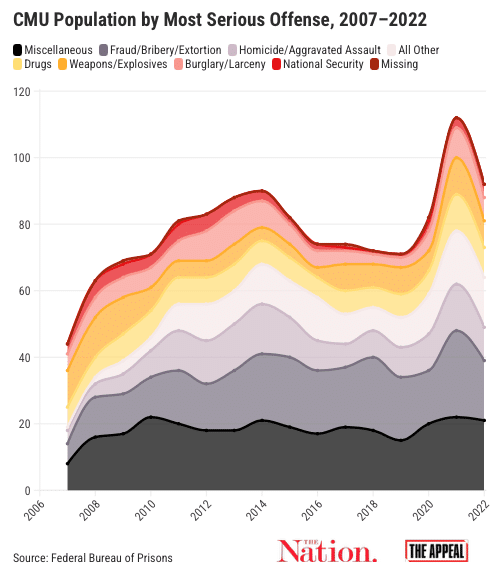

An investigation of BOP data by The Nation and The Appeal now suggests the federal government is expanding its use of CMUs, including with plans to build a new unit at a facility in Maryland. According to the most recent data, obtained by public records request, the number of people incarcerated in CMUs between 2007 and 2022 increased by 140%. Although the share of Muslims incarcerated in the units has decreased over time, that is largely due to the growth in the overall population. As of 2023, Muslims still made up 35% of the total CMU population.

Noor, who works as an organizer in Washington, D.C., said she is worried that CMUs will increasingly be used to incarcerate whistleblowers like Hale, who have been prosecuted for exposing violent U.S. policies.

Hale served in the Air Force and was stationed in Afghanistan from 2009 to 2013. It was there that he would experience what he called in a letter to the judge in his case “the most harrowing day of my life.” In 2012, a drone strike that he and his superiors deployed hit not only a man they were tracking, but also his wife and their two daughters, only three and five years old, resulting in the death of their eldest.

Two years after this incident, Hale leaked classified documents about the U.S. drone program to a reporter. The resulting investigation, published by The Intercept, revealed the shocking number of casualties caused by drone warfare, and the flawed methods the government used to identify targets. Hale said his role in the strike on this family and his participation in the drone program pushed him to release the documents.

“The determined fighter pilot has the luxury of not having to witness the gruesome aftermath,” Hale wrote in the letter,

but what possibly could I have done to cope with the undeniable cruelties that I perpetuated?

In July 2021, more than two years after his arrest, a federal judge sentenced Hale to 45 months in prison for violating the Espionage Act. He was released earlier this summer.

Hale did not respond to emails regarding this investigation.

In January, the BOP inked a $2.8 million contract with Virginia-based construction company PROCON International to convert a medium-security prison in Cumberland, Maryland, into a CMU. PROCON CEO Aziz Elham confirmed the conversion project in a text to The Nation and The Appeal, though neither he nor a BOP spokesperson would give further details. It remains unclear how many CMU cells the unit will contain, or if this is meant to be an additional unit or a replacement for existing units in the two other BOP facilities. In 2019, a federal prison in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania was scheduled for a mission change to become a CMU. According to the BOP, the change was never implemented.

An expansion of the CMU program may have always been the plan. According to a 2020 OIG audit of the BOP’s abilities to monitor incarcerated people, the agency had intended to establish up to six CMUs in order to better monitor “terrorist inmates.” The report, which, among many other aspects of monitoring, criticized the BOP’s list of who is or is not considered a “terrorist,” said that CMU equipment is “insufficient for BOP staff to perform adequate monitoring of certain terrorist inmate conversations.” The audit consisted of interviews with BOP staff and was conducted to “prevent further radicalization within inmates.”

In response to early scrutiny—including from members of Congress—over the high population of Muslims in CMUs, the BOP opened up public comment periods in 2010 and again in 2014. In 2015, the agency finally defined its policies for CMU placement, stating that connections to international or domestic terrorism were key justifications.

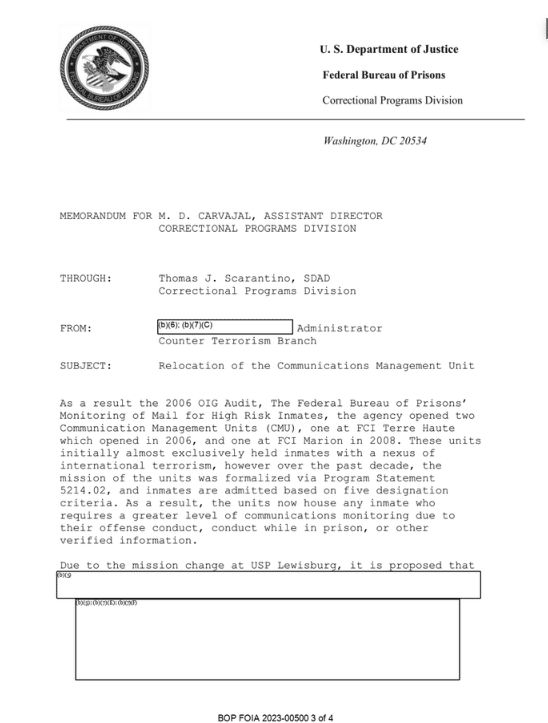

But internal BOP documents obtained by The Nation and The Appeal via public records request show that, despite recent criticism that the BOP is not even effectively monitoring those it has already incarcerated in CMUs, the agency has widened its criteria for CMU placement over time. CMUs are going from housing “almost exclusively” people judged by courts to have a connection to international terrorism, to housing “any inmate who requires a greater level of communications monitoring.” The change in purpose of these units has resulted in some bloating, which has seen some people incarcerated in the units, like Hale, who the government admits have no ties to terrorism or even violence.

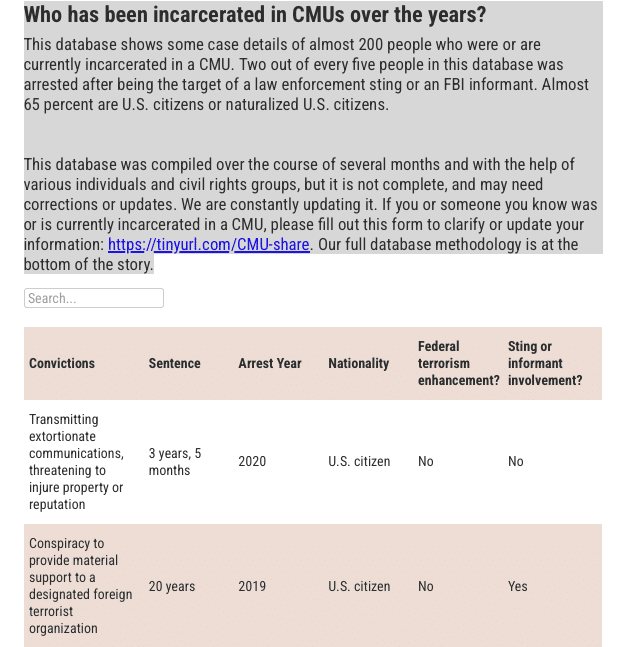

The BOP has not published comprehensive data about who has been incarcerated in CMUs over time. To get a better picture of the CMU population and how it’s changed, The Nation and The Appeal created a database with the convictions, nationalities, and certain case details for those previously or currently incarcerated in one or both of the units. An analysis of this database of almost 200 people, which reporters continue to build, shows certain trends: about one-third of the individuals in the database have no alleged affiliation with a terrorism group. This is in line with the 2020 OIG report, which criticizes the BOP for being unable to correctly identify those with a “known nexus to domestic or international terrorism.”

One-third of individuals in our database were arrested within the four years after 9/11. (Because the database was compiled partially with the help of advocates who work with those targeted by “War on Terror” policies, the data may be skewed toward Muslims and those who have been accused of having connections to foreign terrorist groups, whether or not those accusations were true.) The database also sheds light on law enforcement’s controversial use of informants and sting operations, as two out of every five CMU detainees in this database were arrested after being targeted by these sorts of tactics. These strategies have been criticized by Human Rights Watch and others for preying on the vulnerable, including youth, individuals with mental health issues and undocumented people, and for encouraging their targets to commit acts that would be categorized as crimes. Sting operations and the use of FBI informants have increased after 9/11 and have resulted in many people being labeled “terrorists” who did not actually engage in any violent acts.

The label of “terrorism” has accumulated racial meanings over time, and has been used to justify state violence, writes race and terrorism scholar and Carleton University professor Atiya Husain. The U.S. government and federal courts have expanded this definition in the post-9/11 era to target charity, speech, and as a tool to wield state power against those that come into the government’s disfavor. Mentions of “terrorism” in this database or in our investigation refer only to the U.S. government or federal court interpretations of terrorism.

A 2015 program statement says CMU designation is “non-punitive” and that referrals to a CMU can come from a counterterrorism unit, as part of a person’s sentencing computation, or from other law enforcement agencies. Beyond mentions of terrorism, the document states that someone can be designated to a CMU if there is “a substantial likelihood” they will engage in illegal activity through communication, or that they will contact their victims. It also contains more open-ended criteria for designation based on “any other substantiated/credible evidence of a potential threat to the safe, secure, and orderly operation of prison facilities, or protection of the public, as a result of the inmate’s communication with persons in the community.”

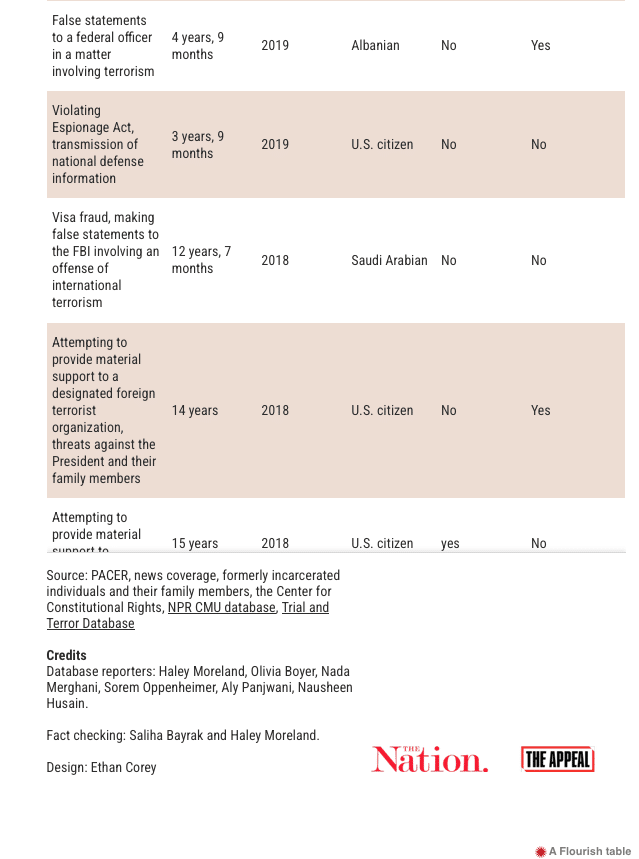

Despite pending FOIA requests, the BOP has yet to release documents with additional information on people incarcerated in CMUs, including their underlying convictions and official justifications for placement in the units. In snapshot data obtained from the BOP last year, the highest share of people incarcerated in both CMUs each year had been convicted on charges categorized as “Fraud/Bribery/Extortion” or “Miscellaneous.” The only outlier year was 2007, when 11 out of the 44 people detained in the Terre Haute CMU had been convicted on “Weapons/Explosives” charges. “National Security” offenses are consistently at the bottom of the list for frequency each year.

A BOP spokesperson denied a request for an interview on the agency’s use of CMUs, stating that the office does not “interpret or research the data received through FOIA requests.”

One of the frustrating aspects of CMUs is that it’s difficult to predict who could end up in one, said Kathy Manley, an attorney who has been working with clients held in the units since they opened. She also said she’s not surprised by the expansion of CMUs beyond their initial use primarily to punish Muslim detainees.

“One of the things that always happens is that they’ll target a particularly hated group of people for new repressive projects,” said Manley. “Muslims convicted of terrorism or sex offenders—nobody cares about them so we can take away some of their rights and say that it’s for national security purposes.”

Once established, she added, “we can keep expanding those norms through the rest of society.”

Manley has worked with clients in prison, some within CMUs, for more than 15 years. She said clients complain about arbitrarily being thrown into solitary confinement with no disciplinary charges filed, being moved between units at Marion and Terre Haute or transferred to the supermax prison for no clear reason, or being threatened with a transfer to a CMU if they want to challenge a disciplinary charge. One of Manley’s clients sued the BOP after he got sick following a stint in “the hotbox,” a particularly hot area of the Terre Haute CMU, which does not have air conditioning. Another client swallowed a razor blade out of frustration at not being able to transfer out, she said.

Earlier this year, Manley and another Coalition For Civil Freedoms attorney had been denied legal calls with CMU clients. BOP officials told her they couldn’t connect them unless they had an imminent court deadline, and that the attorneys could visit instead.

The lack of communication from within CMUs also means the outside world has less information about the conditions and treatment of those inside.

Rachel Meeropol, former attorney at the Center for Constitutional Rights, the civil rights organization that filed the 2010 lawsuit challenging CMUs, said the program’s nebulous placement criteria makes it ripe for abuse. She and other civil rights advocates have expressed concern that dissent is increasingly being categorized as “terrorism” for the BOP, and the CMUs are an example of this bloating.

“These units exist out there in a way that is very open to abuse in the future, and can be used against any politically unpopular group that comes into particular disfavor,” she said. “The way we saw them used against Muslims … it can be used in this way as a political prison.”

Environmental activist Daniel McGowan first heard about CMUs in 2007, as he and his legal team attempted to fight a federal terrorism enhancement tacked onto his case. While he ultimately lost this battle, resulting in a seven-year sentence for conspiracy and arson, the terrorism enhancement did not immediately land him in a CMU.

While incarcerated at FCI Sandstone, a federal prison in Minnesota, McGowan worked on a Masters degree in sociology and regularly wrote blogs and papers criticizing the U.S. prison system. He knew the BOP was watching him closely, both for his writing and the stream of mail and visitors he received from the outside.

One day in 2008, without any notice, McGowan was told to pack up. The guards didn’t tell him where he was going until he was on the bus—“Marion,” they said. “Terrorist unit.”

The BOP cited McGowan’s writing as proof of his continued support for “radical environmental terrorist groups.” CMU transfers tend to be “a fly-by-night affair,” said McGowan, which allows the BOP to ship people off to these restrictive facilities with very little recourse. He spent much of the next four years in CMUs at both Marion and Terre Haute. In 2013, after McGowan’s release from prison to a halfway house, he wrote about his experiences with CMUs in a piece for HuffPost. McGowan says he was arrested at his halfway house and briefly jailed after publishing it.

The use of CMUs to punish critics of the United States has always been a cornerstone of the program, activists and formerly incarcerated people say. Many Muslims have landed in CMUs after speaking up against “War on Terror” policies, or indicating belief in certain Islamic principles.

Relying on broad policies for Muslims specifically was the original basis of the program since its inception, said University of Colorado law professor Wadie Said. The BOP established the units in response to criticism for allowing three men convicted of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing to send letters in Arabic, to outside contacts. These letters, some of which were sent to “members of a Spanish terror cell,” according to a 2006 report from the Office of the Inspector General about the incident, were perceived to be a security threat. Because of this incident, the report recommended the BOP to consider applying special administrative measures, including enhanced surveillance, for anyone convicted of terrorism-related crimes, among other surveillance methods.

To Said, author of a 2015 book on terrorism prosecutions, the presentation of CMUs as a necessary response to “dangerous terrorists” follows a trend of sweeping, over-broad policy responses from the post-9/11 era.

“The thing about the terrorist angle is that it’s always an opening to put in place a holistic policy,” said Said. “Some guy tried to blow up a plane with his shoes, now we have to take off our shoes. Not individual, not more focused. Everyone is now affected.”

After his friend died from a burst appendix at FCI Butner, Andrew Stepanian and other members of his prison soccer team sent petitions to the BOP protesting their frustration with what they felt was an avoidable death. Shortly after, the BOP transferred his entire soccer team to different facilities across the country. Stepanian was sent to CMU Marion, where he served the last months of his federal sentence in 2008.

Stepanian was notified many days after his transfer that he had been sent to the CMU because of his affiliation with “domestic terrorist organizations.” He believes it was at least partly retaliation for raising grievances about negligence surrounding his friend’s death.

For Muslim men incarcerated in the CMUs, the risk of being punished for being “too radical,” with little explanation of what that actually means, is ubiquitous. This was the consistent throughline between Asif Salim’s case, incarceration and CMU detention.

When Asif Salim was incarcerated in a New Hampshire federal prison just miles from Mount Washington, he was put in solitary confinement for three months. Salim, who is Muslim, said prison officials told him he was being punished for having a book called “The End of the World: Signs of the Hour, Major and Minor.” He hadn’t faced any disciplinary actions before or after that, and at the time, he had no idea how long he’d be held there. Salim said BOP staff were concerned about his educational influence among the prison’s Muslim community, which was also a reason given for his later transfer to a CMU.

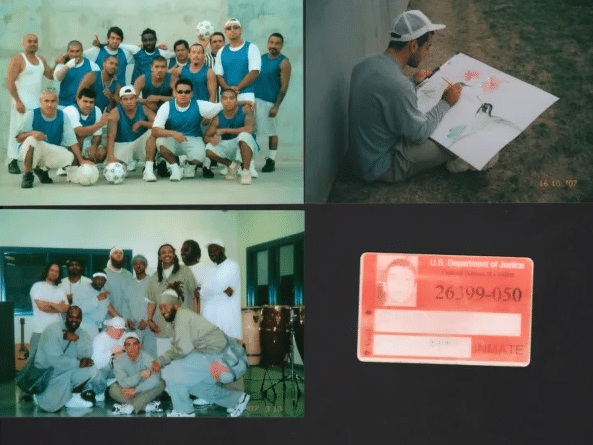

Salim in the Marion CMU. Photo courtesy of Salim.

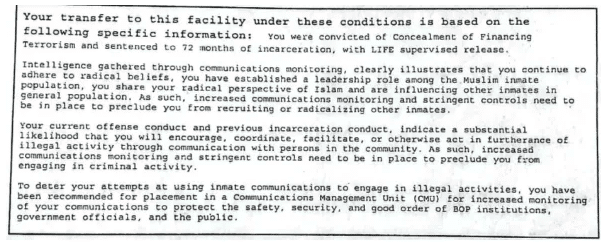

Salim was convicted in 2018 of “concealment of funds used to support terrorism.” The charges stemmed from a $2,000 check he’d sent to a friend in 2009, which he said was for his fishing supply business. Salim wasn’t arrested until 2015, and the government alleged the check from 2009 was part of a conspiracy to eventually send $22,000 to Anwar Al-Awlaki, the Yemeni-American preacher who was placed on the U.S. terror watch list in 2010, and subsequently killed in an American drone strike the next year. A fact that was not contested by either side was that Salim had had no contact with Al-Awlaki nor anyone in a terrorist organization, and he has denied participating in any kind of criminal activity. The case relied heavily on emails between Salim and three friends and, in an attempt to dismiss the case, his lawyers clarified that out of 18 emails where Salim was included, he was blind carbon-copied (BCC’d) on most of them with no comment from him. The government dropped their initial indictment and Salim, facing pressure at the time, eventually agreed to a plea deal on concealing funds with a sentence cap of eight years. He was sentenced to six years.

Asif Salim’s “Notice to Inmate of Transfer to a Communications Management Unit,” which informs a person why they are being transferred to a CMU. He said he was given the notice weeks after he’d already been transferred to the CMU. The BOP never provided any evidence for the claims they made and Salim vehemently denies the allegations against him in the document. Provided by Salim.

. If they drifted into a different language, the call would be immediately cut. On at least one occasion, Salim said, BOP staff deleted emails containing the Arabic word “inshallah,” an extremely common phrase amongst all Arabic-speaking and Muslim people, meaning “God willing.”

In May, Salim convened with civil rights advocates at Atlanta’s Masjid Maryam, an Islamic center where he is a member. As part of a series of panels organized by the Coalition of Civil Freedoms, speakers encouraged the community to support Muslim political prisoners and remain vigilant against law enforcement incursions. They drew a line between post-9/11 surveillance and more recent efforts to target students protesting what many scholars are calling a genocide of Palestinians in Gaza by Israel, often by concocting supposed ties to Hamas, which the U.S. deems a “foreign terrorist organization.” The group explained that these tactics have landed politically active Muslims in prison—and from there, into CMUs—and that knowing how to avoid them is crucial to advocacy work.

Earlier this year, The Intercept reported that DHS was working on college campuses to fight what the agency referred to as “foreign malign influence.” Investigative reporter Ken Klippenstein reported that Congress has pressured the FBI to use informants in their monitoring of anti-war protests on campuses, mirroring tactics used after 9/11 to target and often entrap protesters, and particularly Muslim students.

The similarities between today’s environment and the post-9/11 era have been clear to Jayyousi, who said she’s been mistrustful of the federal government since her father’s arrest.

“You can’t talk about where you’re from. You can’t talk about what you support or what your religion is, or your background, your cultures, because it’s too dangerous,” she said.

At the Atlanta events, speakers encouraged parents to talk to their kids about how to safely protest war and advocate for Palestine without falling prey to informants or FBI officials looking to connect young people to U.S.-designated foreign terrorist groups. The masjid was filled with people after Friday prayers who listened intently and laughed at the panelists’ jokes about how Muslims are often too friendly to police and FBI officers: “Don’t invite them in,” one panelist joked. “Don’t offer them chai or laddoos.”

Asif Salim speaks on a panel in an Atlanta mosque with leadership from the civil rights group the Coalition for Civil Freedoms, as well as FBI whistleblower Terry Albury. (Photo: Nausheen Husain)

Salim has firsthand experience with law enforcement’s history of targeting students.

While attending the Ohio State University from 1998 to 2005, Salim became aware that the FBI was surveilling him after he participated in campus events around the time of then-Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon’s visit to the al-Aqsa mosque compound in East Jerusalem, which drew global backlash. As part of the school’s Muslim Students Association, Salim said he and other MSA members had set up tables on campus to talk to people about Islam, which, due to the timing, other students interpreted as part of the political protests. After the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, Salim said FBI agents began to visit his home.

Salim now has four kids, aged 10 to 16, and he said he tries to frame what happened to him as a part of a much longer historical thread. On the Atlanta panels, he compared the relationship between U.S. authorities and pro-Palestinian protestors to the one between Pharaoh and Moses—or Fir’aun and Musa in the Qur’an.

“Fir’aun said about Musa, he is trying to cause mischief and corruption on Earth when indeed, Fir’aun himself was actually Mr. Corruption,” said Salim. “That was then, and nothing has changed. They still paint us as the corrupters and mischief-makers, when in fact, they are the corrupters and mischief-makers.”