The International Initiative for the Promotion of Political Economy (IIPPE) holds a conference every year. It brings together radical and Marxist economists to discuss the latest theories of and developments in capitalism in sessions where many papers are presented. I have reported on previous conferences in this blog. This year’s conference took place in Istanbul, Turkey and the theme was: The Changing World Economy and Today’s Imperialism. I participated online by zoom in some sessions and also obtained papers from participants at the conference.

There were two plenary sessions on the main theme of the conference led by Trevor Ngwane of the University of Johannesburg, South Africa and Utsa Patnaik of Jawaharial Nehru University, India. I was only able to get second hand snippets of these plenaries, but as far as I can tell, Professor Ngwane was keen to tell his audience that socialists should not rely on the BRICS (or BRICS+ including new entrants, Iran, Saudi Arabia and soon Turkey) and its expanding institutions to resist the hegemony of the imperialist bloc led by the U.S.

The countries of the BRICS+ were just as capitalist and imperialist as the imperialist bloc of the Global North, argued Ngawani. They and their governments would exploit the poor just as much. Indeed, the most important economy in the BRICs+, China was capitalist and imperialist in its relations with the periphery. The BRICs countries could be characterised as ‘sub-imperialist’ (exploited by the imperialist bloc but exploiting others further down the ladder). The only force for change would come ‘from below’ from the working class in these countries, not from the likes of Xi in China, Modi in India, Ramaphosa in South Africe, Lula in Brazil, MbS in Saudi Arabia or the mullahs in Iran.

In my view, there is a lot of truth in Ngwane’s conclusion—we cannot expect these BRICS governments to transform the world despite their relative resistance to the U.S. imperialist bloc. On the other hand, Ngwane’s characterisation of China as imperialist, let alone capitalist, and all the BRICS as ‘sub-imperialist’ ,does not work for me. I shall return to those issues later in this post.

Utsa Patnaik is a famous Marxist Indian economist (along with her husband Prabhat). They developed the ‘drain theory’ of exploitation: that India’s revenues in the 19th century were drained to provide profits for Britain’s world hegemonic rise.

Indeed, recently, Kabeer Bora of the University of Utah made a novel attempt to measure the transfer of value appropriated by Britain from its ‘jewel in the crown’ colony India during the 19th century. Bora reckoned that this transfer of surplus value was invaluable for the success of the British economy. In his analysis, he relied on Marx’s law of the falling rate of profit, namely that as the rate of profit fell domestically, British capital counteracted that with increased profits drained from India. Bora measured the drain of value from India to Britain using the ratio of the India’s nominal exports to nominal imports to and from the UK. He found that an increase in this colonial ‘drain’ of 1% increases the rate of profit of Britain by around 9 percentage points. So not only did colonialism help Britain but it was particularly the drain of resources from India that did so.

Indeed, recently, Kabeer Bora of the University of Utah made a novel attempt to measure the transfer of value appropriated by Britain from its ‘jewel in the crown’ colony India during the 19th century. Bora reckoned that this transfer of surplus value was invaluable for the success of the British economy. In his analysis, he relied on Marx’s law of the falling rate of profit, namely that as the rate of profit fell domestically, British capital counteracted that with increased profits drained from India. Bora measured the drain of value from India to Britain using the ratio of the India’s nominal exports to nominal imports to and from the UK. He found that an increase in this colonial ‘drain’ of 1% increases the rate of profit of Britain by around 9 percentage points. So not only did colonialism help Britain but it was particularly the drain of resources from India that did so.

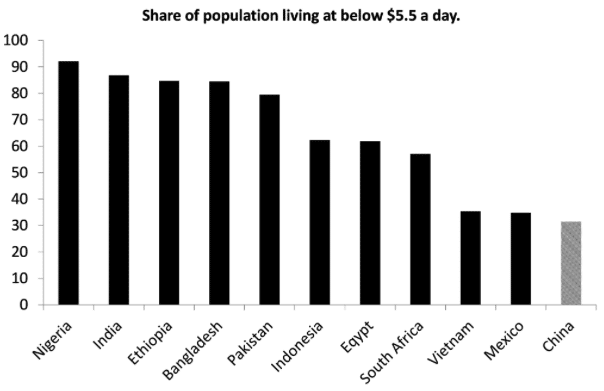

In her presentation, Patnaik concentrated on the failure to end poverty in the Global South. This failure was due to the exploitation of the poor countries by the Global North. She concentrated her remarks on the terrible levels of poverty based on measures of calorific intake. But she was also concerned to argue against the claim of China that it had got 800m Chinese out of poverty. That’s because China’s level of nutritional intake was also very low. On that criterion, China was really just as full of people in poverty as in India. And that’s because China was just as capitalist.

This argument was refuted from the floor: as China’s criteria for the poverty level is based on incomes and other categories of ‘well-being’ (food, clothing, education, medical support and safe housing). On those measures, China had way less poor people than India. Indeed, China’s poverty definitions more than match those of the World Bank and even the World Bank recognised China’s reduction in the number of those below the World Bank ‘higher threshold’ poverty level.

More disappointing was Patnaik’s proposed policy solutions for poverty in India and the global South. Following Keynes (not Marx), she reckoned governments needed to spend more money and run deficits to spend on alleviating poverty. Patnaik seemed to reject the ‘Chinese model’ and yet her own policy was unlikely to reduce poverty in India given the nature of the Modi government.

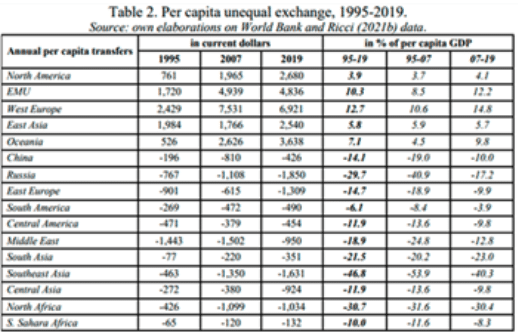

This brings me back to the question of whether China is capitalist and/or imperialist. I have discussed this at length in many posts on my blog and in papers and books. So I won’t go over the issue again here. Suffice it now to present some evidence against the idea that China is imperialist, or even ‘sub-imperialist’ ie it is exploited by the imperialist bloc, but at the same time exploits countries poorer than it (Africa?). Mino Carchedi and I have presented evidence on value transfers that show that China has made large transfers in value through trade and investment to the imperialist bloc.

Also Andrea Ricci of the University of Urbino, Italy has in the past shown a similar result. See this table of value transfers through unequal exchange in trade.

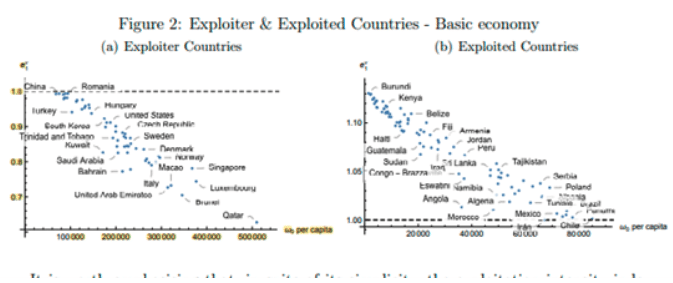

Robert Veneziani et al from the LSE, London also developed an ‘exploitation index’ for countries which showed that “all of the OECD countries are in the core, with exploitation intensity index well below 1 (ie less exploited than exploiting); while nearly all of the African countries are exploited, including the twenty most exploied”. The study put China on the cusp between exploited and exploiting.

So on all these measures of ‘imperialist exploitation’, China does not fit the bill, as least economically.

The great hope of the 1990s, as promoted by mainstream development economics was that Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (BRICS) would soon join the rich league by the 21st century. That has proven to be a mirage. These countries remain also-rans and are still subordinated and exploited by the imperialist core. There are no middle-rank economies, halfway between, which could be considered as ‘sub-imperialist’. And that includes China.

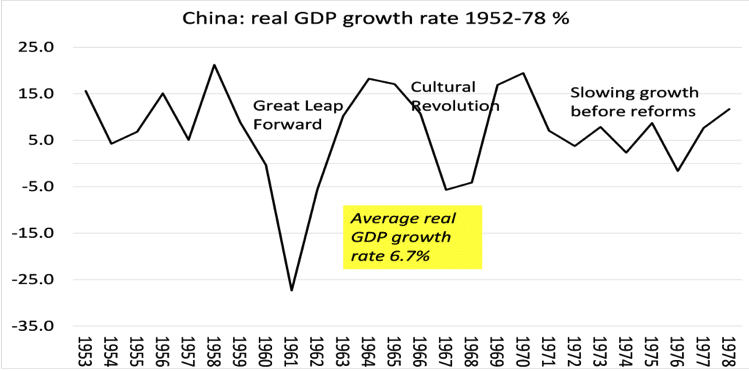

Talking of China, there were several sessions on China organised by the IIPPE China working group. The sessions were recorded and are available to view on the IIPPE China You tube channel. The sessions covered China’s development model, its high investment in EVs and solar, and on the likelihood that China would ‘catch up’ with the U.S. In a workshop session, I and others presented short papers. Mine aimed at showing, contrary to the conventional wisdom of the West, that Chinese economic growth before Deng reforms in 1978 was very strong, based on public ownership of the finance sector and the large companies, land reform for the peasantry and above all, national planning. There were only two periods of decline (the disastrous Great Leap forward of 1958-61 and the so-called ‘cultural revolution of the late 1960s).

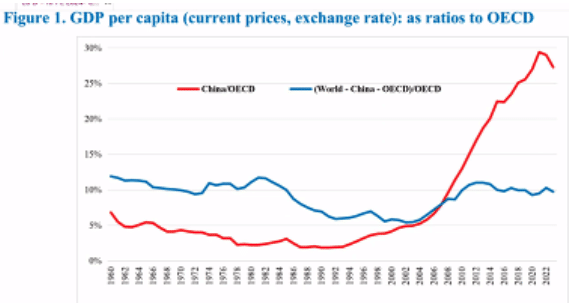

In his contribution, Professor Dic Lo of SOAS London made some telling points on the Chinese development model. And in a separate session, Dic Lo (China, the U.S. and the Global South) referred to the recent World Bank report outlining the necessary conditions for economies in the Global South to break out of what has been called the ‘middle-income trap’ and instead reach the living standards of the Global North. The World Bank calls these conditions, the ‘three Is’: investment, infusion (taking in new technologies from other countries) and innovation (developing new technologies themselves). Dic Lo reckoned if there was one country that could apply these conditions successfully it was China. Only China was ‘closing the gap’ with the imperialist North, if still a long way behind.

Indeed that is what frightens the U.S.—that it could eventually lose its hegemonic status in the world.

In a recent post, I discussed the World Bank report in detail. The report totally ignores the Chinese development model, preferring to put its hopes of ‘catching up’ in the relatively small capitalist market economies of Korea, Poland and Chile—just a tiny proportion of the world’s people and production compared to China. Even in these economies, there is a fundamental obstacle to achieve high income status as an important new book by Aldalmir Marquetti and colleagues explained.

What is that fundamental obstacle? Here is how Adalmir Marquetti put it:

it’s the falling profit rate that is the major determinant of decline in capital accumulation and investment. The problem is the profit rate approximates towards the level of the United States much faster than labor productivity. Essentially, the middle-income trap is a “profit rate trap”.

The problem for the Global South economies is that, as long as capitalism and the law of value remains dominant in their economies, there will be a contradiction between raising productivity and sustaining profitability: trying to raise the former leads to a fall in the latter and thus eventually limits growth.

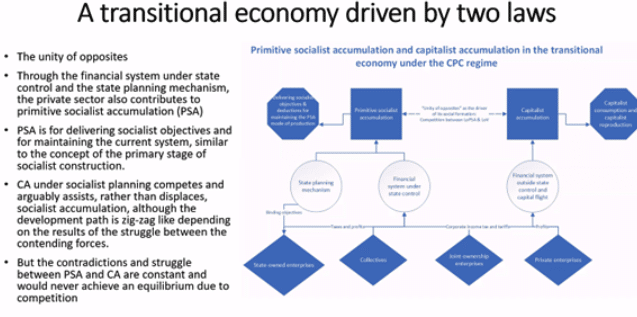

In another China session at IIPPE, this contradiction was well expressed by Sam Kee-Cheng of the University of Macau in her paper (Primitive socialist accumulation as contender development). Sam Kee-Cheng argued that China is a ‘transitional economy’ where the contradiction lies between an economy partly driven by capitalist accumulation for profit and partly by what Soviet economist Yevgeni Preobrazhensky called ‘primitive socialist accumulation’ which aims through planned investment to meet social objectives without the market.

Which will triumph: socialist accumulation or capitalist accumulation in China? If the latter, then Sam-Kee argued that China will not progress to high income status and will end up like Japan’s development model which came to a standstill once Japan ended its independent industrial strategy and bowed to U.S. dominance.

Sergio Camara from the University of Mexico (UAM) raised a similar argument in his paper (Is China breaking with neoliberal dynamics?). Camara argued that China’s state-led economy was capable of meeting its targets for ‘catching up’ but much, he thought, depended on building cooperation with other Global South economies like the BRICS+. Otherwise , the world economy would slip into “a bipolar world with a hegemonic vacuum generating real dangers for the future”.

There were several other papers that showed the strides that China was making with its development model in EVs, autos in general (Fanqi Lin, A case study of China’s NEV industry). So successful has China been in these important sectors that, as one paper pointed out (Tomas Costa, FDI in China 2013-23), despite the efforts of the U.S. and other Western governments to persuade or force Western investment to leave China, inward FDI remains high.

But there were other papers that showed the risk of failure due to the crises that the capitalist sector in China could get into. The most obvious was the collapse of the real estate sector and private developers leaving a huge debt burden on corporations and local governments (Alicia Giron). Adopting the Western model for urbanisation and housing in the 1990s to build homes for sale to owner occupiers, financed by mortgages and bond debt, turned for the worst—just as it did in the West in the 2007-8 real estate meltdown. Giron argued that, while China would avoid ‘a Minsky moment’ ie a financial crash that the West suffered in 2008, it showed the dangers of ‘financialisation’ in the Chinese economy.

In this context, Zhenzhen Zhang produced an interesting piece of empirical work that showed a high correlation between investment in productive sectors and growth. Increased investment in unproductuve financial and real estate sectors over productive sectors had reduced China’s growth potential after 2008. And that is why the CPC leadership are now emphasising ‘quality’ productive investment from hereon.

Given the theme of this year’s IIPPE (ie imperialism and the world economy), it meant that other important subjects for Marxist political economy did not get much of an airing. There were sessions on value theory and on the circulation of money capital (Takashi Satoh). And there were several papers presented on global warming and the rift between capitalist expansion and nature (Maria Pempetzoglou and Paraskevi Tsinaslanidou). There was also a paper by Joao Alcobia on the European Monetary Union which showed that the single currency had mainly helped the core of Europe (France, Germany) at the expense of the weaker southern member states. This is something I had noted some years ago in a paper.

But overall, the theme of the conference, at least to me, centred around whether the countries of the Global South could escape the grip of imperialism and start to ‘catch up’. Was that to be achieved by relying on the emerging and disparate coalition of BRICS+ governments or will it depend more on breaking with capitalism in each country and developing a transitional model of accumulation not based on the law of value?

At the conference, clearly many hoped and supported the former direction based around BRICs+. Indeed, Andrea Ricci made a presentation on the political implications of unequal exchange (ie imperialist exploitation) and the need to find a common agenda among Global South countries. My view is that Global South cooperation will only work in breaking the grip of imperialism when there is social and economic change within the major countries of Global South (and also in the imperialist core of the Global North).