This year marks the fortieth anniversary of the Vaal Uprising in South Africa. Throughout 1984, rent increases in Black townships were met with fierce opposition from residents. The increases came amid a deepening capitalist economic recession. All the factors converged and South Africa was rapidly becoming ungovernable. Apartheid colonialism was in crisis.

During the 1980s, the very foundation of South African white minority rule was crumbling due to a united people’s offensive that involved the escalation of armed struggle on a mass scale. There were many signs that the objective and subjective conditions which made possible a major revolutionary breakthrough were beginning to mature. The ruling class was finding it more and more difficult to continue to rule in the old way and the people were completely rejecting the rule of race domination and class exploitation in all their manifestations.

There was mass protest in other townships, but the uprisings in the Vaal Triangle marked the growth of mass-based organizations throughout the country and definitively put mass rejection of apartheid colonial rule high on the liberation agenda. The special significance of the 1980s upsurge lies in the fact that, for the first time, the retaliatory violence of the people had become a permanent feature of protracted rolling mass actions, distinct from the occasional occurrence that characterized the 1976 Soweto revolts.

In 1978, the Vaal Triangle Community Council (VTCC) introduced its economic rentals policy. Costs of housing provision, municipal services, and administration were to be covered by rents, which rose dramatically.1 The parliamentary victory of Afrikaner nationalism in 1948 signified a reversal of the postwar trend toward decolonialization in Asia and Africa. In a program of racial totalitarianism, the new regime merged the old colonial autocracy with industrial capitalism. A series of discriminatory laws completed the segregation of Africans, Coloured, and Indians, reducing them to staggering levels of subordination and consolidating the whites into one power.2 Because of the tremendous economic and political power that they possessed, monopolies exercised undue and dangerous influence over governments and government policies. Though they were fond of talking about democracy and democratic institutions, these actually meant the rule of the minority, the rich, and its exercise of power over the Black majority through the bourgeois state—the police force, the army, and the legal system. Even in countries where the people have voting rights, the monopolies always have the machinery of the capitalist state at their disposal. The people may have the right to vote for the representative institutions—parliament, provincial institutions, the municipalities—but this does not mean that people have access to these institutions, which are always hemmed in by economic barriers.3

The passing of the Black Local Authorities (BLA) Act 102 of 1982, part of a set of bills popularly known as the “Koornhof Bills,” further decentralized power by giving town councils increased authority. Under the jurisdiction of the Orange Vaal Development Board, four councils were identified to become BLA, namely the Vaal Triangle, Evaton, and Kroonstad and Bethlehem in the Free State. Another eighty-four townships were identified across the country to follow suit in 1984. The Vaal Triangle was the first area to hold elections on November 27, 1983, with 14 percent of registered voters (or 9 percent of the adult population) voting the Lekoa Town Council (LTC) into power. Elections for the Evaton Town Council were held separately. The Lekoa Town Council included thirty-nine seats and represented six townships: Sebokeng, Boipatong, Bophelong, Sharpeville, Zamdela, and Referengkgotso. Both town councils came into being on January 1, 1984. The low turnout was a clear indication of dissatisfaction with the new political framework and testimony to councilors’ lack of legitimacy.4 The Vaal Civic Association (VCA), a United Democratic Front (UDF) affiliate, coordinated opposition to the rent increase. Before the rent hikes, the major campaign, launched in October 1983, was opposition to the November BLA elections. When rent increases were announced in July, the VCA organized an anti-rent campaign.5 By giving the new BLA powers to increase rents, the seeds of their destruction were sown. Despite election promises, councilors increased rents and service charges while doing nothing to improve living conditions. Township uprisings began in Tumahole in July 1984, but it was the uprising in the Vaal Triangle in September 1984 that signaled the end of the BLAs throughout the country.6

The basis for the rent boycott was put aptly by the veteran Trade Unionist and Communist Party stalwart Dan Tloome, when he wrote thirty years before the Vaal Uprising that it was absurd and unreasonable for citizens to pay economic rentals on subeconomic houses. He called on the regime to pass legislation to raise the minimum wage for all workers to ensure that people could afford economic rentals. Of all the outstanding issues that had provoked intense protest and resentment among the African people, the question of rent increases stood out as the most callous and as a direct assault on the ever-worsening economic position of the lowest income group of the community—the Africans.7

In the January 8, 1984, statement observing the seventy-second anniversary of the African National Congress (ANC), the then ANC President Cde Oliver Reginald Tambo outlined the program for the enfeebling of apartheid institutions:

You are aware that the apartheid regime maintains an extensive administrative system through which it directs our lives. This system includes organs of central and provincial government, the army and the police, the judiciary, the Bantustans administrations, the community councils, the local management and local affairs committees. It is these institutions of apartheid power that we must attack and demolish, as part of the struggle to put an end to racist minority rule in our country. Needless to say, as strategists, we must select for attack those parts of the enemy administrative system which we have the power to destroy, as a result of our united and determined offensive. We must hit the enemy where it is weakest.8

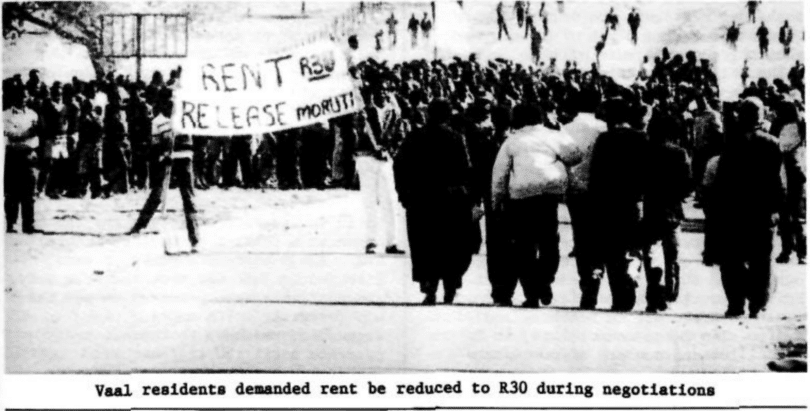

Announcement of the rent increases was delayed so that individual councilors could break the news to their wards first. However, this did not happen in most cases and when a general announcement of the increases was made in late July, residents and local organizations responded with fierce disapproval.9 In August 1984, thousands protested the rent increases. They decided that they would not pay September rent until the increases were dropped and called for the resignation of all councilors. On Sunday, September 2, 1984, residents at three mass meetings in the Vaal resolved to stay home from work and school, and instead to march peacefully to administration board offices the following day.10 The council ignored all demands for a suspension of the rent increases. Its only response was to call a meeting with Vaal church leaders, warning that their site permits would be withdrawn if they continued to allow churches to be used for political meetings. On September 3, 1984, a stay-away and peaceful protest march against rent hikes in the Vaal turned into a bloody confrontation between residents and police. In the ensuing conflict, four councilors were killed. Conflict spread throughout the Vaal Triangle and sixty-six people died in the first week. The Vaal massacre was the first (since the 1976 Students Upsurge) in a series of massacres committed by the apartheid security force: in Langa on March 21, 1985; Mamelodi in November 1985; and Alexandra in January 1986.11

Before September 1984, the Department of Cooperation and Development considered Black local government in the Vaal to be the most successful in the country. Vaal local authorities ran at a profit. Throughout its existence, the VTCC managed to balance its books and subsidized Orange Vaal Administration Board projects in the Free State and QwaQwa. Its economic rentals policy made this possible and the seven years prior to 1984 saw dramatic increases in Vaal rents. In 1977, average Vaal rents were R11.87 per month; by the start of 1984 they were R62.56—more than R10 higher than anywhere else in the country. At a meeting on June 29, 1984, the LTC decided to increase monthly rents by R5.90 for board houses and R5.50 for private houses. The LTC maintained that Vaal residents were the best paid in the country and could afford higher rents. This myth was dispelled by the 1985 Bureau of Market Research report, which showed that average annual Black per capita income in the Vaal Triangle were substantially below the national metropolitan average of R l,112.79 versus R l,366.24 in 1983; Rl,159.82 versus Rl,396.48 in 1985. While the real increase in Black incomes between 1980 and 1985 was 17 percent, rent increased by 56 percent.12

September 1984 was a milestone in a year that had seen a ferment of resistance. An alignment of forces the regime had not faced for a long time were involved in the resistance in the Vaal Triangle and other townships since 1984. There had been stubborn resistance all along, not only since the first quarter of 1984, but since the turn of the decade. But the resistance that was launched by the people of the Vaal Triangle was salient for the social forces it brought into the struggle. From the onset, the people struck with their iron fist: the working class. The totality of the forces deployed to strike a decisive blow for people’s demands were trade unions and political, civic, youth, and student organizations. These represented a total mobilization of township forces.13 It was the active involvement of the working class that set this chapter of resistance apart from the popular resistance that had taken place since the beginning of the action-packed ‘80s. The participation of the workers heralded the advent of a new qualitative degree in the resistance.14

Fighting in the townships, labor unrest, classroom revolts, rent strikes, consumer boycotts, worker stayaways, and guerilla warfare had become familiar features of South Africa’s political landscape since 1976. But with the UDF in 1983, radical opposition assumed a more organized form. Resistance became increasingly effective because of the UDF’s capacity to provide a national political and ideological center. However, the township revolt was not caused by strategies formulated and implemented by UDF national leadership. With the exception of key national campaigns (such as the BLA election boycotts of 1983 and 1984, and the anti-tricameral parliament campaigns), the driving force of resistance came from below, as communities responded to their terrible living conditions. Since early 1984, literally hundreds of community organizations allied to the UDF sprung up around the country. And although the major trade union federations had not formally affiliated, they developed strong working relationships with the UDF over the years.15

The complex patchwork of local community organizations that became the organizational foundation of the UDF developed out of local urban struggles that took place before and after the formation of the front. At first, these struggles involved minor conflicts between communities and local authorities over issues such as transport, housing, rent, and service charges. But the authorities’ coercive responses and refusal to make concessions transformed the local urban struggles into campaigns with a national political focus. This transformation was not the simple outcome of local “reformist” organizations affiliating to the front’s national class-based program. Rather, these struggles contained an increasingly powerful national challenge to the state’s racial and class character that the front expressed instead of directly instigating.16

Lacking popular support, the regime was forced to resort more and more to the use of force, but the more it did so, the more popular resistance grew. The points of conflict, both internally and externally, multiplied. The spiral of violence turned inexorably toward catastrophe. In October 1984, seven thousand troops invaded the township of Sebokeng. In November 1984, the Congress of South African Students (COSAS) initiated the largest stayaway in thirty-five years occurring in the Transvaal to support the demand for the withdrawal of the army police from the township, resignation of community councilors, the release of detainees and political prisoners, and stops to rent and bus fare increases.17 The response to the stayaway call was tremendous and the action a historic one. Radio Freedom, the voice of the ANC, broadcasting on November 9, 1984, called it a “resounding success…a victory scored in the face of a massive police and army presence in the townships.” The UDF backed a call by some unions to make Christmas 1984 a “Black Christmas” to mourn for those killed, injured, or detained as a result of the township uprisings.18

The success of the stayaway of 1984 demonstrated activists’ growing experience of the process of political organization and mobilization. In contrast to the less successful spate of stayaway strikes in 1976, its key features were the participation of organized labor and the effective linkage of community, student, and worker organizations. It marked a new phase in the history of protest against apartheid: the beginning of united action among organized labor, students, and community organizations. In November 1984, COSAS activists were especially intent to support the stayaway through its mobilization of workers.19 The stayaway experience gave the hundreds of thousands who went on strike a feeling of great confidence in their collective strength. It sent a message to all our working people that political and economic demands could not be separated. It put the class and national dimensions of our revolution into a proper perspective. It exposed those meddlers who were trying to stop the trade union movement from playing a part in the national liberation struggle. A crisis of unprecedented scale had emerged in South Africa. At no other time in our history has the popular uprising of masses rendered the apartheid system so unworkable and the whole country ungovernable, and at no other time has the apartheid power revealed such bankruptcy of both ability and strategy to survive. This precipitated the clarion call made by Cde President Tambo to our people on January 8, 1985, to render South Africa ungovernable and make apartheid unworkable.

Eight people in the Vaal were sentenced to death. The Sharpeville Six—Mojalefa Sefatsa, Oupa Diniso, Duma Khumalo, Francis Mokhesi, Reid Mokoena, and Thereza Ramashamola—were sentenced to death for killing a councilor in Sharpeville. Daniel Maleke and Josiah Tsawane were sentenced to death for killing a policeman in Sebokeng. On June 11, 1985, twenty-two antiapartheid activists, including leaders of the UDF and VCA, were charged with treason, murder, terrorism, and subversion in what was known as Delmas Treason Trial.

The brutal massacres of our people did not dampen the people’s determination to resist. If anything, racist violence had educated and prepared them for higher forms of struggle. Revolution is creative work through daily confrontation with the enemy. The advanced representatives of the people had acclimatized themselves, not as a result of theoretical reasoning, but under the impact of the course of events, at an appreciation of the new and higher tasks of the struggle. Because there is no day when oppression postpones itself and does not affect the masses, there was no way that the struggle could be postponed. These new outbreaks of revolts by workers and students were constantly accompanied by unorganized and sporadic street fighting and other acts of violent resistance on a nation-wide scale. Unlike the lull that followed the 1960 Sharpeville massacre, the outbreak of the 1984 Vaal Uprisings was followed by prolonged and widespread civil uprisings. The Vaal region experienced more massacres by the apartheid colonial killing machineries than any other region in South Africa. Other massacres in the Vaal include: the Sharpeville Massacre on March 21, 1960, Sebokeng Massacre on March 26, 1990, Night Vigil Massacre in Evaton on January 12, 1991, and Boipatong Massacre on June 17, 1992.

The history of the struggle of the Vaal Triangle is written in the blood of our martyrs.

Notes

1. Karen Jochelson, “Rent Boycotts: Local Authorities on their Knees,” Work in Progress 44 (September/October 1986): 14.

2. Ray Simons and Jack Simons, Class and Colour in South Africa 1850–1950 (International Defence and Aid Fund, 1983), 624.

3. Jalang Kwena, “Imperialism—The Last Stage of Capitalism,” African Communist 6 (1961): 59.

4. Franziska Rueedi, The Vaal Uprising of 1984 and the Struggle for Freedom in South Africa (James Currey, 2021).

5. Jochelson, “Rent Boycotts,” 17.

6. Lehlohonolo Kennedy Mahlatsi, “40th Anniversary of the UDF,” Re Betla Tsela 45 (August 2023): 8.

7. Dan Tloome, “Rent Increases,” Liberation 9 (1954): 18, 21.

8. ANC President Oliver Tambo, “Statement of the National Executive Committee on the Occasion of the 72th Anniversary of the ANC,” January 8, 1984, www.anc1912.org.za, accessed September 25, 2024.

9. Jochelson, “Rent Boycotts,” 17.

10. Aziz Pahad, “Making Apartheid Unworkable: Mass Resistance,” Sechaba (November 1984): 8.

11. United Democratic Front, “3 Years of United Action,” Isizwe 1, no. 3 (November 1986): 47.

12. Jochelson, “Rent Boycotts,” 16.

13. Cassius Mandla, “The Moment of Revolution Is Now—Or Never in Our Lifetime,” Sechaba (November 1985): 23.

14. Mandla, “The Moment of Revolution Is Now,” 24.

15. Mark Shilling, “The United Democratic Front and Township Revolt,” Work in Progress 49 (September 1987): 26.

16. Shilling, “The United Democratic Front and Township Revolt,” 27.

17. United Democratic Front, “3 Years of United Action,” 47.

18. Jean Middleton, “Unity of Democratic Forces: The Transvaal Stayaway,” Sechaba, (February 1985): 15; Lehlohonolo Kennedy Mahlatsi, “Looking Back 38 Years, in Retrospect of the Vaal Uprisings,” Independent Online, September 5, 2022.

19. Graham Howe, “The Stayaway Strikes of 1984,” Indicator South Africa 2, no. 4 (January 1985): 1.