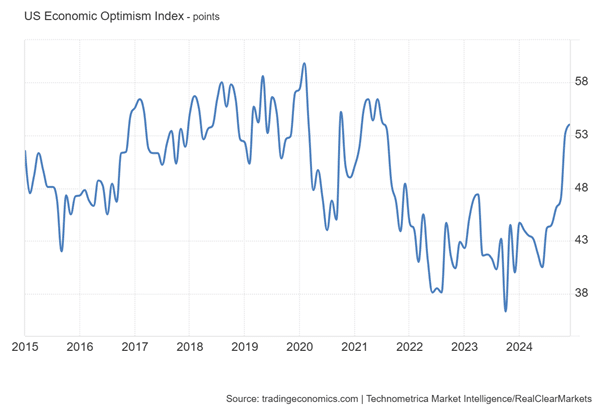

Recently, there has been a spate of articles and commentary about ‘U.S. exceptionalism’, namely that the U.S. economy is bounding forward in terms of economic growth, hi-tech investment and productivity, leaving the rest of the world behind. And so no wonder that the U.S. dollar is riding high and its stock markets are booming. This success is put down to less regulation, an entrepreneurial spirit, lower taxes on investment etc—in other words, none of this government interference that Europe, Japan and other advanced capitalist economies suffer. Optimism reigns about America’s success, even it seems among the wider public and not just in stock markets. The RealClearMarkets/TIPP Economic Optimism Index in the U.S. has risen to its highest since August 2021, if still below the pre-pandemic years.

But this story of boom is misleading. Yes, the U.S. economy is doing better than Europe or Japan. But is it doing better historically? Take the recent piece in the UK’s Financial Times lauding the U.S. performance relative to Europe entitled “why America’s economy is soaring ahead of its rivals”. The authors go on: “the U.S. is growing so much faster than any other advanced economy. Its GDP has expanded by 11.4 per cent since the end of 2019 and in its latest forecast, the IMF predicted U.S. growth at 2.8 per cent this year.” And:

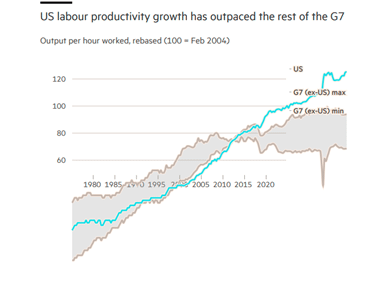

its growth record is rooted in faster productivity growth–a more enduring driver of economic performance….U.S. labour productivity has grown by 30 per cent since the 2008-09 financial crisis, more than three times the pace in the Eurozone and the UK. That productivity gap, visible for a decade, is reshaping the hierarchy of the global economy.

And more:

productivity growth the U.S. is rapidly outstripping almost all advanced economies, many of which are caught in a spiral of low growth, weakening living standards, strained public finances and impaired geopolitical influence.

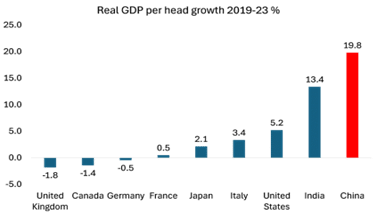

The problem with this narrative is that it is all relative. Note the title of article: why America’s economy is soaring—ahead of its rivals. The U.S. economy is soaring, wait… but only ahead of its rivals. Yes, compared to Europe and the rest of the advanced capitalist economies (of course, not compared to China or India), the U.S. is doing much better. But that’s because Europe, Japan, Canada are stagnating and even in outright recession. In historic terms, the U.S. economy is doing worse than in the 2010s and worse again compared to the 2000s.

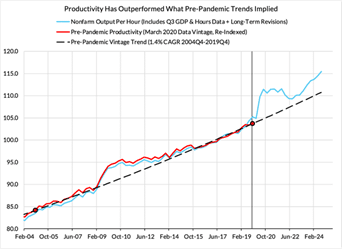

Take productivity growth. Here is the FT graph that suggests U.S. exceptionalism.

But if you look closely at the trajectory of the U.S. productivity growth line, you can see that from about 2010, productivity growth in the U.S. has been slowing. Its relative outperformance is entirely due the collapse of growth in the rest of the G7. As the FT article puts it: “Data from the Conference Board shows that, in the past few years, labour productivity has dropped relative to that of the U.S. in most advanced economies.” Yes, relative to the U.S., but labour productivity growth in the U.S. is slowing down too, if by not so much.

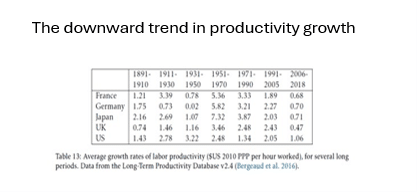

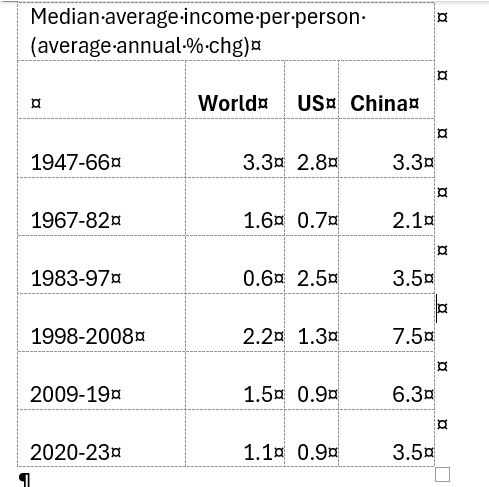

Indeed, if we go way back on the history of productivity growth, the real story is that capitalist economies are increasingly failing to expand the productive forces and raise the productivity of labour. You can see that from the table below. U.S. productivity growth from 2006-18 is much better than other major capitalist economies, but the rate is half what it was in the 1990s.

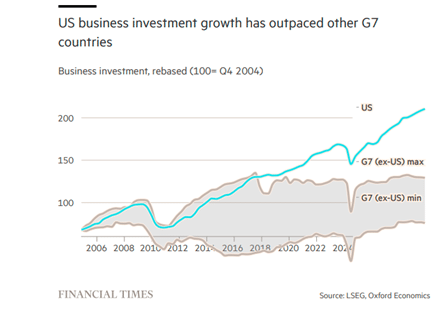

The same narrative applies to productive business investment. The FT shows a graph where U.S. business investment growth is outpacing other economies. But again, note that the trajectory of U.S. investment growth is also slowing: compare the current growth rate with that of the 2010s and even more with the 2000s. U.S. business investment is slowing over the long term, while in the rest of the G7, business investment is stagnating.

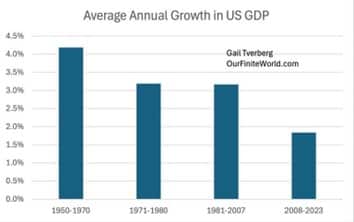

Let’s take another graph that shows the historic trend of economic growth in the U.S.

Average annual real GDP growth in the U.S. has declined from the 4% rate in the post-war ‘Golden Age’ to 3% a year before the Great Recession and under 2% in the period since then, in what I have called the Long Depression. And current consensus forecasts for U.S. growth in 2025 are just 1.9%. But that would still be the fastest of any G7 economy.

Moreover, we are measuring real GDP growth here. In recent years, much of the faster growth in the U.S. has been due to immigration, boosting the labour force and overall output. Growth in output per person has been much less, if still better than the rest of the G7 after the pandemic.

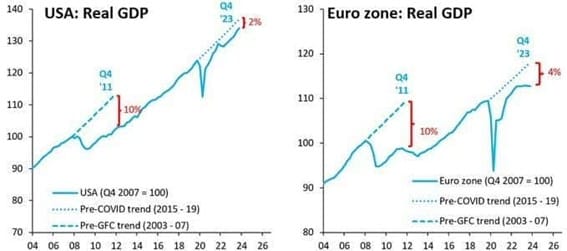

The graph below of trend growth for the U.S. versus Europe shows the story better. U.S. trend growth rates have been slipping in the 21st century; while Europe’s have been diving.

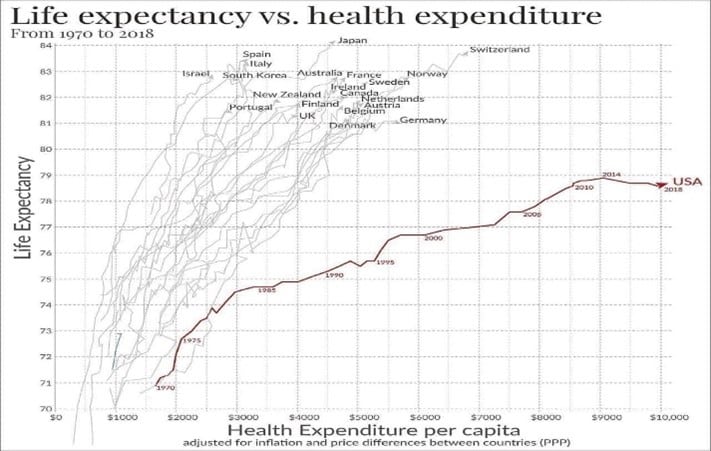

Moreover, the relatively better performance of the U.S. capitalist economy over the other advanced economies does not indicate whether average Americans are doing better. As the FT article admits: “For all its economic power, the U.S. has the largest income inequality in the G7, coupled with the lowest life expectancy and the highest housing costs, according to the OECD. Market competition is limited and millions of workers endure unstable employment conditions.” Hardly a recruitment poster for living in the U.S., even if stock market investors don’t care about that.

And if we are talking above relative growth in average income per person in the U.S., look at this table that I have compiled from the World Inequality Database. Average earners in the U.S. are seeing less and less progress (even relatively), particularly in the 21st century.

Nevertheless, the argument goes that a U.S. productivity boom is now under way, driven by the introduction of AI and other technology investment that the rest of the capitalist world (and China) cannot match. As Nathan Sheets, chief economist at Citigroup, says that, despite these efforts and China’s push to become an AI superpower, the U.S. is the “place where AI is happening, and will continue to be the place where AI happens”. And there are signs that U.S. productivity growth may be picking up—although note that the graph below is an estimate.

Maybe so, but the huge investment spending in AI has yet to be see real results across the whole economy that could reduce significantly jobs and so sustain a a large rise in productivity per worker. That could take decades.

Indeed, there is plenty of evidence that the AI boom could really just be a bubble—a huge rise in what Marx called fictitious capital, ie investment in the stocks of AI-related companies and the U.S. dollar that is way out of line with the reality of AI-realised profits and productive investment.

In the FT again, Ruchir Sharma, chair of Rockefeller International called the U.S. stock market boom “the mother of all bubbles”. Let me quote:

global investors are committing more capital to a single country than ever before in modern history. The U.S. stock market now floats above the rest. Relative prices are the highest since data began over a century ago and relative valuations are at a peak since data began half a century ago. As a result, the U.S. accounts for nearly 70 per cent of the leading global stock index, up from 30 per cent in the 1980s. And the dollar, by some measures, trades at a higher value than at any time since the developed world abandoned fixed exchange rates 50 years ago.

But “Awe of “American exceptionalism” in markets has now gone too far….Talk of bubbles in tech or AI, or in investment strategies focused on growth and momentum, obscures the mother of all bubbles in U.S. markets. Thoroughly dominating the mind space of global investors, America is over-owned, overvalued and overhyped to a degree never seen before. As with all bubbles, it is hard to know when this one will deflate, or what will trigger its decline.”

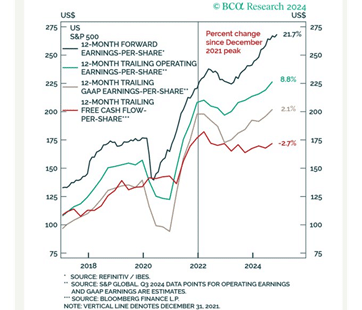

And this bubble is very narrowly supported. U.S. stock market drives world markets and just seven stocks drive U.S. stock market: the so-called Magnificent Seven. For the vast majority of U.S. companies, those outside the burgeoning energy sector, social media and tech, things are not so great. S&P 500 free cash flow per share hasn’t grown at all in three years (see the red line below). Forecasts of profit growth are wildly out of line with what is being realised.

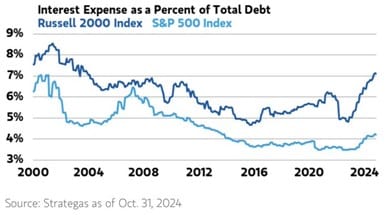

U.S. corporate debt to earnings remains near all-time highs and interest costs on this debt have not fallen much since the U.S. Fed decided to start cutting its policy rate.

The difference in the average cost of debt for the smaller Russell 2000 companies and the big S&P 500 companies recently more than doubled to about 300 basis points. With intermediate and long-term interest rates still backing up, it is not obvious that relief will come soon.

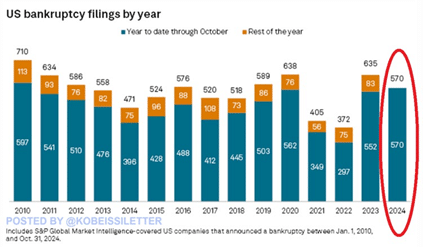

U.S. corporate bankruptcies in 2024 have surpassed 2020 pandemic levels. Bankruptcies are surging as if the U.S. economy was struggling.

In its recent Financial Stability Report, the Federal Reserve noted that “valuation pressures remained elevated. The ratio of equity prices to earnings moved up toward the high end of its historical range, and an estimate of the equity premium—the compensation for risk in equity markets—remained well below average.” It was concerned that “While balance sheets in the nonfinancial business and household sectors remained sound, a sharp downturn in economic activity would depress business earnings and household incomes and reduce the debt-servicing capacity of smaller, riskier businesses with already low ICrs as well as particularly financially stretched households.

There is no bust yet in the stock markets. But if a bust comes, with many companies struggling and debt burden rising, a financial crash could well ricochet into the ‘real economy’. And spillover globally.

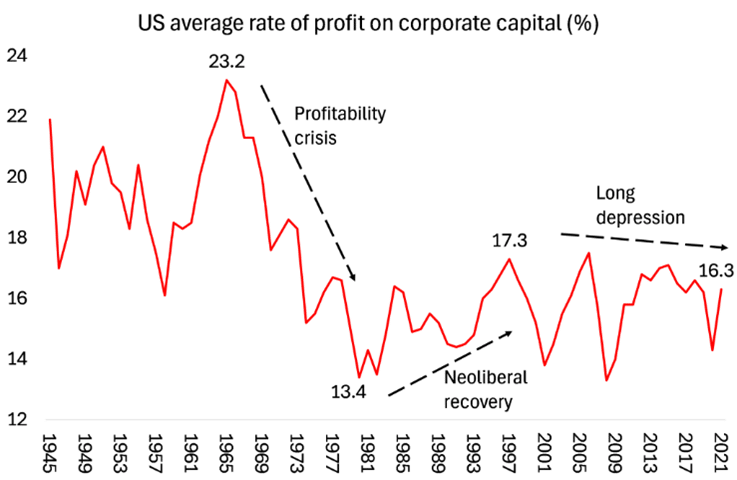

Productivity growth in the major economies has slowed across the board because productive investment growth dropped. And in capitalist economies, productive investment is driven by profitability. The neo-liberal attempt to raise profitability after the profitability crisis of the 1970s was only partially successful and came to an end as the new century began. The stagnation and ‘long depression’ of the 21st century is exhibited in rising private and public debt as governments and corporations try to overcome stagnant and low profitability by increasing borrowing.

That remains the Achilles heel of the U.S. exceptionalism. The story of U.S. exceptionalism is really a story of Europe’s collapse—and that’s another story.