Successfully fighting a wildfire requires more than people digging line or cutting fire breaks with chainsaws. It also involves people who call grazing lessees to tell them to evacuate their cows, provide food for firefighters in the field and map the resources that the firefighters need to protect. People filling all these positions were recently terminated on one national forest–a problem that spans forests across the West.

“We lost the whole suite of support,” a Forest Service fire management officer, who asked to remain anonymous for fear of retribution from their employer, told High Country News.

It is leaving us woefully unprepared for fire this summer.

Elon Musk’s so-called Department of Government Efficiency claimed that firefighters were exempt from its purge of at least 2,000 employees from the U.S. Forest Service along with 800 others from the Bureau of Land Management on Valentine’s Day and President’s Day weekend. “Hiring freeze exemptions exist for critical health and safety positions,” meaning wildland firefighters, U.S. Department of Agriculture spokesperson Audra Weeks told High Country News via email.

But public-land management employees say this is not the whole story, because it leaves out collateral-duty firefighter positions.

These are the employees whose primary job isn’t fire. Maybe they work on trail crews, or study soil, or communicate information with the public. But many of the people in these non-fire positions also train to earn and maintain certifications–colloquially called “red cards”–that qualify them for helping with wildfire fighting. “Collateral duty firefighters make up a significant portion of the wildland firefighting force,” the fire management officer said.

The scope of the problem became clear Thursday. More than 75% of the recently fired probationary employees nationwide had red cards, according to testimony provided by Frank Beum, a retired regional forester and board member of the National Association of Forest Service Retirees, during a Senate Agriculture subcommittee hearing. Beum said these collateral fire duty positions are the “backbone” of fire suppression and prescribed fire. Senator Michael Bennet (D-Co.) called the situation an “emergency.”

“Everyone keeps saying, ‘Well, we’re not firing firefighters,’” the fire management officer said.

But that’s not the truth either. It takes a village to fight fire.

Some of these crucial employees may, at least for now, be getting their jobs back. An independent federal board, the Merit Systems Protection Board, ordered the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which oversees the Forest Service, to temporarily reinstate almost 6,000 employees on March 5, because there were reasonable grounds to believe the terminations were illegal. “We have not had any direction/interpretation from anyone on the court decision,” the fire management officer told HCN on the evening of March 5.

But those positions may still not be safe, as the Trump administration has repeatedly called for massive workforce reductions in the federal government and is exploring other, potentially legal, options to do that. Furthermore, the temporary reinstatement is only for 45 days. Immediately after the order, current Forest Service employees said they were still in the dark as to what this means, while fired employees took to social media to say that they had yet to be offered their jobs back.

A Region 1 Forest Service employee in Montana who asked for anonymity to protect their job said that 30% of their district staff were terminated. Many of them had red cards or worked other fire support jobs without them. “In a busy season, we would definitely be leaning on those people that were terminated,” they said.

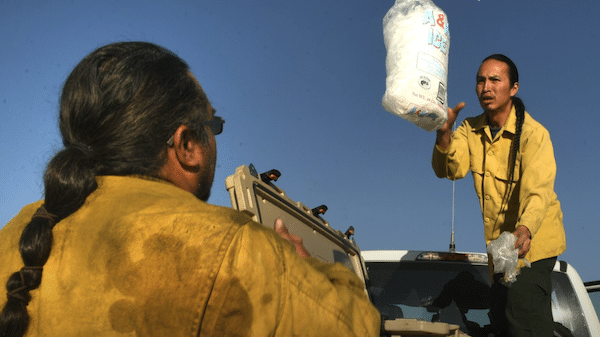

They could help with evacuations, post information at trailheads, shuttle people or supplies to a trailhead, or take stuff back and forth to the airport for helicopters to deliver to on-the-ground firefighters.

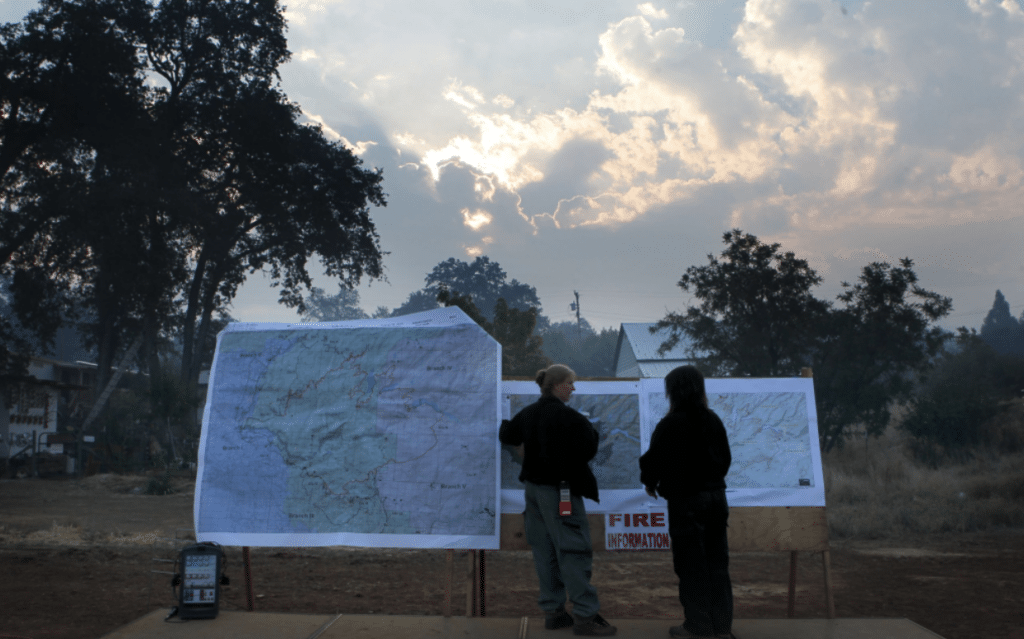

Firefighters check updated information after their morning meeting at base camp in Tuolumne City, California, in 2013 as the Rim Fire burns Stanislaus National Forest. (Photo: Michael Macor/The San Francisco Chronicle via Getty Images/ High Country News)

FEDERAL FIREFIGHTING ON PUBLIC LANDS in the U.S. works like this: Resources rotate as the fire season progresses regionally. For example, Western firefighters and support teams are currently being sent to the East Coast and Texas, where wildfires are burning. They’ll head to the Southwest in the spring, and then, in the late summer and fall, they’ll go to the Northwest. “Normally I’d have a couple (people) down in Texas right now helping out,” the fire management officer said.

But because they no longer have all those red-card-holding, collateral fire-duty workers, there aren’t enough people available to respond to a local fire if the primary firefighters are gone. “I don’t see us having the ability to help outside of our own forest nearly as much as we have in the past,” they said. During the Senate hearing on Thursday, Beum said 1,000 Forest Service employees–including many who worked on wildfire’s incident management and command teams, hand crews, operations, logistics and more–took the administration’s deferred resignation offer, further crippling the Forest Service’s ability to fight fire.

All of this could have a cascading effect this summer, if forests are forced to keep their primary firefighters close to home and larger fires in other regions are unable to summon the usual number of shared resources. Severely understaffed districts may also require employees to stay in the area to complete basic functions. “We might be spending more time cleaning toilets, building trails or whatever we need for the district that usually is done by those other people,” the Region 1 employee said.

If we have a busy fire season locally or nationally, we’re not going to have the support that we’re accustomed to.

Though snow is still on the ground in many parts of the West, the effects of federal directives are already being felt. The Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation in Washington rely on Bureau of Indian Affairs funding to employ tribal members as wildland firefighters. According to reporting by Stateline, Trump’s freeze on federal hiring “has halted the onboarding process for those staffers.”

The Bureau of Land Management’s fire resources are also being impacted by the mass layoffs. A BLM employee who works in fires and fuels planning, who asked to remain anonymous for fear of retribution, said most if not all the employees in BLM field units are red-carded and able to contribute to local fire response. It’s common for these employees to work as resource advisors, protecting species, cultural items and other natural resources from wildfire and fire-suppression activities.

The timing of the government chaos and uncertainty couldn’t be worse, the BLM employee said:

The disruption happening at this time of year is taking attention away from fire season preparation.

And a busy fire season is already stacking up. The National Interagency Fire Center’s Predictive Services has forecast above-normal temperatures for the Southwest and Great Basin starting this month, meaning these regions have an above-normal potential for wildfires. Meanwhile, above-average potential for wildfires in Alaska is expected to start in April, and come May, Southern California is predicted to have increased potential for wildfires, too.