Increasing militarization of the Pacific continues to cause tension inside and outside the region. In Hawai‘i, where the U.S. Navy’s Pacific fleet is stationed, Indigenous rights advocates have fought for decades against expansive military occupation and use of their lands and surrounding ocean.

One of them, Joy Enomoto, who lives on the island of O‘ahu, talks to Teuila Fuatai about that fight and the legacy of the U.S. military in Hawai‘i.

In the recent U.S. federal election, a bunch of Hawaiians voted for Trump.

I don’t think that’s because Trump represented our values and needs. It was more that a lot of folks here felt abandoned and overlooked by the U.S. under the Democratic Party. Many felt that our islands, away from the mainland, had been forgotten in the past few years.

But as Kānaka Maoli–Indigenous Hawaiians–I want us to understand that there is so much more to our relationship with the U.S. than who is president and what they promise us. We need to understand why the social, health, and environmental problems we experience will never be genuinely addressed by any U.S. politician or leader, especially someone like Trump. And why the U.S. is so invested in keeping us under its thumb.

Hawai‘i is valuable to the U.S. because its navy can fuel up here. We’re a launching pad into the Philippines and the wider Asia region. To the U.S., Hawai‘i is a giant, strategically significant military station.

When my partner and I moved from Maui to the island of O‘ahu, we found the presence of the military overwhelming. Every branch–army, navy, air force, marines, and the coastguard–has bases here. We constantly have army helicopters flying over the house, and at the airport, it’s normal to see B-52 bombers taking off for exercises.

Then, when the RIMPAC (Rim of the Pacific) military exercise takes place, things really ramp up.

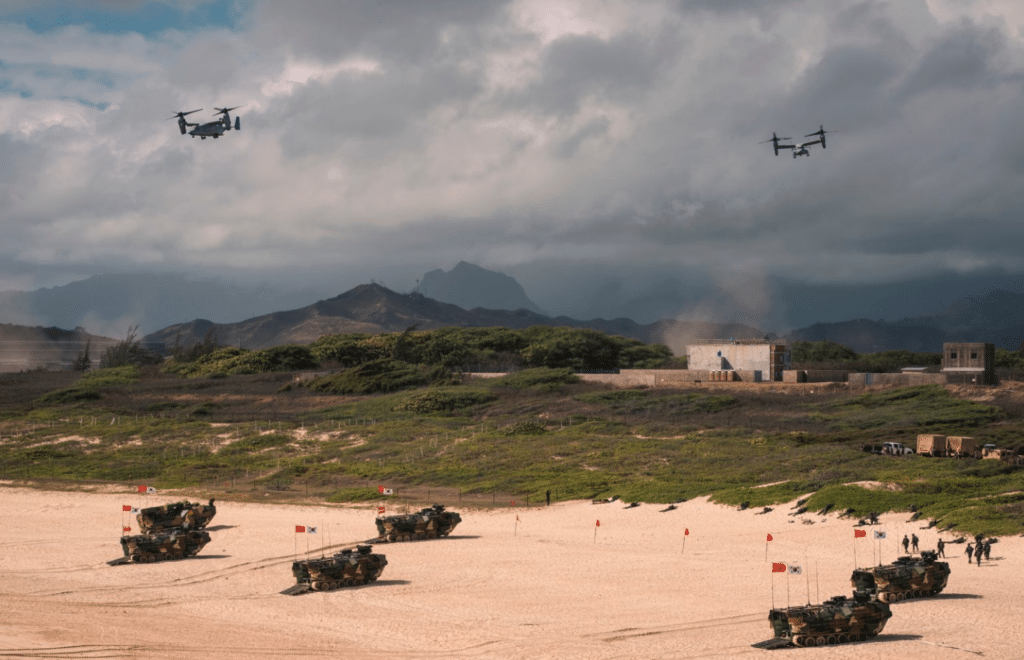

Military exercises carried out during RIMPAC 2024.

RIMPAC is massive. It’s the world’s biggest international maritime warfare exercise. Hosted by the U.S., it happens every two years and involves about 30 countries, including New Zealand. The exercises are performed on and around different islands in Hawai‘i.

The intensity of the military activity is bad enough. Last year, 40 ships, three submarines, and 150 aircraft were part of RIMPAC. In Honolulu, that resulted in about 25,000 soldiers coming into town.

But there’s also the impact on our local communities and families. At bars and strip clubs, the “Welcome RIMPAC” banners come out. An increase in military personnel always results in a rise in violent incidents in our islands. There’s a significant increase in domestic violence incidents, and a lot of the shootings here, as well as rape cases, are tied to former or current military personnel.

Beach landed exercise during RIMPAC 2024.

Of course, military activity also affects our environment and the animals that inhabit our islands.

In 2020, during our Covid restrictions, RIMPAC was canceled. Nothing was allowed to land in Hawai‘i, so the only exercises were at sea. We didn’t have any amphibious landings, and there was no coastal damage or noise from war exercises. As a result, turtles that used to nest along the coastlines of some of our islands returned.

The U.S. military is a significant polluter. In Hawai‘i, we see the impacts of that everywhere.

Take Pearl Harbour, for example. This was one of our critical, food-producing deep sea harbors in O‘ahu. It was particularly unique because you could catch deep sea fish close to the land. It also had around 20 fish ponds and was a place where sharks mated. For the local Kānaka Maoli, that harbor was our food basket. But it’s been heavily contaminated by the U.S. military. Now, it’s classified as a “superfund” site by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency due to the amount of hazardous waste that’s been dumped in it. Eating any fish from there, even swimming in that water, will make you sick.

What makes me most angry about the militarization of our islands is the level of occupation–there’s a monumental amount of land controlled by the military. Much of that area encompasses culturally significant sites.

Soldiers from the U.S. and Mexico in live-fire sniper training at a U.S. military base on the east coast of O’ahu for RIMPAC 2024. Date: July 5, 2024.

On O‘ahu alone, the U.S. military controls about 25 percent of the land. Overall, across the Hawai‘i islands, the military occupies 5.6 percent of the land, according to an analysis of Department of Defence property by Visual Capitalist. That’s the highest proportion of military-controlled land in any U.S. state. There are 11 military bases in Hawai‘i.

Fighting against that presence and control is particularly tough because of the vast resources of the U.S. military and government.

For example, on the west coast of O‘ahu, we’ve managed to stop live-fire training in an area known as Mākua Valley after decades of organizing against it. Locals first came together in 1996 to object to the military exercises. In 2023, following several court cases, the U.S. military finally announced that it had no more plans to conduct any more live-fire training exercises in the area.

Mākua is culturally significant for Kānaka Maoli because it’s where we believe human life was created by Papa (earth mother) and Wākea (sky father). The area was seized during World War Two by the U.S. government, and the families living there were evicted. It was bombed until the early 1990s, creating widespread destruction and harm to the environment and species there. Many of these animals and plants are now endangered as a result.

Notably, the army lease for land at Mākua–a $1 agreement between the state of Hawai‘i and the U.S. Army signed in 1964–is due to expire in 2029. It’s among a suite of lease agreements between the army and state government, which cover about 30,000 acres of land in Hawai‘i. Unsurprisingly, the military is pushing for these leases to be renewed or for new arrangements to be put in place, so it can continue its current operations.

RIMPAC 2022.

On the big island of Hawai‘i, near its center, the U.S. military has created a bombing range in an area we call Pohakuloa. The scale of what happens there is insane.

The Pohakuloa Training Area encompasses about 132,000 acres of land. That’s nearly five times the size of our smallest island, Kaho‘olawe. Like Mākua, Pohakuloa is culturally significant to Kānaka Maoli, particularly because it sits between the peaks of Mauna Kea–where protesters have continually objected to the proposed construction of a 30-meter telescope–Mauna Loa, and Hualālai volcano. In Hawaiian tradition, the peaks of the island’s mountains and volcanoes are sacred.

For the U.S. military, however, Pohakuloa is a giant training ground. Every one of its branches conducts exercises in the area. It’s also used by other countries for bombing practice, for example, during RIMPAC. These bombs and military activities have meant the land can’t be accessed by Hawaiians. Over the years, we’ve seen huge fires and damage to the native flora and fauna. There’s been contamination of the land and waterways by hazardous waste products like uranium, lead, and white phosphorus.

So much of what goes on in these military-occupied areas is about inflicting violence on our land and sacred sites through bullets, bombs, and destruction. I refer to it as bio-colonialism because, at its heart, it’s about wanting to control all forms of life.

Even the military’s own people–servicemen and women and their families–have been left without help when in need.

The Red Hill fuel storage facility in Honolulu is a prime example. During World War Two, the Americans built 20 fuel storage tanks within the mountain of O‘ahu’s largest aquifer. The vertical fuel tanks sat on top of the porous volcanic rock. Critically, 80 percent of the island’s freshwater came from here.

In 2014, and then 2021, there were two massive fuel leaks at the Red Hill facility —27,000 gallons and 21,000 gallons respectively. The first leak didn’t appear to reach the water table. But in 2021, there was contamination of the water supply. The leak primarily affected the water supply which went to areas where navy personnel lived.

In total, it affected 93,000 military personnel and their families. People broke out in skin rashes, became seriously ill, and children developed neurological issues. The fallout from that is ongoing and victims are suing the U.S. government for the harm caused.

That lack of care, decency, and respect is something I’ve been fighting against for a decade.

The entire arrangement, where the U.S. uses Hawai‘i as a strategic war base, is fundamentally violent and harmful. It relies on the perpetual suppression of our rights and potential as Kānaka Maoli.

Joy Enomoto.

We have to see that for what it is. We also need to think long-term about how we’re going to reclaim our own narrative. Because the solutions to the challenges we face, and our prosperity as people, don’t lie with the U.S.. They lie within us and our own vision for the future. For me, that picture is simply incompatible with an occupier that can’t see beyond its own might and colonial mentality.

Joy Lehuanani Enomoto is of Kānaka Maoli, African American, Japanese, Scottish, and Caddo Indian descent. She is a Pacific Islands scholar, community organizer and visual artist. Her work focuses on the demilitarization and de-occupation of Hawai‘i and the Pacific region. Joy was the previous executive director of Hawai‘i Peace and Justice, one of the longest-serving anti-militarization and anti-occupation organizations in Hawai‘i. She lives in Honolulu with her partner.

As told to Teuila Fuatai. Made possible by the Public Interest Journalism Fund.