This article briefly examines the pre-history of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) working definition of antisemitism, and how a combination of domestic and international challenges to Zionism in the late 1960s and early 1970s led to a concerted effort to redefine antisemitism in a way that prioritized the defense of Israel while identifying the political Left as the primary antagonist. It positions the IHRA definition not as a grassroots response to antisemitism, but rather as a coordinated, institutional form of counterinsurgency aimed at snuffing out transnational solidarity with Palestine.

The institutional and legal history of the IHRA definition usually begins in the early 2000s with the so-called “3D test” proposed by Natan Sharansky, then the Minister for Jerusalem and Diaspora Affairs in the Israeli government. Sharansky, a dissident Soviet Jew who emigrated to Israel following his release from prison in 1986 and served in a variety of governmental roles from the 1990s through the early 2000s, came to see non-violent Palestinian solidarity efforts in nearly apocalyptic terms, linking them both to the Nazi genocide and Stalinist “totalitarianism.” In response, Sharansky proposed the so-called “3D test” to distinguish between “legitimate criticism” of Israel and that which fell into the realm of antisemitism. The three “D’s” in question, according to Sharansky, were demonization (“when Israel’s actions are blown out of all sensible proportion”), double standards (“When criticism of Israel is applied selectively; when Israel is singled out. . . for human rights abuses while the behavior of known and major abusers, such as China, Iran, Cuba, and Syria, is ignored”), and delegitimization (“when Israel’s fundamental right to exist is denied”).1 Under this definition, all anti-Zionism was to be understood as a form of antisemitism. Even those who accepted the existence of Israel had to ensure that their criticism stayed within certain bounds and was matched by a proportional critique of other human rights abusers (notably a test not required when other countries are denounced for human rights violations).

In 2005, elements of Sharansky’s “3D test” were enshrined as part of the European Union Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia’s (EUMC) “Working Definition of Anti-Semitism.” Of the 11 examples of antisemitism offered by the drafters, seven involved the state of Israel, including “claiming that the existence of a State of Israel is a racist endeavor.”2 In 2010, the U.S. State Department officially adopted its own definition of antisemitism which was largely identical to that proffered by the EUMC, although it made the “3D test” even more prominent with respect to criticism of Israel.3 Finally, in 2016, the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) adopted a subtly modified version of the EMUC Working Definition which kept intact the 11 examples and their links to the “3D test.”4

Israel and the “New Antisemitism” in the 1970s

While the institutional history of the IHRA is relatively straightforward, if we want to understand both where it came from and what motivated its creation, we have to turn the clock back a number of decades. In that vein, a quote from a book entitled The Real Anti-Semitism in America, written in 1982 by ADL director Nathan Pearlmutter and his wife, Ruth Pearlmutter, is instructive. I’ll warn that the language here is extremely racist, but I’ve included it because it is important to understanding the developments that we are addressing as part of the conference as well as in the larger ongoing struggle to support Palestinian liberation:

Stand with me on the corner of Forty-second Street and First Avenue in New York City in front of the United Nations. Let us watch the diplomats on their way to work. Turbaned men, women in saris, tall Black men and short swarthy men, blond Europeans and yellow Orientals—all well groomed, educated, cosmopolitan. Diplomats. Surely there isn’t one among them who is a Klansman. Surely there isn’t one who would, under night’s cover, furtively sneak onto a Jew’s lawn, daub a swastika on his door. But who threatens Jewish interests more ominously—the diplomats who regularly affirm that Zionism is racism, or the juveniles with paint cans?5

This formulation offered by the Perlmutters is aimed particularly at the United Nations, but it is useful because it so bluntly illustrates a rhetorical and ideological shift that laid the groundwork for the IHRA definition in the 21st century. There are two related elements in this shift. The first is to identify anti-Zionism not only as a form of antisemitism, but also one that is more dangerous than traditional antisemitism which was aimed at Jewish people, either individually or collectively. Second, it identifies this new, redefined antisemitism as emanating from an internationalist Left rather than from the nationalist Right and groups such as the KKK or the American Nazi party. The logic at play here is that the antisemitism of the Right—cross burnings, swastikas, even acts of violence directed at Jewish individuals—might pose a threat to Jews in the United States or Western Europe, but that this threat is dwarfed by the anti-Zionism of the Left, which threatens the entire Israeli settler colonial project. Not only is antisemitism being redefined to include Israel, then, but it is also and quite self-consciously being argued that Left-wing attacks on Zionism are more dangerous than traditional Right-wing antisemitism aimed at Jewish people.

Where, how, and why does this shifting definition of antisemitism originate? While attempts to establish Zionism as a core component of Jewish identity have a long history, it was during the late 1960s and early 1970s that we first see a sustained campaign by Zionist intellectuals and activists to codify this link through an expanded definition of antisemitism focused specifically on Israel and combatting criticism from the Left. In 1969, Austrian intellectual Jean Améry published an essay entitled “Virtuous Antisemitism” in which he argued that “today’s anti-Israelism and anti-Zionism and the antisemitism of yesteryear find themselves in absolute agreement. . . . What certainly is new, however, is that this form of antisemitism, now dressed up as anti-Israelism, is located firmly on the left.”6 By the early 1970s, American Zionist organizations and even elements of the Israeli government had begun to embrace this revised definition. In 1971, David A. Rose, chair of the ADL’s national executive committee, warned that “the anti-Israel hate campaign by these extremists not only poses a serious threat to Israel’s survival, but is, in its broadest sense, anti-Jewish.”7 The following year, at a gathering sponsored by the American Jewish Committee (AJC), Israeli Foreign Minister Abba Eban identified this phenomenon as the “new anti-Semitism” aimed at Israel, one specifically associated with “the rise of the new left.” Staking a claim that would define the shape of Zionist efforts to silence criticism of Israel for the next 50 years, Eban asserted that “the distinction between anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism is not a distinction at all. Anti-Zionism is merely the new anti-Semitism.”8

Two years later, in 1974, ADL director and associate director Benjamin R. Epstein and Arnold Forster published The New Anti-Semitism, which helped to popularize that term as shorthand for an expanded definition of antisemitism that targeted leftist critiques of Israel and Zionism. “In the rhetoric of the black extremist and left revolutionary organizations,” they declared, “‘anti-Zionism’ became a vehicle for anti-Semitism.”9 This quotation from Epstein and Forster not only nicely illustrates the logic of the “new antisemitism” but also hints at the way that Zionist organizations in this period were reacting to larger changes in the domestic political environment in the late 1960s and early 1970s. It’s not a novel insight to say that this period marked a huge institutional transformation among American Jewish organizations, as groups such as the ADL and AJC, which had traditionally been focused on domestic antisemitism, pivoted to place Israel at the center of their agenda, while new groups such as the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC, 1963), Americans for a Safe Israel (AFSI, 1970), and the Committee for Accuracy in Middle East Reporting and Analysis (CAMERA, 1982) were created to explicitly lobby Americans on behalf of Israel. The traditional explanation for this shift has focused on military and diplomatic developments in the SWANA region, including the 1967 and 1973 Arab-Israeli wars and the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon. But while military conflict in the Middle East clearly prompted an evolution in Zionist groups in the U.S. and elsewhere, it doesn’t really explain the push for an expanded and reprioritized definition of antisemitism, a redefinition that focused not on Arab armies or even Palestinian resistance groups such as Fatah or the PFLP but, rather, on what Epstein and Forster dubbed “black extremist and left revolutionary organizations.”

Responding to Grass Roots Movements

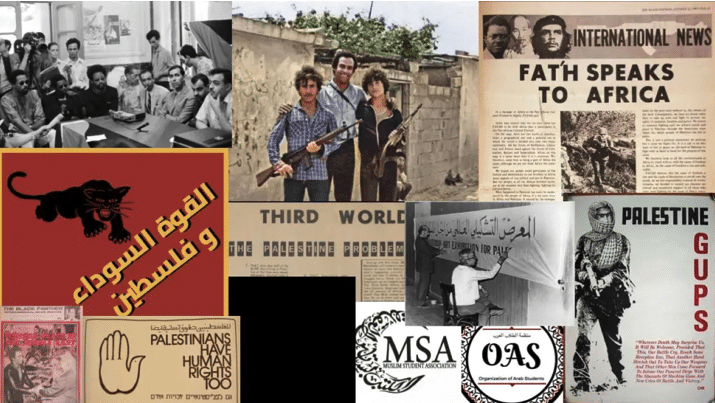

Building on the work of Keith Feldman, Alex Lubin, and others, I would suggest that the primary motivation behind the advent of the “new antisemitism” formulation had little to do with the Arab—Israeli conflict and was instead a response to transnational, grassroots organizing that sought to link anticolonial liberation movements across the globe with activists in the United States and Western Europe. Palestinian solidarity efforts have a long history in the United States, dating back to the 1950s and early 1960s with organizations such as the Organization of Arab Students (OAS, founded 1952), the Muslim Students Association (MSA, 1963), and the Association of Arab-American University Graduates (AAUG, 1967). In the 1970s, several new groups picked up the struggle, including the first U.S.-based chapters of the General Union of Palestine Students (GUPS) as well as the Palestine Human Rights Campaign (PHRC) and the Palestine Solidarity Committee (PSC). Although the tactics and membership of these groups varied, in the aftermath of the 1967 war, many emphasized connections to the revolutionary Third World as well as to domestic groups seeking radical change in the United States. At the same time, during the late 1960s and early 1970s, Black Power activists played a crucial role in bringing Palestinian solidarity efforts from a relatively fringe position to one that, at the very least, demanded public attention. Drawing from figures ranging from Malcolm X and cultural critic Harold Cruse to Che Guevara and Frantz Fanon, organizations such as the Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM) and the Black Panther Party (BPP) and elements within the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) all embraced an analysis in which Black Americans were not citizens unjustly denied their rights, but rather the victims of internal colonialism that must be overthrown by any means necessary. This analysis, which was heavily influenced by the Algerian and Cuban revolutions as well as the resistance of the Vietnamese against French and American imperialism, predated the 1967 war in the Middle East. But the post-1967 Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza, combined with U.S. collaboration in the Israeli war effort at the height of the Vietnam War, led many in the Black Power movement to explicitly link the two nations as inherently violent, imperial projects that needed to be forcibly confronted by any means necessary.

In part as a result of the example set by the Black Power movement, elements within the predominantly white American New Left also became critical of the Zionist project in the aftermath of the 1967 war.10 Anticipating later activist efforts in the 21st century, students in the late 1960s organized “Palestine weeks” on their campuses, distributed anti-Zionist literature linking Israel to apartheid, and organized clubs and groups centered around Palestinian solidarity.11 As with Black Power activists, the New Left critique of Israel was linked to a larger global analysis in which both Israel and the United States were implicated in colonialism and imperialism.

This is obviously a very truncated and incomplete history of Palestinian organizing and solidarity efforts in the 1960s and 1970s, but it is against this backdrop of grassroots, multi-racial, multi-ethnic, transnational anticolonial organizing that we need to understand the creation of the “new antisemitism” with its emphasis on defending Israel against what would later come to be called delegitimization efforts from this grassroots coalition.

Conclusion and Significance

In closing, I want to briefly address why this brief pre-history of the IHRA matters to the larger issues of theory and activism that animate this conference. It’s an easy historian’s trick to point to any particular issue and say “ah ha! This happened earlier than you think it did!” While that may often be true, I’m also sympathetic with those who ask why we should care. In light of the genocide and ongoing Nakba in Palestine, what difference does it make if the roots of the IHRA definition are in the late 1960s or in the early 2000s? To that end, I want to offer three observations.

First, this history makes clear that this revised definition of antisemitism focused on Israel and Zionism did not arise organically from Jewish communities in the United States or elsewhere. Rather, both the IHRA definition and its precursor in the form of the “new antisemitism” were the results of a coordinated campaign by Zionist groups and the Israeli government to stamp out attacks on Israel from the Left as well as to discredit efforts to link global anticolonial movements across borders. We need to forthrightly address this for what it was and what it is: a form of counterinsurgency aimed at shoring up Zionism and defeating not only resistance in Palestine, but also any form of coordinated Palestinian solidarity across national, racial, and ethnic borders. This counterinsurgency began with epistemic efforts to redefine antisemitism in the 1960s and 1970s and escalated, in the 21st century, into a campaign to make that revised definition binding in a way that can be enforced by institutions ranging from universities and police forces to cities, states, and national governments.

Second, and relatedly, we need to understand both the “new antisemitism” and the IHRA definition as a testament to the success of grassroots activism around Palestine and the threat that it poses not just to Israel, but also to Zionism as an ideology as well as to settler colonialism and apartheid more broadly, including struggles in North America against police violence and indigenous dispossession. I do not want to overplay the role of solidarity networks in the West and elsewhere; this struggle began in Palestine and it will end with a Palestine that is free from the river to the sea. And while activists and academics have paid, and continued to pay, real costs for Palestinian solidarity, it is those on the ground in Palestine who suffer under not only Israeli bombs and guns but also the grinding slow death of Israeli necropolitics. That said, I think it is telling that even in the late 1960s and early 1970s, at a time when most of the world was focused on the very active Arab-Israeli military conflict, Zionist organizations and elements of the Israeli government had already singled out transnational grassroots solidarity efforts as enough of a threat to warrant a fundamental redefinition of antisemitism. It is not a coincidence that those efforts were revived and redoubled in the early 2000s in response to a new wave of transnational organizing around BDS and Palestinian solidarity.

Third and finally, I think this history reminds us of the importance of critical Zionism studies and critical ethnic studies as tools for both knowledge production and activism. Failure to critically examine the history, theory, and practice of Zionism leaves Zionists to define the terrain of debate. Critical ethnic studies at its best offers an intellectual and institutional space that channels the kind of transnational, multi-racial, multi-ethnic organizing and activism that marked both its birth as a discipline and the larger anticolonial struggles of the 1960s and 1970s. We could have a whole conference on the perils of ethnic studies as an institutionalized formation within the Western academy, but when I look at this room today, I see lots of people who have leveraged the institutional and intellectual power of critical ethnic studies to continue and expand the struggles that gave birth to this discipline, while linking those struggles to the cause of Palestine and other colonized peoples. I also do not think it is a coincidence that here in California and elsewhere, Zionist organizations have made targeting, censoring, and suppressing critical ethnic studies a crucial part of their contemporary agenda.

This article first appeared in Volume 1, Issue 1 (Fall 2024) of the Journal for the Critical Study of Zionism (JCSZ) under the title “From the “New Antisemitism” to the IHRA Definition.”

Sean L. Malloy is a Professor of History and Critical Race and Ethnic Studies (CRES) at the University of California, Merced. He received his Ph.D. and MA in History from Stanford University and a BA in History from the University of California, Berkeley. He is the author of Atomic Tragedy: Henry L. Stimson and the Decision to Use the Bomb Against Japan (Cornell University Press, 2008) as well as articles dealing with nuclear targeting in World War II and the radiation effects of the atomic bomb. His most recent book, Out of Oakland: Black Panther Party Internationalism During the Cold War, was published by Cornell University Press in 2017. His current research project examines the countermobilization against Palestinian solidarity efforts at U.S. universities.

Notes:

- 1. Natan Sharansky, “3D Test of Anti-Semitism: Demonization, Double Standards, Delegitimization,” Jewish Political Studies Review, 16: 3-4 (Fall 2004).

- 2. Michael Whine, “Progress in the Struggle Against Anti-Semitism in Europe: The Berlin Declaration and the European Union Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia’s Working Definition of Anti-Semitism,” Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, February 1, 2006: https://www.jcpa.org/phas/phas-041-whine.htm.

- 3. Kenneth Marcus, The Definition of Anti-Semitism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), pp. 166-169; U.S. State Department, Special Envoy to Monitor and Combat Anti-Semitism, “Defining Anti-Semitism,” June 8, 2010: https://2009-2017.state.gov/j/drl/rls/fs/2010/122352.htm.

- 4. International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, “About the IHRA non-legally binding working definition of antisemitism,” https://www.holocaustremembrance.com/resources/working-definitions-charters/working-definition-antisemitism.

- 5. Nathan Perlmutter and Ruth Perlmutter, The Real Anti-Semitism in America (New York: Arbor House, 1982), p. 106.

- 6. Jean Améry, “Virtuous Antisemitism,” Essays on Antisemitism, Anti-Zionism, and the Left, ed. Marlene Gallner (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2021), p. 34.

- 7.“ADL Warns Opposition to Israel and U.S. Support for State May Replace Vietnam as Issue for Left, Right,” JTA Daily News Bulletin, November 23, 1971, p. 4.

- 8. Abba Eban, “Our Place in the Human Scheme,” Congress Bi-Weekly: A Journal of Opinion and Jewish Affairs, Vol. 40, No. 6 (March 30, 1973), p. 7.

- 9. Forester and Epstein, The New Antisemitism,189.

- 10. Fishbach, The Movement and the Middle East, 25.

- 11. Ibid., 26-28.