Donald Trump has repeated in recent days, often in capital letters on his Truth Social account, that Iran cannot be allowed to obtain a nuclear weapon.

His view is shared by Benjamin Netanyahu, Israel’s prime minister, who has said that Israel’s surprise attack on Iran, which has killed hundreds since 13 June, is a pre-emptive measure to stop Iran from creating a nuclear weapon.

Iran denies it is trying to produce nuclear arms, and that its nuclear programme is for civilian purposes.

It is a signatory to the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), which says that states that do not already have nuclear weapons cannot obtain them.

The NPT gives the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) the power to monitor and verify that non-nuclear states are complying.

Last week, the watchdog said that Iran had breached its obligations—an action Tehran strongly condemned, and claimed provided a pretext for Israel’s surprise assault.

But unlike Iran, Israel has not signed the NPT, and is one of only five countries not to be party to the 1968 treaty. This means that the IAEA has no way to monitor or verify Israel’s nuclear arsenal.

Little is known about Israel’s nuclear programme, which it has a policy of neither confirming nor denying.

However, declassified documents, investigative research and whistleblower revelations from the 1980s have pointed to what it has.

What nuclear weapons does Israel possess?

Israel is one of nine countries that are known to have nuclear weapons, along with the US, Russia, the UK, France, China, India, Pakistan and North Korea.

It is believed to possess around 90 nuclear warheads and enough plutonium to produce around 200 more nuclear weapons, according to the Nuclear Threat Initiative.

Israel has between 750 and 1,110kg of plutonium, which would be enough to build 187 to 277 nuclear weapons.

An Israeli Air Force F-35 Lightning II fighter jet performs during a graduation ceremony of Israeli Air Force pilots on 28 December 2022 (AFP/Jack Guez)

These presumed weapons can be fired from the air, sea and land.

Israel owns U.S.-produced F-15, F-16 and F-35 aircraft, all of which can be modified to hold nuclear bombs. It is also believed to have six Dolphin-class submarines, produced by a German company, which may be capable of launching nuclear cruise missiles.

The land-based Jericho family of ballistic missiles has a range of up to 4,000km. Researchers estimate that around 24 of these can carry nuclear warheads, although the exact number is unclear.

How did Israel’s nuclear programme begin?

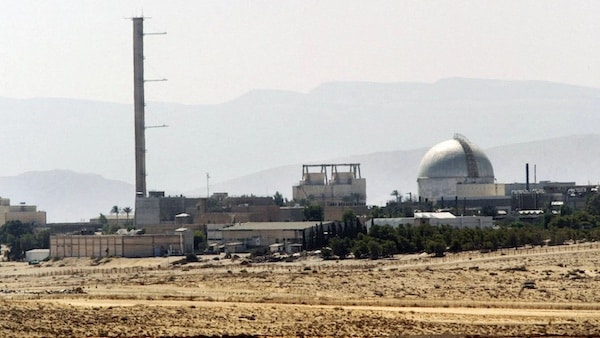

David Ben Gurion, Israel’s first prime minister, launched the nuclear project during the mid to late 1950s. A large complex was built at Dimona, a city in the Negev desert (the site is referred to simply as “Dimona”).

It was there that the first batch of plutonium was produced, with help from the French government.

“Most credible accounts point to France’s role in the late 1950s,” Shawn Rostker, a research analyst at the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation, told Middle East Eye.

It helped build the Dimona reactor, supplied key reactor technology, and backed plutonium reprocessing capabilities, laying the groundwork for Israel’s nuclear progress.

The coordination between Paris and Israel was born out of a shared hostility towards Gamal Abdel Nasser, Egypt’s then-president, according to French historians.

French-Israeli cooperation was kept secret: even the U.S., Israel’s closest ally, was initially unaware.

Avner Cohen, an Israeli-American historian and professor, is one of the most prominent researchers on Israel’s nuclear history and has written several books on the subject, including Israel and the Bomb.

“About half a century ago Israel acquired nuclear weapons capability, but it has done so in a manner unlike any other nuclear weapons state did, prior or after,” he told Middle East Eye.

His research, which includes analysis of recently declassified U.S. documents, found that Washington during the late 1950s and early 1960s repeatedly questioned Israel about what it was doing at Dimona.

Eventually, under U.S. pressure, Ben Gurion told the Knesset in December 1960 that the Dimona reactor was “a research reactor” which would serve “industry, agriculture, health and science”.

Thus began an elaborate and long-running deception, as U.S. officials inspected the site on eight occasions between 1961 and 1969.

During these visits, an underground separation plant, essential for the production of weapons-grade plutonium, was concealed. Other parts of the site were camouflaged to disguise the purpose of the complex.

Israel was making significant progress between the visits.

It is believed to have completed its secret underground separation plant by 1965; to have begun producing weapons-grade plutonium by 1966; and to have assembled a nuclear weapon before June 1967 and the start of the Middle East war.

What was the 1969 Nixon-Meir deal?

By the end of the 1960s, the U.S. had finally learnt the true purpose of Dimona. According to Cohen, a secret deal was struck, still in place, that Washington would not ask questions if Israel kept quiet.

“In 1969, the U.S. accepted the Israeli exceptionalist nuclear status, as long as Israel was committed to keeping its presence invisible and opaque. This is known as the 1969 Nixon-Meir nuclear deal,” Cohen told MEE, referring to then-leaders Richard Nixon and Golda Meir.

Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir listens to American President Richard Nixon at the White House in Washington on 1 March 1973 (AFP)

Since then, Israel has kept to its side and operated a policy of deliberate obscurity, with officials neither acknowledging nor denying the existence of a nuclear arsenal.

The U.S. has gone along with it, even reportedly issuing t hreats of disciplinary action against any U.S. official who publicly acknowledges the programme.

In 2009, U.S. President Barack Obama was asked whether any countries in the Middle East had nuclear weapons. He replied that he would not speculate.

Has Israel tested nuclear weapons?

Of the nine nuclear powers, Israel is the only one not to have openly conducted a nuclear test.

The closest evidence has been what is known as the “Vela incident” in September 1979, when Israel and apartheid era-South Africa may have conducted a joint nuclear test on an island where the South Atlantic meets the Indian Ocean.

U.S. satellites at the time detected an unexplained double flash of light, usually a tell-tale sign of a nuclear blast.

South Africa’s apartheid government developed weapons of mass destruction for five decades, but ended its nuclear programme in 1989. It is the only country to have achieved nuclear weapon capability but relinquished it voluntarily.

Jimmy Carter, who was U.S. president at the time of the incident, said he believed the Vela incident to have been an Israeli nuclear test.

“We have a growing belief among our scientists that the Israelis did indeed conduct a nuclear test explosion in the ocean near the southern end of South Africa,” he wrote in White House Diary, an annotated version of a journal kept during his presidency published in 2010.

When did Israel’s nuclear weapons become widely known?

Israel’s nuclear programme hit the headlines in October 1986, when former nuclear technician Mordechai Vanunu revealed details about Dimona to the Sunday Times.

Vanunu, who had worked at the site for nine years, said it was capable of producing 1.2kg of plutonium a week, which would be enough for around 12 nuclear warheads a year.

He said that during the U.S. visits in the 1960s, American officials had been tricked by false walls and concealed elevators, and that they were unaware that there were a further six floors hidden underground.

Former Israeli nuclear technician Mordechai Vanunu walks free out of the high security prison of Shikma in Askelon, southern Israel, on 21 April 2004 (AFP/Menahem Kahana)

Vanunu took 60 pictures of Dimona, several of which were published by the British newspaper.

In the years running up to leaking the information, Vanunu had become disillusioned with Israel’s actions, opposing its invasion of Lebanon in 1982 and calling for equal rights for Palestinians.

But before his story was even published, Vanunu was abducted by Israeli agents. Staying in London at the expense of The Sunday Times, he was persuaded by a female Mossad agent to go to Rome. There he was, drugged, taken to Israel, found guilty of espionage and served 18 years in prison—more than half in solitary confinement.

Upon his release in 2004, he was banned from travelling or speaking to foreign journalists. Those restrictions remain in place.

What is Israel’s strategy for using nuclear weapons?

In 2011, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was asked by Piers Morgan to confirm that Israel doesn’t have nuclear weapons. He replied: “That’s our policy. Not to be the first to introduce nuclear weapons into the Middle East.” It’s a line that is often repeated by Israeli officials when pressed on the issue.

“Israel never clarified publicly what ‘introduction’ means,” said Cohen, adding that Israel treated nuclear activities as classified and outside of its defence and foreign policies.

Hence, Israel has no public strategy involving nuclear use. It is understood that Israel sees no use of nuclear weapons except in the most extreme scenarios of ‘last resort’.

It is also widely understood that as long as Israel maintains its regional benign monopoly, it does not view its capability as weapons.

The “scenario of last resort” is sometimes referred to as “the Samson Option”, a phrase believed to have been coined by Israeli leaders during the mid-1960s. The principle is that Israel would use nuclear retaliation if it faced an existential threat.

Samson was a biblical Jewish figure who, chained by his enemies, the Philistines, in a temple, used his God-given strength to collapse a pillar, killing himself and his captors.

It is in stark contrast, say analysts, to the doctrine of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD), where if one nuclear power pre-emptively attacked another, then the targeted nation would still have time to retaliate, ensuring neither would survive.

But in theory, the Samson Option could apply if Israel faces a military defeat that it considers existential, even from a non-nuclear power.

Cohen and several other researchers have said that during the Middle East war of 1973, when Egypt and Syria mounted a surprise attack, Israel considered the option.

But while they have never admitted the existence of nuclear weapons, Israeli leaders have implied that they can be used if necessary.

“Our submarine fleet acts as a deterrent to our enemies,” Netanyahu said in a 2016 speech.

They need to know that Israel can attack, with great might, anyone who tries to harm it.

More recently, in November 2023, a government minister publicly suggested that Israel dropping a nuclear bomb on the Gaza Strip was “an option”.

Amichai Eliyahu, Israel’s heritage minister, was briefly suspended from government meetings for the comments, and later took to social media to state that it was meant to be “metaphorical”.

What’s the world said about Israel’s nuclear weapons?

Israel is one of only five states that are not party to the NPT, the 1968 treaty which sought to bring nuclear weapons use under international control.

India and Pakistan have never signed the treaty. North Korea signed it but withdrew in 2003. South Sudan is the only non-signatory which does not have nuclear weapons.

In December 2014, the UN General Assembly overwhelmingly voted (by 161 votes to five) to approve a resolution urging Israel to renounce the possession of nuclear weapons, accede to the NPT “without further delay” and place all of its nuclear facilities under the safeguards of the IAEA. The resolution was non-binding. Israel has not complied.

“Israel is a sovereign country and will make decisions based on its own security and interests,” said Rostker.

That said, a more open approach could help build confidence and reduce nuclear tensions without compromising deterrence.