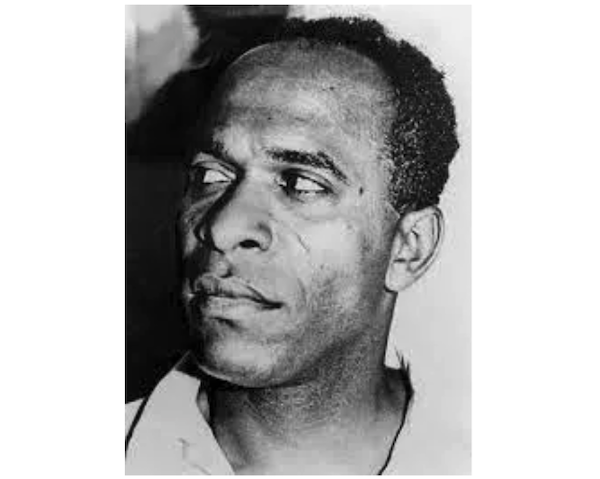

Frantz Fanon is widely known for his uncompromising insistence that colonialism can only be overthrown through violence. For Fanon, violence is not simply a tactic; it is the very essence of the colonial relation. Colonialism enforces its will through systemic, racialised violence, and it is only through a corresponding force, armed struggle, that the colonised can hope to break the chains of domination. Much has been made of Fanon’s reflections on the psychological effects of violence, especially its cathartic potential. The act of resistance, he argued, enables the colonised to reclaim a sense of agency and dignity long denied them. Yet to reduce Fanon’s intervention to a theory of revolutionary therapy would be to miss the core of his political project.

The central concern of The Wretched of the Earth is not merely how colonialism is to be overthrown, but what kind of society should emerge in its aftermath. For Fanon, the form that the anti-colonial struggle takes—and, crucially, who participates in and leads it—is decisive in shaping the post-colonial future. His project, then, is a class analysis of the colonised world, an attempt to map the contradictory and uneven terrain of colonial societies in order to understand both the possibilities and the limitations of revolutionary transformation.

Fanon’s principal distinction is between the rural masses and the urban classes within the colonial social formation. In the cities, he focuses first on the so-called “national bourgeoisie,” that is, indigenous elites composed of professionals, merchants, and intermediaries: “doctors, lawyers, tradesmen, agents, dealers, and shipping agents,” as he puts it (Fanon [1961] 2004, 100). This class had long been viewed by some on the Left as potentially progressive, especially when contrasted with the ‘comprador bourgeoisie’ tied directly to foreign capital. In this view, the national bourgeoisie could serve as a junior partner in the revolutionary project, helping to build a post-colonial order through class compromise.

Fanon, however, turns this thesis on its head. He does not deny that there is a convergence of interests between the national bourgeoisie and certain segments of the urban working class, but he insists that this convergence operates against the popular classes. It serves the reproduction of elite power, not its abolition. The national bourgeoisie, far from being a transformative force, seeks not to dismantle the colonial social order but to inherit it—to replace the white administrator with the black one while leaving the underlying class structure intact.

In this context, Fanon is especially critical of the urban proletariat. In the Algerian case, this class is both small and disproportionately privileged, forming what he calls a “pampered” stratum, a kind of labour aristocracy in a sea of rural poverty (Fanon [1961] 2004, 75). Unlike orthodox Marxist accounts that place revolutionary hopes in the industrial working class, Fanon sees the urban proletariat as being largely invested in the continuation of existing hierarchies. Its horizon is not liberation, but assimilation into the colonial system’s material rewards.

Thus, Fanon rejects the idea that the national bourgeoisie and the urban working class constitute a reliable revolutionary bloc. Their interests, shaped by proximity to colonial structures and benefits, tend toward accommodation rather than rupture. Their project is not social transformation but succession, trading one ruling elite for another, without altering the foundations of exploitation.

If Fanon offers a withering critique of the urban classes under colonial rule, it is in the peasant masses that he locates the most potent revolutionary potential. The colonised peasantry, largely dispossessed of land and alienated from the means of subsistence and identity, becomes, in Fanon’s eyes, the only truly revolutionary class within the colonial order. In a pointed echo of Marx and Engels’ famous injunction in The Communist Manifesto, Fanon writes:

It is clear that in the colonial countries the peasants alone are revolutionary, for they have nothing to lose and everything to gain (Fanon [1961] 2004, p. 23).

This is not to romanticise the peasantry. Fanon is clear-eyed about the limitations of this class as well. The peasant masses are capable of extraordinary acts of revolt and resistance, but they lack a coherent political vision. Their uprisings are spontaneous and insurgent, not strategic or programmatic. What they require is a unifying project, an organised, long-term vision of transformation.

This is where Fanon introduces the figure of the radical intellectual. Often cast out from the cities by the national bourgeoisie, these intellectuals find themselves in the rural hinterlands. It is there, in exile, that they undergo a kind of political reconstitution. Living among the peasantry, they cease to be mere transmitters of elite ideology and begin to operate, in Gramscian terms, as organic intellectuals (Fanon [1961] 2004, 78-79). Though Fanon had likely never read Gramsci, his formulation resonates with Gramsci’s notion of intellectuals who emerge from and remain rooted in the struggles of subaltern classes.

In this symbiotic relationship between radical intellectuals and the peasantry, a new revolutionary subjectivity is forged. There is mutual education: the intellectuals learn the material and cultural logic of rural life, while the peasants acquire the tools of political consciousness and strategic vision. It is this alliance, not the national bourgeoisie and its urban allies, that Fanon sees as the potential basis for a genuinely emancipatory transformation of the post-colonial order.

Alongside these groups stands another, often misunderstood class: the lumpenproletariat. These are primarily landless rural migrants, expelled from traditional village life and now clustered in the peripheries of colonial cities (Fanon [1961] 2004, 66). Fanon regards them as politically ambivalent, capable of being mobilised in either direction. Rootless, they may become reactionary instruments in the hands of colonial or nationalist elites—or, under the right leadership, a volatile force for radical change (Fanon [1961] 2004, 69, 81). The critical question, then, is which alliance will prove dominant: the one between the national bourgeoisie and the labour aristocracy, or the one uniting the peasantry with radical intellectuals?

For Fanon, the answer carries far more than theoretical significance. The class alliance that leads the struggle determines the character of the post-colonial state. And Fanon is adamant that the path followed by the bourgeois revolutions of the West, however limited or compromised, is not available in the colonial world. Over and over in The Wretched of the Earth, Fanon contrasts the historical development of Western capitalism with that of the colonial periphery. In the metropole, the bourgeoisie was able to establish hegemony, build a civil society, and make strategic concessions. There, liberal democracy, however distorted, became the form through which bourgeois rule was legitimated and sustained.

In the colonies, this route is blocked. The national bourgeoisie, unlike its Western counterpart, lacks an independent economic base. It does not accumulate capital in any meaningful sense, nor does it invest productively. Bereft of material resources, ideological coherence, and popular legitimacy, it is incapable of organising hegemony. As a result, it remains tethered to narrow self-interest, unable to articulate a national-popular project.

The result is a steady degeneration. What begins as an attempt to construct hegemony, a multi-party democracy, quickly slides into a one-party state and, from there, into open dictatorship (Fanon [1961] 2004, p. 111). Without an economic base, the post-colonial ruling class can rule only through coercion, not consent (Fanon [1961] 2004, p. 116). This breakdown gives rise to xenophobia and renewed racism, now turned inward. Where the Western bourgeoisie projected its internal contradictions outward, through empire, the post-colonial bourgeoisie turns on its own people, unable to satisfy the expectations it helped to raise (Fanon [1961] 2004, 108-110).

At the heart of this failure is the structural position of the national bourgeoisie. It is not an autonomous class but an appendage of international capital. Fanon offers a devastating summation: “The national bourgeoisie, with no misgivings and with great pride, revels in the role of agent in its dealings with the Western bourgeoisie” (Fanon [1961] 2004, 101). It is a comprador class in nationalist dress, reproducing the very dependencies it claims to have overthrown.

But there is a second road, what Fanon calls the liberation struggle. If the national bourgeois road leads to degeneration and authoritarianism, the socialist road offers a transformative alternative. In The Wretched of the Earth, Fanon articulates a vision in which the alliance between the peasantry and radical intellectuals becomes the vanguard of this alternative path. He writes lyrically about how this process unfolds through the formation of a political party genuinely accountable to its members. Fanon is almost utopian in his enthusiasm for the participatory nature of this new political formation, envisioning mutual engagement between the party and the people (Fanon [1961] 2004, 127-128). He imagines a form of grassroots democracy where, for instance, building a bridge collectively becomes a moment of political identification, a way for people to recognise themselves as agents within a national project.

Crucially, Fanon emphasises the importance of education, not merely for the masses, but also for leaders. He insists that political leadership must be educable, and that educators themselves must be open to being transformed in the process (Fanon [1961] 2004, 138). These passages offer a compelling, poetic glimpse into the emancipatory possibilities of a socialist future grounded in collective labour, accountability, and mutual education.

Yet Fanon is not naive. He recognises the structural constraints facing the national liberation project. Is this alternative feasible? What are its limits? Here, Fanon introduces the notion of reparations. Given the centuries of plunder and exploitation, he argues, the West owes reparations to the formerly colonised world (Fanon [1961] 2004, 58-59). But why would the West comply? Fanon’s answer is that the Third World holds a form of leverage: its markets. If the newly liberated nations sever themselves from the circuits of Western capital, they may help precipitate a crisis at the heart of the global system.

Ultimately, however, the success of this socialist road hinges on international solidarity, specifically, the awakening of the Western working class. In a powerful metaphor, Fanon likens them to a “Sleeping Beauty,” slumbering while the structures of imperialism and capital grind on (Fanon [1961] 2004, p. 62). The socialist project in the periphery, in other words, is not self-contained; its future is entangled with the fate of class struggle at the global level.

Sam Chian teaches economics and social studies at an upper secondary school in Oslo, Norway. He holds a Master’s degree in sociology from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU). He has published a research article for the Review of African Political Economy that examines Immanuel Wallerstein’s career as an Africanist.