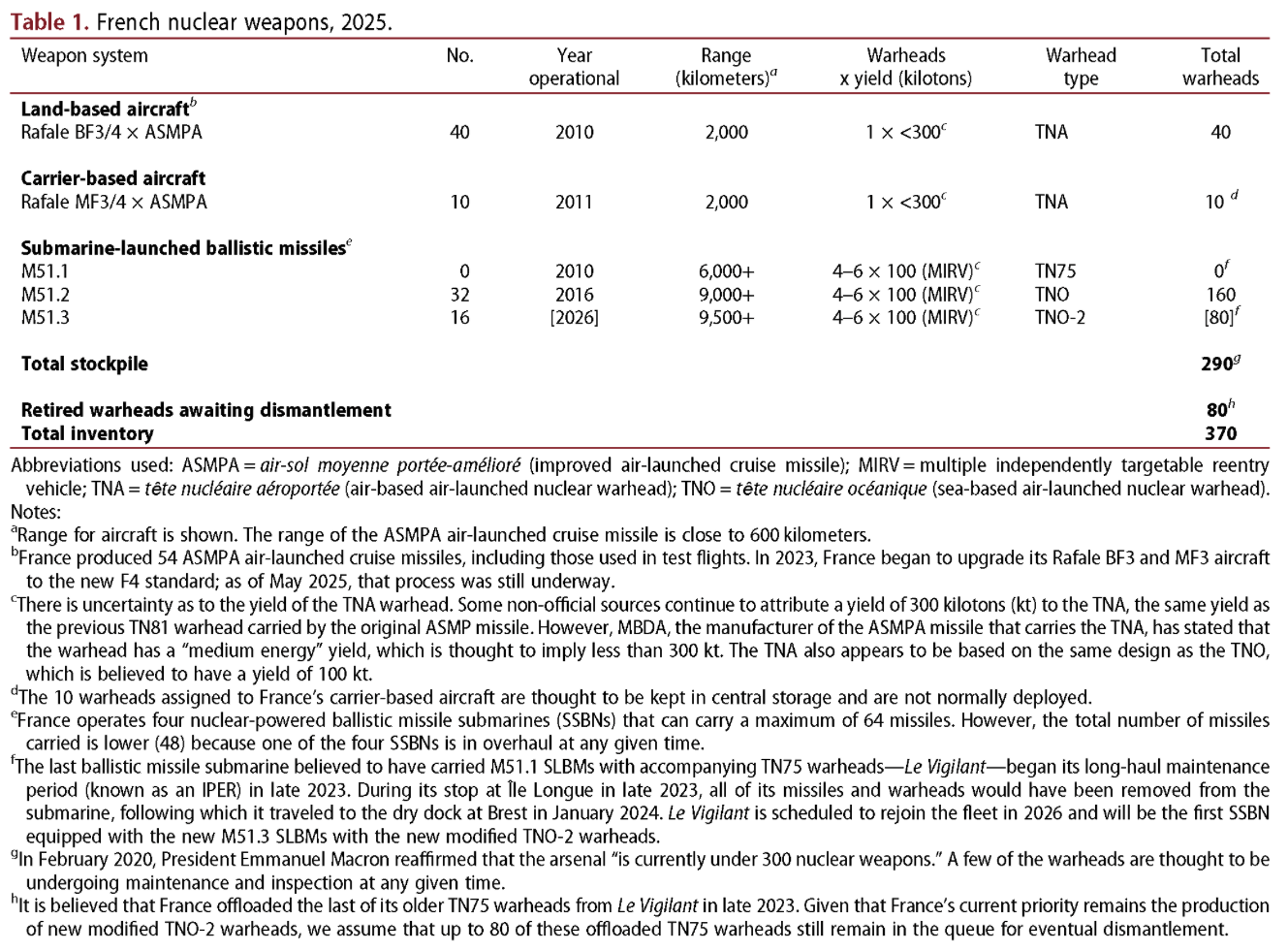

France’s nuclear weapons arsenal has remained stable in recent years, but significant modernizations are underway of the country’s ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, submarines, aircraft, and nuclear industrial complex. We estimate that France currently has a nuclear weapons stockpile of approximately 290 warheads. In addition, approximately 80 retired warheads are awaiting dismantlement, giving a total inventory of approximately 370 nuclear warheads. The Nuclear Notebook is researched and written by the staff of the Federation of American Scientists’ Nuclear Information Project: director Hans M. Kristensen, associate director Matt Korda, and senior research associates Eliana Johns and Mackenzie Knight-Boyle.

This article is freely available in PDF format in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists’ digital magazine (published by Taylor & Francis) at this link. To cite this article, please use the following citation, adapted to the appropriate citation style: Hans M. Kristensen, Matt Korda, Eliana Johns, and Mackenzie Knight-Boyle, 2025. French nuclear weapons, 2025. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 81(4), 313—326. https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2025.2524251

To see all previous Nuclear Notebook columns, go to thebulletin.org

France’s nuclear weapons stockpile has remained stable over the past decade and contains approximately 290 warheads for delivery by ballistic missile submarines and aircraft. Nearly all of France’s stockpiled warheads are deployed or operationally available for deployment on short notice. In addition, up to 80 warheads—the older TN75 warheads assumed to have been recently removed from the Le Vigilant submarine—are believed to be in the dismantlement queue and are likely no longer considered part of France’s stockpile.

The current force level is the result of adjustments made to France’s nuclear posture following former President Nicolas Sarkozy’s announcement on March 21, 2008, that the arsenal would be reduced to fewer than 300 warheads (Sarkozy 2008). As Sarkozy said in 2008, the 300-warhead stockpile is “half the maximum number of warheads [France] had during the Cold War” (Sarkozy 2008). By our estimate, the French warhead inventory peaked in 1991-1992 at around 540 warheads, and the size of today’s stockpile is about the same as it was in 1984, although the composition is significantly different.

President Emmanuel Macron reaffirmed the Sarkozy formulation of “under 300 nuclear weapons” in a speech on February 7, 2020 (Élysée 2020) (see Table 1). Under President Macron, France has engaged in a long-term modernization and strengthening of its nuclear forces, which have included significant budget increases to the deterrent force in recent years (Assemblée Nationale 2024). It is possible but unclear if the decision to add another nuclear air base will increase the stockpile.

Research methodology and confidence

The analyses and estimates made in this Nuclear Notebook are derived from a combination of open sources: (1) state-originating data (e.g. government statements, declassified documents, budgetary information, and military operations and exercises); (2) non-state-originating data (e.g. media reports, think tank analyses, and industry publications); and (3) commercial satellite imagery. Because each of these sources provides different and limited information that is subject to varying degrees of uncertainty, we crosscheck each data point by using multiple sources and supplementing them with private conversations with officials whenever possible.

As a democracy with an active civil society and media landscape, it is possible to obtain relatively higher-quality information about France’s nuclear arsenal compared to many other nuclear-armed countries. France is one of only two countries (the other being the United States) that have publicly disclosed the size of their nuclear stockpile. French policy and military officials also offer regular statements on France’s nuclear doctrine and associated modernization programs.

Despite these positive steps, some challenges persist in obtaining reliable information about France’s nuclear arsenal. France’s freedom of information laws are more restrictive than in the United States and United Kingdom, and since 2008, a law initially designed to limit proliferation of French nuclear information has in practice been implemented on such a broad scale that it has restricted the ability of researchers and journalists to effectively analyze and disseminate data about discrete elements of France’s nuclear stockpile (Cooper 2022; Légifrance 2008). As a result, it is highly challenging to verify information presented by official sources, particularly as such statements rarely contain technical details.

In addition, no other country produces public intelligence assessments or statements about France’s nuclear arsenal, unlike how the United States does with China or Russia. While such statements can be institutionally biased and often reflect a mind-set of worst-case thinking, they still constitute valuable data points to cross with other sources.

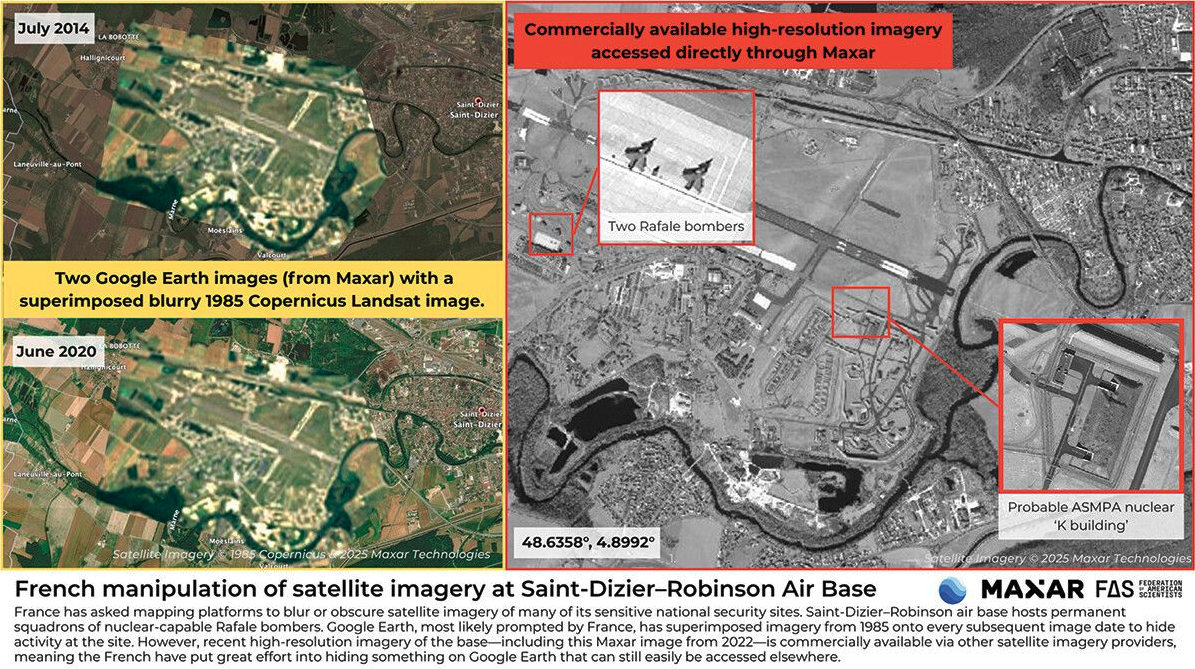

Where gaps in reliable or official data exist, commercial satellite imagery is an important resource for analyzing France’s nuclear forces. Satellite imagery makes it possible to identify air, missile, and navy bases, as well as industrial production facilities. However, over the past decade, France has taken steps to ensure that its most sensitive sites be blurred on public mapping platforms. This censorship appears to have spiked following a helicopter prison jailbreak in 2018, after which France’s Justice Minister asked Google to blur imagery of all of its prisons, remarking that “I think that it’s not normal for secure establishments like prisons to be found on the internet” (Deleaz and Hue 2018; our translation). Although this is in fact very normal practice in almost all other countries, Google appears to have complied: satellite imagery of all French nuclear-related sites, including historical imagery, is now blurred on Google Earth. For example, the nuclear air base at Saint Dizier-Robinson is hidden behind an old low-resolution image from 2014 (see Figure 1).

It is not difficult for imagery analysts to find ways of getting around these censorship practices, as these requests only apply to companies that are either subject to French law or are amenable to French governmental requests for commercial reasons. Given the proliferation of publicly available satellite imagery, it is therefore still possible to acquire high-resolution imagery of all facilities in France. But on Google Earth, France is more sanitized than any other nuclear-armed state.

Considering all these factors, we maintain a higher degree of confidence in our analysis of France’s nuclear arsenal than in that of some other nuclear-armed countries where official and unofficial information is even more scarce (China, Pakistan, India, Israel, and North Korea). However, for certain elements of France’s nuclear deterrent—including command, control, and communications, or the performance of certain weapon systems—information is much scarcer than in other countries like the United States or the United Kingdom.

The role of French nuclear weapons

Successive heads of state, including Presidents Sarkozy, Hollande, and now Macron, have periodically described the role of French nuclear weapons. The Defense Ministry’s 2017 Defense and National Security Strategic Review reiterated that the nuclear doctrine is “strictly defensive,” and that using nuclear weapons “would only be conceivable in extreme circumstances of legitimate self-defense,” involving France’s vital interests. What exactly these “vital interests” are, however, remains unclear. During and after the Cold War, French leaders considered France’s “vital interests” to extend beyond its national boundaries; this discourse has been revived in earnest with the presidency of Emmanuel Macron. In February 2020, President Emmanuel Macron announced that France’s “vital interests now have a European dimension,” and sought to engage the European Union on the “role played by France’s nuclear deterrence in [its] collective security” (Élysée 2020).

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the heightened possibility of nuclear use in Europe, this discourse came under greater scrutiny and analysis. In October 2022, Macron clarified that France’s vital interests “would not be at stake if there was a nuclear ballistic attack in Ukraine or in the region,” apparently attempting to avoid being seen as expanding French nuclear doctrine (France TV 2022). Explicitly ruling out a nuclear role in case of Russian nuclear escalation in Ukraine appeared to contradict France’s statement at the August 2022 Review Conference for the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, which explained that “for deterrence to work, the circumstances under which nuclear weapons would [or would not] be used are not, and should not be, precisely defined, so as not to enable a potential aggressor to calculate the risk inherent in a potential attack” (2020 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons 2022).

The discussion around the role of France’s deterrent in Europe has intensified after the election of Donald Trump as U.S. President, and even more so given the Trump administration’s open disdain for the United States’ European allies, overtures toward Russia, and threats to stop supporting Ukraine. While the broad contours of France’s nuclear posture will likely remain largely unchanged for the near future, how it is communicated and demonstrated appear to be evolving (Maitre 2025).

In addition to statements about France’s vital interests in Europe, Macron announced in March 2025 the addition of a nuclear air base at Luxeuil in eastern France, which will become the first base to house France’s new hypersonic nuclear cruise missile by 2035 (Élysée 2025). And when French jets (including Rafale jets from the nuclear base at Saint Dizier) deployed to northern Sweden in April 2025, France’s ambassador to Sweden explicitly stated: “As President Macron has said, it is of course the case that our French vital interests also include the interests of our allies. In that perspective, the nuclear umbrella also applies to our allies and of course Sweden is among them” (Granlund 2025).

There’s no indication so far whether France intends to substitute for the U.S. nuclear umbrella or the forward-deployed dual-capable aircraft in Europe. Unlike the United Kingdom—which is largely reliant upon the United States for its delivery systems and warhead designs and closely coordinates on nuclear war planning—France maintains a high degree of nuclear independence from its allies, which France calls “strategic autonomy” (Tertrais 2020).

France does not have a no-first-use policy and reserves the right to conduct a “final warning” limited nuclear strike to signal to an adversary that they have crossed a line—or to signal the French resolve to conduct further nuclear strikes if necessary—in an attempt to “reestablish deterrence” (Élysée 2020; Tertrais 2020). Although France is a member of NATO, its nuclear forces are not part of the alliance’s integrated military command structure. The Defense Ministry’s 2013 White Paper says the French nuclear deterrent “ensures, permanently, our independence of decision-making and our freedom of action within the framework of our international responsibilities, including in the event of any threat of blackmail that might be directed against us in the event of a crisis” (French Ministry of Defense 2013). In 2020, President Macron explained that, if an aggressor is not deterred, France’s “nuclear forces are capable of inflicting absolutely unacceptable damages upon that state’s centers of power: its political, economic and military nerve centers” (Élysée 2020). For a more in-depth examination of the evolution of France’s nuclear doctrine, see Bruno Tertrais’ authoritative report, “French Nuclear Deterrence Policy, Forces and Doctrine” (Tertrais 2020).

During a French parliamentary hearing on January 11, 2023, Gen. Thierry Burkhard, the French Chief of Defence, further explained France’s nuclear doctrine:

[Our deterrent] is not articulated around the notion of threshold, because it would allow our adversaries to maneuver around in conscience and circumvent our deterrence ‘from the bottom up.’ Our deterrence capability guarantees second-strike possibilities through the redundancy of resources and the invulnerability of the sea-based leg. The possibility of using the nuclear weapon first is assumed: our doctrine is neither that of no first use nor that of the sole purpose, according to which nuclear weapons are only addressed to the nuclear threat… Nuclear deterrence does not seek to win a war or prevent losing one. (Burkhard 2023; our translation)

Nuclear exercises

France’s Strategic Air Forces, Forces Aériennes Stratégiques (FAS), conduct approximately 70 exercises per year, four of which are called “Operation Poker,” an exercise designed to train and demonstrate the capability of France’s airborne deterrent, four times a year. The “Poker” exercise involves a majority of France’s nuclear-capable Rafale aircraft, which during flights carry unarmed air-sol moyenne portée-amélioré (ASMPA) air-launched cruise missiles (Air & Cosmos International 2022; Service de l’Information Aéronautique 2022) (see Figure 2). During the exercise, the FAS carries out a simulated nuclear air raid on an enemy target, including refueling operations by Phénix tankers and penetration of enemy airspace and firing of ASMPA missiles by Rafale fighters (MAF 2024d).

A Rafale BF3 practices alert in a protective aircraft shelter at an unknown base (potentially Saint Dizier) with an ASMPA nuclear cruise missile shape attached to its center pylon. (Photo: French Air Force).

The Poker flight exercise is sometimes preceded by a nuclear loading exercise known as “Operation Banco.” The Strategic Air Force has for many years publicly referred to the combined exercises as “Operation Banco, Poker.” In a hearing before the French parliament in June 2019, then-commander of the Strategic Air Force Gen. Bruno Maigret detailed the nuclear weapons loading operation:

“[A]lmost all of the nuclear warheads are removed and mounted on Rafale aircraft at nuclear-capable bases, as if the President of the Republic had given us the order to ramp up. The exercise ends when the crews reach the onboard alert stage, ready to power up and take off, often after a week spent in underground positions waiting for the order. At this point, the nuclear weapons are detached, and we move on to Operation Poker—the tip of the iceberg.” (Assemblée Nationale 2019)

The most recent iteration of Operation Poker took place on March 25, 2025—the first time France has conducted the operation in daytime since April 2021 (Powis 2025).

Command, control, and communication

France maintains strict and centralized control over its nuclear arsenal, with the president having sole and final authority as to the decision to use nuclear weapons. However, in practice, the implementation of such a decision would involve additional military personnel—namely the highest- and second-highest-ranking military officers: the Chef d’État-Major des Armées (CEMA) and the Chef de l’État-Major Particulier du Président de la République (CEMP), who is the president’s top military advisor.

Only one of those officials—the CEMA—is enshrined in the French defense code as the responsible official for ensuring that the president’s order is executed (Légifrance 2025). However, conflicting accounts appear to exist regarding the CEMP’s role, with testimony reportedly indicating that under previous administrations, the president and the CEMP each carried one half of the nuclear codes (Pelopidas 2019; Wellerstein 2019).

The primary command post for the president to transmit nuclear orders is called “Jupiter” and is located underneath the Élysée Palace (Dryef 2020). A mobile command post travels with the president at all times (French Department of Legal and Administrative Information 2017). This command post links and authenticates the president with the CEMA, who is tasked with disseminating the order down to the individual launch units through the secure RAMSES (Réseau Amont Maillé Stratégique et de Survie, translated as “upstream strategic and survival mesh network”) network. In the event of a massive nuclear strike against France, orders can be transmitted through SYDEREC (Système de Dernier Recours, translated as “system of last resort”) (Tertrais 2010).

The nuclear command center for the air component of the French deterrent is known as the Centre Opérationnel des Forces Aeriennes Strategiques (COFAS) nuclear operations center and is located underground at Taverny Air Base (BA-921) north of Paris.

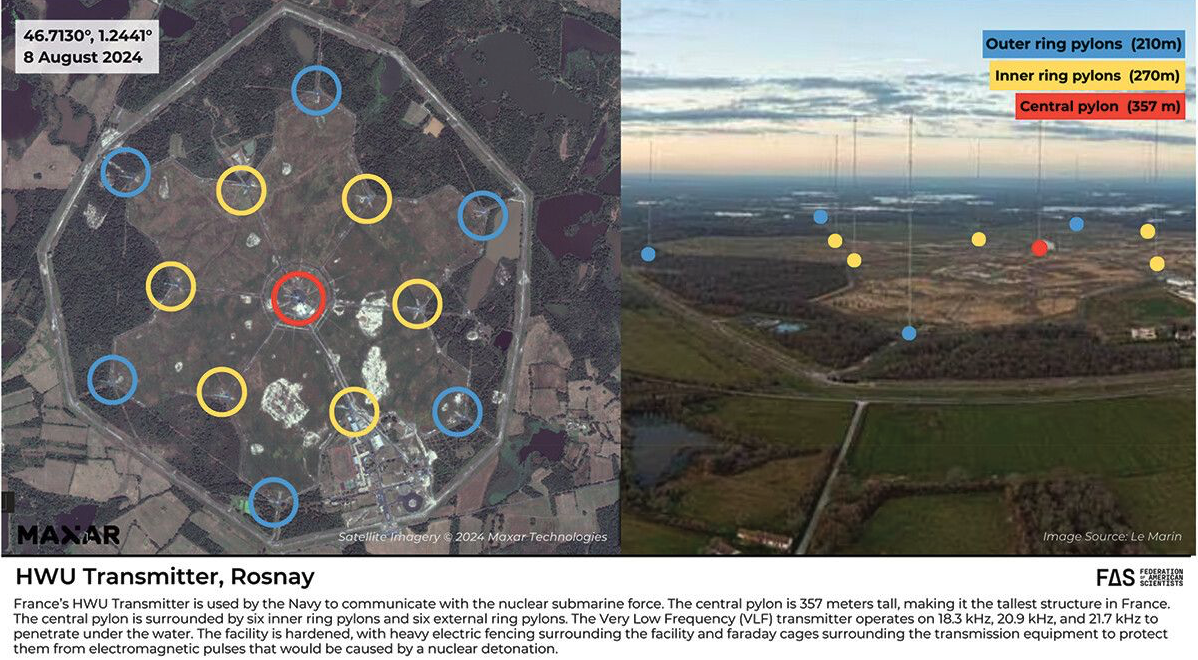

Communication with deployed ballistic missile submarines at sea is facilitated by a network of very-low frequency radio transmitting stations, including locations in Rosnay, La Régine, Kerlouan, and Saint-Assise (see Figure 3). These stations host antennas that are among the tallest structures in France, with the central pylon being taller than the Eiffel Tower.

Submarine-launched ballistic missiles

The French force of submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) constitutes the backbone of the French nuclear deterrent. Under the command of the Strategic Ocean Force (Force Océanique Stratégique, or FOST), the French Navy (Marine Nationale) operates four Triomphant-class nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) equipped with nuclear-armed long-range ballistic missiles—Le Triomphant (hull number S616), Le Téméraire (S617), Le Vigilant (S618), and Le Terrible (S619).

Each submarine can carry a set of 16 M51-type SLBMs, but since one boat is always undergoing routine maintenance, France has only produced 48 SLBMs—enough missiles to equip each of France’s three operational SSBNs. France typically test-launches its SLBMs from two locations: on land at DGA Essais de Missiles near Biscarrosse, and at sea near the same site. The most recent test of the M51 SLBM was the first qualification test firing for the M51.3 that took place on November 18, 2023 (MAF 2023).

Like the other Western nuclear powers, the French Navy maintains a continuous at-sea deterrent posture with at least one boat on patrol, one preparing for patrol, one returning to port, and one in maintenance. Each submarine patrol lasts on average approximately 70 days. In March 2022, the French Navy temporarily deployed more than one SSBN for the first time since the 1980s, likely in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (Newdick 2022). In early 2025, Le Monde reported that submariners stationed at Île Longue naval base had inadvertently exposed information about SSBN patrol schedules through sharing location data on the fitness app Strava (Bourdon and Schirer 2025). According to Le Monde’s investigation, the data was substantial enough to map out the operation schedules, and users had even created their profiles using their real names.

The SSBN force is based at the Île Longue naval base near Brest in Brittany, which includes two drydocks, nuclear warhead storage, and missile handling and storage facilities. The base used to include a unique set of what appeared to be 24 vertical silos for storing missiles that were not loaded on submarines; but most of these silos now appear to have been dismantled with only four remaining. The missile storage and maintenance site is located about four kilometers south of the base at the Guenvénez pyrotechnic site.

Over the past few years, several infrastructure upgrades have taken place at Île Longue that are visible through satellite imagery, including the construction of a new electrical plant and pumping station, as well as what appears to be a covered bunker enclosing a rail spur that connects to the SSBNs dry docks.

Long-term submarine repairs and refueling take place at the Brest naval base across the bay, which has three large drydocks (Naval Technology n.d.). The SSBNs are built and dismantled at the shipyard in Cherbourg.

France relocated its SSBN command center from Houilles in the Yvelines to the Île Longue base in 2000, while submarine communication facilities continue to operate using France’s HWU transmitter at Rosnay and possibly other locations. French SSBNs are protected during their operations by nuclear attack submarines, maritime patrol aircraft (such as Atlantique 2s), anti-submarine frigates, and minesweepers. The Atlantique 2 aircraft operate out of Lann-Bihoué Naval Air Base near Lorient.

The Dassault Atlantique 2 maritime patrol aircraft (MPA) is scheduled to be replaced by the Patmar (short for patrouille maritime) program in the 2030s. In early 2025, the Direction Générale de l’Armement, France’s defense procurement agency, signed a contract with Airbus Defence and Space to further evaluate the feasibility of its proposal for its A321MPA next-generation long-range MPA concept (Airbus 2025; Tringham 2025). According to the French Navy head of the Naval Air Office, Naval Staff—Plans/Program, the study is expected to conclude by mid-2026, at which point a final decision will be made on whether to move forward to the procurement phase (Tringham 2025).

All French SSBNs now carry the M51 SLBM, which was deployed starting in 2010 to gradually replace the M45 SLBM (Tran 2018). The last M45 was withdrawn from service in September 2016 (Assemblée Nationale 2023a). The M51 has reportedly been developed in close conjunction with the Ariane 5 space-launch vehicle, and the two share a number of technological commonalities, including solid-fueled heavy boosters, electronics, wiring, and guidance systems. The three-stage M51 reportedly has a range of over 6,000 kilometers and carries a liquid-propellant post-boost vehicle, allowing for the deployment of multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs) and penetration aids (Tertrais 2020; Willett 2018).

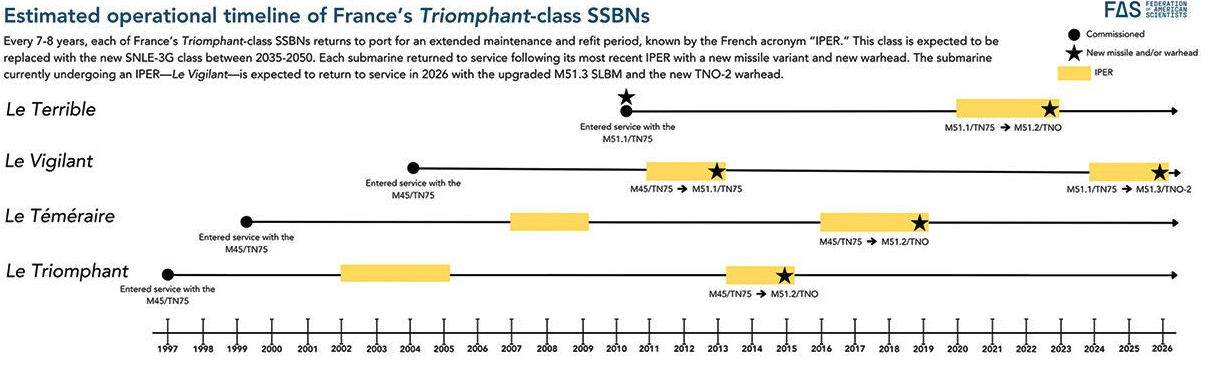

The M51 is undergoing continuous iteration (see Figure 4): The first version—the M51.1—had improved range and accuracy over the M45 and could carry up to six 100-kiloton TN75 MIRV warheads. The second version, known as M51.2, was reportedly commissioned in 2016 (Assemblée Nationale 2023a; Parly 2017) and is “capable of far greater range” than the predecessor (possibly more than 9,000 kilometers), according to the French Ministry of Defense, and carries a new warhead—the tête nucléaire océanique, or TNO. The TNO is reportedly stealthier than the TN75 and reportedly weighs about 230 kilograms, approximately double that of the TN75. It is unclear how many TNO warheads the M51.2 SLBM can carry, but it is suspected that some missiles have been downloaded to carry fewer warheads to increase targeting flexibility in limited scenarios (Tertrais 2020, 57). As of 2024, three of France’s four submarines had been upgraded to the M51.2 version carrying the TNO; French nuclear officials stated that the TN75 remained in service with the M51.1 missile as recently as January 2023 (Assemblée Nationale 2023b)—but has since been retired.

Based on these and other comments from French officials and the refit schedule of France’s four submarines, it is believed that the final submarine to upgrade from the M51.1/TN75 is Le Vigilant (see Figure 5). At the end of 2023, Le Vigilant began its multi-year extended maintenance period, known in French as “Indisponibilité pour Entretien et Réparations,” or IPER, with its older missiles and warheads presumably offloaded at Île Longue before it was tugged across the bay to a dry-dock at Brest naval base in January 2024 (Groizeleau 2024). As a result, the M51.1 SLBM and associated TN75 warhead appear to have been retired from active service and the warheads transitioned out of the stockpile for dismantlement at Valduc.

Official documents state that a new version of the M51 is planned to be deployed every ten years (Assemblée Nationale 2024). Therefore, a third iteration of the missile—the M51.3, which began development in 2014—is scheduled for commissioning into service by the end of 2025 (Assemblée Nationale 2024). This missile will incorporate a new third stage for extended range and further improvement in accuracy and will carry a new “adapted oceanic warhead,” the TNO-2 (Assemblée Nationale 2023b, 2024; Parly 2017). The first submarine to receive the new M51.3 SLBM with the modified TNO-2 warhead will likely be Le Vigilant, which is scheduled to complete its IPER in 2026.

Given that the Triomphant-class SSBNs are expected to reach the end of their operational lives in the 2030s, the third-generation nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine (sous-marin nucléaire lanceur d’engins de 3ème generation or SNLE-3 G) program was officially started in 2021 (Assemblée Nationale 2023a). The steel cutting for the first SSBN took place in Cherbourg in March 2024, with plans for it to begin entering operational service around 2035 (MAF 2024b; Scott 2024). With a planned delivery rate of one submarine every five years, the last fourth and final submarine will be delivered in 2050 (Assemblée Nationale 2024). The SNLE-3 G will incorporate a longer hull and advanced stealth features and will initially be equipped with the incoming M51.3 SLBM (Assemblée Nationale 2023b; Mills 2020, 11; Vavasseur 2018) but later upgraded to the fourth iteration of the M51—the M51.4 (Assemblée Nationale 2023b).

Air-launched cruise missiles

The second leg of France’s nuclear arsenal consists of nuclear ASMPA (air-sol moyenne portée-amélioré) air-launched cruise missiles for delivery by fighter-bombers operated by the Strategic Air Forces and the Naval Nuclear Aviation Force. The bombers assigned to the nuclear mission also serve conventional missions.

The Strategic Air Forces (Forces Aériennes Stratégiques or FAS) operate approximately 40 nuclear-capable Rafale BF3 aircraft organized into two squadrons—the EC 1/4 “Gascogne” and EC 2/4 “La Fayette” at Saint-Dizier Air Base (Air Base 113) about 190 kilometers east of Paris (Pintat and Lorgeoux 2017). EC 2/4 previously operated nuclear-capable Mirage 2000Ns at Istres Air Base until June 21, 2018, when the aircraft was officially retired from the French Air Force. After the Mirage 2000N’s retirement, EC 2/4 moved from Istres to Saint-Dizier. Now, both squadrons operate Rafale BF3 twin-seat strike fighters, leaving the Rafale the sole aircraft responsible for France’s nuclear strike mission (French Ministry of Defense 2018; Jennings 2018).

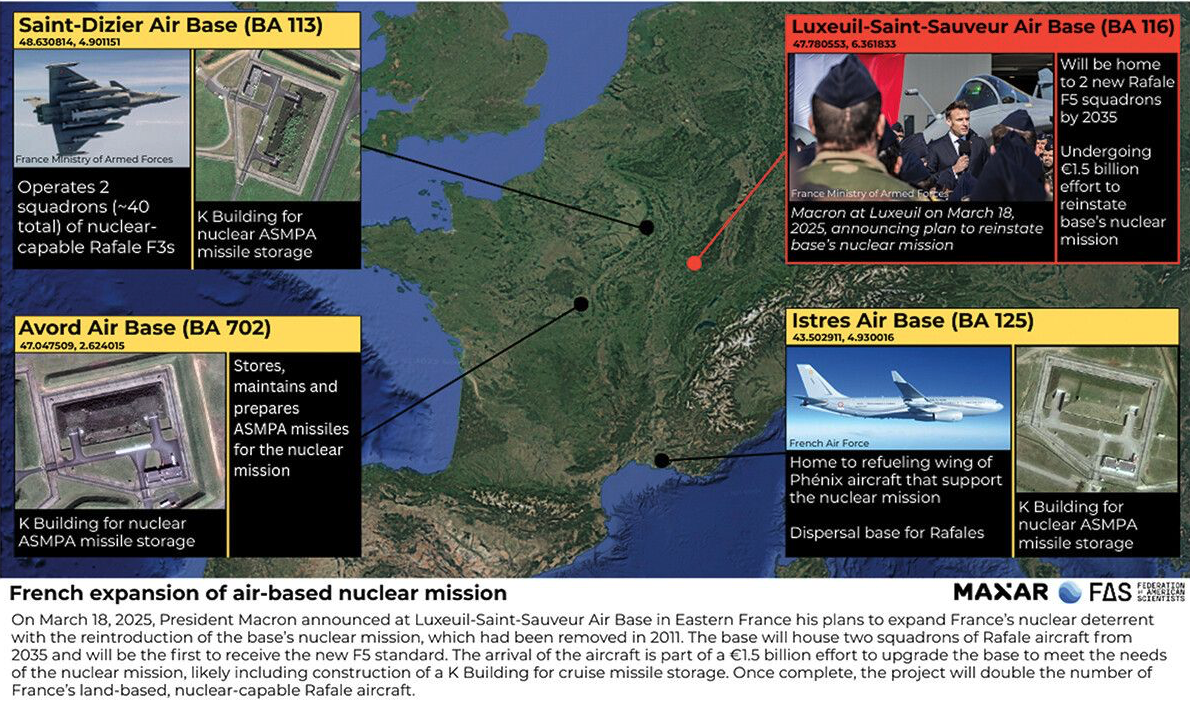

On March 18, 2025, during a visit to Luxeuil-Saint-Sauveur air base (Air Base 116) in eastern France, President Macron announced plans to reactivate the base’s nuclear mission with the introduction of two squadrons of Rafale aircraft by 2035 (see Figure 6). Luxeuil lost the nuclear mission in 2011 when the EC 2/4 squadron was moved to Istres air base. The reactivation of the nuclear mission at Luxeuil is part of a €1.5 billion ($1.7 billion) modernization plan. Luxeuil will become the first base to receive the next-generation Rafale F5 and the future ASNG4 hypersonic nuclear missile (Vincent 2025; MAF 2025; Élysée 2025). Once complete, this project will double the number of France’s nuclear-capable Rafale aircraft.

France’s Minister of the Armed Forces, Sébastien Lecornu, announced the development of a new F5 standard of the Rafale aircraft via his official X account on October 9, 2024. “The modernization of the Rafale to the F5 standard will be a revolution for the conventional missions of our armies and for our nuclear deterrence,” his post read (Lecornu 2024). The new aircraft are expected to be delivered beginning in 2030 and will be accompanied by a “loyal wingman” stealth combat drone designed for reconnaissance and penetration operations beginning in 2033 (Charpentreau 2024; Dassault 2025). The drones will be operated directly from the cockpit of the Rafale aircraft (MAF 2024a).

The F5 standard will emphasize suppression of enemy air defense capabilities via upgraded avionics and the ability to carry the future air-to-surface hypersonic nuclear missile currently under development, the ASN4G (Dassault 2025; Satam 2024). During his visit to Luxeuil on March 18, President Macron announced that he would “increase and accelerate Rafale orders,” prompting a follow-on announcement by the head of Dassault Aviation, Rafale’s manufacturer, that the company was working to increase production from the current output of approximately two aircraft per month to four aircraft per month by 2028 (RFI 2025).

The Naval Nuclear Aviation Force (Force Aéronavale Nucléaire or FANu) operates at least one squadron (11F and possibly 12F) with 10 Rafale Marine (MF3) aircraft for nuclear strike missions onboard France’s sole aircraft carrier, the Charles de Gaulle (Tertrais 2020, 58). The French carrier is the only surface ship in NATO equipped to carry nuclear weapons. The FANu and its ASMPA missiles are not permanently deployed onboard the carrier but can be rapidly deployed by the president in support of nuclear operations (Kristensen 2009; Pintat and Lorgeoux 2017). While the Charles de Gaulle’s home port is Toulon on the Mediterranean coast, the aircraft are based at the Landivisiau Naval Aviation Base in northern France. The nuclear ASMPA missiles earmarked for deployment on the carrier are thought to be co-located with ASMPAs belonging to the Strategic Air Forces at either Avord Air Base or Istres Air Base—or possibly at both.

The ASMPA, which has a range of up to 500 kilometers, first entered service in 2009 and has completely replaced the older ASMP. France produced a total of 54 ASMPAs, including those needed for flight testing. In 2016, France launched a mid-life refurbishment program designed to maintain the missile into the 2030s (Mills 2020, 10; Scott 2022). The life-extended version is known as “air-sol moyenne portée-amélioré rénové,” or ASMPA-R, and will be equipped with the same warhead as the ASMPA, the tête nucléaire aéroportée (TNA). The missile’s producer, MBDA, says the warhead has a “medium energy” yield, possibly similar to the yield of the TNO (Kristensen 2015; MBDA n.d.). The first firing of the ASMPA-R was conducted in December 2020, and after a successful qualification firing in March 2022, France approved the upgraded missile’s serial production and refurbishment (Assemblée Nationale 2023a, Direction Générale de l’Armement 2022; Scott 2022). On May 22, 2024, the Strategic Air Forces conducted the missile’s first evaluation launch from a Rafale, which the Air and Space Force declared a success (lair 2024). Interestingly, France blurred the missile in all official images of the test launch that have been released.

The French Ministry of the Armed Forces is also developing a successor to the ASMPA-R: a fourth-generation air-to-surface nuclear missile (a ir-sol nucléaire de 4ème génération, ASN4G) with enhanced stealth and maneuverability that is scheduled to reach initial operational capability in 2035 and remain in service beyond the 2050s (Assemblée Nationale 2023a). The missile will incorporate new hypersonic technologies to enable its maneuverability at high speeds (Assemblée Nationale 2023b). France’s Rafale aircraft are also being modernized, with plans for an “all Rafale” air fleet by 2035 (Élysée 2023; Jennings 2021; MAF 2022, 41). When the ASN4G missiles become operational, they will be carried by the Rafale F5s currently under development (Assemblée Nationale 2023a). Ten to 15 years later, the ASN4G will be integrated onto France’s next-generation fighter jet, which is expected to replace the Rafale (Assemblée Nationale 2023b).

Until 2009, the management and storage of France’s air-launched nuclear weapons was conducted by the Dépôts-Ateliers de Munitions Spéciales(DAMS) located at Saint-Dizier, Istres, and Avord Air Bases. In 2009, these three bases were adapted for ASMPA storage and the high-security nuclear weapons storage facility upgraded and renamed as “K Buildings” (Tertrais 2020). Although nuclear-capable Rafales operated by the Strategic Air Forces are all located at Saint-Dizier, all three bases serve as dispersal and storage sites. Moreover, Avord or Istres—or both—are thought to serve as storage sites for the ASMPAs assigned to the Charles de Gaulle aircraft carrier for the Naval Nuclear Aviation Force strike mission. In June 2024, the Strategic Air Forces completed the consolidation of all FAS command headquarters units to Taverny Air Base in northern France (MAF 2024c). Given the Rafales’ relatively short range, France’s air-launched nuclear weapons capability depends on a support fleet of refueling aircraft. France previously operated a mixed fleet of Boeing C-135FR and KC-135R tanker aircraft but completed the replacement of the old tankers in September 2023 with the new Airbus A330-200 “Phénix” Multi-Role Tanker Transport (MRTT) aircraft (Janes 2023). As of October 2023, France had received 12 MRTTs from Airbus, with three more set to undergo conversion to the MRTT standard before being delivered to France, for an eventual fleet of 15 tankers (Airbus 2023).

At the October 2022 Euronaval exhibition, the French Armament General Directorate (DGA) revealed the latest design of the new generation aircraft carrier (Porte-Avions Nouvelle Génération, or PA-NG), which is expected to begin sea trials by 2037 and replace the Charles de Gaulle by 2038 (Peruzzi 2022; Saballa 2022). After some setbacks, France and Germany have also proceeded with their joint development of a sixth-generation combat aircraft that could potentially be nuclear-capable (Airbus n.d.; Sprenger 2018; Vincent and Bezat 2022).

The nuclear weapons complex

France’s nuclear weapons complex is managed by the Direction des Applications Militaires (DAM), a department within the Nuclear Energy Commission (Commissariat à l’énergie atomique et aux énergies renouvelables, or CEA). DAM is responsible for research, design, manufacture, operational maintenance, and dismantlement of nuclear warheads.

Warhead design and simulation takes place at the DAM center in Bruyères-le-Châtel, about 30 kilometers south of Paris. The center houses the Tera 1000—Europe’s most powerful supercomputer with a 25-petaflop capacity (one petaflop means one thousand million million operations per second)—and employs about half the people affiliated with the military section of the Nuclear Energy Commission (CEA 2016).

The Commission’s Valduc Center, about 30 kilometers northwest of Dijon, is responsible for nuclear warhead production, maintenance, storage, and dismantlement. The site has recently expanded because of the 2010 French-British Teutates Treaty, an agreement to collaborate on technology associated with the two countries’ respective nuclear weapons stockpiles. The Epure facility at Valduc includes three high-power radiographic axes, including the AIRIX X-ray generator, which will “make it possible to characterize, to the highest level of precision, the state and hydrodynamic behavior of materials, under the conditions encountered in the pre-nuclear phase of weapon functioning,” as the Nuclear Energy Commission said in its 2017 annual report (CEA 2017, 4; Teutates n.d.). This function is critical to maintaining and developing France’s nuclear weapons in the absence of live nuclear test explosions. Significant additional upgrades are underway at Valduc.

Finally, the Nuclear Energy Commission’s CESTA (Centre d’Études Scientifiques et Techniques d’Aquitaine) near Le Barp, about 30 kilometers southwest of Bordeaux, is responsible for designing equipment for nuclear weapons and reentry vehicles, as well as coordinating the development of nuclear warheads. The Laser Mégajoule (LMJ), France’s equivalent to the U.S. National Ignition Facility, is located at the same site. Construction on the LMJ began in 2005, and LMJ started conducting its first experiments in 2014 (CEA 2016). The facility is designed to validate theoretical models of nuclear weapons detonations and, therefore, plays an important role in France’s nuclear simulation program.

France previously produced tritium using two dedicated reactors at the Marcoule Nuclear Site located about 30 kilometers north of Avignon, which were shut down in 2009 (Glaser 2011, 7). In 2024, France’s Minister of the Armed Forces announced plans to produce tritium for nuclear weapons at the civilian Civaux nuclear power plant in central France (International Panel on Fissile Materials 2024; Cristofari 2024; Roche-Bayard 2025). The decision to use a civilian nuclear power plant to produce tritium for nuclear weapons is a first for France, although it is similar to what the United States does.

Hans M. Kristensen, Matt Korda, Eliana Johns, Mackenzie Knight-Boyle

The authors wish to thank Allie Maloney, the Herbert Scoville Jr. Peace Fellow for the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists, for her invaluable assistance with background research, analysis, and generation of graphics for this publication.

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the Jubitz Family Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares, the Prospect Hill Foundation, and individual donors.

References:

- 2020 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons. 2022. “National Report Pursuant to Actions 5, 20 and 21 of the Final Document of the 2010 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons: 2015—2022.” Report submitted by France, NPT/CONF.2020/42/Rev.1, August 1. https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/npt_conf.2020_42_rev.1_advance.pdf

- Airbus. 2023. “Airbus Signs € 1.2 Billion in Contracts for Capability Enhancement and in-Service Support of the French A330 MRTT Fleet.” October 23. https://www.airbus.com/en/newsroom/press-releases/2023-10-airbus-signs-eu-12-billion-in-contracts-for-capability-enhancement

- Airbus. 2025. “Airbus Signs New Study Contract to Define France’s Future Maritime Patrol Aircraft.” February 4. https://www.airbus.com/en/newsroom/press-releases/2025-02-airbus-signs-new-study-contract-to-define-frances-future-maritime

- Airbus. n.d. “Future Combat Air System (FCAS): Shaping the Future of Air Power.” https://www.airbus.com/en/products-services/defence/multi-domain-superiority/future-combat-air-system-fcas

- Air & Cosmos International. 2022. “Poker 2022-04: Strategic Air Raid Simulation for the French Air and Space Force.” December 14. https://aircosmosinternational.com/article/poker-2022-04-strategic-air-raid-simulation-for-the-french-air-and-space-force-3428

- Assemblée, Nationale. 2019. “Compte rendu de réunion n° 43—Commission de la défense nationale et des forces armées.” June 12, https://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/dyn/15/comptes-rendus/cion_def/l15cion_def1819043_compte-rendu

- Assemblée, Nationale. 2023a. Information Report Compiling the Hearings of the Committee on Nuclear Deterrence. April 24. https://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/dyn/16/rapports/cion_def/l16b1112_rapport-information

- Assemblée, Nationale. 2023b. Tome VII—Défense : Équipement des forces—Dissuasion. October 30. https://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/dyn/17/rapports/cion_def/l17b0527-tvii_rapport-avis

- Assemblée, Nationale. 2024. Tome VII—Défense : Équipement des forces—Dissuasion. October 30.

- Bourdon, S., and A. Schirer. 2025. “StravaLeaks: Dates of French Nuclear Submarine Patrols Revealed by Careless Crew Members.” Le Monde, January 13. https://www.lemonde.fr/en/videos/article/2025/01/13/stravaleaks-dates-of-french-nuclear-submarine-patrols-revealed-by-careless-crew-members_6737005_108.html

- Burkhard, T. 2023. “General, Chief of the Defense Staff. Statement Before the National Defense and Armed Forces Commission.” January 11.

- CEA (Commissariat à l’énergie atomique et aux énergies alternatives). 2016. Annual Report 2016. http://www.cea.fr/english/Documents/corporate-publications/annual-report-cea-2016.pdf

- CEA (Commissariat à l’énergie atomique et aux énergies alternatives). 2017. Annual Report 2017. https://www.cea.fr/english/Documents/corporate-publications/cea-annual-report2017.pdf

- Charpentreau, C. 2024. “Dassault nEUROn to fly again, driving France’s new combat drone development.” AeroTime. December 5. https://www.aerotime.aero/articles/dassault-neuron-combat-drone-loyal-wingman

- Cooper, A. R. 2022. “A New Window into France’s Nuclear History.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. September 16. https://thebulletin.org/2022/09/a-new-window-into-frances-nuclear-history/

- Dassault, Aviation. 2025. “Annual Report: 2024.” March 5. https://www.dassault-aviation.com/wp-content/blogs.dir/2/files/2025/04/AR_2024_VA_BD.pdf

- Deleaz, T., and B. Hue. 2018. “Google Maps va flouter les prisons françaises d’ici décembre.” RTL. October 9. https://www.rtl.fr/actu/politique/pas-normal-que-les-prisons-ne-soient-pas-floutees-par-google-juge-nicole-belloubet-sur-rtl-7795106325

- Dryef, Z. 2020. “Le « PC Jupiter », le bunker de l’Elysée qui abrite les conseils de défense.” Le Monde. November 6. https://www.lemonde.fr/m-le-mag/article/2020/11/06/le-pc-jupiter-refait-surface_6058787_4500055.html

- Élysée. 2020. “Speech of the President of the Republic on the Defense and Deterrence Strategy.” February 7. https://www.elysee.fr/en/emmanuel-macron/2020/02/07/speech-of-the-president-of-the-republic-on-the-defense-and-deterrence-strategy

- Élysée. 2023. “Transforming Our Armed Forces: The President of the Republic Presents the New Military Programming Bill.” January 20. https://www.elysee.fr/emmanuel-macron/2023/01/20/transformer-nos-armees-le-president-de-la-republique-presente-le-nouveau-projet-de-loi-de-programmation-militaire

- Élysée. 2025. “Speech by the President of the Republic from Air Base 116 luxeuil-Saint-Sauveur.” March 18. https://www.elysee.fr/emmanuel-macron/2025/03/18/deplacement-sur-la-base-aerienne-116-de-luxeuil-saint-sauveur

- France TV. 2022. “L’événement avec Emmanuel Macron.” October 12. https://www.france.tv/france-2/l-evenement/4221058-avec-emmanuel-macron.html

- French Air and Space Force (@Armee_de_lair). 2024. “Aujourd’hui, l’@Armee_de_lair et les équipages des FAS ont réussi le premier tir d’évaluation des forces du missile ASMP-A rénové en coopération avec la @DGA. Une nouvelle démonstration de la crédibilité de la composante aéroportée de la dissuasion nucléaire.” Tweet. May 22. https://x.com/Armee_de_lair/status/1793315562937839740

- French Department of Legal and Administrative Information. 2017. “Comment le president de la République puet-il déclencher le ‘feu nucléaire’?” April 19. Accessed via the Wayback Machine. https://web.archive.org/web/20170517094723/http://www.vie-publique.fr/questions/comment-president-republique-peut-il-declencher-feu-nucleaire.html

- French Ministry of Defense. 2013. “White Paper on Defense and National Security 2013.” April 29. https://www.defense.gouv.fr/english/dgris/defence-policy/white-paper-2013/white-paper-2013

- French Ministry of Defense. 2018. ““La dissuasion aéroportée passe au tout Rafale” [Airborne Deterrence Passes to All Rafale].” Press Release, updated August 29 (updated September 29 (updated September 5)). https://www.defense.gouv.fr/air/actus-air/la-dissuasion-aeroportee-passe-au-tout-rafale

- Glaser, A. 2011. “Military Fissile Material Production and Stocks in France.” Princeton University. https://www.princeton.edu/~aglaser/PU057-Glaser-2011.pdf

- Granlund, J. 2025. “French Military Increases Presence: Nuclear Weapons Also Protect Sweden.” SVT Nyheter. April 24. https://www.svt.se/nyheter/lokalt/norrbotten/fransk-militar-okar-narvaron-karnvapnen-skyddar-aven-sverige

- Groizeleau, V. 2024. “Le SNLE Le Vigilant en cale sèche dans le cadre de sa nouvelle IPER.” Mer et Marine. https://www.meretmarine.com/fr/defense/le-snle-le-vigilant-en-cale-seche-dans-le-cadre-de-sa-nouvelle-iper

- International Panel on Fissile Materials. 2024. “France to Produce Tritium for Nuclear Weapons in EDF Civilian Nuclear Reactors.” March 18. https://fissilematerials.org/blog/2024/03/france_to_produce_tritium.html

- Jennings, G. 2018. “France Retires Mirage 2000N Nuclear Bomber.” Jane’s Defence Weekly. June 25. https://janes.ihs.com/Janes/Display/FG_961954-JDW

- Jennings, G. 2021. “France Begins Rafale F4 Flight Trials.” Janes. May 21. https://www.janes.com/defence-news/news-detail/france-begins-rafale-f4-flight-trials

- Kristensen, H. 2009. “French Aircraft Carrier Sails without Nukes.” Federation of American Scientists. August 4. https://fas.org/blogs/security/2009/08/degaulle/

- Kristensen, H. 2015. “France,’ In Assuring Destruction Forever: 2015 Edition.” Reaching Critical Will. April. http://www.reachingcriticalwill.org/images/documents/Publications/modernization/france-2015.pdf

- Lecornu, S. 2024. “La modernisation du Rafale au standard F5 sera une révolution pour les missions conventionnelles de nos armées et pour notre dissuasion nucléaire.” X. October 9. https://x.com/SebLecornu/status/1843979886018572714

- Légifrance. 2008. “LAW No. 2008-696 of July 15, 2008 Relating to Archives.” July 16. https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/jorf/article_jo/JORFARTI000019198568

- Légifrance. 2025. “Code de la défense.” Section 1 : Préparation et mise en œuvre des forces nucléaires (Articles R*1411-1 à R*1411-6): Version en vigueur au 05 mai 2025. https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/codes/id/LEGISCTA000021047922

- MAF (French Ministry of the Armed Forces). 2022. Projet de loi de finances: Année 2023” [ Finance Bill: Year 2023]. MAF: Paris. September. https://www.defense.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/ministere-armees/Projet%20de%20loi%20de%20finances%20-%202023%20-%20LPM%20ann%C3%A9e%205.pdf

- MAF (French Ministry of the Armed Forces). 2023. “Succès d’un tir d’essai de missile M51.” MAF: Paris. November 18. https://www.defense.gouv.fr/dga/actualites/succes-dun-tir-dessai-missile-m51

- MAF (French Ministry of the Armed Forces). 2024b. “Lancement de la construction du premier sous-marin nucléaire lanceur d’engins de 3e generation.” March 20. https://www.defense.gouv.fr/dga/actualites/lancement-construction-du-premier-marin-nucleaire-lanceur-dengins-3e-generation

- MAF (French Ministry of the Armed Forces). 2024c. “Les Forces aériennes stratégiques, piliers de la dissuasion nationale.” October 17. https://www.defense.gouv.fr/actualites/forces-aeriennes-strategiques-piliers-dissuasion-nationale

- MAF (French Ministry of the Armed Forces). 2024d. “Opération Poker réussie pour les Forces aériennes stratégiques.” December 19. https://www.defense.gouv.fr/air/actualites/operation-poker-reussie-forces-aeriennes-strategiques

- MAF (French Ministry of the Armed Forces). 2025. “Retour de la dissuasion nucléaire à Luxeuil-Saint-Sauveur.” March 19. https://www.defense.gouv.fr/air/actualites/retour-dissuasion-nucleaire-luxeuil-saint-sauveur

- MAF (French Ministry of the Armed Forces: @Armees_Gouv). 2024a. “Sur la base aérienne 113 de Saint-Dizier pour les 60 ans des Forces aériennes stratégiques, @SebLecornu annonce une évolution majeure pour la dissuasion nucléaire aéroportée française : le nouveau standard du Rafale, le F5, qui emportera le futur missile nucléaire ASN4G. Le ministre a également annoncé le lancement du programme de drone de combat furtif, qui sera opéré directement depuis le cockpit du Rafale.” Tweet. October 8. https://x.com/Armees_Gouv/status/1843646555657478369

- Maitre, E. 2025. “The French Nuclear Deterrent in a Changing Strategic Environment.” Fondation pour la Recherche Stratégique. FRS note No. 4. March 11. https://www.frstrategie.org/sites/default/files/documents/publications/notes/2025/042025.pdf

- MBDA. n.d. “ASMPA: Air-To-Ground Missile, Medium Range, Enhanced.” Fact Sheet. https://www.mbda-systems.com/?action=force-download-attachment&attachment_id=5253

- Mills, C. 2020. “The French Nuclear Deterrent.” House of Commons Library, Briefing Paper Number 4079, November 20. https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN04079/SN04079.pdf

- Naval Technology. n.d. “L’Île Longue Submarine Base.” https://www.naval-technology.com/projects/lilelonguesubmarineb/

- Newdick, T. 2022. “France Has Increased Its Ballistic Missile Submarine Patrols for the First Time in Decades.” The Drive. March 24. https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/France-has-increased-its-ballistic-missile-submarine-patrols-for-the-first-time-in-decades

- Parly, F. 2017. “Madame Florence Parly, Ministre des armées, Visite de L’usine des Mureaux: Ariane Group” [Florence Parly, Minister of the Armed Forces, Visit to the Mureaux Factory: Ariane Group].” French Ministry of the Armed Forces, Mureaux. December 14. https://www.vie-publique.fr/discours/204491-declaration-de-mme-florence-parly-ministre-des-armees-sur-lentreprise

- Pelopidas, B. 2019. France: Nuclear command, Control, and Communications. NAPSNet Special Report. Nautilus Institute. June 10. https://nautilus.org/napsnet/napsnet-special-reports/france-nuclear-command-control-and-communications/

- Peruzzi, L. 2022. “French Navy New Generation Aircraft Carrier Design Detailed.” European Defense Review. December 13. https://www.edrmagazine.eu/french-navy-new-generation-aircraft-carrier-design-detailed

- Pintat, X., and J. Lorgeoux. 2017. “Rapport d’information fait au nom de la commission ds affaires étrangères, de la défense et des forces armées par le groupe de travail « La modernisation de la dissuasion nucléaire’.” Sénat Rapport N 560. May 23. https://www.senat.fr/rap/r16-560/r16-5601.pdf

- Powis, G. 2025. “Poker 2025-01 : rarissime exercice aérien nucléaire majeur sur la France aux premières lueurs du jour.” Air & Cosmos. March 25. https://air-cosmos.com/article/poker-2025-01-rarissime-exercice-aerien-nucleaire-majeur-sur-la-france-aux-premieres-lueurs-du-jour-70065

- RFI. 2025. “France’s Dassault Says Stepping Up Rafale Warplane Output.” March 24. https://www.rfi.fr/en/france/20250324-france-s-dassault-says-stepping-up-rafale-warplane-output

- Roche-Bayard. 2025. “Vienna: Civaux Power Plant Ready for Military Nuclear Power.” La Nouvelle République. February 6. https://www.lanouvellerepublique.fr/vienne/commune/civaux/vienne-la-centrale-de-civaux-est-prete-pour-le-nucleaire-militaire-1738854523

- Saballa, J. 2022. “France Unveils nuclear-Powered Aircraft Carrier.” The Defense Post. October 21. https://www.thedefensepost.com/2022/10/21/france-nuclear-powered-aircraft-carrier/

- Sarkozy, N. 2008. “Presentation of ‘Le Terrible’ Submarine.” Cherbourg. March 21. https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/Speech_by_Nicolas_Sarkozy presentation_of_Le_Terrible_submarine.pdf

- Satam, P. 2024. “France Announces Development of Rafale F5 with New UCAV and Nuclear Missile.” The Aviationist. October 10. https://theaviationist.com/2024/10/10/development-of-rafale-f5-with-new-ucav-and-nuclear-missile/

- Scott, R. 2022. “Successful Flight Test of Upgraded ASMPA Missile Paves Way for Refurbishment.” Janes. March 30. https://www.janes.com/defence-news/news-detail/successful-flight-test-of-upgraded-asmpa-missile-paves-way-for-refurbishment

- Scott, R. 2024. First Steel Cut for French SNLE 3G Deterrent Submarine.” Janes. March 21. https://www.janes.com/osint-insights/defence-news/sea/first-steel-cut-for-french-snle-3g-deterrent-submarine

- Service de l’Information Aéronautique 2022. “Carte Global des Zones Poker.” SUP AIP 261/22, November 24, via Air & Cosmos International. https://aircosmosinternational.com/media/3532/download

- Sprenger, S. 2018. “Germany, France to Move Ahead on sixth-Generation Combat Aircraft.” Defense News. April 6. https://www.defensenews.com/2018/04/06/germany-france-to-move-ahead-on-sixth-generation-combat-aircraft/

- Tertrais, B. 2010. France, in “Governing the Bomb: Civilian Control and Democratic Accountability of Nuclear Weapons.” In Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, edited by H. Born, B. Gill, and H. Hänggi, 103—127. Stockholm: SIPRI. https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2018-10/sipri10gtb.pdf

- Tertrais, B. 2020. “French Nuclear Deterrence Policy, Forces and Future: A Handbook.” Fondation pour la Récherche Stratégique. February. https://www.frstrategie.org/sites/default/files/documents/publications/recherches-et-documents/2020/202004.pdf

- Teutates. n.d. “The French/UK Joint Facility Epure.” French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission. https://www-teutates.cea.fr/uk/joint-facility-epure.html

- Tran, P. 2018. “France Makes Progress on Refitting Submarine for M51 Missiles.” Defense News. July 23. https://www.defensenews.com/naval/2018/07/23/france-makes-progress-on-refitting-submarine-for-m51-missiles/

- Tringham, K. 2025. “French Navy’s Future MPA Replacement Programme Moves to Next Phase.” Janes. February 3. https://www.janes.com/osint-insights/defence-news/sea/french-navys-future-mpa-replacement-programme-moves-to-next-phase

- Vavasseur, X. 2018. “Here is the First Image of the French Navy Next Generation SSBN—SNLE 3G.” Navy Recognition. October 3. http://www.navyrecognition.com/index.php/news/defence-news/2018/october-2018-navy-naval-defense-news/6538-here-is-the-first-image-of-the-french-navy-next-generation-ssbn-snle-3g.html

- Vincent, E. 2025. “Macron Announces Establishment of Fourth Nuclear Air Base in France.” Le Monde. March 19. https://www.lemonde.fr/en/france/article/2025/03/19/macron-announces-establishment-fourth-nuclear-air-base-in-france_6739324_7.html

- Vincent, E., and J. Bezat. 2022. “France and Germany Find Agreement on FCAS Warplane Development Deal.” Le Monde. November 20. https://www.lemonde.fr/en/economy/article/2022/11/20/france-and-germany-announce-fcas-warplane-development-deal_6004930_19.html

- Wellerstein, A. 2019. “NC3 decision-Making: Individual versus Group Process.” Tech4GS Special Reports. August 8. https://securityandtechnology.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/wellerstein_commander_nc3_IST_report.pdf

- Willett, L. 2018. “Ballistic Trajectory: French SLBM Technology Developments Boost Operational Output.” Jane’s International Defence Review. September 25. https://janes.ihs.com/Janes/Display/FG_1080227-IDR