President Donald Trump has quietly authorized the Pentagon to carry out military operations against what his administration calls “narco-terrorist” networks in Latin America. On paper, it’s a counter-narcotics policy. In practice, it serves as a green light for open-ended U.S. military action abroad, bypassing congressional approval, sidestepping international law, and stretching the definition of “national security” until it becomes a catch-all justification for the use of force.

The directive allows the U.S. to target groups unilaterally labeled as both criminal and terrorist. Once that designation is made, the military can operate without the consent of the targeted country, a move that violates international law. In a region with a long history of U.S.-backed coups, covert wars, and destabilization campaigns, the risk of abuse isn’t hypothetical; it’s inevitable.

While the order applies across Latin America, Venezuela stands at the top of the list. The Trump administration has accused President Nicolás Maduro’s government of working with transnational cartels, and has doubled the bounty on him to $50 million (double the bounty for Osama bin Laden). It’s a lawfare tactic designed to criminalize a head of state and invite mercenaries and covert operatives to participate in regime change. The accusations fueling this escalation have grown increasingly far-fetched casting Maduro in turn as a partner of Colombia’s FARC, the head of the “Cartel de los Soles,” a patron of Venezuela’s Tren de Aragua, and now, as an ally of Mexico’s Sinaloa Cartel–a charge even Mexico’s own president says has no evidence, revealing how politicized and unfounded this allegation is.

The core premise of the accusation is that Maduro is involved in a cocaine trafficking network of Venezuelan military and political figures called Cartel de los Soles. The Venezuelan government denies the cartel’s existence, calling it a fabrication to justify sanctions and regime change efforts. Multiple independent investigations have shown no hard evidence exists and that this narrative thrives in a media—intelligence echo chamber. Reports from outlets like Insight Crime cite anonymous U.S. sources; those media stories are then cited by policymakers and think tanks, and the cycle repeats until speculation becomes policy.

Fulton Armstrong, a professor at American University and a former longtime U.S. intelligence officer, has stated that he knows no one in the intelligence community, apart from those currently in government, who believes in the existence of the Cartel de los Soles.

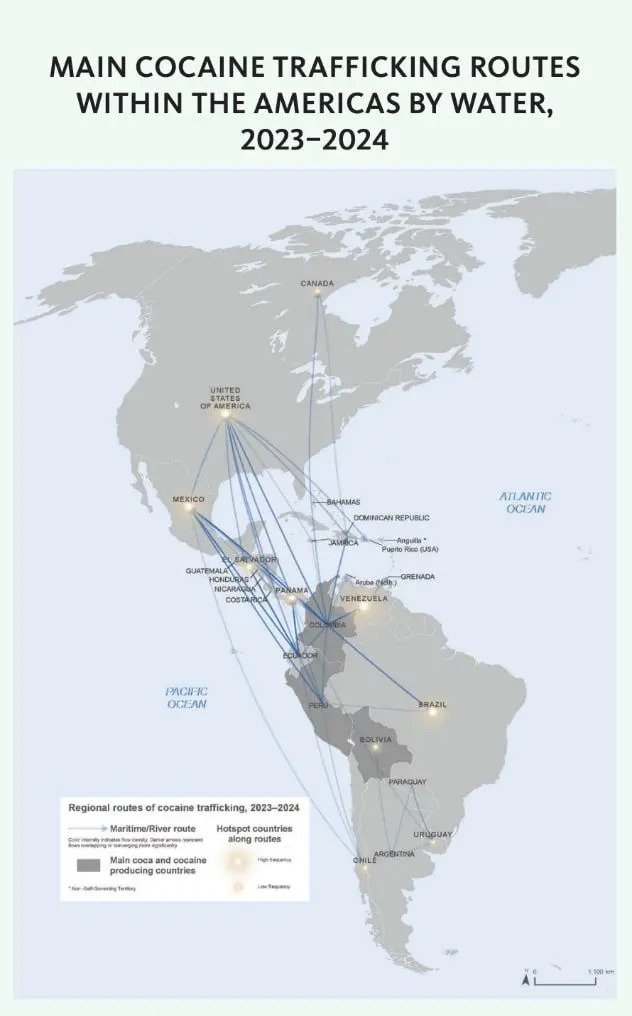

Drug monitoring data also contradict this narrative. The Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA) reports that only about 7 percent of U.S.-bound cocaine transits through the Eastern Caribbean via Venezuela, while approximately 90 percent takes Western Caribbean and Eastern Pacific routes. UNODC’s 2025 World Drug Report likewise confirms that trafficking remains concentrated in major Andean corridors, not through Venezuela. Yet Venezuela is targeted anyway, not for its actual role in the drug trade, but because neutralizing its government has become a pillar of U.S. foreign policy, seen in Washington as a step toward reshaping the country’s political system and prying open its economy to foreign control.

The “narco-terror” label put on Venezuela also attempts to rope Venezuela into the U.S. fentanyl crisis, despite the absence of evidence that the country plays any role in fentanyl trafficking. Even U.S. own drug enforcement assessments make no mention of Venezuela as a source or transit point.

This link exists only in political rhetoric, a way to fold Venezuela into a domestic public health crisis and recycle the same logic used to brand it a “national security threat.” That accusation dates back to 2015 when President Obama created the legal and political scaffolding for an open-ended campaign of coercion. Once the “narco-terror” framework is in place, Washington can sustain and escalate military measures over time, regardless of the immediate pretext.

This framing turns a political standoff into a declared security imperative. It broadens the range of permissible military tools, from ISR (intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance) to direct action.

The pattern is familiar. In Panama (1989), Colombia (2000s), and Honduras (2010s), U.S. militarized anti-drug campaigns failed to dismantle supply chains or reduce trafficking volumes. What they did accomplish was shifting routes, militarizing criminal actors, and destabilizing governments, making the original problems harder to solve and the affected societies more fragile.

The Mirror at Home: Militarization and Communities of Color

The same militarized logic driving U.S. policy in Venezuela is being applied inside the United States. In August 2025, President Trump signed an executive order placing the D.C. Metropolitan Police Department under federal control and deployed the National Guard, citing a public safety “emergency,” despite official data showing violent crime at multi-year lows. Even U.S. law enforcement statistics contradict the White House narrative, but the administration dismissed them, casting the city as overrun by “roving mobs,” “wild youth,” and “drugged-out maniacs.”

D.C. is only one example. The same militarized logic has sent thousands of troops to the U.S.-Mexico border, converted military bases into detention centers from Texas to New Jersey, and stationed soldiers inside ICE detention facilities in over 20 states. In Los Angeles, Marines and National Guard units patrolled immigrant neighborhoods in a show of force, a deployment beaten back only by mass community resistance and the threat of labor action.

Whether it’s a wall in the desert or barricades in front of the White House, the message is the same: perceived threats, real or manufactured, are met with troops, not talks. The playbook never changes: In Venezuela, the “threat” is cast as narco-terrorism; in the U.S., it’s a “border surge” or a manufactured public safety emergency built on racially coded depictions of Black and Brown communities. In both cases, the logic is identical: treat political disputes and social crises as security emergencies, sideline diplomacy and community solutions, usurp greater executive powers, and make military force a routine tool of governance.

The Real Threat

Trump’s “narco-terror” authorization uses the language of fighting drugs and crime to mask a deeper project: expanding the military’s role in governance and normalizing its use as a tool of political control both at home and abroad.

In Latin America, that means more interventions against governments the U.S. wants to topple. At home, it means embedding the military deeper into civilian life, particularly in Black and Brown neighborhoods.

The communities in Caracas and Los Angeles, in the Venezuelan plains, and in the U.S.-Mexico border may seem worlds apart, but they are facing the same war machine. Until we reject militarization in all its forms, the targets will keep shifting, but the people under the gun will look the same.

Michelle Ellner is a Latin America campaign coordinator of CODEPINK. She was born in Venezuela and holds a bachelor’s degree in languages and international affairs from the University La Sorbonne Paris IV, in Paris. After graduating, she worked for an international scholarship program out of offices in Caracas and Paris and was sent to Haiti, Cuba, The Gambia, and other countries for the purpose of evaluating and selecting applicants.