Introduction

The polarizing nature of the Black Power Movement captured the attention of the entire nation. The revolutionary rhetoric espoused by prominent Black organizations and activists also earned the full attention of intelligence agencies in the United States hell-bent on quelling any support of socialist economic practices at the height of the Cold War. Covert operations like the FBI’s infamous Counterintelligence Program (COINTELPRO) identified, surveilled, defamed, and often murdered Black leaders they deemed capable of leading an organized rebellion against the U.S. government. The rise of radical organizations like the Black Panther Party produced a counterculture that encouraged cultural pride and collective uplift and ultimately rejected the notion that European cultural practices were superior. Songs like “What’s Going On?” by Marvin Gaye, “Say it Loud” by James Brown, and “Young, Gifted, and Black” by Nina Simone would influence the generation that went on to create Hip-Hop. This influence was evident in artists like Public Enemy and Tupac Shakur. Despite assassinating, incarcerating, or exiling nearly every prominent leader of the Black Power Movement, the federal government’s fears of a Black Messiah never subsided. This paper will trace the history of surveillance of Black artists who began to use their music to push political agendas. This paper will also explore how various American institutions engaged in a cultural war and how several law enforcement agencies continued the practices of COINTELPRO to neutralize Black musicians who had the potential to be political leaders.

In Blues People: Negro Music in White America, Amiri Baraka suggests that music is a living organism and in many ways he is correct.1 From the work songs sung by enslaved Africans to the rap music crooned by the dispossessed Black youth of the contemporary moment, Black music has always reflected the social and political moment in which Black musicians created the music. “Cultural change is guided by material change.”2 In this context, the music produced by Africans in America has always been political to a certain extent. Music has represented a safe space in which Black people could express their feelings about their material conditions in a creative way. The evolution from work songs and folk spirituals to blues, jazz, and beyond was not by chance but instead a result of an ever-shifting socio-political and economic landscape in the United States. This evolution is evident in the work songs sung by enslaved Africans. According to Baraka, it was common practice to sing while working in West Africa. However, the difference was the work songs in West Africa referenced the ownership of the land they labored on. The lyrical content of the work songs chanted by enslaved Africans changed drastically due to the alienated relationship the enslaved had with the land they were forced to work and live on.3

In Liner Notes for the Revolution: The Intellectual Life of Black Feminist Sound, Daphne Brooks posits that Black music is a type of intellectual labor that is “inextricably linked to the matter of Black life.”4 This is most apparent during the twentieth century as Black culture began to be absorbed into the mainstream cultural consciousness. Not only did Black people begin to gain more access to the mainstream political arena, but Black artists gained more autonomy in their respective mediums. This was more evident in Black music than any other artistic expression, especially soul music and later, hip-hop and rap music. The music being produced at this time was a space for a creative articulation of political desires as well as a record of what Black life was like at the time the music was recorded.

In Party Music: The Inside Story of the Black Panthers’ Band and How Black Power Transformed Soul Music, Rickey Vincent investigates how the cultural workers in the Black Power Movement and the pioneers of the sonic revolution of Soul music influenced each other. Vincent explores the intersection of politics and culture by focusing on the setlist of a band called “The Lumpen” at a Black Panther-sponsored concert in Oakland in November 1970. At the behest of the Minister of Culture, Emory Douglas, ordinary members of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense (BPP) formed a soul group with the goal of reaching Black youth to recruit them to the party. These revolutionary musicians remixed popular soul music with lyrics saturated with revolutionary rhetoric to broaden the audience exposed to their message. Leaders within the BPP recognized as Stokeley Carmichael said “from the spirituals right on up, music would be our weapon and our solace.”5 The BPP’s soul band gave them the power to circulate the ideals and ideologies of the Black Power Movement through the popular culture of the moment. The material conditions of Black life shaped the cultural production of the historical movement of “The Lumpen” and continue to do so in the contemporary moment.

Much like most Black artists at the time, The Lumpen existed at the intersection of politics and culture. From the songs they decided to reinterpret, to their lyrics and band name, everything was intentionally deeply political and held the BPP party line. The band’s name is a spin on lumpenproletariat, a term coined by German philosopher Karl Marx. Marx described the lumpenproletariat as the “social scum refuse of all classes” or individuals who participated in the unsanctioned economy such as sex workers, drug dealers, and houseless people. According to Marx, this class of people had no significant use in a working-class revolution and often utilized lumpenproletariat as a pejorative term in his work. However, the BPP believed the lumpenproletariat had the potential to be the vanguard of a social and political revolution and would lead Black people to liberation. By naming themselves “The Lumpen” they simultaneously reclaimed and rebranded a word from one that described the undesirables of society to people who are talented, intelligent, and perhaps most importantly, that revolutionaries can be soul brothers too. Black Panther Party leadership concluded that in order to reach the masses of Africans in America their messaging needed to be culturally relevant as well as politically progressive. Vincent argues that the selection of songs The Lumpen decided to remix and perform was exceptionally intentional. The artists they covered not only had mass crossover appeal but were known for promoting racial pride and uplift.

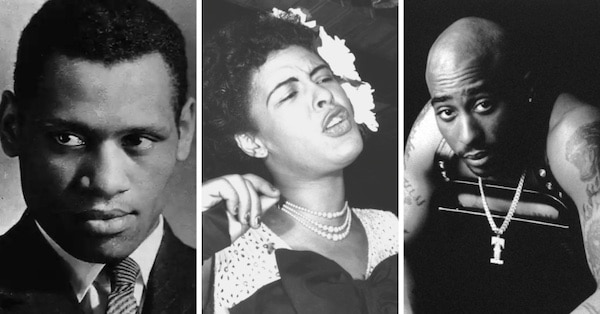

Although The Lumpen gained enough popularity to go on a college tour, they were never chart-topping musicians with an audience reaching all demographics in the United States and globally. They also weren’t the first Black artists to use their musical talents and large platform to disseminate a political message or show solidarity to social movements. However, the desire to mix politics and music has always come at a price for Black musicians in the United States. Black artists often receive the same treatment as leaders of mass social movements if they decide to delve into the world of politics with their music. From Paul Robeson to Billie Holiday and later Tupac Shakur the general public and the United States government have a history of showing hostility and attempting to discredit musicians who politicize their music to speak to the sociopolitical moment.

Historian Rickey Vincent states that “All social movements have utilized the celebratory music of the masses and aligned them with the politics of pleasure in order to unify their group members.”6 The Black Protest Music Tradition uses lyrics to convey “implied meanings and coded messages of resistance.”7 These double meanings in songs speak to the Black masses in ways only they can understand while still being accepted by mainstream culture. This music spoke to a common experience but was also deeply personal. Protest music serves as direct social commentary and a weapon to combat an oppressive capitalist political economy. As Harold Cruse asserted: “No social movement of a protest nature… can be successful or have any positive meaning unless it is at one and the same time a political, economic, and cultural movement.”8 Oftentimes, Black musicians are unable to express their political beliefs without the restrictions of a European-American dominated industry that pressures them to compromise, sanitize and depoliticize their ideas for the sake of selling records. Even if an artist is at the apex of their respective career if they do not retreat from making protest music they risk losing their careers.

Paul Robeson and the Red Scare

One of the first recorded examples of an artist that was persecuted for articulating his political beliefs in his music is Paul Robeson. Born April 9th, 1898 in Princeton, New Jersey, and the youngest of five, Robeson’s upbringing influenced his worldview and the decisions he would make throughout his career. Robeson’s father, William Drew Robeson, was a formerly enslaved person and became a Reverend in the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church shortly after escaping to freedom through the Underground Railroad.9 The Reverend was a pillar in the community Robeson was raised in and was known for being an advocate for causes impacting the Black community. According to Robeson, his father emphasized to him and his siblings that “the Negro was in every way the equal of the white man. And we fiercely resolved to prove it.”10

The values of personal integrity, generosity, and loyalty to one’s convictions were paramount in the Robeson household. For the Robeson’s, maintaining personal integrity means that one would strive to reach “maximum human fulfillment.” Robeson asserts that “success in life was not to be measured in terms of money and personal advancement, but rather the goal must be the richest and highest development of one’s own personal development11.” The determination to reach one’s full potential was evident in Robeson’s dedication to his craft the entertainer and activist learned over twenty-five languages to make his work accessible to the widest audience possible.12 Due to the high expectations set by his father, Robeson excelled in nearly every endeavor he embarked on. He was an exceptional student-athlete in high school and earned a scholarship at Rutgers University. Robeson’s time at Rutgers was filled with adversity, his teammates tried to kill him during his first practice as a member of the football team causing several serious injuries. Instead of quitting the team, he went on to be named to the All-American team. Academically, Robeson was named valedictorian of his class at Rutgers and went on to earn a Law Degree from Columbia University. Despite excelling as a scholar and athlete, Robeson decided to pursue a career in entertainment.

Robeson rose to stardom by playing lead roles in The Emperor Jones and Othello in the mid-1920s and his fame only grew after performing the same roles in the film adaptations. Robeson was also in high demand as a singer due to his renditions of spirituals, traditional folk songs, and political protest songs.13 The influence of Robeson’s upbringing in the AME church was evident in the ways he performed his music. According to Historian Sterling Stuckey, “Robeson’s roots were established in a religion that reveals African influences through musical creativity that allows virtually no break between the sacred and the secular.”14 The music being played in AME churches Robeson grew up in contained the seeds that would bloom into blues and jazz.

Robeson toured the world for nearly two decades, from his rise to stardom in the mid-1920s through the 1940s; as a result, his politics began to shift towards a more internationalist orientation. He also became a staunch advocate for decolonial efforts taking place throughout Africa and was a close friend of Jomo Kenyatta, the first president of independent Kenya. Robeson recognized that his fame and notoriety provided him the ability to disseminate political messages and ideas and “had a potentially deeper impact than merely speaking for a cause.”15 Robeson’s willingness to embrace socialism as a viable economic system that could be useful to African struggles on the continent and in the United States made him a target to the U.S. government.

In 1947, Robeson announced his plans to temporarily retire from the stage. During his hiatus from the spotlight, Robeson stated he wanted to “enter this struggle, for what I call getting into the rank and file of my people, for full citizenship in these United States.”16 The next few years, he “marched up and down the nation to protest the oppression of Blacks.” Robeson’s celebrity status and his budding potential as a political leader of a mass movement triggered a cause for concern for leaders in the U.S. government.17 Despite being a person of interest to the United States Intelligence apparatus, Robeson continued his audacious quest for justice and equality. Robeson spoke at events, performed at union halls and rallies, and wrote several articles and essays about the plight of Africans in America. Robeson’s cosmopolitan sensibilities also influenced his political views, although he championed the rights of Africans in the U.S. and abroad, he advocated for the liberation of all oppressed groups and working-class unity. The U.S. is generally wary of people who rise to prominence by challenging the status quo however, his willingness to embrace alternative modes of production such as socialism is what made him public enemy number one. More specifically Robeson’s admiration of the Soviet Union and the remarks he made at the 1949 Paris Peace Conference were the death knells to his career. In April 1949, Robeson was invited to Paris to perform at the Soviet-sponsored Peace conference. According to American author Gilbert King, Robeson performed “Joe Hill” a ballad written about a union leader unjustly imprisoned for murder in 1915, and gave a short speech after singing. This speech would have dire consequences for Robeson’s professional career and led to him being forced into obscurity by mainstream media. According to King, Robeson’s speech was not unlike any of his previous speeches, he spoke about the African struggle for freedom in the United States. He also spoke in opposition to the possibility of a third world war and asserted that the general public in the U.S. did not want another war.18 Oddly enough, the transcript of Robeson’s speech was transmitted back to the United States by the Associated Press before he even took the stage and his message was misrepresented. Associated Press suggested that Paul Robeson declared that Africans in America would not fight in a war against the Soviet Union. Robeson went from the most revered African man in the United States to being nicknamed “the Kremlin’s voice of America” by a witness during a hearing held by Senator Joseph McCarthy’s House of Un-American Activities (HUAC).19

Robeson’s admiration for the Soviet Union was due to their socialist economic models that “in less than twenty years, had brought many formerly ‘backward’ people of color into the scientific/industrial world of the twentieth century.” Robeson also argued that the rise of the Soviet Union could be helpful and “an important factor in aiding the colonial liberation movement” in Africa.20 When asked about his visit to the USSR during a tour stop, Robeson stated “I have spoken many times about my first trip to the Soviet Union in 1934. For the first time as I stepped on Soviet soil, I felt myself a full human being.”21 As the Cold War intensified in the late 1940s and many feared the possibility of World War III, McCarthyism, and anti-communism was running rampant throughout the United States. To garner support for the arms war against the Cold War, the federal government declared an all-out war against people who were suspected of having communist ties.

A consequence of the illogical hysteria of the Red Scare was countless people who may have been socialist but had no official ties to the Soviet Union were blacklisted in their respective careers. Unfortunately, Robeson’s stardom did not make him immune to McCarthyism. His salary dropped from $100,000 a year to less than $6,000 a year and remained there for the better part of a decade. His passport was revoked and was largely shunned by his peers in the entertainment industry.22 Shortly after his performance at the Paris Peace Conference, the HUAC called Jackie Robinson to the stand and Robinson publicly denounced Robeson’s misrepresented comments and by extension distanced himself from Robeson as well. This is indicative of how the rest of the Black bourgeoisie treated Robeson for the duration of his life. Because the attacks were more so geared towards Robeson’s political beliefs and activities rather than his race, it was more difficult to garner sympathy for what was happening to him and there is no record of Black celebrities showing solidarity to Robeson in any substantial way. The HUAC was one of the most powerful government institutions in the country during the 1940s and fifties. The entities in opposition to Robeson held some of the most powerful positions in the country and struck fear in the hearts of most Black professionals, entertainers, and intellectuals. Being alienated by the Black elite only perpetuated the crusade against Robeson.

Despite being silenced for nearly a decade, Robeson never wavered from his personal convictions. When he died in 1976 his memorial read: “The artist must first elect to fight for freedom or for slavery. I have made my choice. I had no alternative.”23 Paul Robeson is one of the earliest recorded examples of a Black artist that used his fame and notoriety to bring about positive social change. His resolve and uncompromising principles are what made him such an exceptional person but would also expedite the demise of his career. Although ultimately it did not matter in Robeson’s case, It is important to note that Robeson did not take the plunge into activism until he was at the height of his career, which is a pattern that can be seen throughout history. Despite being one of the most famous Black people in the world in the early twentieth century, Robeson proved to be a cautionary tale to aspiring Black entertainers hoping to break into the mainstream. Robeson’s fall from grace was a message to all entertainers that they would be better off keeping their political beliefs private, or at the very least, sanitizing their message to make white audiences comfortable. The case of Paul Robeson is also indicative of how the U.S. government and intelligence agencies would take action against artists who used their platform to uplift political and social justice movements.

The Tragedy of Billie Holiday

Despite the United States’ history of repression towards politicized entertainers and musicians, the protest song tradition continued. While Robeson was fighting his battle for freedom of expression and political beliefs, Billie Holiday was making her mark in the American musical canon due to her performance of the song “Strange Fruit”. “Strange Fruit” was written by a little-known Jewish high school literature teacher, poet, and militant communist named Abel Meeropol who went by the pen name Lewis Allan.24 Meeropol was inspired to write “Strange Fruit” in 1930 after seeing a postcard with the image of two Black men hanging from a tree after a lynching. Haunted by this image, Meeropol felt the need to act but was shocked to discover that six out of ten Euro-Americans approved of lynching at the time.25 Racial terrorism wreaked havoc throughout the United States immediately following Reconstruction and as a result, approximately 3,600 Black men, women, and children were lynched from 1889-1960.26 The fruit of Meeropol’s labor created a social commentary on race relations in America that would stand the test of time.

While the Black Protest Music Tradition historically used double meanings to convey the message to the song’s target audience, the explicit lyrics of “Strange Fruit” were a distinct divergence from this practice.

Southern trees bear a strange fruit,

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root,

Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze,

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.27

Although the graphic references to the deplorable conditions Africans lived in at the time indubitably captured the attention of the nation, it was Holiday’s delivery that cemented the song in American history. Holiday’s positionality and lived experiences as a Black woman in America gave her a deep connection to the emotions that were conveyed in the music.

Holiday was born Eleanora Faganin Baltimore, Maryland in 1915 to two young parents. Her father Clarence Holloway, was 13, and her mother, Sadie Fagan, was 14. The two met at a school dance and were never in a serious relationship. Holloway was a jazz musician and worked at local bars and clubs, her mother, Fagan, worked in domestic labor and was a prostitute.28 Her parents’ inability to properly care for her left her in the hands of her abusive aunt who did very little to protect Holiday. Holiday suffered abuse, neglect, and rape and by the time she was 13, she was forced into prostitution by her mother. Holiday’s lack of guidance led to several run-ins with the law and by the age of 15, she left Baltimore for Harlem.

Her move to Harlem proved to be pivotal for Holiday’s life and career; three years after her arrival, she captured the attention of a Columbia record producer. Holiday soon catapulted to fame and worked with jazz legends Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Count Basie, and several others.29 Much like Robeson, Holiday was at the apex of her career when she decided to take an explicitly political stance in her music. However, one stark difference between Robeson and Holiday’s case was that “Strange Fruit” created a paradox for Holiday. It simultaneously cemented her legacy as a jazz legend while also being a source of extreme vitriol from her white audiences. When her record label finally allowed her to record the song she became a target of law enforcement agencies almost immediately. The Federal Bureau of Narcotics was aware of Holiday’s drug use and although this was an open secret prior to the release of “Strange Fruit” she was scrutinized and criminalized for her drug use after the release of the iconic track. Holiday was accused of having communist sympathies and was swept up in McCarthy’s Red Scare. At the time of her premature death in 1959, her reputation had been defamed to the extent that she was looked back on as a drug addict rather than the ground-breaking vocalist she was. Robeson and Holiday stretched the boundaries of what Black artists could be capable of, beyond being brilliant musicians they showed a willingness to speak on behalf of an oppressed nation.

Holiday and Robeson laid the groundwork for what it meant to be an artist-activist.

As soul music emerged as one of the most popular genres amongst Black people, the Black Protest Music Tradition continued. As radical political organizations like the Black Panthers, the Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM), and leaders such as Malcolm X and Kwame Ture rose to prominence a revolutionary counterculture began to take shape. Artists like James Brown, Nina Simone, and Curtis Mayfield produced music that engendered feelings of racial pride and provided biting critiques of the sociopolitical terrain in America. In many ways, James Brown’s on-stage bravado coupled with his ad-libbed music over percussion-heavy tunes created the blueprint for the next generation’s hip-hop artists. When the era of the soul brother came to a close, a new youth movement took its place, rap groups like Public Enemy, Dead Prez, and N.W.A. provided a brash social commentary on the Black condition in the communities BPP and RAM had once served.

Tupac Shakur: “The Black Prince of the Revolution”

Just as the Black protest music tradition persisted, the state’s strategy to identify, surveilled, defame and repress artists who ventured into the political, continued. Music has evolved along with the material conditions of those creating it. As the deplorable conditions gave rise to the Black Power Movement persisted so did the need for a revolutionary political movement. One artist who attempted to fulfill that need was Tupac Amaru Shakur. Born on June 16th, 1971, Shakur was born into the struggle for Black liberation. His mother, Afeni Shakur was a leader in the New York Branch of the Black Panther Party and had just been acquitted on trumped-up conspiracy charges in the infamous Panther 21 Trial only one month prior to Tupac’s birth. Shakur was named after the last Incan leader to die fighting against Spanish colonizers and his mother lovingly called him the “Black Prince of the Revolution.”30 In addition to having a revolutionary for a mother, his godparents were Geronimo Pratt and Assata Shakur, who were also members of the BPP. Despite being the target of several brutal attacks by the United States Government, the Shakur family continued to dedicate their lives to the Black struggle.

Two years after being acquitted in the Panther 21 Trial, Afeni began dating Mutulu Shakur, a founder of the Republic of New Afrika (RNA).31 The RNA was an outgrowth of the Black Government Convention in Detroit, Michigan held in March 1968. Organized by Imari and Gaidi Obadele (formerly known as Richard and Milton Henry respectively), 500 activists came together to discuss the “destiny of the ‘captive Black nation’ in America”32 Influential Black nationalists such as Betty Shabazz, Amiri Baraka, and Queen Mother Moore were in attendance. At the conclusion of the Convention, dozens of attendees signed a document “declaring to the world that they would struggle for the complete independence and statehood of the Black nation.”33

The RNA would go on to create sister organizations to create mass support for their political objectives such as the New Afrikan People’s Organization (NAPO) and the New Afrikan Panthers. In 1984, Afeni moved the family to Baltimore and enrolled Tupac into The Baltimore School of the Arts, where he honed his acting, dancing, and writing skills for three years, the young artist also founded several activist organizations during this time.34 Afeni was also struggling with drug addiction at this time and as a result, Tupac had to live with her close friend Watani Tyehimba, for long periods of time, Tyehimba was a co-founder of NAPO. At their height, NAPO and the New Afrikan Panthers had chapters in ten cities across the country.35 Tupac regularly attended New Afrikan Panther meetings and they helped develop his political view and were the inspiration for him to start organizations while enrolled at The Baltimore School of the Arts. Shakur would eventually be voted president of the New Afrikan Panthers but relinquished his position once his acting career began to take off. However, he never waivered from his political beliefs and supported NAPO and the New Afrikan Panthers financially long after his rise to stardom.36 Shakur’s music career began to gain traction once his mother moved the family to California after a teen was murdered near their Baltimore home in 1987. Although it may be safe to assume that the surveillance of the Shakur family never ended, Tupac became a person of interest to the United States intelligence apparatus once his music became popular. As the rapper stated in a 1994 interview with MTV “I never had a record until I made a record.”37 Despite Tupac’s brash public persona and being depicted as a gangster by the mainstream media, the rapper never had any serious run-ins with the law prior to his rise to stardom. Although Tupac was already a rising star as an actor, what distinguished Shakur from Robeson and Holiday was that his music was political from the start. His whole persona as a rapper was carefully constructed with the goal of making the political objectives of NAPO and the New Afrikan Panthers mainstream. According to John Potash, author of The FBI War on Tupac Shakur: State Repression of Black Leaders from the Civil Rights Era to the 1990s this plan was motivated by the U.S. Intelligence apparatus to plot to assassinate the entertainer activist.

Devised in collaboration with his step-father, Mutulu Shakur, the “Thug Life Movement” was a plan with several objectives. However, the primary objective was to unify gangs across the country and orchestrate a truce between the Bloods and Crips. According to Potash, Tupac was to adopt a thuggish persona to appeal to gang members and then radicalize them and convince them to follow certain codes of conduct.38 This code of conduct would reduce Black victimization to street crimes and encourage gang members to seek legal avenues to generate income. Shakur also hoped to get gang members to realize who their oppressors were, and engage in revolutionary activity to upend the status quo. Although the FBI’s COINTELPRO was allegedly disbanded, law enforcement agencies employed the same practices the infamous program used to derail the Black Power Movement.

As Shakur’s “Thug Life” entered the mainstream, law enforcement agencies did everything in their power to prevent the rise of another Black Messiah. From the time of Tupac’s first album release “2pacalypse Now” in 1991 to his murder in 1996, the rapper survived three assassination attempts, specious lawsuits, and penal coercion. Prior to that five-year period, Tupac had never even been named a suspect in a crime.39

Shakur’s legacy being reduced to being a gangster rapper and someone constantly shrouded in controversy is not by accident. Similar to Robeson and Holiday, Shakur’s decision to venture into the political arena through music led to his image being defamed. Shakur’s work as an artist was prolific, but more importantly, he should be remembered as a revolutionary and a political theorist, and his life and ideas should be studied as seriously as those who came before him such as Huey P. Newton and Angela Davis.

Conclusion

Although the cases of Billie Holiday, Paul Robeson, and Tupac Shakur may seem like cautionary tales for musicians who may be inclined to politicize their lyrics they have served as an inspiration; especially Tupac. One of the most recent examples of the continuation of the Black Protest Music Tradition is YG and the late Nipsey Hussle’s “FDT.” On a surface level, the song was a manifestation of Tupac’s vision when he formulated the Thug Life Movement. A Blood and a Crip collaborated on a track to berate the newly elected president who rose to power by espousing racist, xenophobic, and sexist rhetoric.

Nearly fifty years after its creation, it is safe to say that hip-hop has entered the mainstream in the 21st century. As a new generation of activists emerges and tries to tackle the issues facing Africans in America, the power of music cannot be understated. History shows that political activists tend to be met with hostility, it is up to the masses to continue to support these artists when they are met with adversity. Cultivating a revolutionary culture is essential to bringing about political and social change. What better way to do that than with music?

Bibliography

Baraka, Imamu Amiri. Blues People: Negro Music in White America. New York, NY: Perennial, 2002.

Brooks, Daphne. Liner Notes for the Revolution: The Intellectual Life of Black Feminist Sound. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2021.

Carmichael, Stokely. Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture). New York, NY: Scribner, 2005.

King, Gilbert. “What Paul Robeson Said.” Smithsonian.com. Smithsonian Institution, September 13, 2011. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/what-paul-robeson-said-77742433/.

Potash, John L. The FBI War on Tupac Shakur: The State Repression of Black Leaders from the Civil Rights Era to the 1990s. Portland, OR: Microcosm Publishing, 2021.

Robeson, Paul. Here I Stand. Boston, Mass: Beacon Press, 1999.

Thuram, Lilian. “‘Southern Trees Bear a Strange Fruit.’” My Black Stars, 2021, 166–70. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1pfqnct.35.

Vincent, Rickey. Party Music: The Inside Story of the Black Panthers’ Band and How Black Power Transformed Soul Music. Chicago, IL: Lawrence Hill Books, 2013.

Notes:

- ↩ Imamu Amiri Baraka, Blues People: Negro Music in White America (New York, NY: Perennial, 2002), xi.

- ↩ Rickey Vincent, Party Music: The inside Story of the Black Panthers’ Band and How Black Power Transformed Soul Music (Chicago, IL: Lawrence Hill Books, 2013), xi.

- ↩ Imamu Amiri Baraka, Blues People: Negro Music in White America, 19.

- ↩ Daphne Brooks, Liner Notes for the Revolution: The Intellectual Life of Black Feminist Sound (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2021), 3.

- ↩ Stokely Carmichael with Ekwueme Michael Thelwell, Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture) (New York: Scribner, 2003), 529

- ↩ Vincent, Party Music: The inside Story of the Black Panthers’ Band and How Black Power Transformed Soul Music, 276.

- ↩ Ibid.

- ↩ Harold Cruse, The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual. (New York: Quill, 1984), 86.

- ↩ Paul Robeson, Here I Stand (Boston, Mass: Beacon Press, 1999), 6.

- ↩ Robeson, Here I Stand, 11.

- ↩ Robeson, Here I Stand, 18.

- ↩ Vincent, Party Music: The inside Story of the Black Panthers’ Band and How Black Power Transformed Soul Music, 268.

- ↩ Ibid.

- ↩ Robeson, Here I Stand, x.

- ↩ Vincent, Party Music: The inside Story of the Black Panthers’ Band and How Black Power Transformed Soul Music, 269.

- ↩ Vincent, Party Music: The inside Story of the Black Panthers’ Band and How Black Power Transformed Soul Music, 270.

- ↩ Robeson, Here I Stand, 72.

- ↩ Gilbert King, “What Paul Robeson Said,” Smithsonian.com (Smithsonian Institution, September 13, 2011), www.smithsonianmag.com

- ↩ Ibid.

- ↩ Robeson, Here I Stand, 83.

- ↩ Ibid.

- ↩ Robeson, Here I Stand, xviii.

- ↩ Vincent, Party Music: The inside Story of the Black Panthers’ Band and How Black Power Transformed Soul Music, 271

- ↩ Lilian Thuram, “‘Southern Trees Bear a Strange Fruit,’” My Black Stars, 2021, pp. 166-170, doi.org.

- ↩ Lilian Thuram, “‘Southern Trees Bear a Strange Fruit,’” 167.

- ↩ Ibid.

- ↩ Vincent, Party Music: The inside Story of the Black Panthers’ Band and How Black Power Transformed Soul Music, 273.

- ↩ Lilian Thuram, “‘Southern Trees Bear a Strange Fruit,’” 168.

- ↩ Lilian Thuram, “‘Southern Trees Bear a Strange Fruit,’” 169.

- ↩ John Potash, FBI War on Tupac Shakur: State Repression of Black Leaders from the Civil Rights Era to the 1990s (Portland, OR: Microcosm Publishing, 2021), 88.

- ↩ Potash, FBI War on Tupac Shakur: State Repression of Black Leaders from the Civil Rights Era to the 1990s, 89.

- ↩ Edward Onaci, Free the Land: The Republic of New Afrika and the Pursuit of a Black Nation-State (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2020), 1.

- ↩ Ibid.

- ↩ Potash, FBI War on Tupac Shakur: State Repression of Black Leaders from the Civil Rights Era to the 1990s, 103-104.

- ↩ Potash, FBI War on Tupac Shakur: State Repression of Black Leaders from the Civil Rights Era to the 1990s, 104.

- ↩ Potash, FBI War on Tupac Shakur: State Repression of Black Leaders from the Civil Rights Era to the 1990s, 14.

- ↩ Potash, FBI War on Tupac Shakur: State Repression of Black Leaders from the Civil Rights Era to the 1990s, 133.

- ↩ Potash, FBI War on Tupac Shakur: State Repression of Black Leaders from the Civil Rights Era to the 1990s, 125

- ↩ Potash, FBI War on Tupac Shakur: State Repression of Black Leaders from the Civil Rights Era to the 1990s, 186 Imamu Amiri Baraka, Blues People: Negro Music in White America (New York, NY: Perennial, 2002), xi.