September 13, is Political Prisoners Day.

“Ora Bhagat Singher bhai, ora Khudiramer bhai,

Samasta rajbandider mukti chai, mukti chai”(‘They are the brothers of Bhagat Singh, they are the brothers of Khudiram,

We want the freedom of all political prisoners’)— Popular Bengali song by Bipul Chakraborty

On September 13, 1929, Jatin Das, the 24-year-old revolutionary freedom fighter, died in Lahore Jail after a 63-day long hunger strike, demanding humane treatment of political prisoners under the British Raj.

The martyrdom of Jatin Das shook the entire country, and the journey of Jatin Das’ mortal remains by rail from Lahore to Kolkata was accompanied by a mass upsurge of people. The three and half kilometre long funeral procession in Kolkata was led by Subhas Chandra Bose, who described Jatin Das as the “young Dadhichi of India”, after the mythological sage who sacrificed his life for the common good.

Thus, September 13 is observed in India, especially by democratic rights organisations, as ‘Political Prisoners Day.’

Ironically, today when the country is observing the 75th anniversary of independence, which is being officially celebrated by the government as ‘Azadi ka Amrit Mahotsav’, thousands of people continue to linger in the jails as political prisoners.

Charged under British era laws such as sedition, or under post-independence anti-terror laws such as Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA), or under a variety of special security laws such as National Security Act, The Criminal Law Amendment Act, etc., the political prisoners of today carry the legacy of the freedom fighters who were imprisoned by the British.

Just as the British rulers used to refer to political prisoners during their rule as ‘terrorists’, the rulers of today also call people imprisoned for opposing them ‘terrorists’. And the mainstream media gleefully repeats and amplifies this, while paying lip service to the memory of the freedom fighters who were imprisoned by the British.

Political prisoners are considered ‘prisoners of conscience’, that is, people who have been imprisoned for activities which are not motivated by self interest but by the call of their conscience. One of the most important calls of conscience is to dissent against and oppose the actions of the state when it is considered to be unjust and oppressive.

This is what motivated the thousands of freedom fighters to oppose the British Raj, and who were imprisoned, tortured and executed by the British. Many were forced into exile as they would not submit to the government. We celebrate them today as heroes and martyrs, with the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party-Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh apparently most eager to do so in order to dominate the nationalist discourse while at the same time attempting to escape the stigma associated with not participating in the freedom struggle.

However, this does not stop the BJP government from arresting and imprisoning the dissenters of today, and over the last eight years we have seen numerous political activists, democratic rights activists, intellectuals, advocates, journalists, students, doctors, environmental activists and even comedians charged under such draconian laws and thrown into jail. Some have been able to get bail after a few months or years in jail while many have continued to languish there.

The only reason why these people have been imprisoned is that they have dissented against and opposed the policies of the government and have dared to speak the truth to power. They are the true successors of the legacy of the political prisoners of the British Raj, whom, including their ideological icon V.D. Savarkar, the BJP government appears to revere and celebrate.

The tactics of this government in imprisoning its political opponents and critics is strikingly similar to that followed by the British. For example, the British arrested and imprisoned a large number of revolutionaries in a few well-known so-called ‘conspiracy’ cases, such as the Meerut conspiracy case (1929) and the Kanpur conspiracy case (1924) and try to use them to demonise the entire revolutionary struggle for freedom.

The 16 arrested in connection with the Elgar Parishad case. One of them, Father Stan Swamy, passed away in custody. (Photo: The Wire)

The current government has similarly instituted cases like the Bhima Koregaon-Elgar Parishad case and the Delhi riots case to allege ‘conspiracies’ and thereby imprison a large number of activists and critics and demonise them as ‘anti-nationals’ and ‘terrorists’. The 16 activists, academics, advocates, journalists and cultural artistes (now 15, after the death of the 84-year-old Adivasi rights activist and Jesuit priest, Father Stan Swamy) arrested under the Elgar Parishad case, and activists such as Umar Khalid imprisoned under the Delhi riots case therefore carry the proud legacy of the political prisoners imprisoned under the Meerut and Kanpur conspiracy cases who were accused of seeking “to deprive the King Emperor of his sovereignty of British India, by complete separation of India from imperialistic Britain by a violent revolution”.

The only crime of the political prisoners of today is that they have opposed the policies and activities of the ‘King Emperor’ of ‘new India’ while ‘acche din (good days)’ have purportedly descended over the country.

While we know the names and remember some of the political prisoners such as the BK-16 and Umar Khalid, the problem of political incarceration of India is much larger.

Every state in India has numerous people imprisoned under laws such as UAPA or NSA or state security laws. In conflict zones such as Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand and Kashmir, many political prisoners are charged under provisions of the Indian Penal Code and Criminal Procedure Code, such as the Arms Act, Explosives Substances Act and Riot Act.

A vast majority of these unknown political prisoners are Adivasis, Dalits, Muslims and from other disadvantaged sections of society. Most of them spend years, and sometimes decades, in jail even before they undergo a trial. Communities such as the Adivasis, who faced the wrath of the British regime, when they resisted their dispossession and oppression in the hands of the British and their native lackeys, continue to face persecution by the state in independent India.

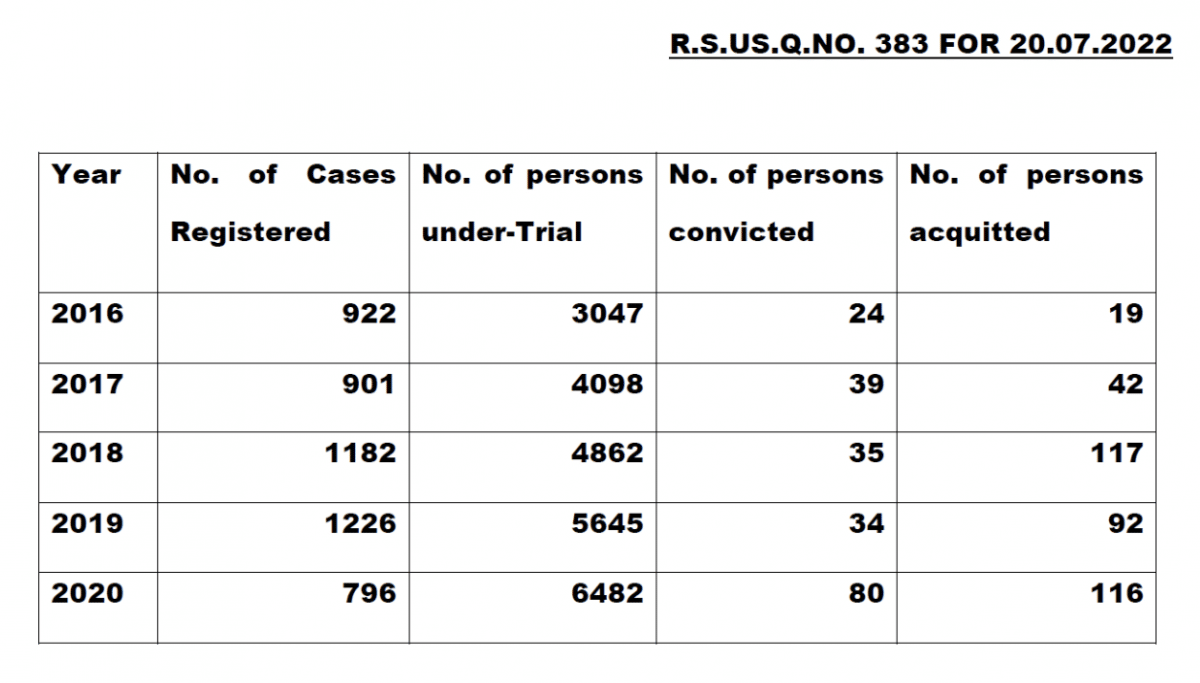

Therefore, Pandu Narote, a prisoner in Gadchiroli case imprisoned in Maharashtra who died in prison recently due to sheer medical negligence, or Ranjit Murmu, a prisoner held under UAPA who died in a West Bengal jail in 2011, carry the legacy of Birsha Munda or Sidhu-Kanhu, Adivasi fighters for freedom who were jailed and executed by the British. It is astounding to note, from the NCRB data as submitted by the Minister of State of Home Affairs in response to a parliamentary query on July 20, 2022, that there were 6,482 undertrial prisoners in India charged with UAPA in 2020.

This number has steadily increased since 2016, while the number of people actually convicted under the law has remained in double digits. That a country claiming to be a democracy, and celebrating the 75th year of its hard-won independence, can have more than 6,000 people imprisoned under a draconian act targeted at political opponents with the number increasing every year, says a lot about the state of the country under the rule of the BJP.

The number of cases registered and the number of under-trials, convicted and acquitted under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act in the country during 2016-2020 as per the published report of NCRB of the year 2020.

The other glaring issue in India today is the inhumane treatment of political prisoners while in jail, against which Jatin Das had revolted and ultimately attained martyrdom. It is sad that the situation has not changed 75 years after independence. It is well known now that a political prisoner such as Father Stan Swamy died in jail due to sheer medical negligence and inhumane treatment. The octogenarian patient of Parkinson’s disease had to even move court to get a sipper in jail, as he couldn’t drink from glasses due to the shaking of his hand.

Pandu Narote died in jail due to medical negligence.

As of this day, another of the BK-16, Vernon Gonsalves, has been hospitalised in a serious condition after his medical problem was neglected in jail.

Professor G.N. Saibaba, another political prisoner with 95% disabilities due to poliomyelitis, has been facing severely inhumane and cruel treatment since he has been imprisoned in 2017.

It is a reality that in every jail in India political prisoners are treated inhumanely and denied books, clothes, meetings with family members and even basic necessities like spectacles and medicines by a vengeful state. It appears that Jatin Das’s martyrdom has been in vain in the ‘new India.’

Therefore if the government really wants to express its veneration for the freedom fighters who underwent imprisonment under the British in this 75th year of our independence, the first thing it should do is to release the political prisoners of today, who carry on the glorious legacy of the freedom struggle in the multitude of struggles for social, economic and political freedom going on in India today.

This would be the country, “Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high,” which the freedom fighters fought for, went to jail for, and died for.

Partho Sarothi Ray is Associate Professor in Biological Sciences in IISER, Kolkata.