Digital media is increasingly taking over our lives—whether it is social media, digital classrooms or Over the Top (OTT) platforms like Netflix. Even the World Cup is being transmitted not only by TV but also through various apps.

Younger people today have a passionate relationship with their mobiles, giving us time only between the loading of their screens. Along with the rise of digital media, we also have the rise of powerful digital platforms that increasingly determine how we get our news and entertainment while also becoming among the biggest monopolies in the world.

While these digital platforms, such as Google and Facebook/Meta, are often called social media, differentiating them from media, we need to recognise that they are very much a part of the larger media landscape today. Calling them social media differentiates them from older media but only as a new media segment. It can therefore hide in what way the new digital media is similar to older media.

As a Marxist, the key question is how does media earn its revenue? And the answer to both the new social media and the older forms of media is that they have the same revenue model: advertisements! We then need to examine how the new digital platforms have created their monopoly in media and the change it has made to the structure of media.

The Background: The Digital Revolution

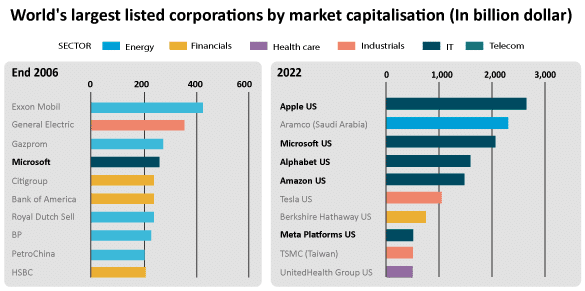

The digital revolution has created new digital monopolies—not just Google and Facebook. In 2006, Microsoft was the only digital company in the top ten global monopolies. Today, more than half of the top ten—or six—are digital monopolies (Figure 1) with Apple having overtaken Saudi Aramco, the biggest oil company in the world!

Among the top five global monopolies, four are digital monopolies with their market capitalisation in trillions of dollars. Apple is the largest producer of the iPhone but does not own a single factory for its production. Only two out of the six are social media companies, counting Google as social media, though the bulk of its profits come from the search engine.

One of the misconceptions about the digital revolution is the belief that data is by itself a product, and this is powering the digital economy, what the World Economic Forum propagated, data as the new oil. The others, influenced by the Italian school of “autonomistas”, talked about how algorithms, through their computations, produced a surplus, the concept of an algorithmic surplus.

What they miss is the purpose for which companies use either the data or the algorithms in the real world. Digital monopolies are not homogenous entities and use data and algorithms differently depending on whether they are Amazon, Microsoft, Google or Facebook.

If we look at the business models of digital monopolies in the top 10 global monopolies, they are quite different. Only two of the digital monopolies among the top ten global monopolies, Google and Facebook, are media monopolies.

They are trying to branch out using their captive users into other domains such as, for example, finance—Google Pay, Facebook Pay and Amazon Pay—but the bulk of their revenue still is from advertising. The core business of Google and Facebook is selling us, their users, to the advertisers, and their business model is the old-fashioned media business of advertising.

The other four in the top ten global monopolies are digital monopolies but with quite different business models. The business of Amazon is buying and selling goods, similar to what the brick-and-mortar monopoly Walmart was and still is, despite its digital forays. And Microsoft’s major revenue is its Windows monopoly, other proprietary software and services built on top of the Microsoft suite just as Apple’s monopoly is as a seller of devices, primarily the premium brand, the iPhone. TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductors), the latest entry into the top 10, is the biggest chip manufacturer in the world.

Clearly, the digital revolution is bringing about a change in the structure of capitalism. So, what is the digital revolution all about?

There are two axes to the digital revolution: one, the communication network and its bandwidth, and the second, the computational capacity of the devices on this communication network. Digital media is the consequence of the revolutionary changes in both the communications network—the internet—through which we send or receive information and the devices themselves connected to the network.

I will use a simple measure of the increased reach of the communications network, the number of nodes (connections) on the internet and the amount of data being transmitted in the network. This shows that the amount of data being transmitted in the network is increasing roughly at the rate of 40% every year and the number of devices by about 18% annually. It is this explosive growth of data communications that drives the need for more computational power in the chips of our devices.

Why is the processing power of chips so important for media? Chips enter in two ways into the media domain. Transmitting moving images for viewing requires not only a fast communications network but also processing power at both ends of the network.

A mobile phone today has hundreds of thousands of times more computing power than the onboard computer that guided the Apollo 11 landing on the moon! This is what we require to see moving pictures in real-time—whether a film, a video on Facebook or YouTube or to watch sports.

There is an understanding that data itself is of commercial value, and the digital revolution is all about data. This view was based on the success of Google and Facebook and the belief that they harvested data from us, the users, and this data provided an inexhaustible resource they are monetising. This view not only limits the digital revolution to only social media companies but also misunderstands the nature of the surplus that digital monopolies generate and from whom.

Media and advertising in the age of the Internet

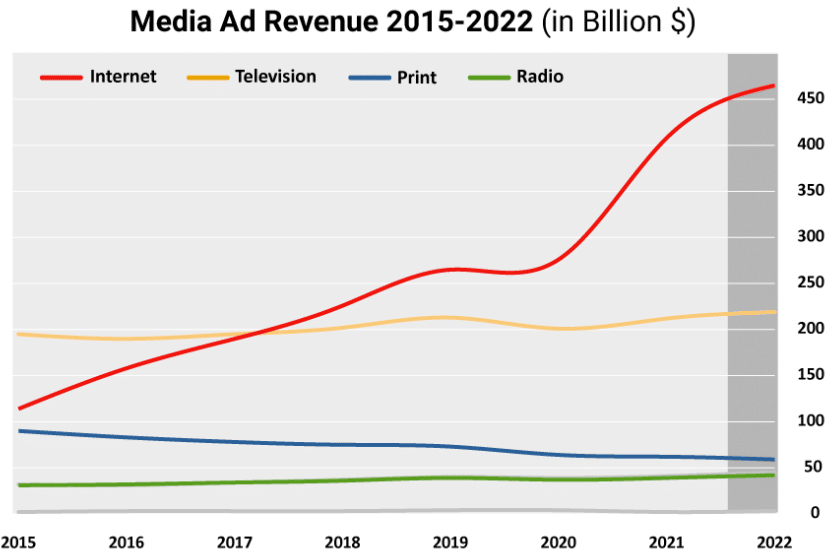

Advertising revenue has shifted in the last decade decisively towards digital monopolies. As can be seen from Figure 2, print and TV, which were roughly a quarter and early half of all ad revenues in 2015, have shrunk to less than one-tenth and about a quarter of the total ad revenues in 2022, a dramatic fall in a scant seven years. The gain has all been for digital platforms, which used to be only a quarter of all the ad revenues but are today more than half of all ad revenues in the world.

How much of the revenue of Google and Facebook is from advertising? In 2021, out of Google’s revenue of $258 billion, 81% was from advertising. For Meta, formerly known as Facebook, a whopping 97.4% of its revenue of $118 billion in 2021 was from advertising. Therefore, we need to place Google and Facebook in the larger context of media and advertising.

For the rest of this article, I will restrict myself to only the digital media platforms, in what way are they similar to earlier media platforms and the ways they are not.

We have already established that the business models of the two digital platforms—Google and Facebook—are based on advertising revenues. In Marxist terms, we also have to understand the source of this surplus and also what it is that a media company, in this age of digital platforms, delivers to advertisers those who advertise their goods on it. I am also going to skip over the role of advertising under monopoly capitalism as this is a much bigger exercise.

I will make only two assumptions from other studies on media and monopolies. One is that advertising competition is preferable to price competition for companies as it retains the total quantum of surplus, the competition being only for its redistribution.

This is the famous competition between Coca-Cola and Pepsi, which avoided price competition in favour of advertising competition. The other is that the revenue for advertising companies only redistributes the surplus which comes out of production. While advertisers also produce ads, commercials, and billboards and have their own production cycle, this production cycle is funded by the surplus of other companies/monopolies.

What happens if an advertising company holds a monopoly on viewers in a particular medium, for example, say it owns all the cinema halls or TV channels in a country? This would then lead to a redistribution of the surplus to the advertiser from those who produce goods as they cannot reach their consumers without the advertiser, and the advertiser could charge a higher rent from the producer of the goods.

Let us start with television, as it makes it easier to understand what a media company sells to those who want to advertise on their channels. Tim Wu, in his book, The Attention Merchants, argues that all of us have a finite amount of attention—he calls it attention capita. The task of media companies is to grab as much of it as they can and sell our attention to the advertisers. Interestingly, talking about the New York newspaper, he does identify the reader as the product, but he focuses more on the attention of the reader as the commodity, not the readers themselves, as the commodity.

Dallas Smythe, in 1977 and well before Wu formulated attention capital, more correctly identified that media companies sell us, the consumers of media, the advertisers. This is what he termed as the audience commodity. He also wrote that communications were the blind spot of Western Marxism for not understanding the political economy of media focussing only on its propaganda role.

While it is important to analyse the content of media, its ideology, and the hegemonic role it plays, it must also be accompanied by an analysis of the economic role of media itself. And if media companies are among the big hitters of global capital, they are playing a major economic role that we need to understand.

What is sold by the media companies to the advertisers are different sets of audiences: diced up into small segments based on their purchasing power, geography, possible needs, and other details. This is how our data is used by digital platforms, not as a commodity by itself, but to create our profiles such that we can be sold more effectively to advertisers. These sets of data are then matched to the product or products of the company and then used to position their ads. We will not go into the complex process of accepting and selling ads on Google and Facebook platforms, but broadly, there are two functions that all media companies play: one is identifying the possible consumers of the products of a company, and second, the actual process of buying and selling of such ads.

The Purpose of Big Media is Advertising Business

Mass media and mass communications have two purposes: a) to attract and hold our attention by giving us news and entertainment and b) to sell us as commodities to advertisers. To be able to sell ads, media companies need our eyeballs, or our attention. None of us—barring a few shopaholics—want to see ads. We consider them a necessary evil for either getting news, analysis or entertainment.

Vineet Jain, the managing director of Bennet & Coleman, the company that owns The Times of India, was quite correct in saying to The New Yorker, “We are not in the newspaper business; we are in the advertising business.” It might have shocked the news readers and even journalists, but the shock was merely one of brutally stating what we have known all along!

There were other alternatives to media being funded mainly by advertisers. If it was funded by subscribers alone, its price would preclude it from becoming mass communication. It could have been state-funded or subsidised. But those were roads not taken and starting with newspapers in the 19th century to television, ads have been the major business model for news organisations.

I am not touching on the other aspect of media, which, for example, Noam Chomsky (co-authored with Herman Edwards) has written in great detail in his book Manufacturing Consent, which remains a classic and relevant even today. If there was any doubt regarding how the legacy print, television media or the new digital media carry news, we have only to see their near homogenous reaction: whether Iraq, Afghanistan or the Ukraine War to the economic war against China. Whether it is The New York Times, the BBC, CNN or the policies of Facebook and Google, they have been very similar. The task of manufacturing consent for the ruling class is common to both the old and the new media.

Leaving out the more protected digital markets, either due to conscious decisions of the countries such as China and Russia to protect their digital space or due to sanctions imposed by the U.S., e.g., Iran, the dominant social media players are Google and Facebook. These two platforms today have more than 90% of the world’s digital ad revenue. So, what is it that they monopolise, and how do they achieve such monopolies?

The internet has led to an enormous increase in connectivity of the communications network as people connect to the internet through their mobile phones and laptops. This increased connectivity has opened up the possibility of alternate ways of tapping into us as an audience and selling us as commodities to advertisers.

There is a structural difference between all earlier forms of data and the new digital media. With older media, the media companies create the content and the delivery network. On the internet, we, its users, create much more content than all other media companies. And the delivery network (at least, initially) was the internet itself, running on existing telecom infrastructure.

Today, the bulk of the content on the internet is created not by the platforms but by those who use them, or what is termed as user-generated content. The number of web pages on the internet is about half that of the total number of people connected to it. If we add billions of Facebook and Chinese social media platform users who have pages on such platforms, practically everybody connected to the internet is a producer as well as a recipient of the content. If we add the video content that users post on a variety of platforms, from YouTube and Instagram Reels to TikTok, no media company can compete with this volume of user-generated content today.

The new digital monopolies do not create content but offer us a platform and tools to create or post our content on their platforms. That is why they are termed “intermediaries”, or those who host other peoples’ content on their platforms. With increasing user-generated content, the distinction between public and private communication spaces of the earlier era has increasingly collapsed. People posting on Facebook or Twitter believe they are having a conversation in a private space while it is occurring very much in a public space.

While one end of the business of Google and Facebook is common—selling us to advertisers—the purpose of why we go to each of these platforms is different. The most likely reason we use Google is to search for information, most of which has been created by other users like us. Its virtual monopoly over the search engine made it the early leader in gathering advertising revenue. This revenue has made it possible for Google to acquire companies such as YouTube, the premiere video hosting site, and Android, the operating system (OS) for most mobiles except iPhones, to expand their reach even further.

Though Android is an open-source project maintained by Google, its control over its distribution has meant that most mobile phone manufacturers accept Google’s conditions, its add-ons and its restrictions. The Competition Commission of India and other regulators have come down heavily against such anti-competitive practices of Google. The U.S. sanctions on Chinese phone maker Huawei meant that it was forced to develop its own OS with its Apps, as Google stopped Huawei from using its Play Store and, therefore, from accessing all the Apps that most users are familiar with.

When we use any of its products—Google search, Gmail or any Android-based mobile phone, Google profiles us by our location, the kind of query we have made, who our friends are, etc., adding all of this to our profile. In addition, they, like other apps or websites, put cookies on our computers/phones when we use their websites or products. All of it helps Google sell us more efficiently to the advertiser, meaning a buck spent on advertising on Google is more effective than any other platform, barring possibly Facebook/Meta.

Facebook, the other major monopoly in the digital platform market, chose a different route. It created a space where you could put up content about yourself and connect to your friends or relatives who knew you. Facebook monitors our data and the data of our network of friends and relations on Facebook, enabling it to monetise us more efficiently.

Facebook’s ability to profile and sell us to consumers is almost as good as Google’s. Before its sharp drop in market capitalisation, its market cap was more than a trillion in august company of Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet and Amazon. This drop is not because of its inability to sell us—its current users—to advertisers. Investors believe that the huge amount of money that Zuckerberg is sinking into his pet project, the Metaverse, will not have suitable returns. Therefore, the drop in Meta/Facebook’s market capitalisation, which is based on the expectation of future profits for capital.

Google’s search engine was not the only one that tried to solve the problem of search; it won the race initially, as its search engine was perhaps better, the search results were not biased, and possibly even dumb luck. Just as Facebook was not the first social media company with the idea of connecting friends and families, it just scaled better initially and emerged as the market leader in this social networking space.

One company had to be the winner in this winner-takes-all games: whoever took the lead initially got the first-mover advantage in their respective areas. Just as Twitter and TikTok have done later, creating a market niche where they are the leaders.

Any media company, be it a newspaper or a TV station, spends a large amount of money to get our attention and hold it. Newspapers require capital investment in printing presses, operational expenses for distribution and news gathering. Similarly, TV requires investment for production and uplinking to either terrestrial networks or satellites for distribution.

Since we create the content, Google’s and Facebook’s investment were initially neither on creating content nor on a delivery infrastructure. We, the users, provided the content, and the telecommunications network provided the infrastructure for delivery. Their main task was to create tools, which we can use to either find the content of interest to us or post our content for our friends and relations.

The mode of advertising on online platforms is also different from that of broadcast media. Since broadcasting, by its very structure, reaches out as a one-to-many communication, it does not know who receives such content. The only information that such broadcast platforms, such as TV, have—via Nielson ratings—is how many people are watching what programme. The only choice that the people watching these programmes have is to flip the channel or not watch TV. This approach to advertising is like a scattergun approach: spray advertisements around hoping they would stick to some people and that you would remember their brand or product when you go out and buy.

Internet platforms chose a different approach. They knew their users very well; the common internet refrain is Google and Facebook know you better than your mother. The internet can deliver what is called targeted ads to get an ad-to-conversion ratio that is much higher than what the broadcast media can deliver. If you are looking for a video camera through a Google search, Google will show you ads for video cameras for weeks afterwards. Or your friend shows the new video camera she has bought, and you, as her friend on Facebook, get ads for video cameras.

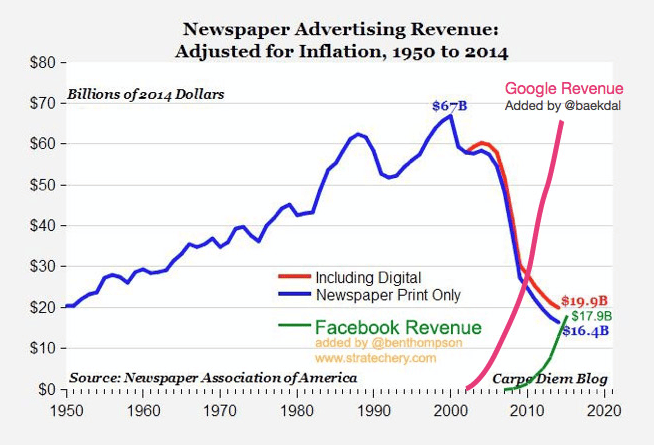

The consequence of this shift in ad revenue is visible today. Print newspapers are losing ads so fast that they are shutting down or converting to online “papers”. TV’s ad revenue is growing but much slower than that of digital ad revenues (Figure 2). In 2017, digital ad revenues overtook the combined TV (broadcast and cable) ad revenues. And out of this, the top two—Google and Facebook—have about 70% of the revenue. The chart (Figure 3) shows not only the sharp rise of the advertising revenue of digital media companies but visually establishes that the fall of newspaper ad revenue is strongly correlated to the rise of Google and now Facebook.

How Did Google and Facebook Become Monopolies?

Both Google and Facebook were led by tech people who understood that in this field, the quality of the technology would be the differentiator between companies. Since they were not selling software, Google and Facebook both used the existing free and open software tools and the community to develop tools for their purpose.

They have also released a number of such tools as open source. Making available some of the tools/platforms provides Google and Facebook with an eco-system for drawing on the resources of the open-source community for further development of the tools.

While Google and Facebook share some of their revenue with content creators, the calculations are not as simple as they claim. One of the monopoly investigations against Google is how it rigs the advertising bids. When YouTube says that it shares 55% of its ad revenue with content creators, it does not tell us how much of the ad revenue is received by YouTube and how much goes to other Google intermediaries. These are the subject of antitrust lawsuits in the U.S. and monopoly/competition commissions in the EU and UK.

Facebook is also facing similar antitrust and ant-competition legal action in both places. This is after the systematic weakening of monopoly laws in Europe, calling them “competition” laws. In the U.S., though the laws themselves were not changed, they were weakened considerably. The interpretation changed, that monopoly itself is not the issue; the regulatory authorities needed to show that consumers or competitors have been hurt due to the monopoly to take anti-monopoly action. This interpretation set a much higher bar for action against monopolies.

When Google became the number one search engine, we had no idea how it could become one of the world’s leading behemoths. It was helping us find content more easily, had no ad business, and its slogan was “Do no Evil”. A nice and cuddly monopoly! The reality has turned out very different.

Larry Page, the co-founder of Google, claimed in 2004 that its purpose was to take you to sites that had content relevant to your search. Today, two-thirds—or two out of three—of your searches end up without a further click, what search engine expert Rand Fishkin calls a zero-click search. The number rises even higher to four out of five mobile searches.

The majority of searches on Google lead to no further clicks on the links in the displayed search pages. Or if links on the search pages are clicked, they mostly lead to other Google sites not to that of the original content creators. This is why Google has a monopoly over internet searches, the only exception being the independent Facebook and Amazon sub-spaces.

Google’s command over all the searches on the internet is only part of the problem. The other is it is a two-sided monopoly. Dina Srinivasan, a leading researcher on monopolies, writes, “In advertising, a single company, Alphabet (Google), simultaneously operates the leading trading venue as well as the leading intermediaries that buyers and sellers go through to trade. At the same time, Google itself is one of the largest sellers of ad space globally.” This means that the marketplace for internet ads is heavily jigged in favour of Google. This is why a number of states in the U.S. are filing cases against Google.

Facebook has no pretence of being an open space. It is a “walled garden” on the internet connecting you to friends, relations and like-minded people on the platform. When you connect to Facebook and interact with others, the platform gets to sell you to its advertisers. Its purpose is to maximise engagement—that is, to keep you on Facebook.

Google had the pretension that the purpose of their search engine is to send you to those who have generated the original content. Facebook, from the beginning, barred any intrusion by others, for example, Google’s search engine from indexing its pages and showing such links on its search results. That is why we call such sites private gardens as they can be accessed only with the owner’s express permission.

So how does Facebook maximise our attention on their site/sites and keep us there? They have worked out that engagement, on Facebook, is driven by our emotions. Fear and hate are stronger emotions than others, and therefore, posts that generate such emotions get more traction and propagate deeper and further within Facebook. This is Facebook’s problem with hate groups. They may make all the noises they want for public relations but are fully aware that the virality of hate posts, and even fake news, is the core of its business model.

The challenge of any new technology is that its speed of spread is faster than the understanding of its social impact. This is not limited to the new digital technologies.

The invention of the printing press was the first instrument of mass communications, creating what we now call the public sphere. It led to the rise of literacy, democratisation of knowledge and transformed society. It also gave rise to newspapers, which were printed, and, therefore, could have a mass readership. Benedict Anderson has identified print capitalism and newspapers as the key to the creation of the nation state.

But the printing press also had other consequences. When the printing press was introduced in Europe by Gutenberg, the first and most popular book was the Bible, known as the Gutenberg Bible. The second most popular book was the Malleus Maleficarum, usually translated as The Hammer of the Witches, the handbook of the Inquisition. How many died as a consequence of the Inquisition? As a result of the nationalist wars in Europe? Due to the looting, genocide, and slavery by colonial powers in Asia, Africa and the Americas?

And yet we look upon the printing press and its expansion of the public sphere as a part of the forward march of history. It increased public participation and literacy, the preserve earlier of the feudal elite, and expanded to even include the working class. It is not an accident that Lenin regarded the Iskra not simply as a mouthpiece of the party but also as an instrument to build the party.

It is not that technology is by itself liberating or enslaving. Any advance in technology has social consequences—both beneficial and harmful. The increase in the productive capacity of technology leads to more being produced and therefore benefits society. It leads—in class-divided societies—to the concentration of wealth and power, the benefits of technological advances are not equal for all sections of society. The battle, therefore, is not for or against technology but on who owns the technology and for whose benefit the increased productive forces are used in society.

The expansion of the printing press and the creation of newspapers led to the creation of the advertising industry. This is what underpins the public sphere in capitalist countries. Advertisements for snake oil, aphrodisiacs, and even cocaine—Coca-Cola had cocaine in its initial secret formula—provided the money for the newspapers and later on, radio and television.

Though certain kinds of advertising have officially been banned or regulated in most countries, the reality of the advertising world is to convince us that we, in our natural state, can be vastly improved by buying, say, a perfume or a fairness cream! It panders to the worst prejudices in society, of which Fair and Lovely ads are only a more sanitised version.

In the U.S., ads for example, routinely portrayed the black community as criminals or naturally violent. But despite the advertising business with all its problems underpinning the media business, it has also created the public sphere. Just as it also helped create Mussolini and Hitler. Mussolini’s radio lectures and Leni Riefenstahl films are again examples that mass media can also be a powerful weapon against the people.

One of the consequences of the struggle against snake oil kind of medicines led to most countries enacting laws on what could be advertised and what could not. These laws also controlled what could be sold as medicines. The problem has been the will to use these laws—whether against Baba Ramdev’s Patanjali empire here or pharma companies selling opioids in the U.S. In addition, it was recognised that media has a major influence on politics, and, therefore, a need to control media monopolies. Unfortunately, the weakening of monopoly commissions and laws and converting them to Competition Commissions has diluted these laws considerably. Monopoly by itself is held to be acceptable unless it can be shown that such a monopoly harms other companies or the people, a much higher bar than when Standard Oil, and AT&T, the telephone monopoly in the U.S., were broken up. Most countries also have laws on what can be published or shown.

The problem in the digital media space is, as we have discussed earlier, the collapse of the distinction between private and public space. When we post on Facebook, put up a clip on YouTube or make a comment on Twitter, we believe that we are speaking privately even if what we are saying is public. The amount of content is also far higher than what can be monitored by public bodies, like a Censor Board for films.

Therefore, in the digital media space, most governments are asking the platforms to police themselves: companies like Facebook and Google should have algorithms for filtering out fake news. This is what the Indian government is also asking the big digital platforms to do.

I am not going to examine here the problems of having algorithms decide on what to censor and what not to censor. Cathy O’Neil, in her book, Weapons of Math Destruction, has dealt with the problems of using algorithms to make human decisions. The issue—what is harmful and what is not—cannot be solved with better maths.

The problem is not who should police the content. It is the task of the creators of content—the users of such platforms— that they conform to the laws. If they don’t, the state and the content platforms have to work together to see that such content is taken out. The problem is that the platforms have the power not only to sell goods but also “sell” candidates in elections and even “sell” legislation and laws to legislators. Asking them to be gatekeepers is like asking the wolves to guard the sheep.

These platforms today also wield far more power than oil, and financial oligarchies did in the earlier centuries. Their net worth, or market capitalisation, is higher than the GDP of most countries.

We need an alternative approach. Tim Wu, in his new book The Curse of Bigness, advocates the break-up of these monopolies to create a number of smaller entities—the same approach taken towards Big Oil and Ma Bell/AT&T. The Just Net Coalition have proposed in The Delhi Declaration for a Just and Equitable Internet that these platforms today are essential infrastructure and should be either regulated as public utilities or be publicly owned.

Technology creates possibilities; it is we who make these possibilities real, including the social and economic structures within which media operates. None of this could happen if the technology of mass communication did not change dramatically, leading to the rise of search engines, social media and the platform economy.

We did not foresee such changes. But once these changes have happened, we need to see how they can be brought in line with the larger goals of humanity and a more humane society. The key issue is who owns this technology and the instruments of mass production of news or views in print, audio, or visual form. Is it capital or is it the working people of this country? This is the challenge of history before us today—the public ownership of the public sphere.

Note: This essay has drawn in part from an earlier essay on ‘Collapsing the Public and Private in the Age of Social Media, in Social Media in a Networked World’, (ed) Pratik Kanjilal and Omita Goyal, IIC Quarterly, Winter-Spring 2019-2020.