In the June 9 European elections, French President Emmanuel Macron’s Renaissance party was overtaken by France’s far-right National Rally (RN) party.

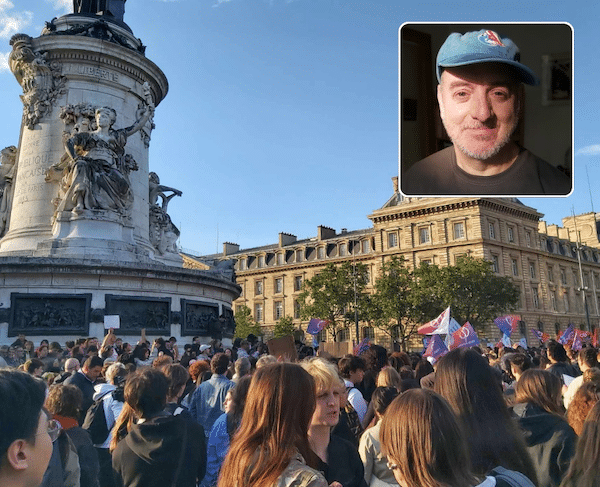

Green Left’s Susan Price spoke with John Mullen, an anticapitalist activist living in Paris and a supporter of the left-wing France Insoumise (France in Revolt, FI) following the far-right’s gains in the recent poll and Macron’s decision to call a snap election.

* * *

In the June 9 European election, Marine Le Pen’s far-right National Rally (RN) party won 30% of the vote, more than double the share of President Emmanuel Macron’s Renaissance party. Can you briefly outline what you see contributed to RN’s success?

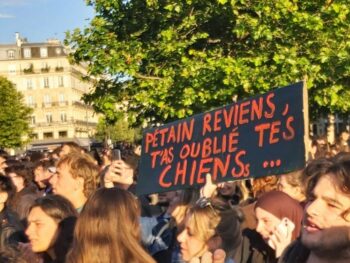

The sign reads: ‘Petain come back, you forgot your dogs’, referring to Philippe Pétain, who led the collaborationist Vichy regime, from 1940-44.( Photo: John Mullen)

There are three elements. Firstly, Marine Le Pen has been extremely successful in persuading most people, over the past 10 years, that the RN is just a party like any other.

An opinion poll last December showed that only 41% of French citizens now consider Le Pen’s party to be “a danger to democracy”. The RN was even able to participate last November in a “march against antisemitism” without opposition from Macron or other participants!

National Rally MPs work hard, turning up at every prize-giving or car boot sale in town, smiling, avoiding controversy, and looking like normal people.

This “detoxification” has been successful despite the fact that the party contains a solid fascist core, and that its election campaign leaflets, under the slogan “France is coming back!” listed as first priority “defending your identity and your borders”.

Leading candidate and president of the RN, Jordan Bardella, spouts endless lies about the economy being ruined by the aid given to lazy asylum seekers, and about the supposed threat of violent anti-French racism.

Secondly, since “divide and rule” has been Macron’s speciality, he has been strengthening the RN by pretending that people with roots outside France — and Muslims in particular — are a threat to the French way of life.

Two years back, [Macron’s] so-called “law against separatism” involved making employment discrimination against Muslims much easier, banning Muslim legal defence organisations, and deporting several Muslim preachers on trumped-up accusations whose main aim was Islamophobic scaremongering. His ministers have claimed French universities are now under the thumb of “Islamoleftists”.

Established news magazines such as Le Point and L’Express, help the RN too, running regular front pages on the “threat of Islam”.

Another of [Macron’s] ministers declared that RN was closer to republican values than was the radical left France Insoumise. In addition, his brutal neoliberal cuts, including attacks on pensions, on health and education services and unemployment benefits, have considerably increased the desperation which can find an outlet in support for the far right.

Finally, the left has not put sufficient attention on opposition to the building of the RN. Most left organisations in France believe that building a left alternative, to hold out hope for improvement in people’s lives, is enough to cut the grass from under the fascists’ feet.

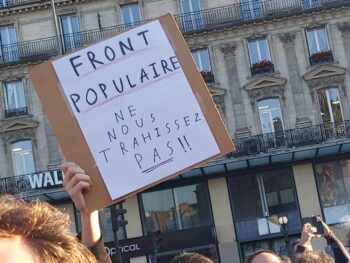

An antifascist demonstration in Paris on June 11. The sign reads: ‘Popular Front: Don’t betray us!’. (Photo: John Mullen)

The specific tasks of stopping the RN from building its organisation — of making sure every time the RN has a local meeting of 20 people there are 50 people demonstrating against, of setting up door-to-door antifascist work in towns where fascists get the most votes, and so on — is generally not being done, with the exception of some local initiatives.

Snap legislative elections will be held in France in early July. Do you think Le Pen will be able to repeat that success? What additional factors will influence the vote?

The legislative elections work very differently, and Le Pen does not have a strong national party network of activists. Nevertheless, the danger is very real. Le Pen right now has 89 members of parliament in the lower house. To have an overall majority, 289 seats are required. At the moment Macron, with his close allies, has 249, and his government has had to negotiate with other parties to get each bill through.

After the collapse of Macron’s vote in the European elections (falling from 22% to 14%), he is expected to lose many seats, and the RN is expected to gain a lot. The RN may also benefit from the deep crisis in the traditional conservative party, the Republicans.

If the RN were to become the biggest single group in the parliament, Macron would appoint their leader, Bardella, as Prime Minister. This would be a catastrophe. As government, the RN would immediately have power over the police and the economy. Its credibility, and its ability to hurt workers, immigrants, LGBT people and so on, would be multiplied many times, while green projects and regulations would be ruthlessly slashed.

Macron is saying he stands against “the extremism of the right and of the left”. By “extremism of the left” he is referring to the FI grouping. The FI has 75 MPs and has done an excellent job of foregrounding the question of the genocide in Gaza, of insisting that taxing the rich is possible, of opposing anti-Muslim racism and of defending in every area the need for improvements in working class lives. This profile allowed the FI to get votes of over 50% last Sunday [June 9] in a number of multiethnic working-class towns like Saint Denis and Bobigny, and to get 9% nationally.

Macron is hoping that, one more time, people will vote for his representatives “in order to stop the far right”. But he has been claiming to be stopping the far right for 8 years, and Le Pen and other fascists now receive millions more votes than they did 8 years ago.

I would not like to predict the results of the elections. No doubt the most likely outcome is a parliament with no overall majority, and a coalition government — but who will be in that coalition is impossible to say.

What are the prospects for the left in the election?

Antifascist protest in Paris on June 11. (Photo: John Mullen)

These elections, for 577 seats, take place in two rounds. A candidate can be elected outright in the first round by getting more than 50% of votes. Otherwise, the second round run-off goes ahead, in each constituency, with the two top scorers, and occasionally a third candidate who got a score over 12.5% and wishes to remain in the race.

If there are several left candidates in a town, the chances of a second round [between] the right and the far right are much increased.

Four organisations — the FI, the Ecologists, the Socialist Party (SP) and the Communist Party — are in negotiations. They have agreed to share out the constituencies so that there is only one left candidate in each constituency. Projections show that this alliance (“the new popular front”) will reduce the number of seats won by Le Pen’s party by several dozen.

The plan is excellent news. The pressure from below, and from trade union leaders and campaigning organisations such as ATTAC for this unity, was unstoppable. On Monday, during the talks, there were hundreds of young people outside the building chanting “young people demand a popular front!” and slogans supporting the alliance are common on the daily antifascist demonstrations we are seeing this week. The New Anticapitalist Party, alongside many other groups, has announced support for the pact.

A minority of left activists are insisting that electoral agreements are not important, and that only antifascist activity in the streets can make a difference, or even that such alliances undermine the antiracist movement. This position is both childish, and, in the present situation, dangerous. If Bardella were to become Prime Minister it would be an extremely serious blow to the workers’ movement and to antiracism.

Anticapitalist activists must get involved in the electoral campaign. The mobilisation will go much further than the political parties involved. Already four of the biggest trade unions have called for antifascist demonstrations across the country this coming weekend. High school students have been protesting in a number of towns. We have two weeks to build a powerful movement to win these elections, and to put pressure on the government which emerges.

How is France Insoumise mobilising on the ground and what platform is it taking to voters to combat the influence of the right?

The left organisations understand that an electoral pact is essential, but also that to attract voters, it must say more than simply “we hate the National Rally”. There are only a few days in which to put together a program, and the program, to be released this weekend, must be accepted by very different political forces.

The FI is having to ally, for example, with some from the SP who recently joined the disgusting smear campaign against its leader [Jean Luc] Mélenchon, (claiming that he was anti-Semitic because of his support for Palestine). The initial declaration announced the need for a “complete break with Macronism”, and it looks like there will be an agreement on a series of urgent measures to be carried out in the first three months if the New Popular Front takes office.

One key measure which will be promised is the immediate cancellation of the raising of the retirement age from 62 to 64, which was brought in last year amid months of mass strikes and protests. Interestingly, Bardella, who had always pretended to oppose Macron’s retirement age reforms, has announced this week that if he becomes Prime Minister, he will not reverse it. This is because the far right is desperately searching for more support from capitalists, who are mostly very hesitant about the RN.

The FI campaign for the European elections was very dynamic, with mass door-to-door canvassing in many towns, and many public meetings overflowing. In the past few days many thousands of new activists have joined the FI groups, mostly young people determined that the fascists shall not pass. Trade unions and campaigning organisations of every description — from Greenpeace to the Human Rights League — are getting involved to stop Bardella.

This electoral campaign is very much an uphill struggle for the left, but there is a lot to fight for. We must remember that 24 million voters stayed home on the day of the European elections, and most of them do not like fascism. We must push for the broadest, most energetic and creative antifascist uprising 21st century France has seen.