The stock market crashed on August 5, in a new “Black Monday”. What caused it? Is the USA on the verge of a new financial crisis?

Ben Norton is joined by economist Michael Hudson to discuss the extreme volatility, AI / Big Tech bubble, Japanese yen carry trade unwind, Chinese economy, and geopolitical dangers.

Transcript

BN: Is the United States on the verge of a potential new financial crisis? This is a question that financial analysts are asking after there was a market crash on August 5. It is being compared to the famous “Black Monday” crash in the stock market in 1987. They also both happened on a Monday. So is this another Black Monday?

This was the biggest market plunge since the beginning of the pandemic in 2020, when many investors were selling off their holdings, fearing that there was going to be a big recession.

In fact, as of the August 5th crisis, the volatility index, the VIX, which is a measurement of how rapidly stock prices move in the S&P 500—which is the stock market index of the 500 biggest companies on U.S. stock exchanges—the volatility index is at the highest level since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic. That’s a very dangerous sign.

Fortune magazine referred to this as a “stock bloodbath”. The world’s 10 richest billionaires lost $45 billion of wealth in one day. And this was especially concentrated among the Big Tech oligarchs, people like Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg, Bill Gates, Larry Ellison.

A lot of the wealth in the U.S. equity market is concentrated in a small handful of Big Tech corporations, which are collectively known as the “Magnificent Seven”, or MAG7.

On the day on Black Monday on August 5, they lost $600 billion in stock value. And these MAG7 companies are Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia, and Tesla. In 2023, these MAG7 companies accounted for half of the S&P 500’s total gains in the entire year. And in one day, they fell around 3%. That, again, is around $600 billion.

In the United States, 93% of stocks are held by just 10% of the American population, the 10% richest part of the population. However, despite that, 58% of households in the U.S. own stocks. This is why it is significant, because many people, especially in the neoliberal era, have been pressured to hold their savings on the stock market. And their pensions are also increasingly private, especially as U.S. government officials talk about cutting and privatizing Social Security. Many retirees have 401(k)s, private pensions, that invest in the S&P 500, that invest in the stock market.

So because so much of the U.S. economy, this big financial house of cards, is built on investment on the S&P 500 and the Nasdaq, this does affect a lot of average people, not just billionaire oligarchs.

The S&P 500 has fallen quite significantly in the first week of August, although it is still up year on year. But this is a pretty significant fall.

The Nasdaq index, which is more heavily weighted toward Big Tech corporations that are publicly listed on U.S. stock exchanges, has fallen even more than the S&P 500.

So what’s going on? Why did we see this Black Monday in the stock market?

Well, there are a few reasons that the financial press is citing to try to explain this.

First of all, it is the unwinding of the yen carry trade. I will explain later on what that means, but essentially it’s because of the difference in interest rates set by the U.S. central bank, the Federal Reserve, and the Japanese central bank.

Investors, speculators, have been profiting from the interest rate differential taking on debt in the Japanese currency, the yen, because of the low interest rate that they have to pay on that debt, and then using that to buy U.S. dollars and investing in U.S. stocks and U.S. bonds, and profiting.

So now the Japanese central bank is raising interest rates, which means that there’s a kind of global margin call. What does that mean? It means that these investors have to provide more collateral in order to pay off their debt, which is now more expensive. So they’re selling their U.S. stocks.

And they were selling Japanese stocks, which is why there is another very significant fall in the Nikkei index of the biggest companies in the Japanese equity market.

So this is the main explanation that we’re hearing: this is the unwinding of the yen carry trade. But there are other potential explanations.

Some economists expect this could be the beginning of the popping of the AI bubble, or the Big Tech bubble. Big Tech corporations have spent hundreds of billions of dollars on artificial intelligence technology. And there are some reports that suggest that actually AI might not be what we’ve been told that we should expect, this great revolutionary technology that changes everything.

Potentially, some financial analysts think this could be the beginning of the popping of the AI bubble.

Others are saying that this is the fault of the U.S. Federal Reserve, that the U.S. Fed has maintained interest rates too high for too long. And they say the Fed must reduce interest rates.

They point to the fact that unemployment in the U.S. is rising more quickly than many people expected. In July it increased to 4.3%.

Then, of course, there are the many geopolitical crises happening around the world: Israel threatening a war on Iran, Israel bombing Gaza, the US launching a coup attempt in Venezuela, the war in Ukraine continuing and NATO potentially expanding that war against Russia, U.S. sanctions against China, the potential of conflict there.

There are so many things happening in the world. And the question that many people are asking is, is this the beginning of a larger financial crisis? Is the U.S. entering recession?

Well, today I have the fortune of being joined by the brilliant economist Michael Hudson, a friend of the show. He is the co-host of Geopolitical Economy Hour, that is hosted by Radhika Desai, a program that we publish here at Geopolitical Economy Report about twice a month.

I wanted to bring on Michael, who has had decades of experience working in financial markets as a world renowned economist, and the author of many books.

Michael, what do you think is happening? What explains this historic crisis in the U.S. stock market? And are we potentially on the verge of a new financial crisis?

MH: It’s not so much that we’re in a recession; the whole economy has been shrinking really, since 2008. The idea of a recession is a fantasy created by the National Bureau of Economic Research. And the whole principle underlying all of its models is that the economy works in a sine curve; it goes up and down, and there are automatic correction factors. Once it goes up, there are internal correction factors that move it down, but it’s always rescued, because when an economy moves down, labor becomes cheaper, there’s unemployment, it is hired again, and employers can make more profits, and there’s a recovery.

This is not how economies have worked for the last 5000 years. What does the National Bureau leave out of account? That every recovery from a recession has started from a higher and higher debt level.

Now the economy has reached the very peak of its debt-carrying capacity, and there is no way that it can recover. Every recovery has been weaker, and weaker, and weaker, because the debt that it has come has been sort of like driving a car and stepping on the brake.

The debt that has been fueling the financial sector is an overhead. It’s paid by the economy at large, by the 90% of the economy that is indebted. Not only wage earners, but corporations, cities and states, and the federal government.

The recipients of all of this gain are the creditor class, basically the 10%, or even the 1%, and especially the 0.1%.

So the question is not if the economy is in a recession which automatically is going to recover; there is no sign that it’s going to recover at all.

The artificial gain in stock market prices and the financial sector since the 2008 crash has been accrued almost entirely to the top 5% or 1% of the population. The economy at large for the 90% has actually been shrinking.

Much of the so-called growth in national income has been financial returns. Interest payments are counted as part of the GDP. Penalty fees are part of GDP. Rising housing prices are counted as part of the GDP. And yet it’s harder and harder for people to buy housing, and they have to pay more and more mortgage debt in order to buy the higher priced housing.

All of this is called the boom, and it’s not a boom at all. It’s impoverishing the real economy of production and consumption. But it has been making money for the financial economy, which is really extractive.

All of these gains really should be looked at as a subtrahend from GDP, not as part of GDP. It’s not really a product. The financial sector doesn’t produce a product. The real estate and rent-extracting sectors, the monopolists, don’t produce a product; they simply charge more. And that’s a transfer payment from the economy to the rent extractors—the recipients of rent, the monopolists, the real estate speculators, but most of all the financial sector.

So if you look at the financial sector as the driving force of the economy, the economy you’re talking about is the economy of the 10% that makes its money by impoverishing the 90%, and therefore impoverishing the economy at large.

So we haven’t been in a recovery since 2008. We’ve been in a steady financial squeeze, a steady decline. That’s called neoliberal growth.

BN: Now, Michael, in terms of the fall in the U.S. markets, we actually saw something similar internationally, especially in the Nikkei index in Japan, there was a massive fall.

It has partially recovered today. We’re recording on August 6.

So some people are pointing the finger at Japan and in particular the Japanese central bank. It does seem a bit goofy, but there’s a lot of discussion of the fact that the Japanese central bank has risen interest rates from -0.1% to 0.25%. So about 25 basis points.

This might seem a little goofy that people are so fixated on a 25 basis-point increase, but this is actually rather significant in that Japan had this ZIRP—zero interest rate policy—going back to 1999, and it does seem that Japan is moving away from that.

So some people are blaming what they call the unwinding of the yen carry trade. What does that mean, for average people watching here?

There was this interest rate differential. The U.S. interest rates were over 5% higher. So you have a lot of investors who would take debt in yen, and then they would use that debt in order to buy U.S. stocks, U.S. bonds, Japanese stocks that have a higher rate of return. And then they would make money off of that global arbitrage, essentially.

Now that the Japanese central bank is raising interest rates, we see that the differential is falling. And then there’s basically a kind of global margin call, where people who are doing all of this leveraged trading, they’re buying up all these stocks and bonds with yen-denominated debt, they’re being forced to sell their stocks in order to pay off their debt, which is now more expensive in yen.

So this is one of the explanations for this kind of new Black Monday event. What do you think of this explanation?

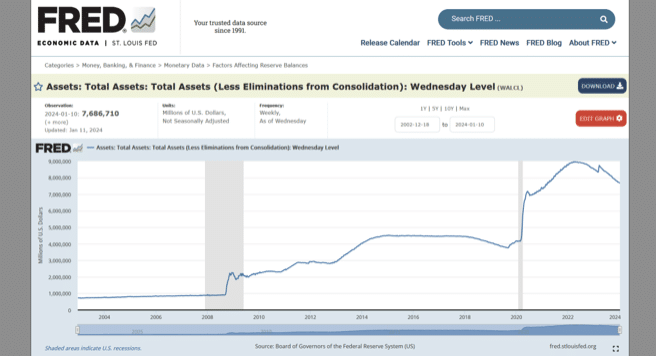

MH: Well, Japan’s carry trade is exactly what has been happening to the U.S. economy since 2008-2009. It’s exactly the same.

So the short answer to why is the stock market crashing is because most stocks have been bought on credit. And the hope is that the price of these stocks, the increase plus their dividends, will be larger than the interest that has to be paid. That’s what arbitrage is. Carry trade is just another word for this arbitrage.

All of this was fueled by America’s zero interest rate policy, after the 2008 crash. You already saw last year, when Silicon Valley Bank went under, when a whole group of banks went under, when the interest rates went up, and that squeezed this whole trade.

So here’s what happened: Speculators borrowed at low interest rates, as you just said. They bought stocks that yielded a higher dividend rate and price gains. And the result is inflow of borrowed money into the stock market, and also into the real estate and bond markets.

So all of this seems to be a guaranteed win, year after year, thanks to the Fed giving the odds in favor of the arbitrageurs.

The zero interest rate policy here, as in Japan, was simply an incitement to borrow. None of this had backing in the real economy of production and consumption.

So I think it’s easier to understand what happened in Japan by looking at what has happened in the United States.

Then I’ll turn to Japan, because Japan had the twist of the balance of payments and the international exchange rates.

When the Federal Reserve made this about-face to increase rates, in order to increase unemployment as part of the Fed’s class war against labor’s wage levels, this became simultaneously a financial war against the stock and the bond market.

So money had been made merely financially. But the U.S. and the European economies themselves were deindustrializing through all of this. And that was because they were being financialized.

So, when you ask why a market is crashing, it all depends on how deeply you want to get in to the cause of this crash.

Crisis is endemic. It has to occur; it always has occurred. In the sense that privatization and financialization tend to polarize the economy, and they impoverish some parts and create a break in the chain of payments, when some part of the indebted economy can’t pay.

Often the break is a mere coincidence, or what economists called exogenous. Well, that’s what happened with the winding down of Japan’s carry trade.

But the crashes always occur. For 100 years, until the early 20th century, most financial crashes occurred in the autumn, because that’s when the crops were harvested, and the agricultural sector borrowed from the banks in New York, and Boston, and Philadelphia, and other centers to move the crops.

That withdrawal of deposits meant some banks didn’t have the money to pay. There was a break in the chain of payments, and that triggered a whole decline.

That’s sort of the model for the kind of crashes that we have had ever since.

In today’s case, the USS zero interest rate policy, like that of Japan, was designed to bail out the banks that were insolvent after 2008 and 2009, because they were so debt-leveraged.

The Fed’s solution was not to recover the industrial economy, but to keep banks solvent, basically, by flooding the economy with credit. And that meant somebody’s debt.

The insolvency of the overall economy was simply postponed by lowering the rate of interest to make the financial sector able to make arbitrage gains.

So now we get back to Japan, and the carry trade, and why that adds a special twist to all of this.

Japan raised its interest rates in a way that was simply a trigger for what happened on Monday (August 5).

Once you have a zero interest rate policy, you can’t simply walk it back. When you end a zero interest rate policy, when you begin to raise rates, you pull down the whole superstructure of debt-financed arbitrage trades, that have made all the borrowing that you’ve been doing at low interest rates to buy stocks, or bonds, or real estate, or foreign currency that yields that higher rate. All that is wound down.

So here’s what happened with Japan’s carry trade. The speculators would borrow from a Japanese bank at a low interest rate, and they would buy United States bonds, or those of other countries, mainly U.S. bonds, that paid a higher interest rate, once the Fed began to raise its interest rates.

Now this involved an exchange of yen for U.S. dollars. You would borrow in yen. You would spend the yen buying U.S. currency, to buy the U.S. bonds yielding a higher interest rate. That threw the yen into the foreign exchange market, and reduced the yen’s exchange rate, and helped push the dollar’s exchange rate up.

That’s why, with the higher interest rates that the Fed has charged, you have seen a rise in the U.S. dollar, despite its trade deficit, despite its military spending. It’s basically a financial raise in the dollar’s rate, not reflecting any of the health of the underlying economy.

Well, when Japan decided to stop fueling this arbitrage, then, all of a sudden, the Japanese or other investors who had been borrowing yen to buy dollars said, “Ok, we can’t make a profit on our trade anymore, because now we have to pay more money to the banks, and that wipes out our opportunity to make a guaranteed free financial ride on the arbitrage”.

So they closed out their position. That meant they sold the U.S. [stocks] to get the money to pay back the Japanese banks for the money that they had borrowed.

That meant that dollars were sold and Japanese yen were bought: a movement out of dollars, into yen, to pay back the Japanese banks. So all of that shifted the interest rates around, in a more than marginal degree.

Well, most of the computer programs and strategies by the financial sector are based on merely making marginal gains. The average trade of stocks is only a few minutes.

If you look at the enormous bulk of the trades—it’s called volatility, which is all computer driven. The computers are designed to say, you see a trend, let’s buy this, and jump on the bandwagon. And a minute later, there will be a price change: Let’s take our gain a minute later.

All of this is short-term squiggles. That’s how the computer programs make money.

That’s called artificial intelligence. And you could say it’s a very tunnel-visioned intelligence. You could call it artificial stupidity. Because it doesn’t take into account how this affects the overall economy.

So the free arbitrage ride has run out, and the result was that this squiggle caught a lot of the arbitrageurs and the automatic straddles of where you borrow in one currency to pay another. All of these interconnected, systemic straddles were interrupted and, as you pointed out, many of the debtors who had been financing all of their bets on credit, all of a sudden had a loss.

What were they going to do? They had to sell other assets that they had that didn’t go down in value, in order to pay the banks, because the banks would have made a margin call. They said, “Well, almost all the money that you have been borrowing for stocks, all of these purchases you have made, you have hardly any of your own capital, maybe 2% of your own equity. And that has just been wiped out by a change of more than 2%. So, we’re going to have to close out your position”.

The result is you have had copper prices going down, and all sorts of other prices throughout the economy went down. It all became systemic. And these computerized automatic sales and transactions were triggered to go on and on.

Well, you had enormous volatility, but yesterday, on Monday (August 5), you had, almost all of the big brokerage house telephone lines and computerized investment lines crashed, because everybody thought, “Well, we know that prices are going up, and you never know when the stock market price is going to go down, until there’s a crash. So let’s just leave our money in, leave it as long as we can”.

What they realized is that the economy doesn’t move in a nice sine curve; it goes up slowly, and then it goes down quickly. It’s a ratchet effect.

Once there was a decline quickly, most people couldn’t—the small investors, pension funds, anyone but the big financial firms—had to just sit quietly and watch the market price of their assets go down.

I don’t want to say they lost wealth, because it’s not really wealth. It’s just all financial counters that went down. They were stuck with all of this.

Ben Norton: You raised so many interesting points there, Michael, and I’ll try to address some of them a bit later. But continuing with this theme of the Japanese economy, what is interesting is that, for the past few years, the Japanese yen has been falling pretty significantly against the U.S. dollar.

In the past few days, at the beginning of August, the yen has actually risen against the U.S. dollar, partially because the Japanese central bank has raised interest rates. And also we were talking about the unwinding of the carry trade and such.

But what’s an interesting part of this is that it’s not just the Japanese yen, but also the Chinese yuan, the renminbi. This is fascinating. The RMB has risen a bit against the U.S. dollar; it has rallied.

This is actually against what many mainstream financial analysts expected. Because there’s been this narrative now that the that the Chinese economy is supposedly so weak. Conservative economists say that the Chinese yuan is only being held up by by capital controls, and that if China lifted capital controls, the currency would collapse.

At a moment like this, like this Black Monday kind of crisis we saw on August 5, usually we have what is called a flight to safety. You know, investors pile into U.S. bonds. And we saw that the 10-year yield on U.S. bonds went down as there was more demand for bonds. So it went under 4%, whereas back in October, it was nearly 5%.

So, at this moment, you did see a flight into safety, but you also saw that the currency in China, the renminbi, rose against the U.S. dollar. Now that’s very interesting.

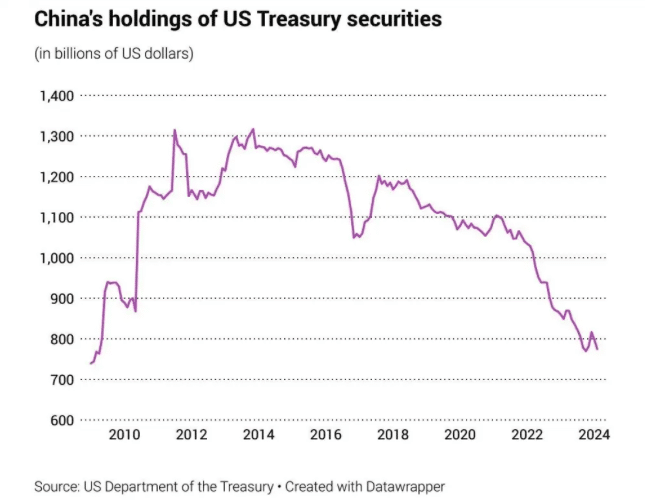

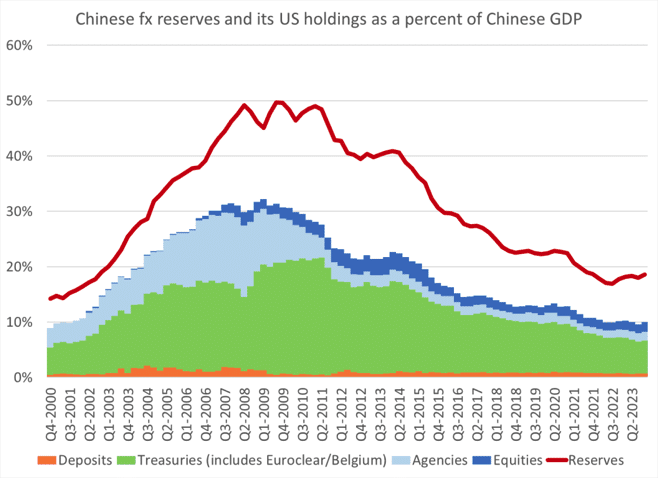

You and I have talked in the past about how China has been de-dollarizing. The People’s Bank of China has been selling its U.S. Treasury securities and instead buying gold.

In fact, the total U.S. government debt held by the People’s Bank of China—not only Treasury securities, but also agency bonds from U.S. government agencies—the total amount of U.S. debt held by China has fallen to the lowest level as a percentage of GDP since China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001.

So do you think that is one of the reasons why the yuan seems to be increasingly moving with other currencies, like maybe the yen, and not with the U.S. dollar?

Why did the yuan rally at this moment of crisis in the U.S. markets?

Michael Hudson: It’s not that it has rallied. If you have the U.S. president, and all of the large American politicians and firms saying, “China is our enemy number one. We’re fighting Russia now, but we’re going to fight China, because it has a different economy; it’s not neoliberal, it’s a socialist economy. And we’re seeing a fight between what kind of economy is better, a neoliberal, financialized, ‘democratic’ economy like us, or an economy that has money and credit socialized, like China. It can’t possibly work; only our economy can work; that way is a disaster. And we’re going to impose sanctions against China, to make sure that the Chinese economy doesn’t work”.

Well, obviously, if you believe that, then you’re going to think, gee, I’d better sell my investments and disinvest from China and Chinese securities.

Well, let’s look at the geopolitical result of all this. China has seen the United States and Europe confiscate Russia’s foreign exchange reserves, claiming that “Russia is the enemy, and it’s the enemy because it’s supporting China, the real enemy”.

Well, if Russia’s reserves have been seized, this makes China’s holding also very hesitant.

Obviously China is thinking, well, when are they going to do to us what they’ve done to Russia?

But there’s also a move by BRICs and other countries to de-dollarize. They see that China’s economy is growing, and America and its European allies and satellites are stagnating.

So they’re preferring to reorient their trade and investment toward the part of the world that is growing and is offering them a win-win situation instead of what Donald Trump says, that only the U.S. has to be the winner in everything.

So you’re having oil exporters denominate their oil sales in Chinese currency instead of the dollar.

Well, obviously, when Saudi Arabia and the Arab countries decide to de-dollarize and do their trade in Chinese currency, and when other BRICs countries decide to reorient their trade away from the shrinking U.S. and European, Western economies, toward China, you’re going to have a movement out of the dollar.

So it’s not so much that there’s a movement into China as such; it’s that the active propeller is the United States, with its sanctions against China, with its threats against China, to de-dollarize, and the fact that the U.S is isolating itself, not only from China, but from the BRICs countries as a whole.

So I think that’s called shooting yourself in the foot.

BN: Well said. Now, Michael, another aspect here that is being discussed is the AI bubble, artificial intelligence. There has been so much investment done in AI technology

The big AI companies had seen their stocks rally very significantly. And many people think that they’re significantly overvalued.

In fact, if you look at the U.S. stock market, most of the growth in the stock market has been in a few companies that they used to be called the FAANG. They had a few different names. Now they’re known as the Magnificent Seven, the MAG7. They’re these seven Big Tech companies, like Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, Meta, which owns Facebook; Alphabet, which is Google; and also Nvidia. Tesla was in the MAG7, but it was kind of taken out because its stock has been falling.

So some people suspect that this could be the beginning of the popping of the AI bubble.

What is interesting is, if you look at the Nasdaq index, which is more heavily weighted toward the Big Tech companies in the U.S. stock exchanges, Nasdaq fell much farther than the S&P 500. The S&P 500 is the 500 biggest publicly traded companies in the U.S. stock exchanges.

So it does seem to suggest that the Big Tech companies were hit harder by this.

This also came after Intel, which is a major chip-maker, announced that they were laying off 15,000 employees, which is about 15% of its workforce.

Immediately before this, right before the the Black Monday event, billionaire Warren Buffett’s investment company Berkshire Hathaway sold roughly half of its stake in Apple, which actually is huge because because Berkshire Hathaway had about $174 billion invested in Apple as of the end of 2023. That meant that it had roughly a 6% ownership stake in Apple. And they sold about half of that, around $80 billion.

Of course, Apple has been investing very heavily in AI.

So what do you think, Michael? Could this be potentially the beginning of the bursting of the AI bubble, or in general, the Big Tech bubble?

MH: Well, AI has one great advantage. Nobody really knows what it is. And so this is very much like what happened in 1998, when there was a similar move into, high-tech, information technology stocks.

BN: You mean the Dot-com Bubble.

MH: Yeah, the Dot-com Bubble crashed.

Now, Apple decided that it really wasn’t going to be very much of an AI company anymore. It gave up on AI. Almost all of Apple’s earnings have been spent either on raising the dividends or on stock buybacks. It said, “As a company, our aim is not to make new research and development”. It’s no longer part of the AI revolution.

Apple said, “So we’re just going to use the inertia of the income that we have had just to buy our own stocks and to push up the stock prices, and not do research and development, because if we do research and development, then that’s going to reduce our earnings, because we’re spending our money on new capital formation, and that’s the opposite of making money financially”

If you spend money on new research and development and capital formation, then you fall behind. The result is that, Apple, like other American companies, are falling behind China and socialist countries that are not using their firms to increase stock prices and make financial fortunes, but to actually create new technology and new production. So you could call it services that I think by now China will be including that in its GDP and their national income.

You mentioned Intel. Well, Intel has been in agony for the last half year, because the Biden administration has said, “China is our number one enemy; you must disinvest from China. Don’t sell it computer chips, because some of these computer chips may be used for a military purpose, and they can help Russia. And we want to defeat Russia, so that we can then go and attack China”.

Well, Intel said, “Wait a minute, one-third to 40% of our market is in China. If you prevent us from selling our chips to China, we lose the big market there”.

The Biden administration says, “We don’t care if you lose. This is a fight for the death. Either the Western neoliberal civilization will vanquish all the rest of the economy, and make the whole world unipolar, or the rest of the world is going to pass us by. This is a fight to the death. You have to disinvest and not sell your products to China”.

Well, Intel just lost its biggest market. And the United States tried to block it from selling maybe to nearby Asian countries, like Singapore, that would buy chips and then sell them to China.

So of course Intel has gone down. If you’re going to take away the Asian market from U.S. information technology, or computer chip companies, or high-tech companies, then they’re not going to have the money to invest in new technology.

If these companies decide to let their financial managers run them to make financial returns and high stock prices by paying out their earnings as dividends and stock buybacks, instead of research and development, then of course China and Asian countries, South Korea, and other countries, are going to pull way ahead.

So the U.S and neoliberal economies have an idea that, fortunes, which they call wealth, are to be made financially, not by tangible, industrial investments. Fortunes are to be made by de-industrializing the economy, and living in the short term, not by industrializing the economy with long-term economic growth.

Essentially that is the problem that is facing economies. And I think that is why, Warren Buffett realized, well, the apple run-up is over now. It has announced to the world that it is not going to participate in the expensive research and development that is needed to become a world competitor, and to out-produce the main U.S rival in information technology in China.

So that is really what happened on Monday (August 5).

You had stock market investment advisors say, we really don’t know why these AI companies are going way up. It’s sort of like Amazon used to be. Their stock prices are going way up, far in excess of the discounted rate of their dividend payouts.

So if you’re buying Nvidia or other companies that have led to this gain, you’re not really making money off their dividends; you’re hoping to make money off the capital gains that the herd instinct is leading to buy them.

Everybody thought, “Well, we’re going to just leave our money there, and, the trend is our friend, and we’re going to ride that trend, and then, we’ll sell out, once it looks like the peak is over. We’ll sell and we’ll just take all the gains that we’ve made in the last few years for this run-up”.

Well, as I mentioned before, once you try to sell, you’re going to have everybody at the same time seeing that it’s time to sell. They can’t reach the brokers by the telephone. They can’t go online and press the button that says sell, because they’re overloaded. And the decline is so great that it has wiped out much of their gain, especially if they have gone into debt and bought these stocks on credit to maximize their debt leverage gains.

When the debts have to be repaid, all of a sudden, there has been a rush to sell off. And the rush to sell off, to liquidate their loans, is a crash. So, that’s what happened.

But the crash isn’t simply a technical financial crash. It’s a crash in the whole neoliberal idea of getting rich in the AI sector, in the same way that you get rich in the other sectors, not by research and development in developing a product, but by riding a Ponzi scheme, basically.

You borrow the money, you hope to buy and you hope that you can pull out your money before the other people who have jumped on to the scheme sell, and you leave the new investors holding the bag.

I think Warren Buffett said he’d rather be the first to pull out of this Ponzi scheme, than later. And so other people see him pulling out, and then they’re pulling out, and say, “Well, wait a minute, these companies aren’t really paying a dividend; they’re not really producing a profit that makes money, in the sense that you can pay out a dividend. Their output is being blocked from being sold to the largest market, China and the rest of Asia”.

So America has really sanctioned its own economy. The neocons have sanctioned the AI industry from trade with the largest market.

So what what has that done? It has forced China and other countries to say, “Well, if the United States is going to impose sanctions and prevent us from buying computer chips and other inputs that we need for our information technology, we’d better produce these goods ourselves, so that we won’t be left in the position for the United States to just block and interrupt our production by stopping some essential input along the whole chain of inputs, especially computer chips”.

So you have had China and other countries say, “We no longer have an open, free market international economy. The United States is trying to disrupt our economy. We’re going to protect ourselves from U.S. disruption by being self-sufficient in computer chips and other technologies. And we’re going to develop our own AI”.

TikTok is an example. When they develop a system that works like TikTok, America, the Biden administration, says, “Any information technology can be military. You could be spying on us with your videos”. That’s the pretense.

The U.S. says, “We’re going we’re going to force you to sell. If you, you Chinese and Asians, have an economy that is making money, you have to sell this company to the Americans, so the Americans get the money. You can make all the profits you want, but these profits have to be paid to American investors, not to your own investors”.

This is crazy, geopolitically. This is an announcement to the rest of the world, “You’d better go your own way and stay as far away from the U.S. as you can, because we want to hurt you and disrupt your economy, to take it over, so we get all of your games. And we treat Asia like we have treated South American raw materials exporters, African exporters. You’re existing to make us profits, and if we can’t profit from you, we’re going to wreck you”.

Well, of course, this is forcing them to go their own way. And this was where the largest market for AI was. The neocons have destroyed that market. And by doing that, they have destroyed America’s own potential leadership in the AI industry. So why buy AI stocks?

BN: That’s actually a perfect segue, Michael, because I also wanted to ask you about the potential geopolitical implications of this U.S. market crash.

Of course, we’re we’re seeing right now that the war in Ukraine is continuing, and there is more and more escalation by NATO, potentially threatening to expand the war on Russia.

We are also seeing that the U.S. is backing this brutal Israeli war on Gaza, and Israel is also attacking Lebanon and Iran. They already killed a Palestinian militant inside Tehran. And now Israeli officials are talking about opening up a full on war with Iran.

So what do you think will be the impact of that?

Of course, you mentioned the U.S. sanctions against China and export restrictions targeting China.

What what are the geopolitical implications of what’s going on in U.S. markets right now?

MH: Well, everything is geopolitical, because the whole world economy is an overall system, just like the human body, or the weather, as part of an overall system.

We have been talking about how, when the Japanese bubble was winding down, the arbitrage bubble, that caused losses for some investors, margin calls; it spread throughout the whole international financial sector.

So it’s obvious that there is going to be a big war in the Near East. Iran says that they plan a retaliation over the assassinations that have occurred there, going all the way back to the general, Qasem Soleimani, that, President Trump assassinated.

Nobody can tell just how far the United States is going to escalate. Its battleships and its carriers in the Mediterranean have been moving there, essentially to send information for where the Israelis should bomb. More battleships have been moved into the Straits of Hormuz, to oppose Iran.

All of this looks like it’s developing on a final push, not only by Iran, but now with Russia, with its chief military officer, Sergei Shoigu, going to Iran yesterday (August 5).

This is an attempt to drive the United States out of the Middle East—out of Iraq, where the U.S. is emptying out its oil wells as fast as it can; out of Syria; even out of Libya. You have Turkey agreeing. You have a whole series of diplomats visiting each other to coordinate what is going to happen.

The U.S. military has said that, in every military game that they have planned out, the U.S. loses there. So no matter what, they’re going to lose. And Biden essentially says, “If we’re going to lose, we might as well blow up the whole world. What the hell, I have Alzheimer’s anyway, it doesn’t matter to me”.

U.S. diplomats have been going to Iran and saying, “Can you just make a proportionate response to the fact that they attacked you?” And the Iranians have said, I assume, something like, “What do you mean, ‘proportional’, white man? You have killed, 200,000, probably 500,000 Palestinians in Gaza. What is proportional? Do we kill 500,000 Israelis in Haifa? That’s proportional. Do we wipe out Tel Aviv, like they have wiped out, not only Gaza, but the West Bank? That’s proportional”.

The Iranians probably say, “You’ve killed our leaders. What do we do? We’re not going to kill you, Mr. Biden. You’re such an idiot. We want you to stay there. No, we want to protect you, and your Vice President Harris. Absolutely, just keep on doing what you’re doing. But we’re going to end your presence and your military bases here in the Near East”.

“The game that you’ve been playing for 100 years, to try to use Near Eastern oil, to control the world economy, by threatening to turn off other countries’ access to oil, to interrupt their supply chains, and stop their factories from running, or their electric utilities from providing heat and electricity—the game is over. It’s not reversible. It’s not that, we’re going to stop your game and then, ok, we’ll go back and reverse things. This change that is happening, it’s irreversible. We’re going to do it. And we’re going to do it in one week”.

There is some talk that it may be on August 12 or 13, which is Israel’s holiday for some great big victory, or religious event.

So, Iran says, “This is non-negotiable. What for us is proportional to your take over the Near East? We’re reversing that. That’s proportional. You’re out of the Near East now. And we have Russian support. We have the support of Lebanon. We have support of our neighbors. And you will no longer be able to use Israel as your landed aircraft carrier to try to break us up”.

“And then we’re going to go after your military bases all throughout the rest of Eurasia. The game is over”.

That’s really what is shaking things up.

Well, you would think that some people investing in the stock market would think, “This is a pretty serious threat. Maybe we just better sell out and put our money into Treasury bonds, and get interest”.

I’m obviously anthropomorphizing all of this. But I think this is what President Putin and Foreign Minister Lavrov have been talking about. And there were wonderful speeches by Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, who has been talking about where this is leaving Europe, sort of left out.

So, yes, globalization is quite important, because globalization means, is there going to be war?

Globalization is about the split of the global majority away from the U.S.-NATO countries, their Golden Billion population, from the rest of the countries. And where is that going to lead to leave the stock market?

And beyond the stock market, where will that leave the economies that have now moved their industrial production abroad. They have de-industrialized their economies. Where is this going to leave Germany, and Europe, where, now that they have lost their ability to import gas at a price that will enable their industrial companies to make a profit, you’re already having European companies trying to relocate either to the United States, where they can buy less costly oil and gas, or to Asia, and possibly even to China.

You’re having the whole world reorient. And this is such a structural shift that, of course, that’s just sweeping the stock market and financial markets aside.

Finally, it’s all put in the geopolitical context. But I can guarantee you that there’s no artificial technology or stock trading program that takes the geopolitical dimension into account.

BN: So, Michael, you have shown in your work how the U.S government has essentially inflated a big asset price bubble for 16 years now, since the 2008 financial crisis, and how the Fed had interest rates that were very low and even zero, and also used quantitative easing, buying up assets like mortgage-backed securities, that were these toxic assets that no one wanted to buy.

This had the effect of inflating asset prices and pumping up a big bubble in the stock market.

The rich benefited from that. They got richer and richer and richer. Inequality got significantly worse.

I talked at the beginning of our discussion today about how 93% of stocks in the U.S. are held by 10% of investors. These are the rich elites.

However, at the same time, because in the neoliberal era, there has been this push for everyone to use private pensions, there are more and more discussions of cutting Social Security and privatizing Social Security, so many people have 401(k)s and private pension funds, so that means that 58% of people in the U.S. are invested in some way in the stock market.

So my question would be, do you think, especially with the election coming up in November, and so many pensioners and retirees holding much of their savings in the S&P 500, in the stock market, and of course, the billionaires, the oligarchs who fund political campaigns, do you think that the government will try to act, to try to re-inflate the bubble in the stock market, and try to basically bring back that wealth that was lost in this stock market crisis?

MH: There’s nothing that the U.S. can do to stop the stock market from falling. There’s nothing that they can do directly to push up the stock market.

All the Fed has been able to do since 2008 is to offer low interest, free money. You have free money; use it to buy stocks and bonds, and make an arbitrage gain. So at least you stock owners and bondholders, you 1% of the population, can save your skins, and do whatever you’re doing with your wealth.

So, the whole policy since 2008 has been to essentially cut interest rates. But you can’t stop the stock market from falling by going back to say, “Ok, we’re going to roll back interest rates, we’re going to go back to zero interest rates. Now start borrowing again and building up the stocks”.

This is an irreversible process. Because, what was happened since 2008? In order to roll back the clock, you would have to roll back the enormous increase in financial debt that has occurred. Most debt is within the financial sector itself, even more than between the financial sector and the rest of the economy. This can’t be rolled back.

So what can the economy do? Well, the U.S. is not about to say, “Ok, we’re going to revive the economy by making the United States look like China. We’re going to become a socialized American economy. And, we’re going to stop financialization. We’re going to merge the Fed back into the U.S. Treasury, and only create credit and banking to increase the means of production”.

They’re not about to do that, because then they wouldn’t be the United States, and they wouldn’t be a neoliberal country.

If you look at just who is involved in the stock market, much of the money that is being lent is by U.S pension funds. The pension funds have tried to make money desperately, because corporations don’t like to set aside enough money in their pension funds to really afford to pay pensions. They’re way underfunded.

So what we’re discovering is how crazy it has been to organize pensions and Social Security on a financial basis, saving in advance in the financial markets, instead of a pay-as-you-go system, like you have in Germany, for instance.

So the pension funds are so desperate to make money that they’ve turned the money over to private capital (private equity) companies.

This is essentially an extractive way of making money. Suppose that a corporation lends its pension fund money to a private capital (private equity) firm, and the firm makes a killing by borrowing money to take over a company. And it may take over the very company that has put its money into a private capital fund.

Well, one of the first things that the private capital (private equity) company would do would be, “Let’s sell the company’s buildings and real estate to a subsidiary of our firm and you’ll sign a lease, and instead of owning the real estate and the buildings, they will pay rent for the real estate. And they will then use the sales price of all of this real estate, they’ll pay it out as dividends, a special dividend, and that’ll make money for the PC (PE) firm, as part of the deal.

And then the PC (PE) firm is going to use this sales price, in addition to paying itself a dividend, it’s going to do what companies like Thames Water in England does; that’s sort of the model for how a PC (PE) company works.

It will borrow money to pay out its dividends, or to buy stock buybacks, to raise the price of the stock, and make money for the existing stockholders, as long as they can keep doing it.

Well, all of this sale of property and taking on debt leaves the company more highly indebted, and with more highly operating rental costs to pay rent for the buildings and the real estate that it used to have for itself, without having to pay.

So the PC (PE) firm has made a killing, and the investors and the company stock has gained. But at some point, most of this debt service and the real estate cost has left no more profits for the firm. In fact, the firm won’t have enough money to pay its bills. It begins to pay its suppliers less. Finally it does what Toys R Us and Sears have done: it goes bankrupt.

That’s the PC (PE) plan, to make money by driving companies bankrupt. That’s why, on an economy-wide basis, the United States is de-industrializing. It’s de-industrializing because that’s how to make money financially the most rapidly. That’s the neoliberal strategy.

So creating a financial asset price boom in this way is sort of a euphemism for deindustrialization.

Wall Street calls it “creating wealth” and “increasing the productivity” of its partners and employees by how highly they’re paid to empty out, the victims, the companies that it manages to take over.

This is what’s happening throughout the whole Western economy.

So we’re getting back to your question about, what can the U.S. government or the Fed do to restore the S&P index? It only has one option: it can bail out the largest Wall Street companies that are deemed systemically important: City Bank, Chase Manhattan, Bank of America.

Really, that means the politically best connected companies, with the largest campaign contributors, the largest lobbyists.

The people who are the parties that are bailed out that do not include the pension funds, or the small investors. You’re going to have a scale model of the Obama 2008 bailout.

So there really can’t be a restoration of a financial bubble that didn’t have any grounding in the real economy to begin with.

BN: So, Michael, I do agree with you, but just to play devil’s advocate, what would you say to people who argue that, yes, debt is unsustainable, debt continues to grow. But, if you look at a country like Japan, they have shown that you can have debt, in the case of public debt, at over 200% of GDP, and adding in all the private corporate debt as well, and household debt, you can continue pumping up this bubble of debt going on, and on, and on, simply by maintaining low interest rates.

You were talking about private equity funds. These private equity funds, their entire business model was based on the fact that interest rates were zero, which meant that, basically, they were borrowing money for free.

In fact, they were being paid to borrow money, because over time, the real interest rate is below zero, because inflation is higher than the interest rate set by the Fed.

So what would you say to people who say that they can just continue pumping up this bubble if they drop interest rates, and make the cost of borrowing money free, and allow all of these companies to continue to leverage up. They will take on more and more debt; they will buy more stocks and pump up prices.

Private equity will take on more and more debt, and buy up companies, and sell them for parts.

I guess you could say the only thing that’s stopping them from doing that is inflation.

So what do you say to that argument?

MH: This is a totally false, way of framing the issue. The idea of “real interest rates” is so unreal, that, you needn’t pay any attention to anyone who uses that.

The idea of a negative real interest rate is saying, “Look, the price inflation of consumer goods and services is actually going up more than the interest rates”. Well, the financial sector doesn’t care a bit about that.

The billionaire doesn’t care if prices of goods and services, the consumer price index, goes up, because they don’t use their money to go to the grocery store; they use their money entirely to buy more stocks and bonds financially.

All that the financial sector and the wealthy, financialized 1% care about is making money financially.

There is no linkage to the real economy of production and consumption, except to loot it, to empty it out, to make money by breaking up companies, indebting them, and leaving an empty corporate bankrupt shell in the process.

This whole idea that somehow you have to make the investors whole, that you have to keep interest for them, making enough money so they can afford to go to the grocery store—this is an utterly false way of looking at the world, because it assumes that the financial sector is part of the real economy.

Think of it as a layer, or even a parasite wrapped around the economy, sucking out the economy’s surplus.

That’s what my book, “Killing the Host”, is all about, exactly this process.

The financial sector has put a lot of money into propagandizing the population, to misrepresent the financial sector, as if it’s part of the real economy, helping it grow, instead of emptying it all out.

BN: This is such an important point that I’ve only seen you, and Radhika Desai, and a few other economists and political economists talk about, which is that, when we talk about consumer price inflation, using the CPI, consumer price index, that ignores the major asset price inflation that we have seen for decades now.

So what you’re essentially saying, Michael, is that the inflation data that most economists use, whether it’s the PCE or the CPI, that’s not the real inflation data. And what we need to actually look at is the asset price inflation as well.

The government’s policy, not only in the U.S. but in other countries with neoliberal economies, has been essentially to inflate away the wealth of most average working people in order to inflate the assets of the rich.

MH: Yes, and asset price inflation is what they call capital gains. But they’re not industrial capital gains; they’re finance capital gains.

I’ve published charts showing that the increase in capital gains each year, for many years, in the U.S. economy, is as large as the entire GDP.

So what you look at is not simply the rate of asset price inflation—in other words, the stock and bond market index, or the real estate price index—it’s the magnitude of the capital gains, the increase in the stock market valuation, the bond market valuation, and the real estate valuation.

Each year, the change is as large as an entire year of GDP. That’s like a 100% return, you could say, every year, on the economy.

That’s why making wealth financially is so much quicker, and more certain, and more predatory, than making wealth by earning money, earning profits, earning wages, and reinvesting them in savings.

The fortunes in America and other countries are not made by saving up your wages or companies saving up their profits. They’re all made by financial inflation of the stock markets, debt-leveraged inflation, that loads the economy down with debt, so that you can create a rip off, basically, a financial transaction that empties out the real economy, and leaves the economy with a debt, while the 1% of financial managers have already taken all the income, and cashed out their capital gains, and are now looking for where they can move all their fortunes into some other economy.

They would hope to move it into China, but they can’t do that anymore. So where are all these financial gains going to end up?

It’s like you you have short circuited the financial system. That means the end of the whole post-war era—the whole take off from 1945, when the economy of America and other countries had very little private sector debt, to the huge, huge debt we have now—has reached, its limit.

The amount of debt can no longer be paid without cutting back living standards. Wages may go up, but the cost of living is going to go up even more than wages, with cutting back social spending, Social Security, Medicaid, Medicare, other programs. That’s the crisis that we’re having.

And that, of course, is not even an issue in the political campaign that we’re seeing this year.

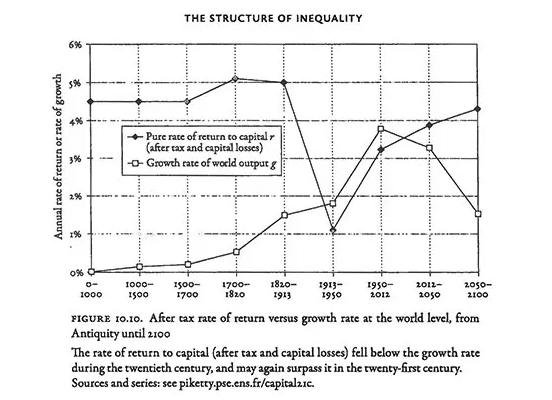

BN: What you were saying, Michael, about debt growing faster than the economy, and also capital gains, this was the famous conclusion of the book “Capital in the 21st Century”, by the mainstream French economist Thomas Piketty.

He famously showed—I mean, it’s a pretty simple observation—that r>g, meaning return on capital is greater than economic growth.

But I think what’s very interesting about your argument here is that you’re pointing out that the return on capital is the flip-side of the growth in debt, that those are directly related, the growth in debt and the capital gains. They’re the same thing, because one person’s debt is another person’s asset.

So what you’re essentially saying is that, the reason that the return on capital is larger than economic growth, is because of the ballooning debt that can never be paid off, precisely because the capital gains grow faster than the economy.

MH: Yes, I have had a number of discussions, with the author of the book “Capital in the 21st Century” (Thomas Piketty).

I’ve said, “Why don’t you talk about this debt issue?” His solution is simply, what the French economist Saint-Simon had in the early 19th century: “Well, let’s just tax inherited wealth. All of this wealth that you’re talking about is inherited. If you can just tax inheritance, you’ll get rid of it”.

Well, it didn’t make much progress in the 19th century. And here it’s 200 years later, and it still hasn’t made progress. He hasn’t focused on the debt issue.

We’ve had a lot of productive discussions, many of which are on the internet. That is basically where we we differ. I focus on the debt issue.

BN: Well, Michael, this has been a very interesting conversation. Let’s start wrapping up.

I want to ask you, as a final question, if you think there’s something that is missing here from this conversation.

I’ve gone through some kind of the main talking points in the financial press. We’ve also analyzed the geopolitical element.

What are the other factors that are missing from this analysis?

MH: Well, what’s missing from the general discussion? Not your questions, and not our geopolitical discussion, or what you’ve talked about on your site, but from the general discussion in the mainstream media, is the long view, and its geopolitical context.

The artificial intelligence program we’ve talked about, running on computers to buy and sell stocks, and bonds, and foreign currencies, has the same tunnel vision that characterizes today’s economics curriculum, if you’re taking an economics course in order to understand the economy.

As I said, you could call it artificial stupidity. It’s sort of like when you call a health insurance company or a public utility to complain about some something wrong in billing; you get a computerized conversation, and they ask you questions saying, you know, press a button on your phone to answer.

That’s artificial intelligence, when you’re stuck on one of these runarounds. And the result has no room for any complicated problem that you may be having.

Well, the computerized programs that dominate the financial trading on Wall Street is like that tunnel vision.

The big context is what you’ve just said: that today’s overhead can’t be paid, or that it can’t be paid without transferring income and property from debtors to creditors.

That’s why the economy is polarizing. 90% of the economy owes debt to the 10%, that are creditors.

Pensions, as I’ve said, are one kind of debt that can’t be paid. The government has a pension insurance fund, but it doesn’t have enough money to pay for the shortfalls in all of the pension companies. It’s too small, to bail them out. It’s under-capitalized. Just as the corporate pension funds themselves are under-capitalized.

So this is why the United States government is going to do what Macron has done in Paris and say, “Well, we’re going to have to raise the pension retirement age, before you get your pensions, because we can’t, afford it anymore”.

The Biden administration has a brilliant solution to the pension problem that I hadn’t thought of: let everybody get Covid, tell them not to wear masks, just wash your hands. That’s certainly going to decrease life expectancy quite rapidly.

Making money financially is mostly done by predatory policies that are de-industrializing the economy. And that’s why the U.S and the European economies have become so de-industrialized.

What people don’t realize is that there’s so much anti-government, libertarian discussion, that governments have relinquished economic planning, thinking that now we’re going to have a free market. But when you relinquish economic planning—really, every economy is planned—so you relinquish it to Wall Street, and the City of London, and the Paris Bourse, and the Nikkei of Japan, and other financial centers.

As we’ve said, their aim is to make money financially, not to help the non-financial economy grow. And these financial gains that are made are transfer payments.

You would need to restructure the whole national income and product accounts to treat, financial services and as a subtrahend. Many services are productive, not financial services, not the FIRE sector services, not monopoly services, not the service of banks in charging late fees to its borrowers. That’s not really a service; that’s an extractive transfer payment that doesn’t belong at the national product accounts at all, but should be a financial subtrahend.

The result is something geopolitical. We’re no longer in a world where states the active factor in deciding how their economies and populations are going to develop.

It doesn’t matter who people vote for—especially in the United States, in this election, which is why the turnout has been dropping so much.

I think you can look at today’s Western states, from the United States to Europe, as agents of a supranational power, a financial power, but also a power that enforces its control by military means, as you’ve seen, culminating in the war in the Middle East today.

It’s an attempt to make the entire world try to follow this financialized neoliberal system, euphemizing it as “democracy”, when actually the voters, and the governments, don’t have much of a political role at all. The governments have had to attract financing by imposing creditor-oriented rules that enable the government to borrow from the financial sector, instead of simply creating their own money.

When China wants to invest and provide money to its industrialization, it doesn’t say, “Let’s borrow from the Chinese, so that we’ll have enough money to fund it”. They simply print the money through the People’s Bank of China. And they don’t have this whole creditor class, this financial class, that has existed in the West.

We’re really dealing with a different economic system that is so basic that you could call it civilizational. That’s what’s left out of the discussion, the fact that there is an alternative to the way in which the Western countries are going this way.

That’s why China, and Russia, and the BRICs are withdrawing from the U.S., and NATO, and World Bank, and IMF system. And they’re trying to go their own way by sort of restoring what textbooks said is how industrial capitalism is supposed to be doing, evolving into socialism, involving into the government providing basic needs, at a subsidized rate, to make the economy more competitive, so that corporations and industrial employers, don’t have to pay enormous wages, enabling labor to pay $50,000 a year for its own education, enabling labor to pay huge medical insurance costs that take up 18% of the GDP, as is in the United States.

We’re talking about a whole different phylum, or classification, of economies that is occurring.

That’s what’s left out in the discussion, and it can’t be discussed, because that would call into question all of the most basic assumptions of what economies are all about.

Iff you believe that the only kind of economy is a Western, U.S. style, liberalized, neo-liberalized economy, then you don’t believe that China really could have taken off. And you don’t believe, you could say, that civilization could have taken off.

If Milton Friedman would have got in a time machine and gone back to Sumer and Babylonia and said, “Here’s how to organize the economy: privatize it all and make all the debts be paid”, you would have ended up like the fall of the Roman Empire already in 2000 B.C.

If you take an even longer view, you could say that the ultimate cause, Aristotle would call it the ultimate cause, really goes back 2500 years, to the whole way that Western economies are structured.

A Western civilization became a distinct civilization from the Near East and Asian and Eurasian civilizations. It took a different path.

Because all of these other civilizations, to take the long view, had canceled the debts when they became too large to pay. That’s what my books are about, like, “… and Forgive Them Their Debts”.

They had rulers who canceled the debts when the crops would fail. Because if they didn’t cancel the debts, then the cultivators who had to use money when the crops were harvested to pay the debts, couldn’t pay, and they would have fallen into bondage to the creditors, and the result would have been to create a creditor oligarchy that would have overthrown the kings, to become a Western-style government.

Well, when Greece and Rome were sort of attached, or were traded with around the 800 BC, Greece and Rome, with the Western economies, didn’t have any divine kingship or any king that was empowered to cancel the debts. Their local chieftains or warlords became the creditor class. And they didn’t have any tradition of debt cancellation.

They impoverished the whole economy. And you ended up with Greece and Rome being part of the collapse of the Roman Empire, when the debts got so large that they impoverished the whole economy by enriching this 1%, or 0.1%, that ended up with all the land, and had turned the indebted population into serfs, under feudalism.

So, you could say that this the tendency of debt to grow faster than the economy was able to pay has been occurring for the last 2500 years.

This is sort of the same structure this has led to today. We have an oligarchy, not a government that puts the economic growth of the economy first.

So the financial sector had sort of established these symbiotic linkages, with real estate, and insurance, and monopolies, and mining companies, producing natural resource rent, and, as I said, all of this is a subtrahend from the real economy. And that’s why the real economy’s been shrinking.

So all of this focus on the stock market, as if, when President Biden, and Paul Krugman, says, “How can they complain that the economy is looking bad? Look at how well the stock market’s been doing”. Well, all of this is saying, “Look at how well the 1% has been doing; forget about your 99% of the population”.

Maybe you’ll win the lottery, and maybe you can join the 1%. But you’re not going to make it by being part of the industrial economy, making wages.

Well, that’s the great blind spot in Western society. And the blind spot is to imagine that the failure that we’ve had in productivity and living standards to rise can be solved by a purely financial solution.

As I said, all that the government can do is bail out the losers, and it’s only going to bail out its own campaign contributors, the donor class, and the politically connected financial sector.

It’s not going to bail out the population as a whole; it’s not going to bail out the pension funds; it’s not going to bail out the indebted economy of homeowners and consumers, who are trying to break even.

They’re looked at as the collateral damage of the financialized economy.

BN: I think that’s a perfect note to end on. I want to thank Michael.

We were speaking with Michael Hudson, the great economist and author of many books. For anyone who wants to read more of Michael’s articles and books, you can find links to all of that at Michael-Hudson.com.

Michael, I want to thank you for joining me.

For people who don’t know, Michael is the co-host of the program Geopolitical Economy Hour, that is hosted by Radhika Desai, that we publish every two weeks roughly here at Geopolitical Economy Report.

So, Michael will be back very soon for for more analysis. Thanks a lot, Michael. It was a great discussion.

MH: Well, I’m glad I was able to get all the big picture. And thank you.