Every winter, I enjoy attending the Studio Ghibli film festival at the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry. There’s a great nostalgia among certain Americans these days, a desire to relive pieces of their turn-of-the-millennium childhood and I won’t pretend to be an exception. Seeing classic films like Porco Rosso and Princess Mononoke on the IMAX screen can recreate what that time meant for many of us, for just a little while, and catching The Boy and the Heron this year was almost as magical. There’s one such film the museum shows that I’ll probably only see once, though: Isao Takahata’s 1988 masterpiece The Grave of the Fireflies.

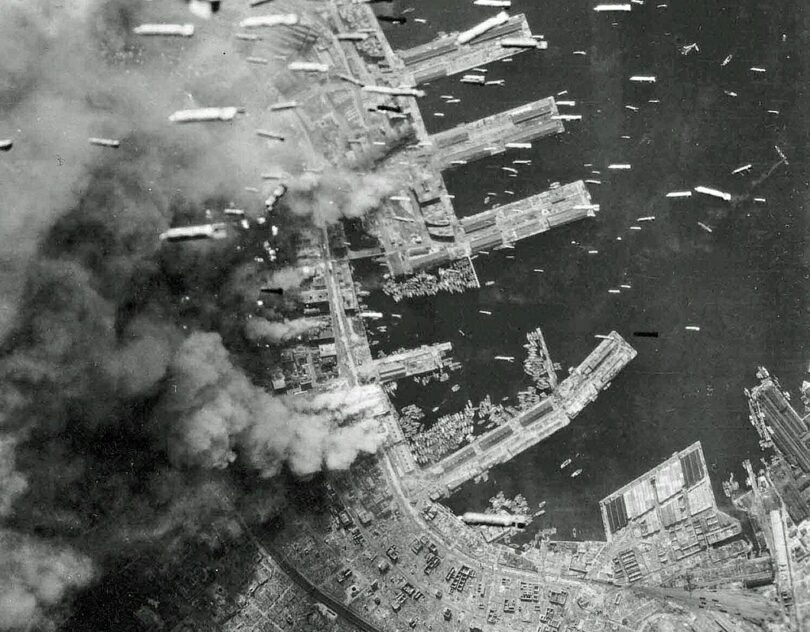

Those who have seen it understand why. But if audiences everywhere find it difficult to sit through its characters’ gut-wrenching fate, it’s no less difficult here to confront the how Takahata portrays Americans in his film. That is, not at all—only as the faceless, indifferent operators of distant terror machines that rain down fire on women and children from the sky. It’s not very comforting to realize that this is how much of the world still sees us.

Japan today is an occupied country. U.S. military planes and helicopters enjoy exclusive access to much of its airspace and have passed overhead for decades after the events depicted in the film. The Japanese government, perpetually controlled by the U.S.-backed Liberal Democratic Party, is compelled to defray the cost of a U.S. garrison of fifty thousand troops within its borders, most of which abide menacingly in the southwestern Ryukyu Islands (also known as Okinawa), where they are notorious for their abuses.1 Only this summer, news broke that the government had covered up five sex crimes committed by U.S. soldiers in Okinawa Prefecture just since last year, one of which involved the kidnapping and sexual assault of a minor, most of which had gone unprosecuted.2 Similar incidents have occurred throughout at least the past few decades in Japan, as well as in South Korea, which also hosts tens of thousands of U.S. soldiers and the largest overseas U.S. military base at Camp Humphreys.3

We know why the Ryukyuans and Koreans suffer—so we could fight Russia. And then China. Then North Korea, then China, then Vietnam, then China, and then Russia again, but always and now especially China. Japan’s ideal strategic location commands the coast of East Asia, and the United States has waged open warfare or economic siege all along that coast for half a century. With the same bland indifference as the warplanes of 1945, the U.S. high command has acknowledged that it ended the lives of one million Korean civilians in the early 1950s.4 Hundreds of thousands of Cambodians and Laotians were killed by the U.S. Air Force in the same manner in the 1960s and ’70s, and millions of acres of the Vietnamese jungle were defoliated with chemical weapons that continue to kill today. Google “Agent Orange hydrocephalus.” You won’t thank me.

Of course, there is no end of propaganda in the United States, then and now, to justify all this mass murder, explicitly or otherwise. Korea and Vietnam had invaded themselves—surely, we couldn’t stand by and let such a thing happen? Even prominent members of Congress still publicly defend the atomic bombing of Japanese civilian populations as necessary to end the war in the Pacific, ignoring a growing consensus among historians, based partly on the now-available Soviet archives, that the Soviet Union’s offensive against Japanese-controlled Manchuria was far more concerning to Japan’s wartime leaders than atomic weapons.5 It is, unfortunately, quintessentially American to believe that foreign countries will only respond to force and can only be truly intimidated by a really big bomb.

As you read these words, the drums of war are beating again. China and North Korea, we are told, are escalating tensions, issuing new threats and provocations, performing more military exercises, and conducting more missile tests. Seldom is it mentioned why such escalations are happening. They don’t seem to have a cause at all; they could not possibly be countermoves in response to escalations by the United States, because nothing the United States does can be in any way escalatory.

It could certainly not be an escalation for the U.S. Navy to send its warships through the South China Sea, as it has done regularly since 2015 in what the United States has called “freedom of navigation” voyages, or through the Taiwan Strait, as it has a hundred times since 2007 and continues to do with greater and greater frequency.6 After all, were China or any other maritime power to send their warships to the Gulf of Mexico, the U.S. government or press would surely have no objection. Surely it couldn’t be an escalation for the U.S. military to operate a secret disinformation campaign in the Philippines to undermine public perception of Chinese-made vaccines for COVID-19 at a time when tens of thousands of Filipinos died from the virus, or to expand its presence in the Philippines and Papua New Guinea in 2023, or to land a B-52 bomber in South Korean airbase for the first time last October, or to send a nuclear-armed submarine to a South Korean port for the first time last July.7 If the government of China was at all alarmed by the revelation of the presence of U.S. troops on the islands of Kinmen in March of this year, a mere three miles from the Chinese mainland, this was surely an overreaction, just as it would be highly irrational for China to take any particular notice of the United States staging its largest-ever war games in the Philippines in May.8 When president Joe Biden publicly takes credit for convincing Japan to increase its military budget, it should apparently be of no consequence to Japan’s neighbors, yet when President Xi Jinping remarks that despite his suspicions that the United States might be trying to goad China into attacking Taiwan, they would not take the bait, it can only be a sign of China’s hostility and unpredictability.9

It is clearly an absurd idea to place no blame on the United States for our collective ascent on the staircase of military and political tensions. Press any American on this point and they will surely agree, if for no other reason than their partisan allegiance. President Donald Trump’s tariffs and trade war with China, for example, were decried by the Democrats no less fiercely in 2018 than Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan was by Republicans in 2022.10 (Many Americans, of course, will condemn both, but you will not easily find one who thinks both parties have done a fine job.)

Now, with all this in mind, suppose the U.S. government chose instead to de-escalate and withdraw from its role as “protector” of South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, and the Philippines? What would happen?

Even posing such a hypothetical will preclude this article from being published in any mainstream paper of record. Such an idea is so heretical, so unthinkable, that no politician or major public figure can give voice to it. The U.S. right to occupy these countries is so unchallengeable in public discourse that many Americans may be unaware that U.S. forces are there at all. But since it has nevertheless just been posed, let’s continue the thought experiment, if for no other reason than its novelty. It could be that, if given a chance, the nations and governments of East Asia might prove a little more reasonable than our press seems to give them credit for. They might recognize in such a development an opportunity for mutual benefit, rather than bloodshed.

There are currently many problems facing both sides of the Korean peninsula. The North has suffered for decades under U.S. and international sanctions, unable to trade for fuel in any legitimate channels, struggling to maintain its agriculture, and compelled to focus instead on its nuclear program, as its best shield for escaping the far worse fates of Libya or Iraq. The immense wealth accumulated by the South—the world’s fourteenth-largest economy—could do a lot of good, if it were invested in the Northern countryside. Meanwhile in the South, households have one of the highest levels of debt in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, nearly 40 percent of all elderly people (those over 65 years old) live in poverty, and with the world’s lowest birth rate, the country faces a serious demographic challenge.11 Social and political integration with the North has the potential to solve every one of these problems. Northern natural resources could boost the stagnating South Korean high-tech economy and reduce its dependence on foreign supply chains. Combined, the Korean population could far more easily become sustainable. Northern policies of public housing and gender equality, if applied broadly, might ease the harsh disparities in the South and, freed from the enormous burden of military spending, the entire peninsula would have much more resources to distribute to its people.12 A fantasy, perhaps; but to think that such a positive future is even remotely likely to come to pass at the point of a U.S. gun would be the height of arrogance.

The Chinese government has repeatedly made clear it regards the question of Taiwan’s independence to be its “red line,” yet polls have consistently shown that the majority in Taiwan currently favor neither independence nor integration with the mainland, but the persistence of the status quo.13 There is good reason to believe that if the United States deescalates, they will have their way. Taiwan is a small island with few resources; its importance, to both great powers, lies in its strategic location and in its semiconductor industry, which is by far the most advanced and productive in the world. Yet now that the mainland is rapidly developing its own semiconductor industry despite U.S. sanctions, this importance is diminishing.14 If a U.S. withdrawal also diminishes the island’s strategic value, then the plain fact will be that in the very near future, the mainland will not need Taiwan at all, though Taiwan may need the mainland. The initiative will then belong to the Taiwanese, just as they desire.

The bitter rivalry between China and the Philippines over the waters of the South China Sea may catch the most headlines of any conflict in the region these days, and surely the blame for it can be spread across all parties. Yet the same logic applies. There is not much within the South China Sea that China would want, if the sea’s strategic value were to disappear. There are no habitable islands. Fishing rights currently form the basis of many such disputes, and as China shifts to aquaculture to meet its demand for seafood and brings stronger environmental regulation and reduced fuel subsidies to its fishing industry, these waters will be sought after less by China than by its neighbors.15 The fossil fuels, too, that lie beneath the sea will be needed less and less as China continues its massive, rapid, and historic shift to renewable energy. Gasoline consumption in China peaked in 2023 and is expected to continue to decline as the production and adoption of electric vehicles skyrockets.16 China makes an expansive claim to the South China Sea primarily because it is surrounded. While the United States controls nearly the entire first island chain, China’s only avenue for maritime trade with the rest of the world lies through those waters. As the blood-thirstiest U.S. media war hawks continually and publicly fantasize about “chok[ing] off [China’s] oceangoing trade,” China increasingly sees its survival tied to maintaining access to this critical gateway.17 The Philippines, however, has no such limitations. It can trade with whomever it likes anywhere in the world, being a sprawling archipelago with many unobstructed Pacific coasts, which would be quite difficult for any navy to blockade. If China were no longer encircled, negotiations over who gets which part of the sea would likely bear more fruit (or fish).

Finally, Japan could gain an opportunity, for the first time in generations, to determine its own destiny. Presently, the islands face many of the same problems that beset South Korea, in addition to an even more stagnant economy that has not grown significantly since the 1990s. There is little doubt that Japan wants change; the approval rating of the Liberal Democratic Party, which has loyally served the United States for generations, recently sank to 25 percent, the lowest since the party’s brief interregnum in 2009.18 According to a poll by public broadcaster NHK, 80 percent of the Japanese population do not approve of the distribution of U.S. troops in Japan.19 The people do not wish the further militarization that is being thrust upon them and the aging population will certainly not sustain any serious conflict.

These are of course all very optimistic scenarios, and will no doubt be more complicated and unpredictable in practice. There is always the danger that old resentments in the region will resurface, particularly between Japan and the victims of its own colonial empire in the early twentieth century. But it is also currently the role of the United States to stoke such resentments, in order to keep the different nations of East Asia divided by hatred. The people themselves are not so easily swayed. This June, when a Chinese man attacked a Japanese woman and her child with a knife in Suzhou, a Chinese woman named Hu Youping intervened, sacrificing her life to save them. Her actions were praised by both the Chinese community and the Japanese embassy, and the Chinese government swiftly cracked down on “nationalist sentiment” online that was considered to influence the attack.20 The wish for peaceful resolution and reconciliation remains far stronger than its opposite.

I have no doubt that whoever oversees the U.S. government next year will not follow my advice. Instead, we are likely to see more escalations, more provocations, and an even stronger and more militarized U.S. presence in the Pacific. But I also don’t doubt that the peak of U.S. power is in the past, and that’s where it should stay. The 1990s that many of us are so nostalgic for were not so magical for the rest of the world, which suffered horror, starvation, and destitution, from the cruel shock therapy in Eastern Europe to the wars engulfing Africa to the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997. The world is stronger now, not so defenseless. The longer the United States waits to face reality, the more painful that reality will be.

Notes

1. Tim Weiner, “C.I.A. Spent Millions to Support Japanese Right in 50’s and 60’s,” New York Times, October 9, 1994; Hiroshi Asahina, “Japan Greenlights $8.6bn to Host U.S. Troops,” Nikkei, March 26, 2022.

2. Shohei Sasagawa, “Hayashi Reveals 3 More Sex Crime Cases in Okinawa Kept from Public,” Asahi Shimbun, July 3, 2024.

3. John M. Glionna, “Alleged Rapes by U.S. Soldiers Ratchet up Anger in South Korea,” Los Angeles Times, October 20, 2011.

4. Blaine Harden, “The U.S. War Crime North Korea Won’t Forget,” Washington Post, March 24, 2015.

5. Alexandra Marquez, “Sen. Lindsey Graham Says Israel Should Do ‘Whatever’ It Has to While Comparing the War in Gaza to Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” NBC News, May 12, 2024; Associated Press and Vladimir Isachenkov, “Historians: Soviet Offensive, Key to Japan’s WWII Surrender, Was Eclipsed by A-Bombs,” Fox News, August 14, 2010.

6. Jane Perlez, “U.S. Sails Warship Near Island in South China Sea, Challenging Chinese Claims,” New York Times, May 10, 2016; John Power, “US Warships Made 92 Trips through the Taiwan Strait since 2007,” South China Morning Post, May 3, 2019; Christopher Bodeen, “China Criticizes US for Ship’s Passage through Taiwan Strait Weeks before New Leader Takes Office,” AP News, May 9, 2024.

7. Chris Bing and Joel Schectman, “Pentagon Ran Secret Anti-Vax Campaign to Undermine China During Pandemic,” Reuters, June 14, 2024; US Department of Defense, “Philippines, U.S. Announce Locations of Four New EDCA Sites,” press release (US Department of Defense, April 3, 2023); Ryo Nakamura and Rurika Imahashi, “U.S. Military to Use Papua New Guinea Naval Base for 15 Years,” Nikkei, July 19, 2023; Chae Yun-hwan, “U.S. Strategic Bomber B-52 Lands at S. Korean Air Base for 1st Time,” Yonhap News Agency, October 17, 2023; Martha Raddatz and Luis Martinez, “ABC News Exclusive: Inside the US Nuclear Ballistic Missile Submarine in South Korea,” ABC News, July 20, 2023.

8. Austin Ramzy and Joyu Wang, “Taiwan Acknowledges Presence of U.S. Troops on Outlying Islands,” Wall Street Journal, March 19, 2024; Nick Aspinwall, “Philippines, US Simulate Mock Invasions in Largest Ever War Games,” Al Jazeera, May 9, 2024.

9. Joseph R. Biden, “Remarks by President Biden at a Campaign Reception” (The White House, June 20, 2023); Demetri Sevastopulo and Joe Leahy, “Xi Jinping Claimed US Wants China to Attack Taiwan,” Financial Times, June 15, 2024.

10. Haris Alic, “House Republicans Blast Nancy Pelosi’s Taiwan Trip: ‘Photo Op Foreign Policy,’” Fox News, August 9, 2022.

11. Yoo Choon-sik, “Managing Household Debt,” Korea Herald, April 22, 2024; Yoon Min-sik, “S. Korea’s Sky-High Elderly Poverty Edges Even Higher to 38.1%,” Korea Herald, March 11, 2024.

12. Se Eun Gong, “Elections Reveal a Growing Gender Divide across South Korea,” National Public Radio, April 10, 2024.

13. “China’s Xi Tells Biden: Taiwan Issue Is ‘First Red Line’ That Must Not Be Crossed,” Reuters, November 14, 2022; Chao Yen-hsiang, “Over 80% of Taiwanese Favor Maintaining Status Quo with China: Survey,” Focus Taiwan, February 23, 2024.

14. Vlad Savov and Debby Wu, “Huawei Teardown Shows Chip Breakthrough in Blow to US Sanctions,” Bloomberg, September 3, 2023.

15. Hongzhou Zhang and Genevieve Donnellon-May, “China’s Fisheries Policy Makes a Belated Shift to Sustainability,” East Asia Forum, April 7, 2023.

16. “China’s Gasoline Demand to Peak Early on Fast Adoption of EVs,” Bloomberg, August 4, 2023; Daisuke Wakabayashi and Claire Fu, “For China’s Auto Market, Electric Isn’t the Future. It’s the Present,” New York Times, September 26, 2022. For a transitional and backup power source, China instead still relies mainly on coal—though carbon emissions likely peaked last year as well—and there is surely no coal that can be extracted from the South China Sea.

17. Michael Beckley and Hal Brands, “How Primed for War Is China?” Foreign Policy, February 4, 2024.

18. Miki Nose and Taishu Yuasa, “Japan’s Ruling LDP Registers Weakest Support since Return to Power,” Nikkei, February 26, 2024.

19. CBS News, “U.S. Soldier in Japan Charged with Sexually Assaulting Teenage Girl in Okinawa,” CBS News, June 27, 2024.

20. Kelly Ng, “China Honours Woman Who Died Saving Japanese Family,” BBC, June 27, 2024.