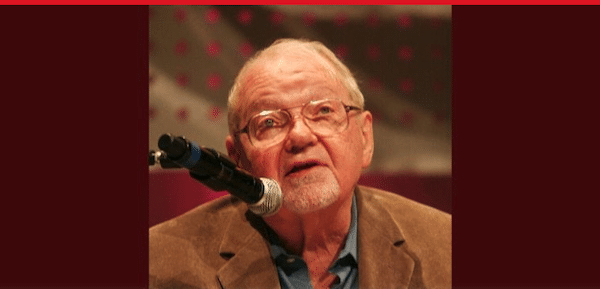

In Fredric Jameson, who died on Sunday at the age of 90, we have lost probably the most creative Marxist thinker of our time. This is a strong claim to make about a specialist in French literature who spent his life teaching at elite universities in the United States. But it’s true all the same.

Jameson’s importance became clear early on, with the appearance of his second book, Marxism and Form (1971). Here he introduced a generation radicalised by the movements of the 1960s to the tradition of what he called “dialectical criticism”.

This embraced brilliant Marxist theorists of culture such as Georg Lukacs, Ernst Bloch, Walter Benjamin, Theodor Adorno, Herbert Marcuse, and Jean-Paul Sartre.

At the end of the book Jameson writes,

The works of culture come to us as signs in all-but-forgotten-code, as symptoms of diseases no longer even recognised, as fragments of a totality we have long since lost the organs to see.

It was the task of dialectical criticism to restore these fragments to their place in this invisible totality—capitalism.

Jameson understood “culture” very broadly. He wrote about William Shakespeare, JW Goethe and George Eliot, but also about detective stories and science fiction. He avidly consumed and commented on film and TV as well—The Wire figures in Inventions of a Present, published earlier this year.

In his most important theoretical work, The Political Unconscious (1981), Jameson boldly claims that “the political perspective”—he means Marxism—is “the absolute horizon of all readings and interpretations”.

This is because it allows us to understand history as the “absent cause” of all our strivings. In it the “ground bass of material production continues, … yet conveniently muffled and intermittent, easy to ignore”.

But “history is what hurts, it is what refuses desire and sets limits to individual as well as collective praxis.”

Jameson argues that Marxism does not simply reject what appear to be rival theories. Instead, it recognises that they offer partial, limited perspectives on reality. It takes over their insights and integrates them into its understanding of the social whole.

Notably in Valences of the Dialectic (2009), he brilliantly addresses the work of thinkers typically counterposed to Marx, for example, Michel Foucault, and incorporates the truths they have to offer.

The same method is at work in probably Jameson’s most famous essay, Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (1984). Here he surveys a range of cultural phenomena, from Andy Warhol’s painting to the new corporate architecture, that were examples of a new “cultural dominant”, postmodernism.

These expressed the changes undergone by capitalism as it became genuinely global with the victory of neoliberalism.

It is precisely this whole extraordinarily depressing and demoralising original new global space which is the ‘moment of truth’ of postmodernism.”

Jameson argued it is more important to understand this cultural transformation than to criticise or condemn it—as other Marxists, for example, Terry Eagleton and myself, did. This didn’t lessen Jameson’s commitment to the Marxist critique of capitalism.

In 1991 he responded defiantly to the apparent triumph of Western imperialism at the end of the Cold War. “Capital and labour (and their opposition) will not go away under the new dispensation,” he said.

Whether the word Marxism disappears or not, therefore, in the erasure of the tapes in some new Dark Ages, the thing itself will inevitably reappear.

Jameson’s writing was often difficult. He was famous for the length and complexity of his sentences. You would puzzle away at them, sometimes totally in the dark—and then, suddenly, the lights would flash on, and you would have learned something new. For someone so formidably erudite and accomplished, the author of over two dozen books, Jameson was personally modest and unassuming. Numerous tributes bear witness to how much his students loved him.

Jameson wasn’t an activist. But a 1981 photograph of him with Yasser Arafat and other Palestinian activists and their supporters—widely circulated on social media—shows he knew which side he was on. Whenever I wrote to him asking for his signature to support a campaign, he would quickly email back his agreement. He will be much missed.