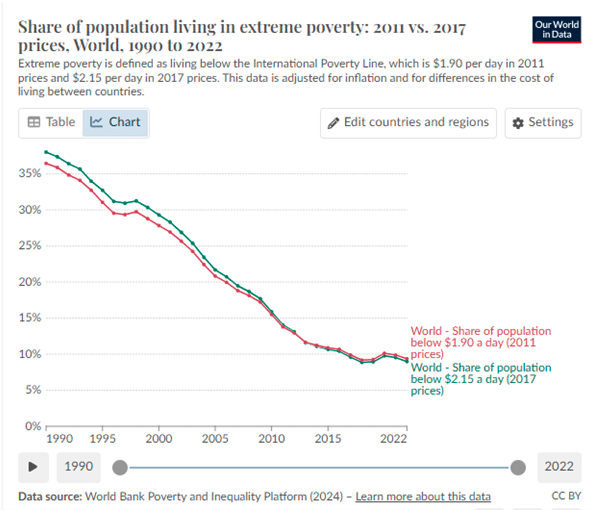

To track progress towards its goal of eradicating extreme poverty by 2030, the UN relies on World Bank estimates of the share of the world population that fall below the so-called International Poverty Line (IPL).

In 1990, a group of independent researchers and the World Bank examined national poverty lines from some of the poorest countries in the world and converted those lines into a common currency by using purchasing power parity (PPP) exchange rates. The PPP exchange rates are constructed to ensure that the same quantity of goods and services are priced equivalently across countries. In all these statistics, the researchers not only took people’s monetary income into account, but also their non-monetary income and home production.

An IPL of $1.90 a day was derived as the mean of the national poverty lines of 15 poor countries in the 1990s, expressed in 2011 PPPs. The selection of these 15 poor countries was based on limited data at the time. With the gathering and analysis of new data from other low-income countries, the reference group was expanded. The IPL is now derived as the median of the national poverty lines of 28 of the world’s poorest countries, expressed in 2017 PPPs.

In September 2022, the figure at which this poverty line was set shifted from $1.90 to $2.15 a day. This reflected a change in the units in which the World Bank expressed its poverty and inequality data—from international dollars given in 2011 prices to international dollars given in 2017 prices. This means that anyone living on less than $2.15 a day is considered to be living in ‘extreme poverty’. Just under 700 million people globally are in this situation.

World Bank estimates of the share of people living in extreme poverty globally for 2019—the latest available year—is 8.4%, or about 700m.

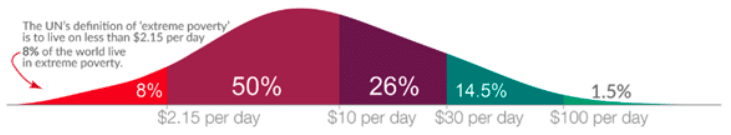

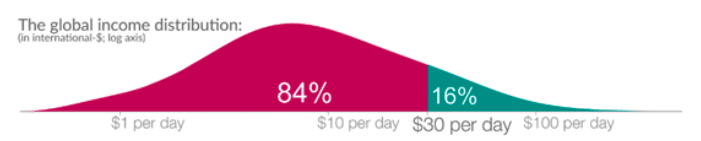

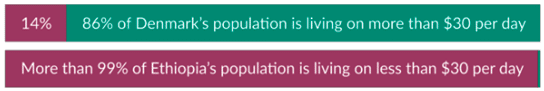

But this global figure does not give an accurate measure of poverty. There are poor people in every country, people who live in poor housing and who struggle to afford basic goods and services like heating, transport, and healthy food for themselves and their families. So the definition of poverty differs from country to country, but in high-income countries, the poverty line is around $30 per day. Even in the world’s richest countries, a substantial share of people—between every 10th and every 5th person—lives below this poverty line. If we apply this $30-a-day-poverty-line to the global income distribution, it shows that 85% of the world population—live on less than $30 per day. That means 6.7 billion people.

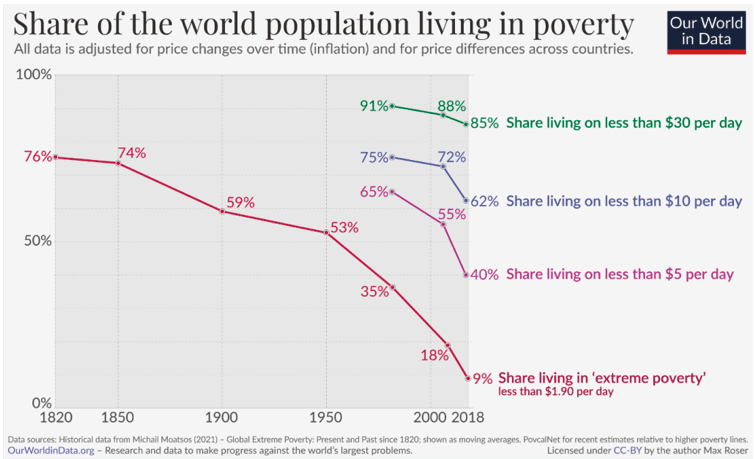

Historian Michail Moatsos produced new global dataset that goes back two centuries. According to his research three-quarters of the world lived in extreme poverty in 1820. This means they “could not afford a tiny space to live, some minimum heating capacity, and food that would not induce malnutrition.” But since then it has fallen sharply. And the share of the world population living in ‘extreme poverty’ as defined by the World Bank has never declined as rapidly as in the past three decades.

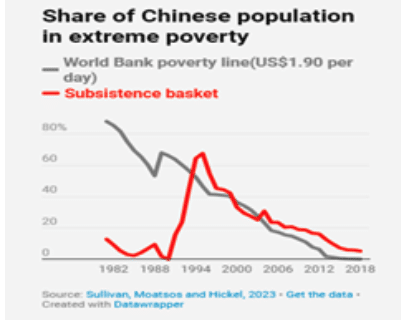

The decline in China was particularly fast.

So global poverty is nearly over? That depends on whether you accept the World Bank’s IPL. The content of the IPL is dubious to say the least. Unlike many national lines, it is not based on any direct assessment of the cost of essential needs. It is an absolute line, constant in value. Using this measure, it would suggest that ‘extreme poverty’ was the norm for virtually all of humanity for all of history, until the 19th century, when at last colonialism and capitalism came to the rescue.

Robert Allen has questioned this conclusion. He shows that the GDP data used by World Bank yields significant distortions when used to assess poverty. Instead, using consumption data, Allen constructs a ‘basic needs’ poverty line that’s roughly equivalent to the World Bank’s $1.90 line and calculates the share of people below it for three key regions: the U.S., UK and India. The results show that the high rates of extreme poverty in Asia are actually a modern phenomenon — “a development of the colonial era,” Allen writes: “Many factors may have been involved, but imperialism and globalization must have played leading roles.” Allen’s findings indicate that extreme poverty in 20th century Asia was significantly worse than under 13th century feudalism. Indeed, Allen finds that the $1.90/day line is lower than the level of consumption of enslaved people in the U.S. in the 19th century. In other words, the poverty threshold the World Bank uses, and which underpins the ‘progress’ narrative, is below the level of enslavement.

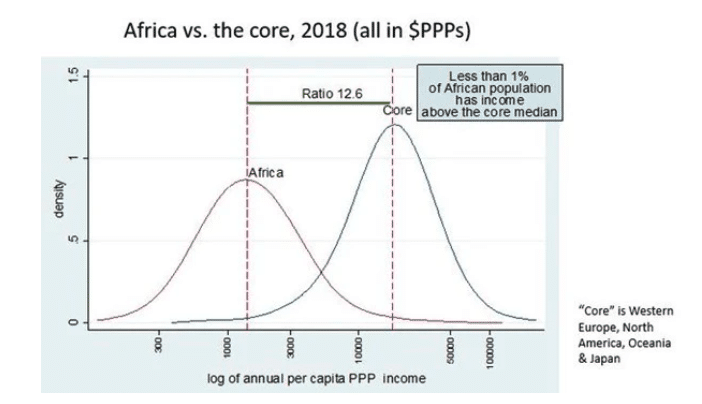

The World Bank’s IPL at $2.15 a day threshold is ridiculously low. $5 a day is what the U.S. Department of Agriculture calculates is the very minimum necessary to buy sufficient food. And that’s not taking account of other requirements for survival, such as shelter and clothing. In India, children living at $2.15 a day still have a 60% chance of being malnourished. In Niger, infants living at $2.15 have a mortality rate three times higher the global average. Less than 1% of Africa’s population has income above the Western median income.

In a 2006 paper, Peter Edward of Newcastle University used a measure that calculates that, in order to achieve normal human life expectancy of just over 70 years, people need roughly 2.7 to 3.9 times the existing World Bank poverty line. In the past, that was $5 a day. Using the World Bank’s new calculations, it’s about $7.40 a day. That delivers a figure of about 4.2 billion people live in poverty today, or up 1 billion over the past 35 years.

The large economic growth that lifted 800 million Chinese people out of extreme poverty since 1990 was a major contributor to the global decline in poverty. Peter Edward found that there were 1.139bn people getting less than $1 a day in 1993 and this fell to 1.093bn in 2001, a reduction of 85m. But China’s reduction over that period was 108m (no change in India), so all the reduction in the poverty numbers (not percentage) was due to China. Exclude China and total poverty in number was unchanged in most regions, while rising significantly in sub-Saharan Africa.

And there is another measure of poverty, the Multidimensional Poverty Index, covering 101 developing countries. This yields a poverty rate of 23% not 8%. Between 1990 and 2015, the number of people living under this line in Sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East rose by some 140 million. So the standard of living of the world’s poorest, surviving on just half the World Bank’s austere line, has only increased a small amount in 30 years. The world is not even close to ending poverty.

Indeed, let’s look at another way of measuring global poverty. Two centuries ago, the huge majority of people in Sweden lived in deep poverty. Every fourth child died, and close to 90% of the population was so very poor that they could not afford a tiny space to live, some minimum heating capacity, and food that would not induce malnutrition. Today the poverty line in Sweden is set at about $30 per day (on a PPP basis). The strong economic growth in the last century made it possible that the majority of Swedes are now living above this poverty line.

This sounds like a good measure for all the world’s people. If we rely on the $30 a day threshold as a definition for global ‘poverty’ and take into account the different price levels across countries, the latest statistics show that 85% of the world population live below this poverty line. That means 6.7 billion people.

Rather than one billion people lifted out of poverty and a global decline from 35% from 1990 to 9% in 2018 using the World Bank’s extreme poverty IPL, at $5 a day there were still 40% of the world’s population in poverty; at $10 a day it was 62% and at $30 it was 85%. In all countries a significant share of people live in poverty. Even in the world’s richest countries, a substantial share of people—between every 10th and every 5th person—lives below this poverty line. No country, not even the richest countries, has eliminated poverty. There are no ‘developed’ countries.

At a minimum the world economy needs to increase five-fold for global poverty measured at $30 a day to decline substantially. Inequality between all the world’s countries would disappear entirely in this scenario. It should therefore be seen as a calculation of the minimum necessary growth for an end of poverty.

Higher growth rates in poor countries could bring about convergence of living standards globally. The World Bank reckons that the main limitation to ending ‘extreme poverty’ is the failure of a transfer of resources from the rich countries to the poor. That means that poverty (as defined) could be ended if governments chose to do so. The World Bank explained it this way:

Suppose that the real GDP growth for the developing world as a whole is 5 percent per year. If 10 percent of this GDP growth accrued to the 21 percent of the developing world’s population who are extremely poor, and this 10 percent was distributed in a way that the growth in income of each poor person was exactly his/her distance to the World Bank Poverty Line, extreme poverty would end.

But there is little sign that the neo-colonial economies still under the boot of imperialism have any hope of closing the income gap with the imperialist bloc. Currently, international development assistance is a little over $100 billion a year. This is just five times more than the bonus Goldman Sachs staff paid themselves during one crisis year and more than five times less the annual income flows out of the poor countries to the rich. According to UNCTAD, net resource transfers from developing to developed countries have averaged $700bn a year, even after taking into account foreign aid assistance. So far from resources being transferred from the rich to the poorer countries to reduce global poverty, the opposite is the case.

UN rapporteur Philip Alston concluded his report to the UN on global poverty by pointing out that “using historic growth rates and excluding any negative effects of climate change (an impossible scenario), it would take 100 years to eradicate poverty under the World Bank’s line and 200 years under a $5 a day line (Agenda 2230!). This would also require a 15- or 173-fold increase in global GDP respectively.” The poor will always be with us under capitalism.