Black and Hispanic people in New York state prisons have a much higher chance to be denied parole than whites over the past three years–a divide that’s gotten worse since being highlighted in 2016, a new study shows.

New York’s Parole Board released 34.79% of people of color while letting out 48.71% of white people from January through June 2024, based on a report by New York University School of Law’s Center for Race, Inequality & the Law posted online Monday.

Since Gov. Kathy Hochul took office in 2021, there would be 1,338 fewer Blacks and Hispanics behind bars if they were paroled at the same rate as whites, the report shows.

“The sad reality, as this report shows, is that New York’s Parole Board is going backwards,” said the report’s co-author, Jason Williamson, executive director of NYU Law’s Center.

New York Times brought the racial disparity to light in 2016 when it reported “that fewer than one in six Black or Hispanic men was released at his first hearing, compared with one in four white men.”

As a result, then-Gov. Andrew Cuomo announced that he would nominate several minority candidates to the parole board. At the time, the board’s 13 members only included one Black man and no latinos.

Currently, the 16-member board is composed of six Blacks, three Hispanics, one Asian, one Egyptian, and five whites.

But the racial inequality problem has only gotten worse, the data shows.

From 2016 to 2021, 33.45% of people of color appearing before the Parole Board were approved for release, according to the report. By contrast, 40.39% of white people were let out by the board over that same period, the report said.

Additionally, from 2022 to 2024, the Parole Board was 32.28% less likely to release a person of color than a white person.

“This level of racial disparity in the last three years is 71.65% worse than the already existing racial disparities of the previous six years,” the report said.

Asked about the report, the state prison system’s chief spokesperson, Thomas Mailey, detailed how parole commissioners are appointed by the governor and the standards they rely upon to base their decisions. He also noted the board is the most diverse it has ever been.

But Mailey refused to specifically discuss the NYU Law’s Center’s racial bias findings.

‘I Changed But the Crime Can Never Change’

The report’s calculations include first parole hearings after incarcerated people initially become eligible upon the completion of their minimum sentences. The data also includes subsequent parole appearances typically scheduled every two years.

One Black parolee, who served just over 26 years for a kidnapping and manslaughter case where an abusive spouse was the victim, said she believes she would have been released sooner if she was white.

“The commissioner reviewing my case was white,” said Deb, who asked that her last name be withheld.

I’m Black. I’ve seen the data in this report and I have the lived experience and I have no doubt racial bias played a role in my denials.

All told, she was denied parole three times before she was let out in May via the Domestic Violence Survivors Act. The law passed in 2019 allowed for resentencing of some victims of abuse.

“I made a bad choice that landed me in prison, but I wasn’t a bad person,” Deb said.

I did everything I could in prison to heal, to mature and get my life on track.

Behind bars, she obtained a master’s degree and her release was backed by a prison superintendent each time she went up for parole.

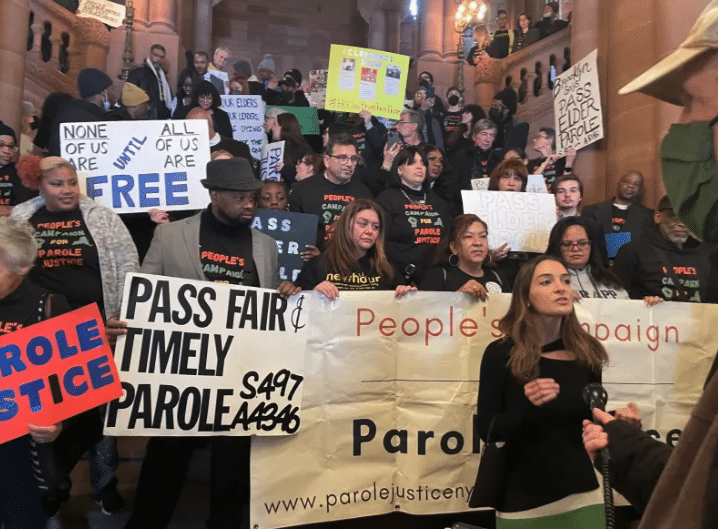

A rally to urge state lawmakers to support legislation to revamp the state’s parole system. November 8, 2024 (Photo: Jared Chausow)

Parole commissioners are supposed to use an assessment system known as Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions, or COMPAS. It uses close to two-dozen categories like “criminal personality,” “social isolation,” “substance abuse” and “residence/stability” to rank each person.

In 2016, however, ProPublica reported that the COMPAS assessment system used in Broward County, Florida was biased against Black and Hispanic inmates .

But in New York commissioners can also ignore the COMPAS score when it predicts a low chance of the person committing another serious crime. Instead, they can cite other factors, like the severity of the crime committed.

That’s exactly what happened with Deb before she was released.

“The risk assessment they used found me safe to release,” she said.

But still the Parole Board denied me again and again. With every denial, the Board cited the nature of the crime, the nature of the crime, the nature of the crime.

“I had changed but the crime can never change,” she added.

So what’s the point of going back to the Parole Board?

Retooling the System

Criminal justice reform advocates contend New York must revamp its parole system.

“The purpose of our parole release system is supposed to be to evaluate a person’s readiness for release, not to perpetuate punishment,” said state Senator Julia Salazar, chair of the New York Senate Crime Victims, Crime and Correction Committee.

Parole determinations should be based on who a person is today and what they have done to transform.

Salazar is the lead sponsor of proposed legislation known as the Fair and Timely Parole Act. The measure would restore the Parole Board to its original purpose of granting or denying release based on a person’s readiness to return to the community and current risk to public safety, rather than solely or primarily on the nature of their conviction.

Advocates have also tried since 2018 to persuade state lawmakers to pass a measure known as Elder Parole.

The idea is to automatically make anyone 55 or older who has served at least 15 years in prison eligible for a parole hearing.

Some state lawmakers who are against it, including state Assemblymember Jeffery Dinowitz (D-The Bronx), have said they are worried the measure would set free serious, unreformed criminals.

Supporters of the legislation point out that the incarcerated people would still need to be approved by a parole board, which is unlikely to release people convicted of multiple killings or other high-profile crimes–or if the person shows no signs of remorse and rehabilitation.

State Assemblymember Michaelle Solages, (D-Elmont) chair of the NYS Black, Puerto Rican, Hispanic and Asian Legislative Caucus, urged other lawmakers to support the parole reform measures.

“The data is clear,” she said.

Black and Brown families across the state are disproportionately harmed by every facet of mass incarceration, including the parole release system, and that makes our communities less safe and healthy, not more.

Reuven Bleu is a reporter for THE CITY, with a special focus on criminal justice and the city’s prison system.