ROAPE’s Peter Dwyer interviews the South African socialist David Hemson. Hemson was a leading labour militant and trade unionist during the mass working class uprising and strikes in Durban in 1973. In this introduction to the videoed interviews, Peter Dwyer discusses working class politics and the struggle against apartheid in South Africa, a history often forgotten or marginalised in popular accounts.

The popular history of the liberation struggle against apartheid, the last great social movement of the twentieth century, contains many incredible characters. Most popular books about the liberation struggle and transition from 1994 give little recognition to the role of, in South African parlance, ‘the masses’. Typical of the best-selling books at the time is an account by staunch African National Congress (ANC) supporter Alistair Sparks in Tomorrow is Another Country. Except for three brief references, there is little mention of the mass struggle and the independent trade unions in Nelson Mandela’s autobiography Long Walk to Freedom. Likewise, in The Anatomy of a Miracle, Patti Waldmeir presents apartheid history as a struggle between leaders and that Nelson Mandela was the main reason in ending apartheid and the transition to democracy.

Similarly, earlier public stories that we are told tell the same limited history. One event that captured the attention of the world’s media was the Soweto revolt in June 1976. The image of the 12-year-old Hector Pieterson being carried, lifeless and bloodied, in the arms of Mbuyisa Makhubo with his sister Antoinette Sithole agonisingly running alongside them became one of the most powerful pictures of modern political history. And so, the Soweto Revolt became a defining story and its often argued that it was a turning point in the liberation struggle.

But dig a little deeper, and speak to the not so well-known, and our gaze is turned from the townships and schools of Johannesburg to the workplaces and strikes in 1973 to, what some saw as the sleepy, unfashionable, backwaters of Durban on the tropical east coast.

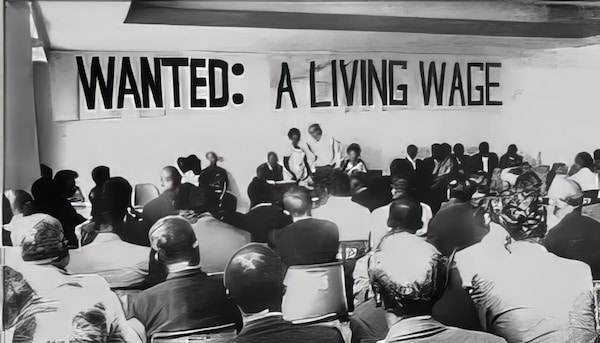

This interview is a peek inside that story and of the importance of those strikes, the incessant, sordid background to them and the daily indiscriminate police violence for being Black and ‘illegally’ in town, and the same Black people fighting for a pay rise in their newly created unions. The story is also of a small number of white students building meaningful solidarity with those Black workers. Oh yes, and the illegal inter-racial parties, but only after the political organising had ended.

This is also crucially the story of David Hemson whose life was intertwined with those whom he organised alongside and whose lives and political ideas were transformed in the process. As Hemson’s infectious retelling of those times so brilliantly demonstrates, we should never even think about disentangling the activists from the spirit of those times. The entanglement is their lives and those times. In this way Hemsons vignettes of his life enables us to see that everyone’s life embodies something of the common experience of a larger social group and shows us aspects of the experience of classes, genders and ethnicities.

Of course this is nothing new, but it is still much overlooked. Hemson’s passionate reliving of those times in this two-part interview gives rise to information qualitatively different from the lifeless data used in surveys and political science. Although individuals do not exist in a vacuum and have an umbilical connection to the social relations of which they are an active part, its important, again as Hemson points out, that we do not forget the bigger picture or get obsessed with discussing abstract forces.

And so, to the big picture.

From the election of the National Party in 1948, a form of state-led authoritarian capitalism resulted in a process of rapid capital accumulation creating a substantial Black working class that denied their basic human rights, resulting in economic and political crises igniting social conflict. The economic and political stability that had reigned since the early 1960s—after the Rivonia Trial ended in 1964 with the imprisonment of key leaders of uMkhonto we Sizwe, the recently formed armed wing of the ANC—a period often seen as a relative lull in the history of the liberation movement, was shattered in 1973 by a wave of strikes in and around the metropolitan area of Durban and what is today called KwaZulu-Natal.

The impact of Durban was brought home to me when conducting months of interviews with former trade unionists about their experiences as activists prior to joining Nelson Mandela’s first government from 1994. Years ago, as a student of the liberation movement, I’d never appreciated the importance of Durban, led, as I was by the writing on the Soweto revolt. Yet, in getting to know a slightly older generation of activists, forged in trade union activity and township politics, what surprised me was not their reverence for the Soweto revolt but the importance of the Durban strikes. It was during these conversations that one worker described to me how at the time migrant workers returning to his rural town in the Western Cape, some 1500 kilometres away, brought news to their families of the strikes that had “a ripple effect somehow” in the town and the schools.

There were those sympathetic writers such Johann Maree (1987) and G W Seidman (1994) who in hindsight dated the emergence of the all-important new independent unions from the period around the 1973 Durban strikes (unions that would go on to create the giant federation, the Congress of South African Trade Unions-Cosatu in 1985). Another Trotskyist Marxist like Hemson, Baruch Hirson, linked the rise of the independent unions to the strikes of the early 1970s, and as a precursor to the Soweto revolt in 1976. Capturing the importance of the Durban strike wave Hirson argued in 1979 that “[t]he strikes of 1973 to 1976 helped create the atmosphere of revolt and showed that the blacks were not powerless…these strikes must be seen as constituting the beginning of the Revolt, and as having affected a far wider section of the population…” (1979: 156).

A Black population that recognised the importance of and respected the new independent unions at the time. In part two of the interview, Hemson, with characteristic infectious excitement, recounts the many inspiring women in the struggle and how one, an elected shop steward called Junerose (Nala-Hartley), would walk through poor, misogynistic and at times violent townships, with thousands of pounds worth of trade union membership money. And was never once touched. To attack Junerose, was to attack the workers union. Politically, what was different at this time was that the activities of such workers and activists like Hemson, resulted in the creation of a new style of independent trade unionism outside of the Congress (ANC) Alliance sphere of influence.

Meanwhile tensions inside the ANC were reflected in the debates about how to relate to the new wave of mass action sparked by the Durban strikes in 1973 and Soweto in 1976 and the growth of independent trade unions. As debates raged inside unions over tactics and political alignment, ANC President-General Oliver Tambo, praised workers who “constitute the most powerful contingent in our struggle”. But this seemed more about trying to curry favour with a new powerful, and still politically independent, workers movement than any change in ANC tactical focus. Also, because as Hemson reveals from his ongoing research and personal experience, the ANC at the time were working with unreliable allies such as the opportunistic Mangosuthu Buthelezi.

So, back to the big picture. The expansion of the economy from the late 1940s to the late 1960s, altered the size, racial composition, and skill levels of the work force, under state-led capitalism enforced by a centralised authoritarian apartheid regime. This resulted in a diversification from dependence on agriculture and mining to manufacturing. This industrialisation process increased the economic dependence by business and the regime on African labour that, as a proportion of the total workforce, increased and gave rise to urbanisation. It provided the platform on which to build independent unions, the development of which was central to events that characterised apartheid from the 1970s onwards. And, as it would transpire, the beginning of the end of apartheid.

A complex process of organisation and agitation, by individuals and groups, both Black and white, involving workers, intellectuals and (mainly white) students like Hemson and the political ideas this process encompassed, was central to the development of the independent unions. Here the politics and ideas of Marxists like Hemson were important. Seeking social and economic justice for Black people, influenced by Marxist ideas (not aligned to ‘Soviet Marxism’ and independent of the Communist Party) they pressed for a practical stress on the exclusive role of the working class at the point of production in the struggle for liberation and for political independence from the ANC or other political parties. Debates over which Hemson and some of his comrades would later be expelled from the ANC.

Of course, activists like Hemson did not, and could not, see where this process would go, but he hints at a different political and strategic approach, one that would be central to his later political work. What is significant about Durban and other strikes in this period is that together with the new methods of organising they indicated an increasing willingness on the part of the workers to become more involved in the emergent unions and draw different political conclusions. Hemson reveals how everything was wide open politically at the time.

Before the African nationalist versions of history were written and globally popularised and mythologised, these were the days before the nationalist politics of the ANC took over the leadership of the broader liberation struggle skilfully steering it towards a reconciliation with business without fundamentally challenging capitalist power relations.

Hemson believes that late night discussions at the time with some of the best worker militants about the need for an independent worker’s party showed the potential to steer the re-emerging liberation struggle towards an anti-capitalist South Africa. This was not to be. The lesson for him, and us, is to seize political opportunities when they arise. Because they may not come round again. Hemson provides us with an indispensable, militant history of working-class South Africa, which contained so many possibilities for liberation.

Peter Dwyer is an editor of ROAPE, and member of ROAPE’s Editorial Working Group. A life-long trade unionist, he moved to South Africa in 2003 where he lived and worked in Durban, he now teaches on leadership in the National Health Service in the UK.