Donald Trump’s second presidential term has been underway for almost two months now, and every day brings headlines testifying to his determination to fulfil his promise of mass deportation of immigrants. Senate Republicans are moving forward with a bill allocating an additional $175 billion towards border militarization efforts—including deportations and border-wall construction.

Deportees have been shipped to remote camps and militarized hotels in Panama and Costa Rica, facing horrifically unsanitary, overcrowded conditions, and denied access to aid, lawyers and press. Venezuelan deportees detained at Guantánamo Bay—who have since been deported to Venezuela via Honduras—had been similarly mistreated by U.S. immigration officials.

All of this, of course, comes after four years of U.S. media and political classes working in lock-step to manufacture consent for such a catastrophic displacement event (FAIR.org, 8/31/23, 5/24/21). Both conservative and centrist media outlets associated immigrants with drugs, crime and human waste. During her bid for president, Vice President Kamala Harris supported hardening our borders, calling Trump’s border wall—which she once called a “medieval vanity project“—a “good idea.”

We’ve been here before many, many times. As they say, history doesn’t repeat itself— but it often rhymes.

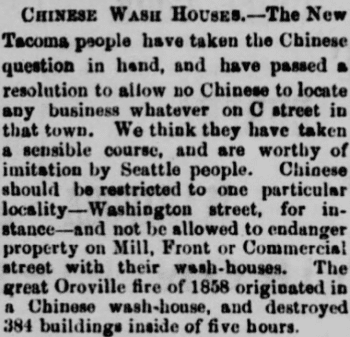

The Seattle Daily Intelligencer (12/18/1877) argued that “Chinese should be restricted to one particular locality” so as not to “endanger” white property.

Media of all kinds—from tabloids to legacy outlets—have repeatedly sensationalized the immigrant “other,” constructing an all-encompassing threat to native-born U.S. labor and culture that can always be neutralized through a targeted act of mass displacement or incarceration. The resulting violence addresses none of the structural problems that cause the immiseration of angry workers in the first place.

From Chinese exclusion to Japanese internment to Operation Wetback, this characterization of the foreigner has had catastrophic consequences for millions of human lives.

‘The Chinese question in hand’

Chinese labor began to cement itself by the 1850s as a crucial element of westward expansion. American companies employed a steady trickle of cheap immigrant labor to extract precious minerals, construct railroads and perform agricultural work. For their willingness to work long hours for low wages in dangerous conditions, Chinese workers were scorned by their fellow workers—including minority workers—helped along by an unforgiving and vitriolic media ecosystem.

Juan González and Joseph Torres’ News for All the People: The Epic Story of Race and the American Media (Verso, 2011) documents how sensationalistic media coverage of Chinese immigrant workers contributed to creating the social-political conditions necessary for the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

In 1852, prominent broadsheet Daily Alta California argued that Chinese people should be classified as nonwhite, a decision eventually cemented a year later in a murder trial that rendered Chinese testimony against white defendants inadmissible, under racist rules of evidence that also targeted Black, Indigenous and mixed-race witnesses. Sinophobic violence against Chinese mine workers from whites, Native Americans and Mexicans subsequently became much more commonplace.

Meanwhile, instead of condemning the xenophobic violence faced by these workers, Bayard Taylor at the pro-labor, progressive-leaning New York Tribune (9/29/1854) called the Chinese “uncivilized, unclean and filthy beyond conception,” and described them as lacking the “virtues of honesty, integrity [and] good-faith.”

Into the 1870s and ’80s, “The Chinese Must Go” became a rallying cry of California’s labor movement. A San Francisco Chronicle piece (7/21/1878) from 1878 described a “Mongolian octopus” growing to engulf the coast. Headline after headline described Chinese-Americans as “Mongolian hordes” and “thieves.”

Simultaneously, violent incidents targeting Chinese mineworkers became massive union-led anti-Chinese pogroms. Jean Pfaelzer’s Driven Out: The Forgotten War Against Chinese Americans (University of California Press, 2008) specifically details a late October 1871 pogrom in Los Angeles during which more than a dozen Chinese men and women were killed, with numerous Chinese homes looted for tens of thousands of dollars. At trial, members of the crowd testified to the jury that “Los Angeles Star reporter H.M. Mitchell had urged them to hang all the Chinese.”

Lynchings and pogroms were often accompanied by expulsions. In her The Chinese Must Go (Harvard University Press, 2018), Beth Lew-Williams details how Chinese laborer Hing Kee’s December 1877 murder was immediately followed by a driving-out of the two dozen other Chinese workers in Port Madison, Washington. Hing’s murder was reported by the Seattle Daily Intelligencer (12/18/1877) as merely an act of personal violence. Yet, in a different story on the same page, readers were encouraged to take the “Chinese question in hand” in a call to action to “restrict” Chinese workers from “endanger[ing]” white property by opening businesses outside of small ghettoized communities.

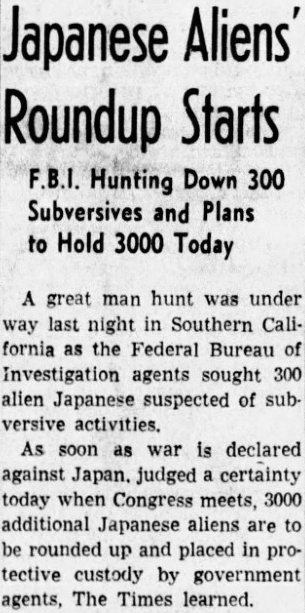

The Los Angeles Times (12/8/1941) announced the “hunting down” of Japanese “subversives.”

Finally, in 1882, the mania reached its boiling point. The populist groundswell, bolstered by media sensationalism, culminated in the passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act—the first major immigration restriction passed in U.S. history and, for a very long time, the only one that specifically named a group for exclusion.

But the U.S. economy still depended on cheap immigrant labor. Media had successfully diverted labor’s attention from the underlying systems that necessitated low-wage agricultural work—but without such a precarious class, who would take on such a thankless job?

Undisclosed numbers of ‘suspicious aliens’

As the Japanese took on the role of an exploitable immigrant labor class, similar nativist sentiment burgeoned, demanding an amendment to the Chinese Exclusion Act. After 1900, the Japanese had replaced the Chinese as the most sensationalized immigrant labor pool in California—while still making up a tiny proportion of the state’s total workforce.

Not White Enough, by Lawrence Goldstone (University Press of Kansas, 2023), catalogues the role that media outlets, among other political actors, played in setting the stage for Japanese internment during World War II. Into the late 1910s, politically ambitious media tycoon William Randolph Hearst ran headline after headline in the San Francisco Examiner warning of a Japanese invasion, and accusing Japanese workers of being disguised soldiers smuggling ammunition.

In the 1930s, as the Japanese empire expanded throughout Asia and the Pacific, anti-Japanese sentiment in the U.S. grew with it. The FBI created watch lists of potential Japanese-American subversives, including Shinto and Buddhist priests, and the heads of Japanese-American culture and language associations.

In the early 1940s, Texas Rep. Martin Dies, chair of the House Committee on Un-American Activities, regularly leaked updates to journalists of baseless “findings” of Japanese-American subversion. In a July 1941 report, the committee declared it had found that “no Japanese can ever be loyal to any other nation other than Japan,” and that even generationally U.S.-born Japanese-Americans “cannot become thoroughly Americanized.”

What Dies failed to mention was that every agent on the West Coast discovered to hold loyalty to Imperial Japan was white.

The rare examples of sympathetic coverage of Japanese Americans in local papers in San Francisco and Los Angeles evaporated after Japan’s December 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor. As the FBI and ONI began rounding up the thousands of Japanese immigrants placed on watchlists, the Los Angeles Times (12/8/1941) ran a front-page story announcing the apprehension of hundreds of “suspicious” Japanese “subversives.” On the same morning, the San Francisco Examiner (12/8/1941) described these unlawful detentions as “taking into custody undisclosed numbers of ‘suspicious aliens,’ considered as potential saboteurs.”

Media clamored in a race to the bottom to produce the most provocative anti-Japanese headlines. While supportively covering raids on Japanese-American communities, they also published piece after piece detailing Japanese attacks on U.S. soil and Japanese-American infiltrations that never occurred. In one particularly egregious instance, the Alabama Journal (12/8/1941) ran a piece headlined “How Jap Could Easily Poison City’s Water Supply.”

Though detentions began with the December 1941 round-ups, Roosevelt officially passed Executive Order 9066 in February 1942.

As shameless as the fabrications that led to and justified internment was media’s coverage of internment itself: FAIR has previously reported on the New York Times’ 1942 coverage (3/24/1942) of the concentration camps, describing the “trek” to a “new reception center rising as if by magic” as characterized by a “spirit of adventure.”

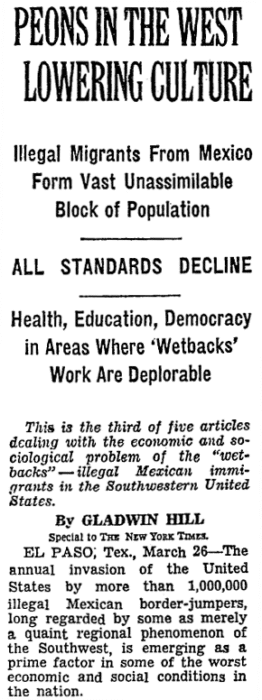

The New York Times (3/26/1951) warned that “‘wetbacks’ filter into every occupation from culinary work to the building trades” and promised that “tomorrow’s article will discuss how the ‘wetback’ influx creates an atmosphere of amorality.”

The role of media in demonizing Japanese Americans, ultimately resulting in internment, is undeniable. Newspapers worked dually as mouthpieces for unfounded FBI claims of subversion and as launching-pads for fantasies generated to maximize outrage at the perceived Japanese “other.” Then, once the “other” was contained, media went to work framing internment as a privilege.

Never mind that Japanese Americans produced 40% of agricultural output in California, that they had lived in and contributed to their communities for decades at this point— they were all double-agents, and they were neutralized.

A perfunctory disguise

Though undocumented Mexican labor had always been an instrumental part of agricultural production, especially in the U.S. Southwest, it hadn’t actually garnered large-scale attention until the 1950s; even, in fact, with a mass-deportation event during the Great Depression. But just a few short years after the internment camps closed, the U.S. undertook the high-profile mass deportation of Mexican laborers in Operation Wetback.

During World War II, with a shortage of agricultural workers, the United States came to an agreement with Mexico known as the Bracero Program. In exchange for tightening border security and returning undocumented immigrants to Mexico (on Mexico’s demands), the U.S. would receive Mexican agricultural contract workers. On paper, the deal was a win/win for the U.S. and Mexico: The U.S. would receive workers, and Mexico would stop hemorrhaging its working population.

In practice, however, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS, the predecessor of ICE) acted on the interests of big agriculture. The INS selectively enforced border security: It was common for INS to hold off on carrying out deportation orders until after the growing season. Farmers also preferred using undocumented labor to braceros, as undocumented workers could be acquired with less red tape and, usually, lower wages. Thus the INS worked specifically to uphold the precarity of Mexican labor, rather than to restrict its numbers.

Then undocumented Mexican labor became the center of a bizarre red-scare media sensation. Avi Aster (Unauthorized Immigration, Securitization and the Making of Operation Wetback; Latino Studies, 2009) pieces together the peculiar relationship between red-baiting and illegal immigration, and how it would ultimately lead to popular consent for Operation Wetback.

It began with a New York Times five-part story (3/25—29/1951) published in March 1951, detailing “the economic and sociological problem of the ‘wetbacks’—illegal Mexican immigrants in the Southwestern United States.” Times journalist Gladwin Hill took a dual interest in the horrible conditions under which Mexican migrant workers toiled, and in the imagined threat that these workers posed to U.S. society. He also insisted that it was possible for Communist spies to cross the Rio Grande with Mexican migrant workers—that although it had never happened before, “in cold fact Joseph Stalin might adopt a perfunctory disguise and walk into the country this way.”

The media and political classes ran with these claims and never looked back. In 1954, the Times ran such headlines as “’Invasion’ of Aliens Is Declared a Peril” (2/8/1954) and “Reds Slip Into U.S., Congress Warned” (2/10/1954), while the Los Angeles Times (2/10/1954) announced a “Heavy Influx of Reds Into U.S. Reported.” These marked a shift in rhetoric from warning about supposed Communist infiltrators amongst Mexicans to warning about Mexicans themselves.

In June 1954, Operation Wetback was put into effect. Hundreds of thousands were deported in the first year of the program, in a partnership between the U.S. and Mexico. What was once a fringe issue for nativist labor leaders in the Southwest became celebrated policy. A day short of the one-year anniversary of the operation, the Los Angeles Times (6/17/1955) declared, “Problem solved: For the first time in the controversial history of the wetback problem, there is hardly any problem left.”

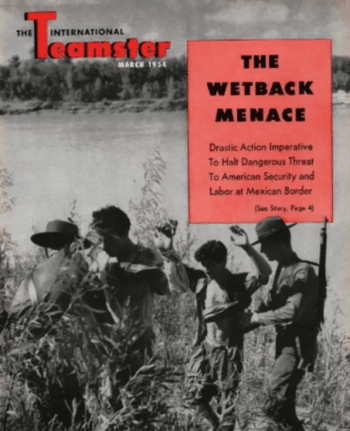

The International Teamsters (March 1954) joined in the media red-baiting, repeating the U.S. government’s absurd propaganda that “more than 100 Communists a day are coming across the sparsely patrolled border.”

Again, nothing changed for workers—rather, the state’s security apparatus bolstered its budget, labor was sufficiently distracted, and the vague specter of Communism was kept at bay for another day.

Manufacturing consent

In every case of xenophobic hysteria, media have a critical role in sensationalizing the perceived “other” and establishing the political and social circumstances necessary to justify violent acts of mass displacement and incarceration.

Though these causes are often championed by right-wing populists, sensational, nativist narratives have not been confined to right-wing media. All kinds of sources, from penny papers to union publications to legacy outlets, lie about immigrants constantly and with reckless abandon. If media aren’t lying to sell more papers and accommodate the political ambitions or xenophobic tendencies of their financiers, they’re parroting the lies of the political class.

Whether framing them as an amorphous security hazard or merely as a danger to “native” labor, media are happy to play into the scapegoating of individual immigrant groups, leading to acts of mass violence, because, ultimately, nothing changes for labor.

“Native” labor champions the anti-immigrant cause, but ultimately, our capitalist system demands that when one low-wage immigrant group disappears, another must take its place. Our economy, especially in an increasingly globalized labor market, is built around the input of low-wage immigrant labor (particularly in the agricultural sector).

As long as organized labor scapegoats the perceived “other,” and as long as solidarity doesn’t develop between “native” and “foreign” labor, all workers are worse-off. This is the social and political ecosystem that corporate media work to maintain.

Better media are possible

Independent outlet Capital & Main (3/11/25) reported on conditions in immigration detention facilities: “A few who had spent time in state prison before being transferred to ICE custody said they received much better treatment in prison than in ICE custody.”

Responsible, ethical journalism would challenge rather than parrot false claims about immigrant and migrant workers promoted by the U.S. political class—and not just when they’re at their most egregious, as when the right claimed Haitian immigrants were eating pets in Ohio. Journalists should seek to examine the differences in treatment of foreign-born and native-born labor, run human interest stories, and highlight the violence and human catastrophe involved in mass displacement and incarceration, instead of downplaying them or running stories about how these events are an “adventure.”

And instead of advancing scare-mongering narratives about how immigrant workers pose a threat to native-born labor, journalists ought to be investigating who stands to gain from pitting the TV-watching and newspaper-reading public against an easy outgroup. However, as long as corporate media exist to advance the interests of wealthy financiers and the political class, the solution lies beyond individual journalists working towards reform within their institutions.

It’s important to note that as long as nativist mainstream media narratives have existed, they’ve faced alternative media resistance, especially from within targeted communities. Prior to Chinese exclusion, for example, Chinese-American advocate Wong Chin Foo established the Chinese American, a weekly Chinese-language paper that he used as a platform to organize the first Chinese-American voters association. During internment, Japanese-Americans published papers such as the Topaz Times to promote internal education about community-led schooling, recreation and other initiatives, as well as updates about relocation.

Today, there are journalists working outside the corporate media who are producing good, humane, hard-hitting coverage of immigration. Small independent outlets like the Border Chronicle, Documented and Capital & Main offer on-the-ground news that centers people rather than national security and xenophobia.

And the democratization of alternative media channels has also allowed for mass direct resistance to immigration authorities—much to the chagrin of border czar Tom Homan, for instance, who on CNN (1/27/25) frustratedly described sanctuary city residents as “making it very difficult to arrest the criminals” because of mass education. One outlet doing this work is NYC ICE Watch—an activist group that follows in copwatch tradition by using their Spanish/English bilingual Instagram account as a platform to provide real-time updates on ICE activity and raids, organize community training and call for mutual aid requests around New York City.

Beyond the grassroots level, Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson is using a different approach, utilizing public Chicago Transit Authority adspace to promote public education in a partnership with the Resurrection Project, National Immigrant Justice Center, and the Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights on the Know Your Rights ad campaign.

In the absence of a corporate media ecosystem willing to lend its platform to this kind of work, independent media are more important than ever in resisting the ostentatious barbarism of the Trump administration’s immigration policy.

As long as establishment outlets derive material benefits from collaborating with the political and capital classes, cruelty towards the “other” can never truly be a mistake to be learned from: It’s merely a means to an end, another performance seeking to prevent U.S.-born workers from developing consciousness of all that they have to gain by standing with their immigrant counterparts.