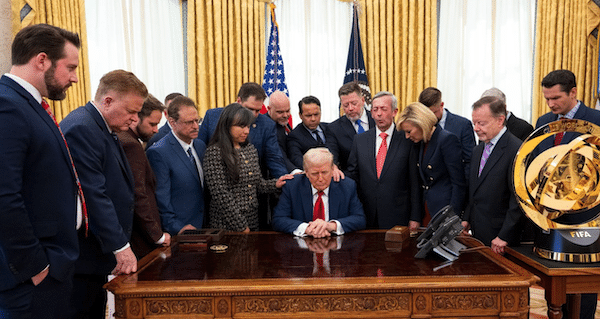

On February 7, President Donald Trump signed an executive order to establish a White House “Faith Office,” citing the necessity of “combatting anti-Semitic, anti-Christian, and additional forms of anti-religious bias” as part of the administration’s aim to “end the anti-Christian weaponization of government.” To lead the initiative, he has selected Paula White-Cain, a televangelist known for her use of prosperity gospel who recently received national attention for allegedly promising “supernatural blessings” in exchange for a $1,000 donation.

“While I’m in the White House, we will protect Christians in our schools, in our military, in our government, in our workplaces, hospitals, and in our public squares,” he said while announcing the new task force alongside U.S. Attorney General Pam Bondi at the annual National Prayer Breakfast in February.

And we will bring our country back together as one nation under God.

The Faith Office marks the latest in a series of moves by Trump that cater to his large voter base of Christian nationalists—those who believe that the U.S. government should actively promote Christian faith as a core part of American identity. Groups like the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty (BJC) argue that in the current political climate, Christian nationalism functions as a cultural framework that incorporates elements of white ethnonationalism alongside nativist, patriarchal, militaristic, and authoritarian views. By weaponizing Christian texts and symbols to enforce the idea that women, people of color, and queer and trans people are second-class citizens, some experts say, Christian nationalists actively push an “us versus them” worldview.

“[Christian Nationalism has] less to do with Christianity or the teachings of Jesus and [is] more about this ethnonational identity of whiteness,” says Amanda Tyler, executive director of the BJC and lead organizer of its Christians Against Christian Nationalism campaign.

That is really important to understand and distinguish Christian nationalism from Christianity as a 2,000-year-old religion based on the scriptures telling about the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus.

Since Trump’s Inauguration, explicit appeals to conservative Christian rhetoric—and, in particular, against marginalized groups—have appeared in his approach to national policy. In an Executive Order asserting that U.S. policy would “recognize two sexes, male and female,” Trump declared that newly issued U.S. passports would no longer list preferred gender status for trans and nonbinary people, after which White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt clarified that “they can still apply to renew their passport—they just have to use their God-given sex, which was decided at birth.” While some religious groups have criticized Trump for supporting access to in vitro fertilization treatment and previously expressing doubts about Florida’s six-week abortion ban, his administration has cut tens of millions in federal funding for Planned Parenthood and promoted the conservative Christian view that life begins at conception.

He has also led a campaign of mass deportations that has included allowing U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to conduct raids in churches; Tom Homan, Trump’s “border czar,” has publicly espoused racist immigration conspiracy theories, and reportedly met with associates of a white supremacist group loosely associated with a Christian nationalist “unwoke” church on at least four separate occasions. The establishment of the Faith Office only further signals Trump’s alignment with this movement.

“I think a faith office does not belong in the White House or any federal cabinet or building,” says Freedom From Religion Foundation co-president Annie Laurie Gaylor.

There should be no bias against anybody based on religion, not just Christians. And this shows the presumption that we are a Christian nation, or that Christians are first-class citizens and the rest of us don’t count as much.

Secular governance advocates have also argued that Trump’s embrace of Christian nationalism is a threat to the separation of church and state, and American democratic norms more generally. “Christian nationalism is an acute and immediate threat to democracy, and has become a vector for democratic backsliding in the United States and other parts of the world,” says Drew J. Strait, PhD, Associate Professor at Anabaptist Mennonite Biblical Seminary and author of Strange Worship: Six Steps for Challenging Christian Nationalism.

This vision of authoritarian reactionary gospel is very much incompatible with democratic pluralism because it wants to value and give pride of place and privilege to Christians and deny some of those same privileges to their neighbors, whether it’s a Muslim neighbor, an atheist, and so forth.

Many agree that to prevent the expansion of Christian nationalist influence from the ground up, communities must raise awareness, and engage in community organizing to ensure the rights of their neighbors and community members, which are at risk of fading away.

“We all have a role if we’re going to keep our republic,” says Gaylor.

We [have] to speak up. We have the power to resist against what looks like a pending fascistic takeover of our government. James Madison said it is proper to take alarm at the first experiment on our liberties, and there’s been way too much experimentation going on.

“It’s easy in this really overwhelming moment with all that’s happening in Washington, for people to feel like everything is beyond their control, like they can’t do anything,” says Tyler. But in spite of this, she says,

it’s absolutely critical that people understand the power that we do have in this democracy, and that our impact and our ability to make change is actually the strongest at the local level.

With organized opposition against Christian nationalism continuing through initiatives such as the Christians Against Christian Nationalism campaign led by Tyler, Strait says that the organized opposition against Christian nationalism must include Chrisitian congregations, which play a large role in shaping the national conversation at the local level. “At the core of this is a Christian problem,” he says.

[While] Some congregations are part of the problem, some congregations are part of the solution, and the latter we don’t talk about enough. Churches are getting more and more organized, and I would say we are still at the stage of creating an ecumenical coalition of churches doing this work.

Isabel Rodriguez is an editorial intern at The Progressive. Isabel is a graduate student studying Public Diplomacy at the University of Southern California and a University of California, Berkeley graduate.