Over the past year and half, I have received dozens and dozens of text messages from private developers inquiring about the land my grandparents owned before their deaths. Most of the messages begin the same way: a quick greeting followed by some variation of “Did you know you own a vacant lot? We have a proposal to take it off your hands!” I normally respond with a swift “no,” but on one or two occasions I entertain the anonymous and hopeful purchasers by asking how much they’re offering. I’ve done my research, and right now land in this area is selling for anywhere from $8,000—$30,000 per acre. I’ve never been offered more than $5,000 per acre during one of these interactions.

Thankfully, I’m no amateur, and my grandparents prepared me for moments like these. They spoke often of how predatory developers can be and how they devalue our land only to turn around and make millions off of it. Developers are only one prong of this sharpened pitchfork, they taught me, and there are countless other people and entities looking to push Black people off of the land we’ve fought for, sometimes with our lives. My grandfather in particular guided me to be proud as a sixth-generation Black landowner and to be vigilant of all who want to ensure I’m the last generation to make such a claim. In the twenty-first century, Black Americans own less than 1 percent of U.S. farmland. This alarming statistic is part of a larger, intergenerational legacy of land theft, and I know from conversations with my grandparents that our job is to remember and tap into our ancestral legacy of resilience. To never let go of what those before me had fought so hard for.

My grandmother, Jenail, was born to a family of Black sharecroppers in Candor, North Carolina, where segregation ruled much of her early life. Her family’s white landowner and employer controlled what they ate, where and how they lived, and the rate at which they’d be paid. Growing up, Grandma didn’t talk much about her childhood; I sensed it was a tender and painful memory for her. But as an adult, my research and writing forced me to ask more questions. As a young girl, Grandma never knew Black people who owned their own land—not until she met and fell in love with her future husband, Alfred.

Alfred and Jenail Baker

Jenail moved North during the Great Migration, ultimately settling in New Jersey, where she met Alfred Baker, another North Carolinian who had settled up North. Except Alfred didn’t carry the same dread of the South that Jenail did. His shoulders didn’t tighten when he journeyed home. He was freer and lighter there than anywhere else.

He still owned land in North Carolina with his parents and siblings and always wanted to return. That amazed Jenail and excited her.

Through marriage, Jenail became a landowner. The two spent most of their adult lives up North while visiting and planning for a retirement down South. During those visits, Jenail enjoyed the apple dumplings her mother-in-law made from scratch, the fresh eggs from the chickens clucking in the morning, and the water from the well they’d dug themselves. She also learned the story of the Baker land and of the life it had afforded the Baker family. Alfred’s great-grandfather bought it after emancipation from a Confederate widow, and each generation expanded those landholdings to the 600-acre Baker farm that they loved so much. After decades of systematic land loss and theft, Alfred worked fervently to buy back parcels of land they’d lost to private developers or after being unable to afford rising property taxes and predatory heirs’ property laws.

Heirs’ property has been dubbed “the leading cause of Black involuntary land loss” by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The laws dictate land left behind without a trust or formal estate plan will be communally held by those family members remaining. On the surface, heirs’ property seems like a harmless way for land to be divvied up among living descendants. But in practice, heirs’ property leaves Black landowners with little control over their property as courts opt for partitions by sale when distant family members sell their share to outsiders.

Jenail Baker sits at the author’s wedding with a photo of her deceased husband, Alfred, on a chair set aside for him.

Let’s say, for example, that a parent’s land is left behind to five children as heirs’ property owners. Each child owns an equal 20 percent share of each acre. When those five siblings have children and their children have children, the share dwindles further and further. Often, hundreds of heirs will have an equal share of land that only a few people are invested in or living on. By nature of these “cloudy” deeds, heirs’ property owners are less eligible for programs and grants that allow them to sustain land ownership like securing a USDA farm number, aid from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), or the ability to launch businesses on their land. With the land in limbo, many heirs begin to see it as more burden than blessing, and are pushed into partition sales which benefit private developers and local lawyers more than the descendants intended to receive an inheritance from their deceased loved ones.

Baker family land

Initially, my grandmother wasn’t aware of this history. Jenail looked out at the Baker family land and saw something more beautiful than what she’d known as a sharecropper. With a husband who showed her land didn’t need to be synonymous with subjugation, Jenail ran fully toward the South again. Grandma began dreaming of the South, too—of a big blue home with a wraparound porch and a lake to look out over. She dreamt of bringing her children and grandchildren and teaching them to love it without being subjected to the early experiences she had. She took up space in ways she hadn’t been able to as a little girl—and the difference was ownership.

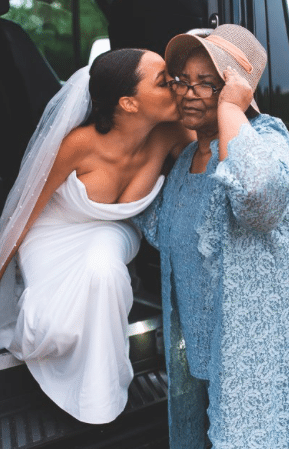

The author kisses her grandmother Jenail at her wedding, which took place on the Baker family land.

As I learned writing a book on this subject, Rooted: The American Legacy of Land Theft and the Modern Movement for Black Land Ownership, land ownership was one of the first and only paths to Black autonomy. For Black families in the South, owning the land shapes your experience on it. It’s the difference between toiling away on the land and running a business on the land. The difference between being exploited and building wealth for your loved ones. Between being a pawn and being a stakeholder. I came to learn just how much it matters by talking to my grandmother. “From working on white people’s land as a sharecropper and now white people rent the land from us,” she once told me.

After my grandmother’s death, I became hypervigilant of the ways my elders and ancestors were pushed off of their land and how children bear the brunt of reversing those dynamics.

Land transfers to younger generations can be the key to intergenerational wealth or the continuation of intergenerational battles. When policy is designed to protect only those with trusts and private lawyers, the wealthy get wealthier while the working class grows poorer. We need to get more innovative as a society to ensure that the disenfranchised and dispossessed are offered some serious relief.

Within my family, I know that the responsibility has now fallen to us: Alfred and Jenail’s children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. This past Thanksgiving, we circled around a bonfire in the backyard of the home she and my grandfather built with their life savings. We talked about what made it possible for us to be there, how to expand the home, what new structures to build, how to take care of the lake, leasing land to renewable energy companies, and so much more. We made plans for newsletters to help the family remain connected to the land, and we all agreed to ignore any inquiries about selling the land because what we have is priceless. This land has been the site of two weddings, countless funeral repasts, and dozens of other celebratory moments. Just as Jenail and Alfred intended. A legacy we will keep alive for generations to come

Brea Baker is a writer and activist whose book, Rooted: The American Legacy of Land Theft and the Modern Movement for Black Land Ownership, was published with PRH/One World Books.