One of the most eye-popping late-spring heat waves on record made its way from the Pacific Coast into the center of North America this week. Numerous towns and cities have notched their hottest days and/or warmest nights ever experienced this early in the season, and some have soared to readings unheard of anytime before June.

The warm air was drawn north from the fast-heating drylands of northern Mexico and the southwest U.S. by a powerful upper low pushing across the continent. Hollywood and vicinity got a sneak preview of the evolving heat wave last weekend before it went nationwide. Burbank, California, set records with 98°F and 101°F on Friday and Saturday, May 9 and 10. Even a mere 81°F was enough for a daily record on Saturday at the Los Angeles International Airport, where sea breezes often keep spring heat tamped down.

Intense heat feeds fast-growing wildfires from Minnesota to Manitoba

Early-spring heat waves, such as the great “warm wave” of March 2012, can feel more pleasant than problematic, even if they trigger major problems such as fruit trees blooming too early to avoid frost damage. But this week, with sunshine already at late-July levels, the burners were turned on full blast all the way from northeast Mexico into southern Canada.

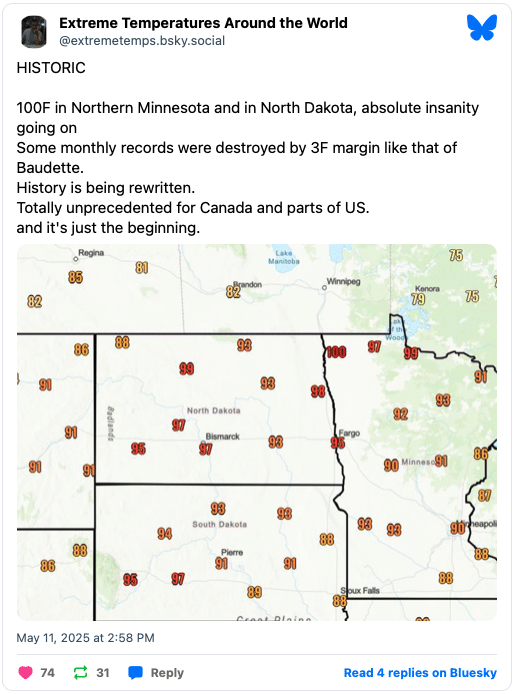

At the U.S.—Canada border, International Falls, Minnesota—the self-described “icebox of the nation”—typically sees highs and lows in mid-May of around 64°F and 38°F. On Sunday, May 11, the town hit 96°F. It was a full month earlier than any day that hot had been experienced in 127 years of recordkeeping.

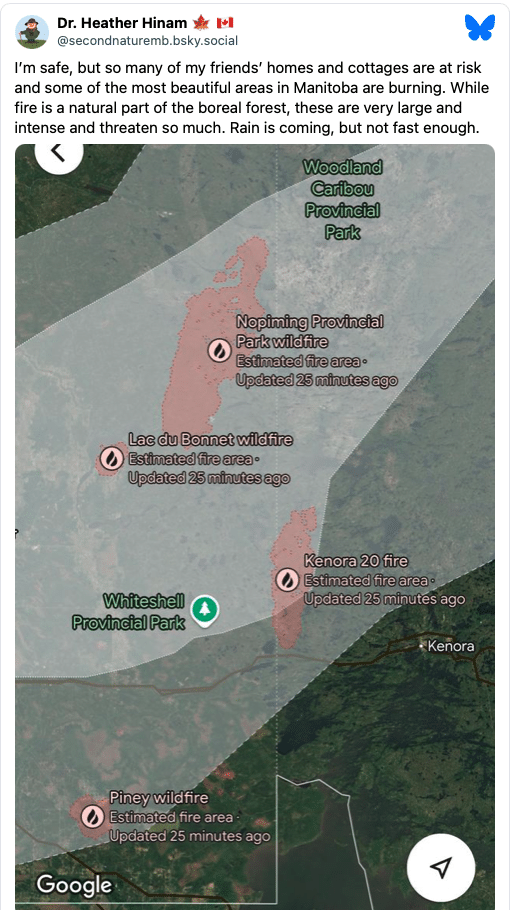

The record heat brought unusual fire weather that helped fuel three large fires north of Duluth, Minnesota. These fires were were 0% contained as of May 15, and had destroyed dozens of structures and forced evacuations of over 1,000 homes. Smoke from the fires triggered an air quality alert across northeastern Minnesota Wednesday and Thursday for an Air Quality Index (AQI) reaching Orange (unhealthy for sensitive groups).

Additional heavy smoke was being generated by large fires that had ignited in Canada to the north of Minnesota. One of these fires burned into the town of Lac du Bonnet, Manitoba, killing two people and forcing the evacuation of over 1,000, while another blaze consumed some 250,000 acres in a single day in and near Nopiming Provincial Park.

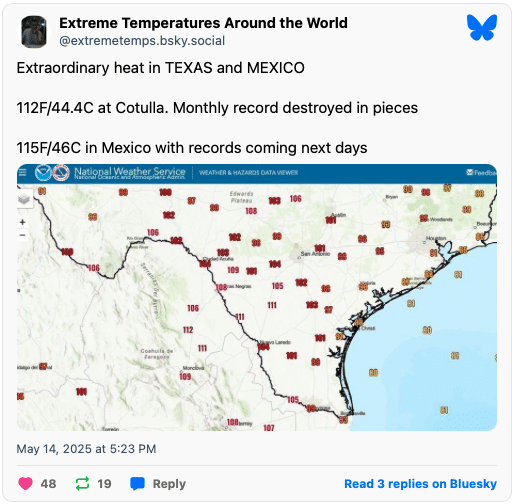

At the south end of the continent’s bifurcated heat wave, Austin, Texas, had back-to-back readings of 101°F on Tuesday and Wednesday, May 13 and 14, and San Antonio had its earliest-ever 103°F on Tuesday followed by 102°F on Wednesday. Readings above 90°F were widespread across the Great Plains in between.

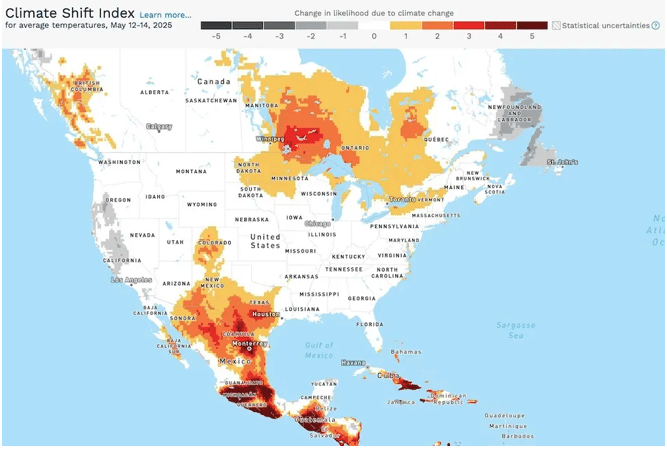

Figure 1. As assessed by Climate Central’s Climate Shift Index, the extreme heat observed in average temperatures (including highs and lows) across the three-day span of May 12-14 were made at least 50% more likely by long-term climate change (lightest tan) over most of Mexico and Central America and parts of the central U.S. and southern Canada. The extreme heat was made 2 to 4 times more likely in sections of southeast Manitoba and western Ontario as well as southern Texas, and more than 5 times more likely in much of southern Mexico. (Image credit: Climate Central)

Scorching heat extended across the Rio Grande Valley (perhaps the world’s hottest location on Wednesday) and into drought-plagued northwest Mexico. May is often the hottest month of the year in Mexico, as sunlight intensifies ahead of the cloudier summer monsoon period, but the current heat is unusually intense even for May. About half of Mexico was experiencing drought as of the end of April, the nation’s water commission reported, with extreme to exceptional drought across all of Chihuaha state, which adjoins West Texas.

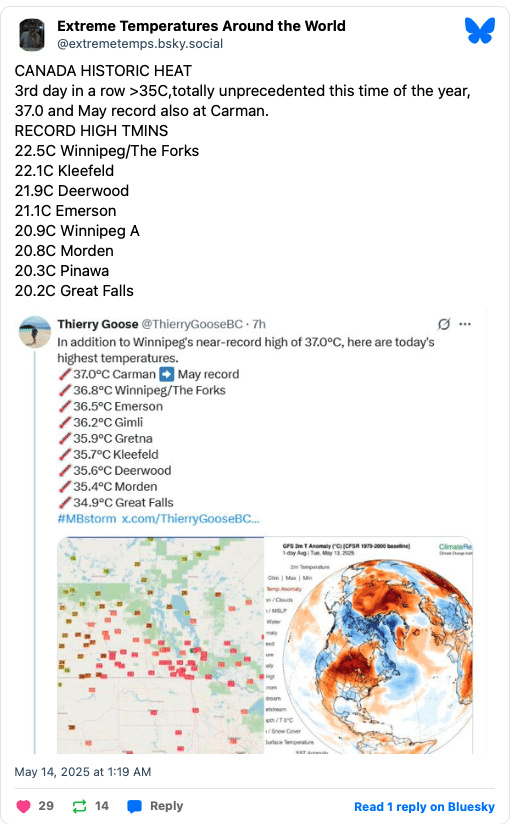

Well into Canada, the summerlike heat was accompanied by an infusion of so-called “tropical nights”—when the low temperature fails to dip below 68°F (20°C). On Monday, the low at International Falls was a mind-blowing 70°F. Only a handful of nights in the town’s century-plus history have recorded lows that warm, even in midsummer, and never before had a 70-degree low occurred before June 17. Further north, many locations across southern Manitoba saw tropical nights, and the provincial capital of Winnipeg topped 95°F (35°C) for three consecutive days.

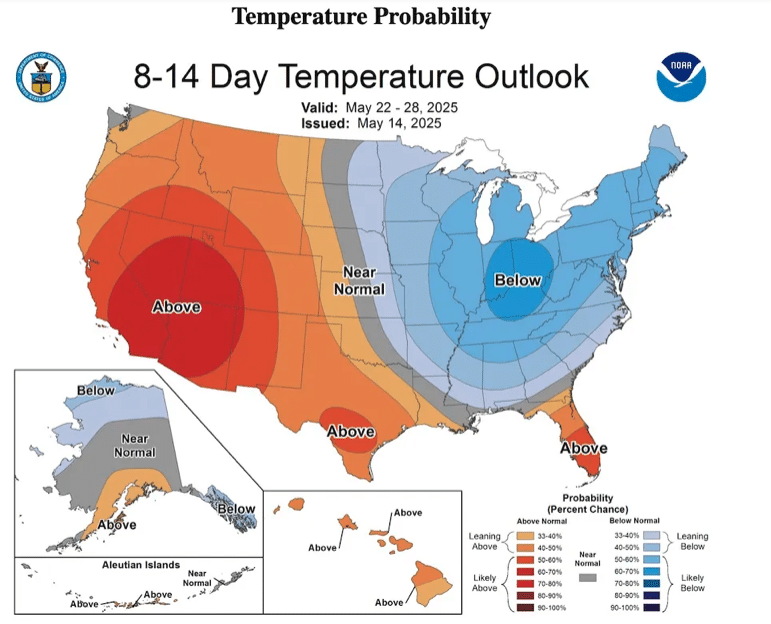

Even before this week, the 48 states of the contiguous U.S. were off to a running start for one of their hottest springs in history. The two-month span of March and April 2025 was the fifth hottest in 131 years of U.S. recordkeeping. If the latter half of May were to bring more large-scale, prolonged heat waves, it could push the full three-month spring period (March-May) above the warm-wave-goosed record-hot spring of 2012. Next week’s pattern looks notably cooler, though, especially in the eastern half of the country.

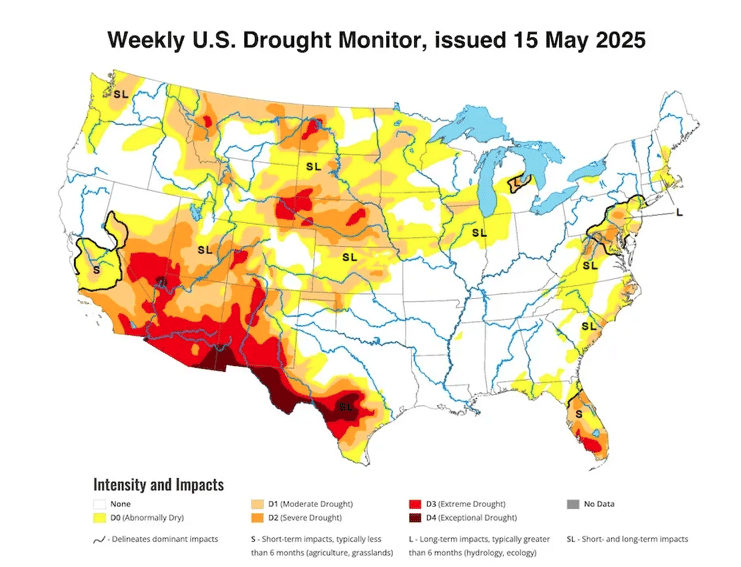

There’s also been enough moisture in many parts of the central U.S. to cut the drought risk that an intense week-long heat wave can help bring. In fact, it’s been an especially wet spring over the Ohio and Mississippi valleys, as well as part of the Southern Plains. But this month, drought has been creeping its way eastward from the Rockies into the Northern Plains and hitting extreme levels from the deserts of southern Nevada and California through southern New Mexico and Arizona into southwest Texas.

Figure 3. The U.S. Drought Monitor weekly analysis, issued on Thursday, May 15, based on data through May 13. (Image credit: National Drought Mitigation Center)

Water crisis rearing its head once more in Southwest U.S.

Conditions look increasingly grim for the crucial Lake Powell and Lake Mead reservoirs, where a brief wet period that peaked in 2023 provided only meager relief from 20-plus years of megadrought. As of late April, the reservoirs were both at only 33% of capacity, and water levels were lower in Lake Mead than at any time in modern history except for 2022-23, just before the wet-period reprieve. This year, parched soils in a warm, dry spring are absorbing much of the runoff from a slightly-below-average snowpack, so much less water than usual is expected to flow into the lakes.

“Everybody keeps hoping that the only way we’re going to really rebuild storage is if we have another ridiculous, gangbuster year like 2023… but that’s highly unlikely,” watershed scientist Jack Schmidt (Utah State University) told the Salt Lake Tribune.

Jeff Masters contributed to this post.

Bob Henson is a meteorologist and journalist based in Boulder, Colorado. He has written on weather and climate for the National Center for Atmospheric Research, Weather Underground, and many freelance venues. Bob is the author of “The Thinking Person’s Guide to Climate Change” and of “The Rough Guide to Climate Change,” a forerunner to it, and of “Weather on the Air: A History of Broadcast Meteorology”, and coauthor of the introductory textbook “Meteorology Today”. For five years and until the summer of 2020 he co-produced the Category 6 news site for Weather Underground.

In 2018 Bob began a three-year elected term on the AMS Council, the governing body of the American Meteorological Society. His interests include photography, bicycling, urban design, renewable energy, and popular culture. A native of Oklahoma City, he earned a bachelor’s degree in meteorology and psychology from Rice University and a master’s degree in journalism, with a focus on meteorology, from the University of Oklahoma.